Aesthetics and Crisis in the new “New Iceland”

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.7146/nja.v34i69.160666Keywords:

New , The Populist Challenge and the Nativist Front, New Frontiers in the Dualistic Colonial Experience, Commoning of Cultural ExpressionAbstract

This contribution asks how Angela Dimitrakaki’s 2017 analysis of the New “New Europe” may be adapted to characterise socio-political developments in Iceland since 2008. Guided by a range of aesthetic practices that respond, enact or engage in some way with the realities of what may succinctly be termed the New “New Iceland,” the article identifies three initial socio-political parameters to qualify this condition, The Populist Challenge and the Nativist Front, New Frontiers in the Dualistic Colonial Experience and The Commoning of Cultural Expression. With reference to recent scholarship in art and cultural theory, political science, decolonial anthropology and feminist literary theory, it combines qualitative, theoretical and historical perspectives to produce a comprehensive discussion with an interdisciplinary relevance for future research on the paradigm of the New “New Europe.”

References

1 Angela Dimitrakaki, “Art, Instituting, Feminism and the Common/s: Thoughts on Interventions in the New ‘New Europe,’” draft chapter in Inside Out: Critical Artistic Discourses Concerning Institutions, ed. Suzana Milevska and Alenka Gregoric (Ljubljana City Art Gallery, 2017). I am grateful to students and colleagues at the Iceland University of the Arts and the University of Bifröst, Jón Karl Helgason, the editors, especially Jóhannes Dagsson and Sólrún Una Þorláksdóttir, and an anonymous reviewer for making generous suggestions for my work.

2 Dimitrakaki, “Art, Instituting, Feminism and the Common/s,” 2.

3 My dissertation, written at the Chair of Art Theory and Curating at Zeppelin University and titled Infrastructures

of the Public Sphere: Socially Engaged Art and Curatorial Practice in the New “New Germany” is the outcome of a three-year long research project, FEINART, funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement. The project was devoted to the future of European independent art spaces and socially and politically engaged art practices. For further information about the research project see FEINART, “About,” accessed August 29, 2025, https://feinart.org/about/

4 My use of the term parameter is intentional and refers to how the aesthetic qualities of electronic instruments are shaped. Sound is synthesised by qualifying electronic oscillators with multiple parameters, leading to the emergence of complex structures that continuously feedback and affect each individual parameter. Thus, no parameter is an isolated topography, but rather a dynamic and integrated structure within a broader soniclandscape.

5 Statistics Iceland. “At-Risk-of-Poverty Rate 9.0% in 2023.” January 8, 2025. https://statice.is/publications/news-archive/quality-of-life/at-risk-of-povertyrate-2023/. However, according to an equally recent report by UNICEF, child poverty has increased by eleven percent in Iceland between the years 2012–14 and 2019–21. The only European country to surpass this rate of development was the UK, where poverty increased by twenty percent in the same period. See United Nations Regional Information Centre (UNRIC). “Mikil fjölgun barna sem lifa við fátækt á Íslandi.” Accessed August 29, 2025. https://unric.org/is/mikil-fjolgun-barna-sem-lifavid-fataekt-a-islandi/#. Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind that poverty is a relative term, and in virtue of Iceland’s high living standards poverty may include factors such as insufficient heating or nutrition but also the availability of new clothing, technological amenities such as phones, or resources to celebrate birthdays or participate in leisure activities. For the full report, cf. UNICEF. “More Than 1 in 5 Children Live in Poverty in 40 of the World’s Richest Countries.” December 5, 2023. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/more-1-5-children-live-poverty-40-worlds-richestcountries.

6 Ágústa Eva Erlendsdóttir and Þorvaldur Bjarni Þorvaldsson. “Congratulations.” Song, 3:00. Sena, 2006.

