Oldtidsbrønde

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.7146/kuml.v6i6.97289Nøgleord:

Prehistoric wells, forhistoriske brønde, Møllesø, Late Celtic, early roman, sen keltisk, tidlig romersk, jernalder, iron age, Lindholm høje, Bronze age, bronze alder, viking age, viking period, vikingetidResumé

Prehistoric Wells

The presence of drinking water has at all periods been one of the factors determining the dwelling-places of man. It would appear that, during the Stone and Bronze Ages, settlements were sited by natural springs, rivers or other surface sources. Only one well, a hollowed treetrunk, is known from the Late Bronze Age 1), and this was used as a deposition place for offerings. A circular plank-built well in East Jutland dated to the Celtic lron Age is similarly interpreted 2).

The considerable growth of population in the Early lron Age, attested both historically and archeologically, forced a spread of cultivation over new areas where, if there was no natural drinking water, it was necessary to obtain it by sinking wells. The first wells, from the PreRoman 3) and Roman 4) lron Age, about 2 metres deep, were not designed to tap artesian water but are placed in natural hollows and were probably water-filled for the greater part of the year.

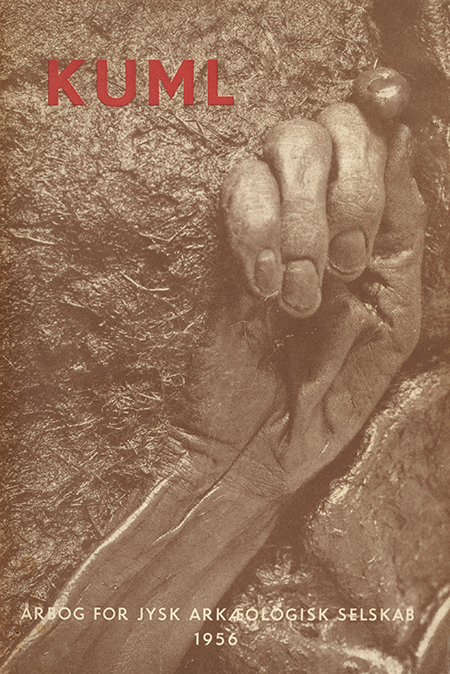

In the summer of 1955 a collection of hazel wands and potsherds were found on the bed of the lake of Møllesø, which was drained in 1760 and is now under cultivation. The discovery was made in the course of clearing a drainage channel some 3.25 metres deep. An investigation was commenced and the first to appear was a circular interlaced structure of hazel wands which proved to be the present upper edge of a wickerwork well, the original upper portion having been cut away when the drainage channel was dug. The wands were intertwined on a framework of thicker vertical hazel sticks, pointed at the lower end and standing in double and treble rows at a distance of 20-30 cms. from each other (Fig. 1). The wickerwork was up to 20 cms. in thickness and still survived to a depth of about 50 cms. The interior diameter of the well was 120 cms. and its remaining depth 93 cms, the bottom of the well being 36 cms. above sea-level. It was filled with light-coloured drift sand mixed with a quantity of potsherds and animal bones.

Other hazel wands in the channel sides proved on investigation to be the wickerwork of a second well, later than Well I, into which it had cut slightly. The side had been cut away by the drainage channel and it could therefore be excavated both in plan and in section (Figs. 2-3). It was conical in shape, 100-110 cms. in diameter at the top and 40 cms. less at the bottom. The surviving depth of the well was 145 cms., the wickerwork being about 120 cms. high, well preserved but more flimsy than that of Well I (Fig. 4). Here too the well was filled with drift sand, animal bones and potsherds. The original upper edge of neither well could be determined; their surviving upper edges were, for Well I and Well II respectively, 230 and 130 cms. below the original ground surface.

The majority of the potsherds could be reassembled (Fig. 5) and date the wells to late Celtic or early Roman lron Age. One vessel had been cracked in prehistoric times and repaired with a resin-like substance. The bones from Well I have been identified as those of goat and probably sheep, domestic pig, ox and horse, those from Well II as of a young pig.

lnvestigation showed that the method of construction of the wells must have been: first, to stick the vertical poles into the ground in a circle and to weave a wickerwork cylinder around them; and then to dig the hole in which to sink the cylinder.

A settlement site measuring about 200 X 100 metres, and covered with potsherds of the same type as those from the wells, was identified close to the wells and level with the present surface. This level gives an original depth for the wells of 3--4 metres.

