Towards an Aesthetics of Friendship

Ali Smith's Autumn

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.7146/nja.v34i69.160668Keywords:

Friendship, Love, Joint Attention, Collage, Everyday Aesthetics, Ali SmithAbstract

The first part of this article argues that aesthetic aspects play a crucial role in the formation and maintenance of friendships. While most philosophers of friendship emphasize ethical concerns, I draw inspiration from Alexander Nehamas’s predominantly aesthetic approach in On Friendship (2016). Nehamas claims that deep friendships depend on a strong fascination with the friend’s unique characteristics.

Although this may be true, I argue that friendship relies more fundamentally on the mutual appreciation of shared experiences, which includes a third entity: an object of interest, a situation, or the atmosphere created between those involved.

The second part of the article analyzes how Ali Smith portrays friendship as a process of sharing experiences in her novel Autumn (2016), with a focus on forms of attention, observations, and discourse. The reading also supports the hypothesis that the novel genre is a particularly rich source for exploring the significance of friendship.

References

1 “Aesthetics” is here used in a wide sense, as in Alexander Baumgarten’s original use of the term when he defined “aesthetics” as a general “science of perception that is acquired by means of the senses.” See Alexander Baumgarten, “Prolegomena to Aesthetica,” in Art in Theory: 1648-1815: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, ed. Charles Harrison, Paul Wood and Jason Gaiger, trans. Susan Halstead (Blackwell, 2000), 489. An aesthetics of friendship should then concern itself with how one perceives the world in the company of friends, or with people who might become friends.

2 Alexander Nehamas, On Friendship (Basic Books, 2016), Kindle Edition. See also Sheila Lintott, “Aesthetics and the Art of Friendship,” in Thinking about Friendship, ed. Damian Caluori (Palgrave Macmillan), 240, who “is pursuing an analogy between art and friendship […].”

3 Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, trans. H. Rackham (Harvard University Press, 1926), Loeb Classical Library.

4 Aristotle, Eudemian Ethics, trans. C.D.C. Reeve (Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2021).

5 See Herbert James Paton, “Kant on Friendship,” in Friendship: A Philosophical Reader ed. Neera Kapur Badhwar (Cornell University Press), 142. In “Lecture on Friendship” Kant operates with a three-part distinction similar to Aristotle between friendships of “need,” of “taste” (aesthetical friendships) and friendships of moral attitude. See Other Selves: Philosophers on Friendship, ed. Michael Pakaluk (Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1991), 214. Kant also discusses friendship in § 46–48 in his late work from 1797 The Metaphysics of Morals (Die Metaphysik der Sitten).

6 See Aristotle, Eudemian Ethics, [EE1236a15-1238b14] 114–120.

7 In the Nicomachean Ethics, 139, 1156b) Aristotle writes that, “[…] those who wish good things to their friends for the friend’s own sake are friends most of all […].” He nuances this argument in several places. It is necessary for him that there is some kind of balance in the friendship. If one gives more than the other, the friendship will eventually dissolve. Only when the friends are virtuous, this problem can be avoided.

8 Aristotle, Eudemian Ethics, 115.

9 Nehamas, On Friendship, 197.

10 Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics [NE1170 b10], 563–565.

11 Cited from Nehamas, On Friendship, 119.

12 See chapter 3, “A Structure of the Soul: Friendship and the Arts” in Nehamas, On Friendship, 64–83.

13 Claus Emmeche, “Dialogic Knowledge in Friendship as Represented by Literature and Research,” in Tempo da Colheita: Homenagem à Lucia Santaella /Harvest Time: Festschrift for Lucia Santaella, ed. Priscila Monteiro Borges and Juliana Rocha Franco (Editora FiloCzar, 2023), chapter 21, 327–348.

14 In “Friendship in a Time of Neoliberalism,” in Love Etc.: Essays on Contemporary Literature and Culture, ed. Rita Felski and Camilla Schwartz (University of Virginia Press, 2024). Camilla Schwartz presents a long list of contemporary female novelists focusing on friendship.