7 See also two BA theses written at the Iceland University of the Arts on the matter, Anna María Tómasdóttir, “Hei, þú ógisslega töff — ég er að tala við þig!” (Bachelor thesis, Iceland University of the Arts, 2011); and Bjartur Örn Bachmann, “Til hamingju Ísland: Sylvía nótt og íslenska þjóðin í samhengi” (Bachelor thesis, Iceland University of the Arts, 2022).

8 It is important to note that Sylvía Nótt’s 2006 parody predates the actual financial crash. Jón Karl Helgason and Ásgeir Brynjar Torfason have discussed how aesthetic commentary on the cultural landscape in Iceland before the crash may be traced at least back to the literary works of Þráinn Bertelsson and Sigfús Bjartmars in 2004. See Jón Karl Helgason and Ásgeir Brynjar Torfason, “Hinn (al)þjóðlegi peningaleikur: Einkavæðing ríkisbanka í ljósi glæpasagna Þráins Bertelssonar,” Skírnir 195 (Autumn 2022): 319–54. The article was in turn prompted by an extensive review of Icelandic literature in relation to the financial crisis: Alaric Hall, Útrásarvíkingar: The Literature of the Icelandic Financial Crisis (2008–2014) (punctum books, 2020).

9 For a comprehensive study of these events, see for instance Paul E. Durrenberger and Gísli Pálsson, eds., Gambling Debt: Iceland’s Rise and Fall in the Global Economy (University Press of Colorado, 2015). See also Oxfam, “The True Cost of Austerity and Inequality: Icelandic Case Study,” Oxfam Case Study (September 2013), https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/301384/cs-true-costausterity-inequality-iceland-120913-en.pdf?sequence=69

10 See for instance the work of Kristín Loftsdóttir: “Vikings Invade Present-Day Iceland,” in Gambling Debt: Iceland’s Rise and Fall in the Global Economy, eds. Paul E. Durrenberger and Gísli Pálsson, 3–14 (University Press of Colorado, 2015); and Kristín Loftsdóttir, Crisis and Coloniality at Europe’s Margin: Creating Exotic Iceland (London: Routledge, 2019).

11 See especially Ingi F. Vilhjálmsson, Hamskiptin: Þegar allt varð falt á Íslandi (Reykjavík: Veröld, 2014); and Jóhann Hauksson, Þræðir valdsins: Kunningjaveldi, aðstöðubrask og hrun Íslands (Reykjavík: Veröld, 2011). For a comprehensive list of books that treat the crash historically and ethically, see the excellent conference archive Hrunið, þið munið, https://hrunid.hi.is/hrunbaekur/saga-sidferdi/

12 Historian and journalist Guðmundur Magnússon wrote the book Nýja Ísland: Listin að týna sjálfum sér (Reykjavík: JPV, 2008); but in his work the term “New Iceland” refers to the 40–50 years preceding the financial crash, rather than the aspirations for what would replace that older “New Iceland.”

13 In other words, as the journalist adds, “New Iceland is in fact Old Iceland.” Jón G. Hauksson, “Nýja Ísland,” Frjáls verslun 11 (2009): 42–43.

14 Cf. Oxfam, “The True Cost of Austerity and Inequality.”

15 Cf. Luis A. Gil-Alana and Edward H. Huijbens, “Tourism in Iceland: Persistence and Seasonality,” Annals of Tourism Research 68 (January 2018): 20–29.

16 Viðskiptablaðið, “Þúsund milljarða innviðaskuld.” August 10, 2024, https://vb.is/frettir/ thusund-milljardainnvidaskuld/.

