The reconstruction of the stave church at Hørning

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.7146/kuml.v39i39.111969Keywords:

reconstruction, stave church, hørning, viking ageAbstract

The reconstruction of the stave church at Hørning

When Christianity won through in Denmark late in the Viking period the first churches were erected, built of wood. None actually survive as buildings, but remains of 10-15 churches have been uncovered, mostly below the floors of stone churches. Although so few have been found, it is clear that many more were built in 11th century Denmark. We read in Adam of Bremen's description of the Scandinavian countries from about 1070 that there were several hundred churches within the borders of Denmark in his day, and most of them must have been wooden. The construction of stone churches in any appreciable number seems only to have begun at the end of the 11 th century (Møller & Olsen 1961, 35). The written sources hardly tell anything of church building before 1100.

At Moesgård the Prehistoric Museum and the University of Aarhus are planning jointly to build a full-scale reconstruction of a stave church from the end of the Viking period. It will be located close to the already existing reconstructions of Viking houses at the museum.

The Danish stave church from Hørning near Randers in eastern Jutland was chosen for the project. It was excavated by the National Museum in 1960 below the floor of the present Hørning church. Its ground plan was clearly visible as a rectangular nave 6 m long and 4.5 m wide and a 3.3x33 m square chancel. Carbonized oakwood in the postholes showed that the little church had been destroyed by fire. The charred posts were so well preserved that in most cases there was reasonably accurate information on the cross-sections of the posts (fig. 1).

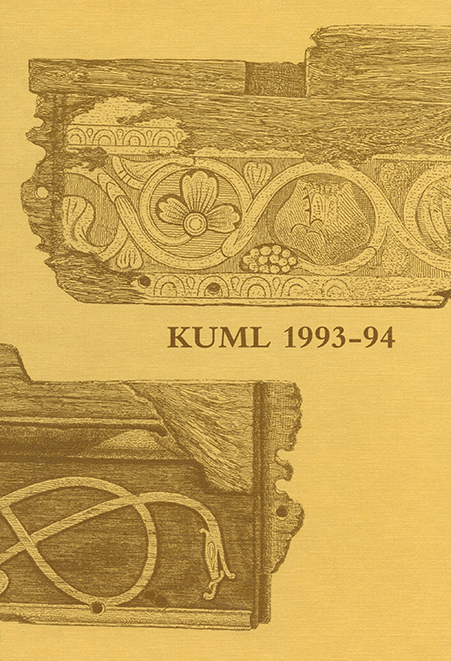

As well as the traces under the church we have the famous decorated plank from Hørning. It was found when the church was restored in 1887 and was discoveed in the fill of the choir wall (fig. 2). Traces of burning on its back make it likely that it came from the burnt wooden church. In the conflagration layer of that building there was found another small piece of wood with remains of coloration like the painting on the plank (Krogh & Voss 1961, 17). The likelihood that the plank belonged to the wooden church is further supported by tree-ring dating, which shows that it was felled in 1060-70 A.D. (Arkæologiske udgravninger i Danmark 1990, 234).

The plank had been part of the hammerbeam below the eaves into which the vertical wall planks had once slotted. On its upper edge there are traces of a notch, and at one end of the tenon with which it had been secured to a corner-post. On the bottom edge there is the large groove into which the tops of the wall planks fitted. The outer face of the hammer beam was decorated with characteristic animal slings in Urnes style, framed below by the raised edge of the plank and above by a rope moulding. Some of the original paint survives and shows the background colour to have been black, against which the Urnes beast stood out in a strong yellow, with red eyes, snout, and comb. There is also red on the raised lower edge and red and black alternate on the rope moulding. The inner face of the plank is smooth, and on it a plant tendril is painted in red, yellow, green and black on a white lime background.

The plan of the wooden church and the lucky find in the last century of the piece of hammer beam both tell us a lot about the original church, but by no means solve all problems, so that several decisions will have to be made when it is reconstructed. One of these decisions is whether to use only the building methods used at the time (so far as we know them), or to resort sometimes to modern technology. It is sure that a number of compromises will have to be made if the church is to be built and maintained without excessive expense.

Detailed projecting brings matters into focus that might not otherwise have been thought of, but that is after all the reason for undertaking the task at all. At this stage the architect realized that the fine carved animal sling had functioned rather like a decorated frieze in Classical architecture. Probably the hammer beams of the early decorated churches were commonly decorated in this way, as shown by Irish manuscript illuminations from the 700's, cf. fig. 3 (Henry 1973, colour plate B). However the best surviving representations of small, early, wooden churches are seen on the tops of the great Irish stone crosses of the Viking period (fig. 4).

The building's most important structural element was the earthfast wall posts. Together with the horizontal hammer and gable beams and the foot beams they gave rigidity in both lengthwise and transverse directions (fig. 5). One reason for the rigidity was that the parts were joined together by very wide tenons, which were themselves held by pegs.

As with the Norwegian stave churches, the nave and choir were made of equal height (Bjerknes 197, fig. 66), so the hammer beam of the choir joins on to the eastern gable beam, which is the best solution both constructionally and architecturally. As the Urnes animal interlace as already said made a frieze all around the church, it is obvious that the hammer beams had to have the same height in both parts of the building, interrupted only by corner posts. In the plan as projected the gable triangles also have frames, in this case formed by the horizontal gable beam and the sloping rafters. Also the gable walls are filled out with wide vertical planks.

The excavation at Hørning made it clear that the bottoms of the wall planks had stood in foot timbers. In the upper side of such timbers a groove would have been cut to hold the lower ends of the wall planks.

The outer face of the Hørning hammer beam was carved in strong relief, while its inner face was smooth (figs. 2 and 6). The shaping of the wall planks aimed at a similar contrast, i.e. a strong relief effect on the outside, which would be accentuated by shadows cast by the sun, and a smoother inner surface.

The 12 cm wide notch in the upper edge of the Hørning hammer beam is the only evidence we have of the roof construction. Probably truss construction was used, which has the good feature that the trusses only weigh on the walls vertically. In Garde church on Gotland the original Romanesque roof is preserved under the Gothic roof (Alsløv et al. 1978). The elegantly shaped Romanesque rafters in this church appear to be re-used timbers and may have come originally from an earlier stave church. In all events they have been C-14 dated to A.D. 940 ± 100 (Sveriges Kyrkor: Gotland, 288). Trusses of Romanesque type are the best suggestion for the reconstruction of the roof timbering at Hørning. A recess on the otherwise smooth inner side of the hammer beam suggests that a ceiling may originally have been nailed on the underside of the beams (fig. 6).

In Garde church part of the Romanesque roof covering also survives. It is made of very large pointed oak shingles, laid on boarding. The ridge, which is crowned by a torus with rope moulding, survives also, and in our projected plan the shingles, boarding, and roof ridge will be copied from the Gotland model.

The black background colour of the hammer beam is our reason for painting the church black with the framing emphasized by raised red edges on the posts similar to those along the lower edges of the hammer beams (fig. 7).

We know nothing of the internal arrangements of the Hørning stave church, and no decisions have yet been made how they will be reconstructed. This matter will be taken up when the church has been built.

Jens Jeppesen & Holger Schmidt

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Fra og med årgang 2022 er artikler udgivet i Kuml med en licens fra Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Alle tidligere årgange af tidsskriftet er ikke udgivet med en licens fra Creative Commons.