15 See e.g. Gregory Jusdanis’ A Tremendous Thing: Friendship from the Iliad to the Internet (Cornell University Press, 2014). On female friendship in literature, see e.g. Janet Todd: Women’s Friendship in Literature (Colombia University Press, 1980) and Sharon Marcus: Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England (Princeton University Press, 2007).

16 Alain Badiou and Nicolas Truong, In Praise of Love, trans. Peter Bush (Serpent’s tail, 2012), 29 ff.

17 Claus Emmeche explains “blood brotherhood” as “A form of ‘ritual friendship’ (q.v.) that refers to the ritual commingling or drinking of the blood of the participants, thus creating an alliance of trust between those involved, implying mutual support, loyalty, or affection.” See Emmeche, “Dialogic Knowledge in Friendship,” 56. This practice has been mentioned by many classical writers, beginning with Herodotus (5th c. BCE). It is also described in sagas from central Europe, Scandinavia, and Asia. The custom has also been documented in Africa.

18 See the chapter “Theory of the Quasi-Object,” in Michel Serres’s The Parasite (The John Hopkins University Press, 1982), 224–234. Here, Serres develops a social theory of interaction where an object facilitates social behavior. The quasi-object (Serres uses the example of a rugby ball) is neither quite natural, nor quite social. “This quasi-object is not an object, but it is one nevertheless, since it is not a subject, since it is in the world; it is also a quasi-subject, since it marks or designates a subject who, without it, would not be a subject. […] This quasi-object, when being passed, makes the collective, if it stops, it makes the individual.” (p. 225)

19 Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, trans. H. Rackham (Harvard Loeb Classical Library, 1926), DOI: 10.4159/DLCL.aristotle-nicomachean_ethics.1926, [NE 1170b11], 565.

20 April Flakne explains that “nous” is “[…] the agent intellect responsible for “concept-getting,” and hence rationality.” See April Flakne, “Embodied and Embedded: Friendship and the Sunaisthetic Self,” Époché: A Journal for the History of Philosophy 10, no. 1 (Fall 2005): 41.

21 Flakne, “Embodied and Embedded: Friendship and the Sunaisthetic Self,” 39.

22 Giorgio Agamben, “The Friend,” in What is an Apparatus?, trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Stanford University Press, 2009), 31–35. (Italian original, “L’amico,” 2007.)

23 In the introductory “Translator’s Note,” Agamben’s translators, David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella, express their gratitude to the author for his assistance. They specify that “English translations of secondary sources have been amended in order to take into account the author’s sometimes distinctive Italian translations. (Agamben, What is an Apparatus?, 2009.)

24 Agamben, “The Friend,” 31.

25 Agamben, “The Friend,” 36.

26 Flakne, “Embodied and Embedded: Friendship and the Sunaisthetic Self,” 49.

27 Flakne, “Embodied and Embedded,” 48.

28 Sara Brill, Aristotle on the Concept of Shared Life (Oxford University Press, 2020), 39–85.

29 Ali Smith, Autumn (Hamish Hamilton 2017), 3. Charles Dickens’ opening of A Tale of Two Cities (Wordsworth Editions Limited, 1993), 3: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times […].”

30 Smith, Autumn, 117.

31 Smith, Autumn, 117.

32 Smith, Autumn, 119–120.

33 Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde (University of Minnesota Press, 1984), 78.

34 Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, 79.

35 Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, 80.

36 E.g. Smith, Autumn, 59–61.

37 Smith, Autumn, 157, 258.

38 Emily Hyde writes in “That was now,” in Public Books: A Magazine of Ideas, Arts and Scholarship, August 3, 2017, that “In the early 1990s, just when Daniel and Elisabeth embark on their friendship, scholars in fact discovered Boty’s paintings stored in an outhouse on her brother’s farm. It makes sense, then, that in 2003, when Elisabeth is 18, she finds an art catalogue in the bargain section of a London bookstore and opens to Untitled (Sunflower Woman), c. 1963, by Pauline Boty, the very painting Daniel had described to her years before.”