17 Cristopher Crocker, “‘The First White Mother in America:’ Guðríðr Þorbjarnardóttir, Popular History, Firsting and White Feminism,” Scandinavian-Canadian Studies / Études scandinaves au Canada 30 (2023): 4. See also Inga Björk Margrétar Bjarnadóttir and Jovana Pavlović, “Fyrsta hvíta móðirin í geimnum: Kynþáttafordómar, hvítleikinn og mörk listarinnar,” Tímarit Máls og menningar 83, no. 3 (2022): 5–18; and Bryndís Björnsdóttir, “Endurhvítun: Nýja íhaldið og andspyrna í íslenskum myndlistarheimi,” Tímarit Máls og menningar 86, no. 2 (2025). Crocker relies on the pioneering work of Tinna Grétarsdóttir, “Unveiling the Work of the Gift: Neoliberalism and the Flexible Margins of the Nation- State,” in Flexible Capitalism: Exchange and Ambiguity at Work, ed. Jens Kjaerulff, 67–92 (New York: Berghahn, 2015). Already in 2010 Grétarsdóttir published a comprehensive treatise in Icelandic on Sveinsson’s work: Tinna Grétarsdóttir, “Á milli safna: Útrás í (lista) verki,” Ritið 1 (2010): 83–104.

18 Her story is recounted in two different sagas, Grænlendinga saga and Eiríks saga rauða, but the birthplace is accounted for in the latter. See Eiríks saga rauða, made available in the public domain by Snerpa, https://www.snerpa.is/net/isl/eirik.htm.

19 Crocker, “‘The First White Mother in America,’” 20–21.

20 Crocker, “‘The First White Mother in America,’” 21.

21 Iceland is traditionally conceived of as a homogenous nation state, and historically national identity has been effectively constructed in ethnic terms. The Icelandic sagas, that in many ways constitute Icelandic historical identity, romanticise the legacy of white Norsemen settling in the 9th and 10th century. While there were no indigenous populations in Iceland at the time, this Nordic expansion may still be understood in settlercolonial terms given the extensive marauding and slavery in the British Isles, Eastern Europe and beyond, that predicated economic progress and ensured social reproduction in the Nordic region. Moreover, Nordic cultural heritage may be seen to be constitutive of certain aspects of settler-colonial identity in the US and the symbols, and semantics of Nordic mythology and cultural identity have long inspired white supremacists in different national contexts. This was nowhere as pronounced as on January 6, as rioters stormed the US Capitol Building in Washington, led by a person wearing skin fur and a spiked horn helmet. See for instance Sólveig Ásta Sigurðardóttir, “Hidden in Plain Sight: Nordic Colonialism in American Literature from Reconstruction to the Immigration Act of 1924” (PhD diss., Rice University, 2022), https://repository.rice.edu/items/37d32149-6812-41ad-9a38-03378308adf3.

22 Eiríkur Bergmann, “Nordic Populism: Conjoining Ethno-Nationalism and Welfare Chauvinism,” in Democracy Fatigue: An East European Epidemy, ed. Carlos García-Rivero, 240–61 (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2023), 254. See also a broader contextualisation in Eiríkur Bergmann, Neo-Nationalism: The Rise of Nativist Populism (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

23 Oxfam, “The True Cost of Austerity and Inequality,” 3.

24 Oxfam, “The True Cost of Austerity and Inequality,” 3.

25 Clara E. Mattei, The Capital Order: How Economists Invented Austerity and Paved the Way to Fascism (Chicago University Press, 2022).

26 Dimitrakaki, “Art, Instituting, Feminism and the Common/s,” 2, 5.

27 As a matter of fact, The Centre Party has, since its establishment by former prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, invoked much of US and Europe’s far-right socio-political discourse. Its establishment followed the publication of Gunnlaugsson’s name in the so-called Panama Papers, that led to his expulsion as prime minister and leader of the Progressive Party. Early in their first parliamentary term, MPs of Miðflokkurinn were overheard expressing misogynistic and derogative views of disabled people in a public bar, which led to a major scandal. Despite these faults, the party has enjoyed increasing support through the COVID-19 pandemic and deepening frustrations with a broad coalition government in power between 2017 and 2024. For a more recent assessment, see Eiríkur Bergmann, “Iceland’s Deep-Rooted Nationalism and Recent Quasi-Populism,” in Aufstand der Außenseiter: Die Herausforderung der europäischen Politik durch den neuen Populismus, eds. Frank Decker et al., 299–312 (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2022).

