On the Aesthethics of Shame

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.7146/nja.v34i69.160694Keywords:

Feminist art, Affect theory, Performativity, Shame, Aesthetic CategoriesAbstract

Building upon theories of affect and emotion, this article focuses on how shame circulates through affective infrastructures and objects of emotion, engaging with the two distinctive arts practices of Maja Malou Lyse (DK, 1993) and Reba Maybury (UK, 1990). The article pursues the ways in which shame ties to aesthetics; how it is based in a feeling of exposure and rejection that may be negotiated through performative staging, but also how it links to aesthetic evaluation and the public sharing of what is preferably kept private.

References

1 Andrea Büttner, Shame (London: Koenig Books, 2020), 5.

2 “What remains for our pedagogy of unlearning is to build affective infrastructures that admit the work of desire as the work of an aspirational ambivalence. […] By definition, the common forms of life are always going through a phase, as infrastructures will.” Lauren Berlant, “The Commons: Infrastructures for Troubling Times,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 34, no. 3 (2016): 413.

3 Berlant, “The Commons,” 399, 414.

4 I borrow the term “infrastructural critique” from Marina Vishmidt, “Between Not Everything and Not Nothing: Cuts Toward Infrastructural Critique,” Former West: Art and the Contemporary after 1989, ed. Maria Hlavajova and Simon Sheikh (Utrecht: BAK / Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2017), 265–270.

5 Andrea Büttner, Shame, 10; Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004).

6 Similar to Raymond Williams’ definition of structures of feeling. Raymond Williams, “Structures of Feeling,” Marxism and Literature (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 128–135.

7 Vishmidt, “Between Not Everything and Not Nothing,” 266.

8 Martha C. Nussbaum, Hiding from Humanity. Disgust, Shame, and the Law (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2004), 173.

9 Büttner, Shame, 13; Eve K. Sedgwick, “Queer Performativity: Henry James’s The Art of the Novel,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 1 (1993): 4.

10 Tomkins is cited in, e.g., Sedgwick, “Queer Performativity: Henry James’s The Art of the Novel”: 6–7 and Lauren Berlant, “The Broken Circuit,” Cabinet Magazine 31, accessed April 19, 2024, https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/31/najafi_serlin_berlant.php.

11 The etymology of the word “shame” suggests that its original meaning was “cover.” “Outside Germanic no root of corresponding form and sense has been found, but many scholars assume a pre-Germanic *skem-, variant of *kem- to cover (Germanic *hem-: ham- as in hame n.1), ‘covering oneself’ being the natural expression of shame.” “Shame,” in Oxford English Dictionary, accessed September 9, 2025, https://www.oed.com/dictionary/shame_n?tab=etymology.

12 Carsten Stage, Skam, Tænkepause 68 (Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2019), 7.

13 Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 103.

14 “A relation of cruel optimism exists when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing. It might involve food, or a kind of love; it might be a fantasy of the good life, or a political project […] These kinds of optimistic relation are not inherently cruel. They become cruel only when the object that draws your attachment actively impedes the aim that brought you to it initially.” Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 1.

15 Sedgwick, “Queer Performativity,” 12 and 14.

16 Sedgwick, “Queer Performativity,” 5.

17 Sedgwick, “Queer Performativity,” 12.

18 Sedgwick, “Queer Performativity,” 14.

19 Sedgwick, “Queer Performativity,” 5 and 6.

20 Sedgwick, “Queer Performativity,” 4.

21 Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 103.

22 Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 106.

23 Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 11.

24 Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 10.

25 Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 10.

26 Ahmed here draws upon the etymology of “emotion” stemming from the latin “emovere” meaning to shake or stir.

27 See for instance: Maria Kjær Themsen, “Dansk samtidskunsts dulle realiserer en gammel feministisk våd drøm,” Information, August 23, 2019; Barbara Hilton, “Det mest radikale ville nok være at give min krop fri,” interview with Maja Malou Lyse, Eurowoman 292 (May 2022): 36–49; Christopher Mygind Juul, “Et opgør med pornotopien,” Costume (March–April 2021): 56.

28 Maja Malou Lyse in an interview with Freja Bech-Jessen, Costume (March–April 2021): 49. Translation by the author.

29 It is important to note here that it has not been possible to verify how many of the models in question spoke out in regard to this matter and therefore difficult to ascertain whether the images are depictions of “autonomous” female sexuality as the exhibition puts forth, even if it remains probable. A former Page 9 Girl, Pia Fris Laneth, who posed as a Page 9 Girl when 20 years old in 1975 and at 15 in the magazine, Ugens Rapport, has pronounced that she posed entirely voluntary and in an expression of sexual liberation. Pia Fris Laneth, interviewed by Louise Lindblad and Mette Byriel-Thygesen, in Sexhundredetallet (lit. “The Sexteenth Hundred”), a podcast produced by the National Museum of Denmark, season 2, episode 4. The case around the archive entailing images of minors is described in an article from Berlingske, “Side 9-arkiv med nøgenbilleder af mindreårige skal alligevel ikke destrueres,” Berlingske, June 20, 2023, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.berlingske.dk/kultur/side-9-arkiv-med-noegenbilleder-af-mindreaarigeskal-alligevel-ikke.

