Do Clouds have Politics?

Reflections on Aesthetic Encounter, Nature, and Power

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.7146/nja.v34i69.160667Keywords:

Philosophy of Technology, Environmental Philosophy, Political Ecology, Political Philosophy, Nature, Politics, Transcendence, AestheticsAbstract

This paper considers contemporary academic discourse concerning the relationship between nature and the political. The main question it addresses is the significance of aesthetic encounter with nature, specifically if and to what extent nature’s display can be understood as providing a vantage or connection to something beyond human power relations. It does so by drawing from some reflections in the philosophy of technology and environmental philosophy concerning the nature of the artifactual and the artifactuality of nature. The title itself is derived from Langdon Winner’s essay Do Artifacts Have Politics? In considering this question, Winner undertakes an analysis of New York City underpasses and can be seen as a precursor to political ecology. This paper will thus consider the limits of a shared understanding within political ecology of nature as inherently and inseparably political. It distinguishes between socially totalizing and socially transcendent views. It incorporates phenomenological reflections and responds to certain key philosophical texts such as Bill McKibben’s The End of Nature, Eric Katz’s criticisms of ecological restoration, Stephen Vogel’s Thinking Like a Mall and long-standing relevant contemplations ranging from Thoreau to the Tao Te Ching. This topic is increasingly pertinent in an era of climate change and other global environmental crises.

References

1 Davis Guggenheim, (director), An Inconvenient Truth: A Global Warning. Paramount, 2006.

2 Rebecca Sohn, “What Are Nacreous Clouds?” Space.com. Published March 2, 2024. https://www.space.com/what-are-nacreous-clouds-how-do-they-form.

3 You can see the mentioned photos here: https://www.

flickr.com/photos/199188099@N05/53433704828/; https://www.flickr.com/photos/199188099@ N05/53433986385/; https://www.flickr.com/ photos/199188099@N05/53433565391/; https:// www.flickr.com/photos/199188099@N05/53433996760/.

4 Tori Otten, “Donald Trump to Voters: Look at This Disturbing Word Cloud.” The New Republic. Published December 27, 2023. https://newrepublic.com/post/177738/trump-2024-word-cloud-dictatorship.

5 Another example was a violent hailstorm I was caught in in Boulder, Colorado on summer day. I took cover under an elevated footbridge with a few others. Two of us exchanged ponderings about climate change. The storm itself was worrying yet elating, yet this elation ended in further elevated worry rather than elevation.

6 Langdon Winner, “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” In Computer Ethics, 177–92. New York: Routledge, 2017.

7 Alan Watts, Tao of Philosophy. Tuttle Publishing, 1999.

8 Winner, “Do Artifacts Have Politics?”

9 Eric Katz, “The Big Lie: Human Restoration of Nature.” Readings in the Philosophy of Technology 12, no. 1 (1992): 231–41.

10 Nicholas Lemann, “Why Hurricane Katrina Was Not a Natural Disaster.” The New Yorker. Published August 26, 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/books/under-review/why-hurricane-katrina-was-not-a-natural-disaster. See also: Chester W. Hartman and Gregory D. Squires, eds. There Is No Such Thing as a Natural Disaster: Race, Class, and Hurricane Katrina. London: Taylor & Francis, 2006. Neil Smith, “There’s No Such Thing as a Natural Disaster.” In Understanding Katrina: Perspectives from the Social Sciences, June 11, 2006.

11 And perhaps the ultimate exemplar of the sublime?

12 Peter D. Dwyer, “The Invention of Nature.” In Redefining Nature: Ecology, Culture and Domestication, edited by R. Ellen and K. Fukui. Oxford: Berg, 1996.