28 Bergmann, “Nordic Populism,” 254.

29 This necessarily brief analysis is further reinforced by the findings of a recently published Master’s Thesis at the University of Iceland by Nazima Kristín Tamimi and supervised by Baldur Þórhallsson in the field of International Relations. See Nazima Kristín Tamimi, “Right-Wing Extremism in Iceland: Analyzing the Influence of UK and US Rhetoric on Icelandic Discourse” (Master’s thesis, Department of Political Science, University of Iceland, 2024).

30 Cf. Claudia Ashanie Wilson in conversation with Ragnhildur Helgadóttir, “Segir nýju útlendingalögin notuð í ‘skipulagða herferð,’” Heimildin, November 4, 2024, https://heimildin.is/grein/23126/segir-nyju-utlendingalogin-notud-i-skipulagda-herferd/

31 Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, “On the Turn Towards Liberal State Racism in Denmark,” e-flux Journal (January 2011), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/22/67762/ on-the-turn-towards-liberal-state-racism-in denmark.

32 Vassiliki Koutsogeorgopoulou, “Immigration in Iceland: Addressing Challenges and Unleashing the Benefits,” OECD Economics Department Working Papers, no. 1772 (Paris: OECD, 2023), https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-economic-surveys-iceland-2023_b3880f1a-en.html, 61.

33 See for instance Adrián Groglopo and Julia Suárez- Krabbe, Coloniality and Decolonisation in the Nordic Region (London: Routledge, 2023).

34 A case in point would be the limited access youth with non-Icelandic cultural background have had to higher education. Cf. Biljana Boloban, “Staða nemenda af erlendum uppruna í framhaldsskólum á Íslandi” (Bachelor’s thesis, University of Iceland, 2017).

35 Philipp Oltermann and Rachel Savage, “UK Court Sides with Icelandic Firm Over Artist’s Spoof Corruption Apology,” The Guardian, November 14, 2024, https:// www.theguardian.com/law/2024/nov/14/.icelandic-firm-samherji-artist-odee-fishrot-spoof-court

36 In the wake of these reports, Namibia’s justice minister and fisheries minister resigned and were at the time, together with eight others, awaiting trial in Namibia over allegations of fraud, corruption and racketeering. In Iceland, a criminal investigation is still ongoing, but no one has yet faced charges. In 2021, Samherji apologised for “mistakes” in a statement but denied any criminal offences apart from those admitted by whistleblower Jóhannes Stefánsson, the company’s director of operations in Namibia at the time of the alleged corruption. Oltermann and Savage, “UK Court Sides with Icelandic Firm Over Artist’s Spoof Corruption Apology.”

37 Oltermann and Savage, “UK Court Sides with Icelandic Firm Over Artist’s Spoof Corruption Apology”; Frederico Links and Ester Mbathera, “‘Right Now, I Cannot Survive:’ The Legacy Effects of the Fishrot Corruption Scandal on Fisheries Worker’s Lives,” Institute for Public Policy Research (November 2024), https://ippr.org.na/.wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Fishrot-HRIA-2-web.pdf

38 Gísli Pálsson and Agnar Helgason, “Figuring Fish and Measuring Men: The Individual Transferable Quota System in the Icelandic Cod Fishery,” Ocean and Coastal Management 28, no. 1–3 (1995): 117–46.

39 See especially the work of Unnur Dís Skaptadóttir, but her PhD focused on women’s labour on the Icelandic seaboard: Fishermen’s Wives and Fish Processors: Continuity and Change in Women’s Position in Icelandic Fishing Villages, 1870–1990 (PhD diss., University of Victoria, 1995), file:///Users/au340897/Downloads/_ Skaptadottir_Unnur+Dis_Anthro_38.2_1996.pdf.