30 Signe Uldbjerg Mortensen, “Defying Shame,” MedieKultur 67 (2020): 110. The term “shame anxiety” is defined by Léon Wurmser, who differentiates between shame affect, shame anxiety, and shame as a reaction formation. Léon Wurmser, “Primary Shame, Mortal Wound and Tragic Circularity: Some New Reflections on Shame and Shame Conflicts,” The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 96, no. 6 (2015): 1615–1634.

31 Ibid., 115. Another discussion is also whether the type of social justice—judgments based on shame rather than guilt—is constructive or expedient. Clearly, there have been examples of shaming and public disgrace that did not follow customary legal principles. The discussion is linked to the distinction between shame and guilt— something that Martha Nussbaum has explored in depth, but which I will not go into further in this context.

32 Karl Marx in a letter to his friend Arnold Ruge in 1843 writes: “You look at me with a smile and ask: What is gained by that? No revolution is made out of shame. I reply: Shame is already a revolution of a kind… Shame is a kind of anger which is turned inward. And if a whole nation really experienced a sense of shame, it would be like a lion, crouching ready to spring.” Karl Marx, “Letters from the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher,” in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Collected Works, vol. 3 (New York: International Publishers, 1975), 133. As quoted in Büttner, Shame, 19.

33 See, for instance, Amia Srinivasan, The Right to Sex (London: Bloomsbury, 2022).

34 See, for instance, Tim Stüttgen, ed., Post/Porn/Politics (Berlin: b_books, 2009) and Martha Nussbaum, “Objectification,” Philosophy and Public Affairs 24, no. 4 (Fall 1995): 249–291.

35 Reba Maybury, Faster than an Erection, published on the occasion of the exhibition Faster than an Erection, June 2–September 12, 2021, at MACRO – Museum of Contemporary Art of Rome (Rome: MACRO, 2021), 10.

36 Maybury, Faster than an Erection, 33.

37 Maybury, Faster than an Erection, 24.

38 Nussbaum founds her analysis on the theories of Erving Goffman, Stigma – Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (New Yersey: Englewood Cliffs, 1963), and the developmental psychology and attachment theories of Donald Winnicott and John Bowlby.

39 Nussbaum, Hiding from Humanity, 233. This type of penalty refers to amends of humiliation or shaming in response to acts perceived as deviant/unacceptable behavior, but which does not necessarily endanger anyone, e.g. urinating in the street; drinking alcohol (driving with alcohol in the blood as an exception here); gambling etc.)—the main point being the public display and humiliation of the person being penalized. The distinction between guilt and shame lies at the core of Nussbaum’s analysis. From a legal perspective, Nussbaum discusses shame judgments and their negative effects and is interested in how it can be that certain individuals and groups lean towards shaming as punishment. She is very critical of judging based on shame, as it will stick to the individual and perhaps also to the individual’s entire family and circle of friends: In shaming and shame penalties you have not just done something wrong, you are wrong.

40 Maybury, Faster than an Erection, 10.

41 Jeppe Ugelvig, “Reba Maybury Deconstructs the Sexual-Economic Contract,” Frieze, 9 May 2024, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frieze.com/article/reba-maybury-happy-man-2024-review.

42 Ugelvig, “Reba Maybury Deconstructs the Sexual- Economic Contract.” Whereas Ugelvig writes “the John” in Faster than an Erection, this is consequently spelled “the john.”

43 Reba Maybury in conversation with Lucy McKenzie, “An Enlightenment to Entitlement,” in Mr V Neck and Mr Polo Shirt are Friends, Simiana, October 2024, accessed September 11, 2025, https://strapi.ssiimmiiaann.org/uploads/Reba_Maybury_646c4c7644.pdf.

44 Maybury in conversation with Lucy McKenzie, “An Enlightenment to Entitlement.”

45 Lauren Berlant, “The Broken Circuit,” Cabinet Magazine 31, accessed 19 April, 2024, https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/31/najafi_serlin_berlant.php.

46 Preciado analyses how erotic imagery is not included into the history and institutions of art, concerned with upholding the distinction between a critical subject and the “imbecile masturbator.” Preciado writes: “[A] new historiography of art is being built in which porn, prostitution and feminism aren’t part of the same story. Segregated into different rooms, contexts and concepts, good girls and good lookers aren’t allowed make history together.” Beatriz (Paul) Preciado, “Museum, Urban Detritus and Pornography,” Zehar 64 (2008): 32.