39 Smith, Autumn, 160.

40 Smith, Autumn, 160.

41 Smith, Autumn, 160.

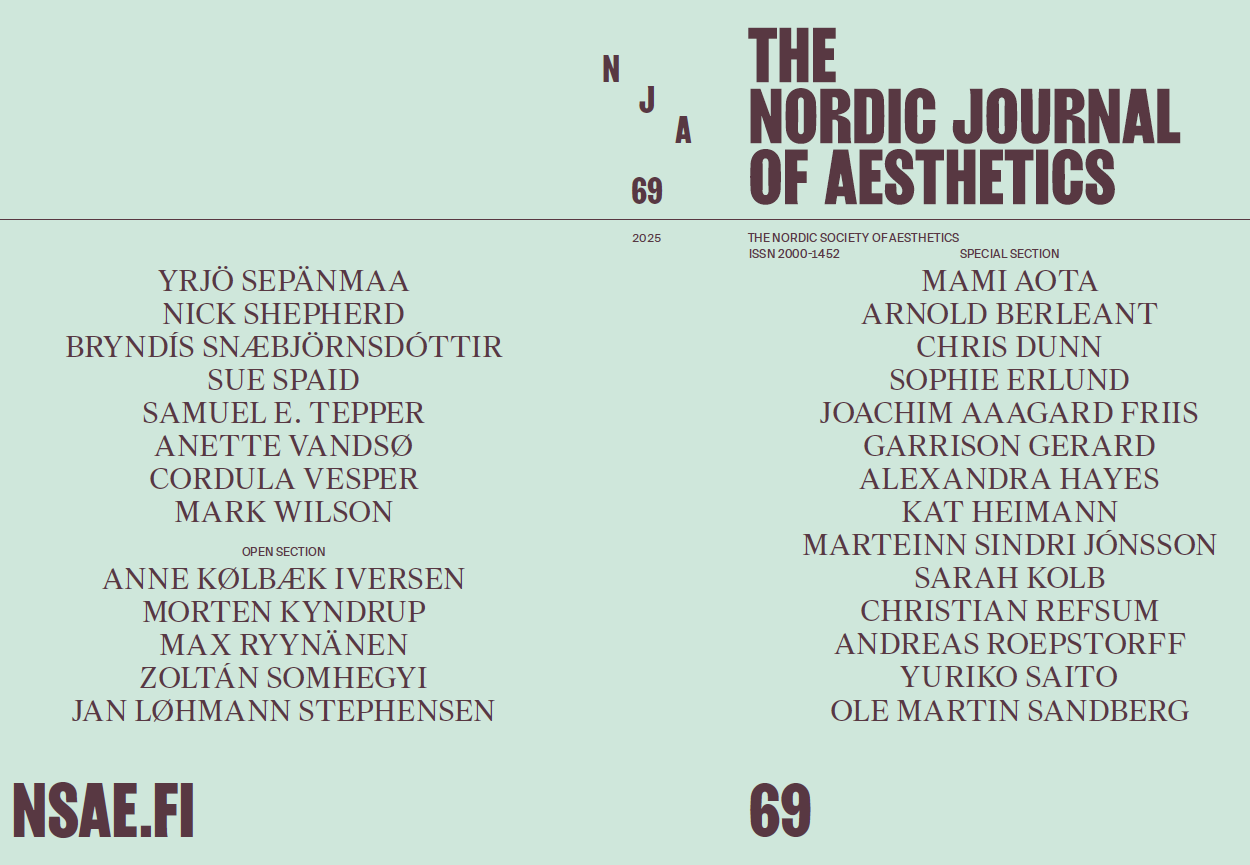

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Christian Refsum

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See The Effect of Open Access).