40 Oxfam, “The True Cost of Austerity and Inequality.”

41 Oltermann and Savage, “UK Court Sides with Icelandic Firm Over Artist’s Spoof Corruption Apology.”

42 Oltermann and Savage, “UK Court Sides with Icelandic Firm Over Artist’s Spoof Corruption Apology.”

43 Kristín Loftsdóttir, “‘I’ve Come to Buy Tivoli:’ Colonial Desires and Anxieties in Iceland in a New Millennium,” Nordics.info, February 24, 2021, https://nordics.info/show/artikel/ive-come-to-buy-tivoli-colonial-desiresand-anxieties-in-iceland-in-a-new-millennium. In her text, Loftsdóttir refers to Aníbal Quijano, “Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality,” in “Globalization and the De-Colonial Option,” ed. Walter D. Mignolo, special issue, Cultural Studies 21, no. 2–3 (2007): 168–78; and her own earlier work, Kristín Loftsdóttir, “Being ‘The Damned Foreigner:’ Affective National Sentiments and Racialization of Lithuanians in Iceland,” Nordic Journal of Migration Research 7, no. 2 (2017): 70–78.

44 See for instance NGO Shipbreaking Platform, “Press Release: Prosecutor Launches Investigation after Icelandic Journalists Shed Light on Illegal Export of Toxic Ships to India,” 25 September 2020, https://shipbreakingplatform.org/breach-eu-wsr-godafosslaxfoss/ and Recycling International, “Icelandic Operator Acknowledges Fault Over Illegal Shipbreaking,” 2 October 2020, https://recyclinginternational.com/business/icelandic-operator-acknowledges-fault-overillegal-ship-breaking/31617/. I am aware that similar instances may precede the period that I have in mind, such as the controversial sourcing of bauxite by multinational aluminium producers with operations in Iceland. The crucial difference between these earlier instances however, and the recent incidents related to Samherji, Eimskip and Samskip is that the global operations of these companies are conducted from Iceland, not somewhere else. For further reading see for instance Saving Iceland, “Behind the Shining: Aluminum’s Dark Side,” 8 October 2007, savingiceland.org/2007/10/behind-the-shining-aluminums-darkside/ 3/ and Henry Chu, “Iceland Divided Over Aluminium’s Role in its Future,” Los Angeles Times, 26 March 2011, https://www.latimes.com/business/la-xpm-2011-mar-26-la-fi-iceland-economy-20110326-story.html.

45 I am indebted to Katrín Gunnarsdóttir for introducing me to this work.

46 Óskarsdóttir, Ásdís Helga. “Leiðin er innávið og uppímóti: Fjórða bylgja femínismans og íslenskar kvennabókmenntir.” In “Afsakið þetta smáræði!”, edited by Guðrún Steinþórsdóttir and Sigrún Margrét Guðmundsdóttir. Special issue, Ritið 2 (2022): 5–48.

47 Óskarsdóttir, “leiðin er innávið og uppímóti,” 19.

48 See for instance Pamela Hogan’s recent documentary The Day Iceland Stood Still (2024).

49 Dimitrakaki, “Art, Instituting, Feminism and the Common/s,” 5. For De Angelis’ definition of the commons fix see Massimo De Angelis, “Does Capital Need a Commons Fix?,” Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization 13, no. 3 (2013): 603–615.

50 My doctoral dissertation discusses the notion of an infrastructrual crisis in more detail, as does a recent article, where I introduce the notion of New “New Iceland” in Icelandic. See Marteinn Sindri Jónsson, “Nýja Nýja Ísland og innviðir skapandi greina.” Vísbending 43, no. 11 (2025): 40–41. https://visbending.is/tolublod/2025/11/.

51 New Iceland is curiously the name of a region on Lake Winnipeg in Manitoba founded by Icelandic settlers in 1875, early in Iceland’s largest wave of emigration (1870–1914) when 15,000 Icelanders, about 20% of the nation, emigrated to Brazil, Canada and the US.