13 William Chaloupka and Cawley R. McGreggor, “The Great Wild Hope: Nature, Environmentalism, and the Open Secret.” In The Nature of Things: Language, Politics, and the Environment, 3–23. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

14 Doreen Massey, Space, Place and Gender. John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

15 Mark Woods, Rethinking Wilderness. Broadview Press, 2017.

16 Steven Vogel, Thinking Like a Mall: Environmental Philosophy After the End of Nature. MIT Press, 2015.

17 Vogel, Thinking Like a Mall, 196–97.

18 Johanna Oksala, “Foucault’s Politicization of Ontology.” Continental Philosophy Review 43, no. 4 (2010): 445–66.

19 Timothy Morton, “The Ontological Is Political.” YouTube. Published September 27, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QKrRNK6b4sg.

20 Though I am not the first: “Han’s critical claim is that a transcendental reading of the power-knowledge nexus means that, far from being a contingent and historically given configuration, it turns into an independent quasi-metaphysical entity capable of determining the possible forms and domains of knowledge and transforming itself in history. She claims that despite Foucault’s explicit denials, secretly there is a metaphysics of power at work in his thought. Powerknowledge becomes an essence definable in itself, returning Foucault to the sort of metaphysics that genealogy sought to combat by giving primacy to perspective and interpretation against any essentialist ontology. While Han acknowledges that the other possibility would be to accept Foucault’s explicit description of power-knowledge as an analytic grid, a mere theoretical tool designed to clarify the conditions of acceptability of a system, such acceptance would only land him in even more serious trouble. He would avoid the metaphysics of power, but the problem with a mere analytic grid is that it is deprived of any foundation.” See Oksala, “Foucault’s Politicization of Ontology,” 456–57.

21 Power-mena (after phenomena).

22 Critical minded power reductionists might “link the sublime to mesmerizing and subduing political devices”; “In more recent decades... [B]eauty has become suspect... Beauty has in some quarters become bound up in ideology... [T]here is no denying that the veneration of the beauty of nature, which Wordsworth made the fount of his philosophy, has largely ceased to figure in high culture since modernism contemptuously swept it aside...” Michael McCarthy, The Moth Snowstorm: Nature and Joy. New York: New York Review of Books, 2016. Also, for instance, “In a bus chartered by the organizers of an Association for the Study of Literature and Environment (ASLE) conference, the person beside me prepared me for the Grand Canyon as only an academic can. It was a ninety-minute ride from Flagstaff to the South Rim, but it felt much longer. The professor on my right made sure I understood the relation between tourism, post-industrialism, and the commodification of landscapes. It turns out that the Romantics, feeling acute competition with the agents of the Industrial Age, attempted to accrue social capital by becoming experts in their own distinctive enterprise—the manufacturing of beauty and the sublime. The Romantics, I was told, sold the sublime in works of art to an uncouth middle class hungry for the status that accompanies culture and education. I was assured that the only way to escape the spell of the wild and the sublime was to interrogate its bourgeois history. I could hardly wait. And then, in the middle of this private lecture, the brilliant and ineffable Grand Canyon suddenly loomed out the bus window: a staggering wilderness of rock and light rising from the land in one organic surge. A deep silence filled the bus. After that, I didn’t hear another word from the professor on my right about producers and consumers of wild beauty.” Mark Cladis, “Radical Romanticism and Its Alternative Account of the Wild and Wilderness.” ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 25, no. 4 (2018): 835–57.

23 Henry David Thoreau, “Walking.” In The Essays of Henry D. Thoreau: Selected and Edited by Lewis Hyde. Macmillan, 2002.

24 Henry David Thoreau, “Slavery in Massachusetts.” In Collected Essays and Poems. Library of America, 2001.

25 E.g., “Let us settle ourselves, and work and wedge our feet downward through the mud and slush of opinion, and prejudice, and tradition, and delusion and appearance, that alluvion which covers the globe, through Paris and London, New York and Boston and Concord, through church and state, through poetry and philosophy, till we come to a hard bottom and rocks in place, which we can call reality, and say, This is, and not mistake...” Henry David Thoreau, Walden: A Fully Annotated Edition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

26 Ted Geier, “Review of Aesth/Ethics in Environmental Change: Hiking through the Arts, Ecology, Religion and Ethics of the Environment, edited by Sigurd Bergmann, Irmgard Blindow, and Konrad Ott. Environmental Philosophy 11, no. 1 (2014): 131–35.

