Fertility Sacrifices in the Early Iron Age of SW Funen. -Private or Collective?

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.7146/kuml.v39i39.111965Keywords:

Fertility sacrifice, early iron age, iron age, funenAbstract

Fertility Sacrifices in the Early Iron Age of SW Funen - Private or Collective?

Although fertility sacrifices are a widespread phenomenon both in time and space, they are a problem on which not a great deal of research has been done. One of the most important questions is the definition of a sacrificial deposit (Becker 1937; Stjernquist 1968). Religious actions and their place in society have become more relevant with the increasing interest being taken in prehistoric social structures. Collective rituals such as the war booty sacrifices have been considered as replacing smaller sacrifices made at the level of families (Geisslinger 1968) or individuals (Fabech 1991). Closer examination of the sacrificial deposits from Bukkerup Langemose (1) suggest that these should no longer be regarded as expression of individual actions. In the case of Bukkerup Langemose there seem to have been two sacrificial models between which one could choose. T1 consisted of the limb bones of a small cow, its tether in the form of a bast rope and wooden tethering peg, and a little drinking cup of clay. T2 was a halved large pot together with a piece of raw clay. These two are sometimes combined (T3, fig. 2). In some cases there have also been found human bones, among them those of a 30-45-year old man (3), that have been dated by C-14 to ca. 220 A.D. (4). The T1 and T2 models are shown by their pottery to date to between the end of the Pre-Roman Iron Age and the beginning of the Later Roman Iron Age (fig. 3). Throughout this nearly 400 year long period sacrifices were performed in exactly the same way, involving choosing a small cow, the method of dismemberment, and its deposition with tether and a specially chosen small drinking vessel (fig. 5). A mass spectrometrical analysis has shown that the vessels held a herbal drink including horsetail (Equisetum), a drink that was probably thought useful for fertility (Andersen 1995).

This contrasts with an example from Lundsgaard (Albrectsen 1946), where several instances of individual or family sacrifices occurred in houses. There were six houses and an equal number of animal sacrifices, indicating a less predetermined and more individual pattern. The natural conclusion is that there was a form of priest involved in the Bukkerup sacrifices, to ensure that the ritual rules were maintained and rites and ordinances kept alive for future generations.

When interpreting sacrificial deposits it is important to remember that they are symbols, and that only same of these symbols are preserved. There is little doubt that the Bukkerup type were agricultural sacrifices involving the more specific wish for fertility, as is emphasized by the fertility enhancing drink.

Further examples of sacrificial depositions of Bukkerup type have been found in the same geographical region. The most important were from Turup bog, where there were 7 sacrifices, each consisting of a small pottery vessel that had been placed on the bog surface together with the limb bones of a farm animal, which in five cases was a cow, in one a bull and in one a sheep. Also in a wetland area near Gummerup a pot together with the limbs of a young cow was found. The ritual pattern must have spread from Bukkerup to the surrounding villages through peaceful contacts. These fertility sacrifices ceased with the end of the Early Roman Iron Age, and at Kragehul, which is close to Bukkerup, we find the first large sacrifice of war booty. The centre of religious power had been moved a couple of kilometers to the south.

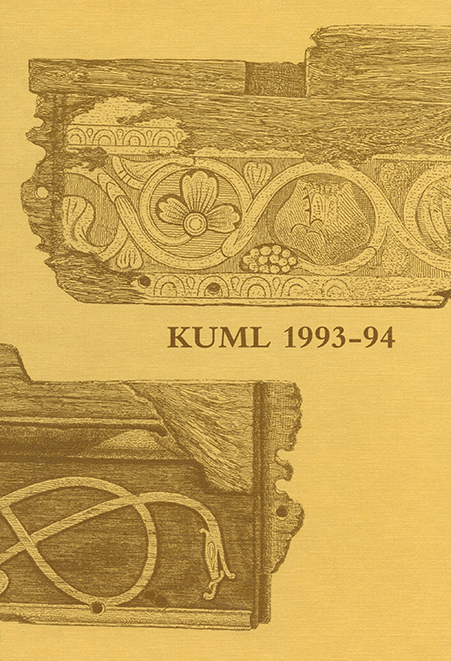

One of the pots from Bukkerup Langemose calls for particular attention (fig. 3). Its decoration had been applied with a comb or toothed implement and consists of a double interlace in five separate slings over the belly and lower part of the vessel. This may perhaps been seen as an early, and so far unique, example of interlace ornament on a Danish pot. The vessel can be dated to the transition between the Late Roman and the Early Germanic Iron Age (Jensen 1977; Petersen 1988).

Aase Gyldion Andersen

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Fra og med årgang 2022 er artikler udgivet i Kuml med en licens fra Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Alle tidligere årgange af tidsskriftet er ikke udgivet med en licens fra Creative Commons.