*

The large-scale excavations at Lindholm Høje near Nørresundby have up to now uncovered five wells. The great cemetery of Lindholm Høje, where to date about 700 graves have been found, dates from 500 to 900 AD; after that date it was covered with drift sand and a village was built above it about 1000 AD. No wells have been found in association with this village. It had long been assmuned that the drift coverage of the cemetery was caused by breaking up by cultivation the light soil north and west of Lindholm Høje. The correctness of this theory was shown two years ago when, during the construction of a rifle range, the excavating machines found widespread traces of settlement in this area. An emergency excavation was carried out with the full personnel from the Lindholm Høje excavation.

In the course of this operation a timber-built well was found. It lay at the bottom of a shaft, about 3 metres deep and steep-sided except to the north where there presumably was access to the well. The actual well was about 100 cms. deep and square in shape with an interior measurement of about 110 cms. It was constructed of massive well-shaped timber, tongued and grooved together. In each corner stood a post which supported horizontal planks forming the sides. On the north and west sides massive planks had been laid to provide a firm standing surface. Around the well pointed planks had been driven into the earth close together to prevent quicksand from flowing into the well. The well contained many twigs and branches and a quantity of poorly preserved animal bones and teeth. At the bottom lay the sherds of a little spherical vessel with vertical knob-handles, horizontally pierced (Fig. 7) 10). Some of the timbers of the well showed holes and shapings with no present constructional significance, showing them to be reused timber.

The next well (L. H. no. 1559), also at the bottom of a shaft, was of more massive construction than the first (Fig. 8). It consisted of a massive square well-shaft of heavy shaped planks, tongued and grooved together, with a maximum interior breadth of 120 cms. The sides of the well were packed with large granite stones; the bottom, funnel-shaped and set with large stones, lay about 3.5 metres below original ground surface (Figs. 9-10). Alongside the south side of the well was a little half-oval construction of pointed planks, their maximum length 130 cms. These formed a funnel, with interior dimensions about 50 X 70 cms., of which the timbers of the well formed one side. lts base lay some 30 cms. higher than the bottom of the well, and it cannot therefore have been used as a well at the same time as the main construction. It may have served as a cooling room for milk or other foodstuffs. The stoneset well contained a number of potsherds, attributable to the Later lron Age or the Viking Period, as well as a badly preserved comb of bone ornamented with groups of oblique lines. From the little plank enclosure came a well-preserved birchwood scoop with a handle ending in a stylized animal head (Fig. 12). On it stood a cylindrical wooden box (Fig. 11). Their position suggests that they were not dropped into the compartment but placed there, a circumstance which supports the theory that the compartment was used for food storage.

After the completion of the rifle range two further shafts were found, one of which contained two square wells (L. H. no. 1833) (Figs. 13-15), with interior dimensions 100 and 160 cms. The smaller well-shaft cut into the larger, which is thereby proved to be the earlier. No ramp to the edge of the wells could be traced. The bottoms of the wells lie about 3 metres below original ground level. No artifacts apart from some unidentifiable potsherds were found in these wells.

The other shaft contained a well (L. H. no. 1832) formed of wickerwork with an inner reinforcement of closeset pointed planks (Figs. 16--17). Its interior diameter was about 100 cms. and its depth 90 cms. The sides of the shaft were not too steep to have been used for descent and ascent (Fig. 18). The well contained potsherds of Later lron Age or Viking Period type, a fragment of a wagon wheel and three fragments of a plain wooden box.

None of the wells was artesian. The terrain lies high and the subsoil consists of sand, but there is a thin clay stratum 3-4 metres down which contains the surface water and allows it, in rainy periods, to stand no more than 25 cms. below ground surface. The number of wells inside a small area indicates that a large village originally stood here, and trial trenches showed that the settlement level continued for a considerable distance. Potsherds prove its contemporaneity with the Lindholm Høje cemetery.

*

As will be seen from these notes there is not yet sufficient material to provide a basis for dating wells by their mode of construction. In particular wickerwork wells were used both in the Celtic Iron Age and in the Germanic lron Age or Viking Period. The plank-built wells may be confined, as here, to the late Germanic lron Age or the Viking period, but too little material exists for any certainty. The wells found at Trelleborg, Hedeby and other Viking sites show constructional differences from these.

Oscar Marseen

Downloads

Publiceret

Citation/Eksport

Nummer

Sektion

Licens

Fra og med årgang 2022 er artikler udgivet i Kuml med en licens fra Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Alle tidligere årgange af tidsskriftet er ikke udgivet med en licens fra Creative Commons.