27 Vogel, Thinking Like a Mall, 236.

28 Vogel, Thinking Like a Mall, 238.

29 Vogel, Thinking Like a Mall, 12.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

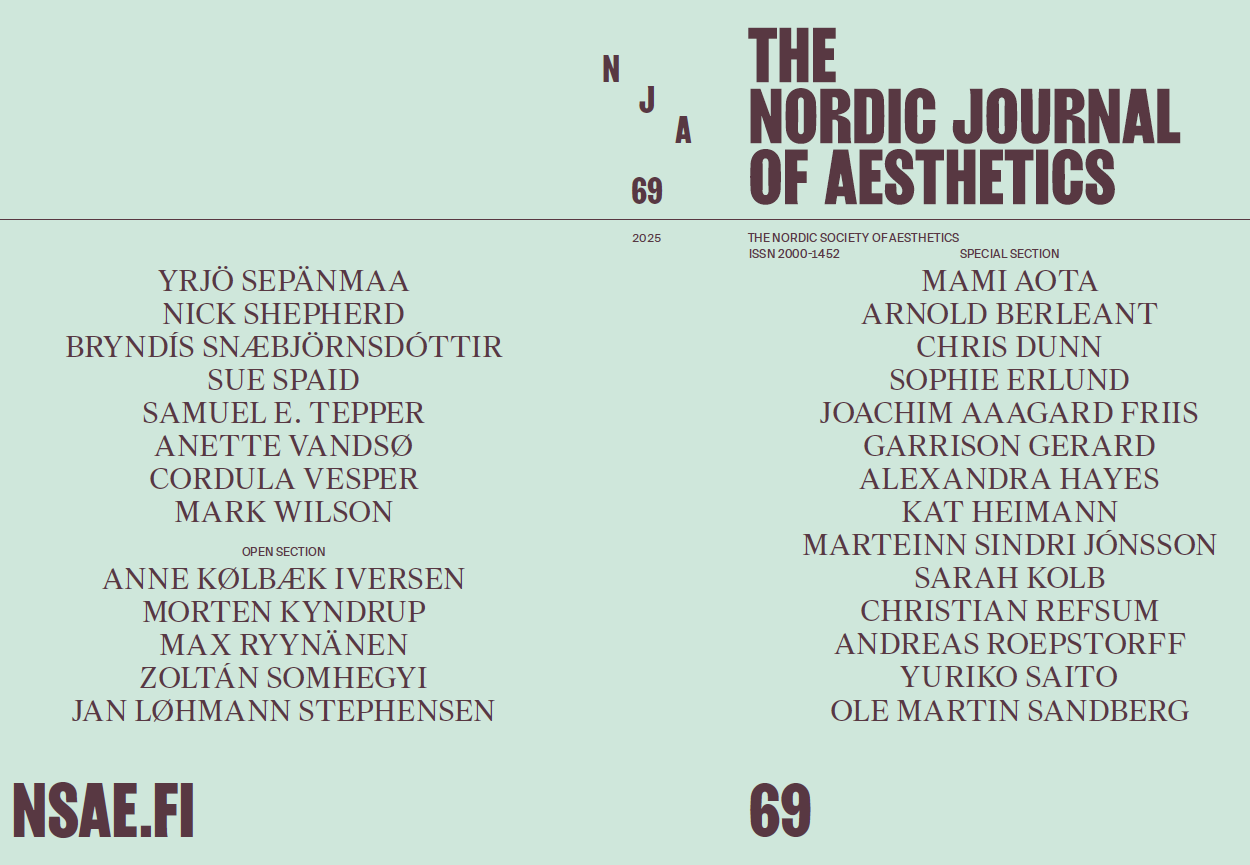

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Chris Dunn

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See The Effect of Open Access).