52 Sjá for instance Mark Baker, “U.S.: Rumsfeld’s ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Europe Touches on Uneasy Divide.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, January 24, 2003. https://www.rferl.org/a/1102012.html.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

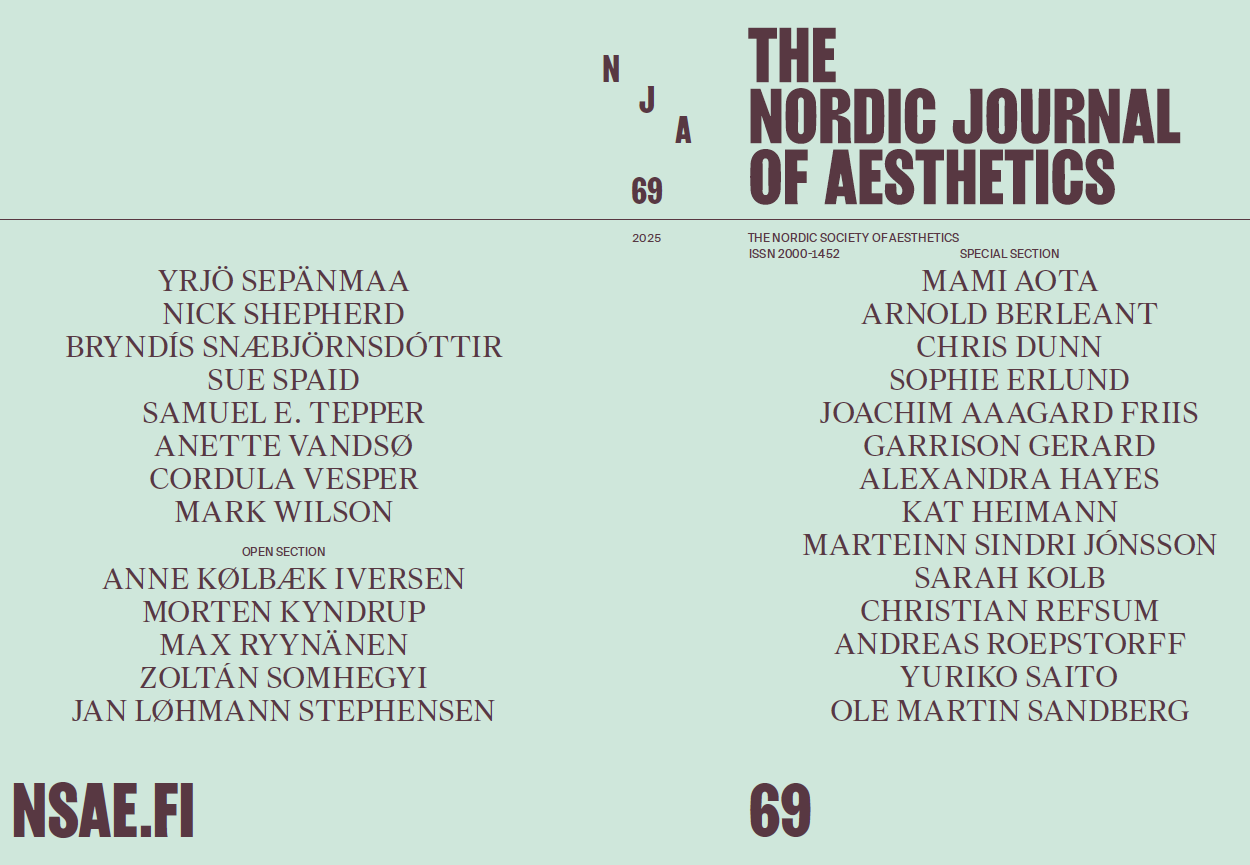

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Marteinn Sindri Jónsson

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See The Effect of Open Access).