47 Freud argues that the creative writer through the aesthetic expression delivers his or her forbidden (i.e., shameful) fantasies in fictional form to a reader, which readers then gain pleasure from when reading. Sigmund Freud “Creative Writers and Day-Dreaming,” in On Freud’s Creative Writers and Day-dreaming, ed. Ethel Spector Person, Peter Fonagy, and Sérgio T. Figueira (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995 [(1908)]), 13.

48 Büttner, Shame, 10.

49 See, for instance, Berlant, “The Commons,” and Thierry de Duve, “This is Art: Anatomy of a Sentence,” Artforum, April 1, 2014, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.artforum.com/features/thierry-de-duve-on-aesthetic-judgment-219746/.

50 Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories. Zany, Cute, Interesting (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 2012), 13.

51 Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories, 2.

52 Ngai, Ugly Feelings, 2.

53 Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories, 41.

54 See, for instance, Taina Bucher, If… then: Algorithmic Power and Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018) and Justin Grandinetti and Jeffrey Bruinsma, “The Affective Algorithms of Conspiracy TikTok,” Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, no. 3., vol. 67 (2023): 274-293.

55 Sedgwick, “Queer Performativity,” 12.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

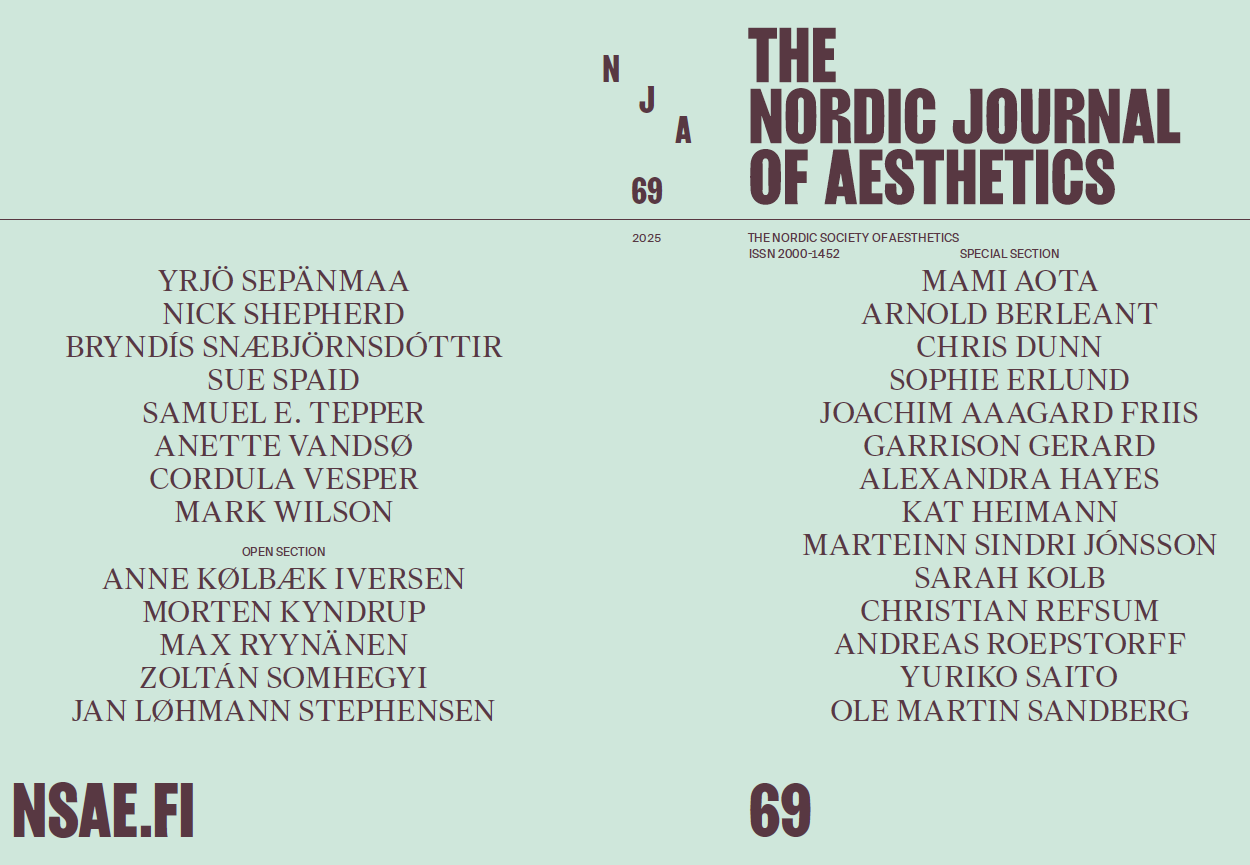

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Anne Kølbæk Iversen

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See The Effect of Open Access).