Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Capturing love at a distance:

Multisensoriality in intimate video calls between migrant parents and their left-behind children

Yumei Gan

Shanghai Jiao Tong University

Abstract

Studies have shown that multisensorial interactions are an important medium for achieving love and intimacy. Nevertheless, the question remains: How do people constitute their “love at a distance” when they can only interact with each other over a video call, in which certain sensorial resources (e.g., touch, smell, and taste) are not available? Drawing from two years of video-based fieldwork involving recordings of habitual calls among the members of migrant families, I consider the application of Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis (EMCA)-informed video analysis to investigating intimate relationships constructed through remote means. I present an innovative method of video recording that allows me to analyze the interactional resources toward which participants orient themselves in their calls. I illustrate this approach with data analysis to demonstrate the relevance of video to examining intimacy at a distance. This article proposes that a distinct contribution of video-based research to the discipline lies in its ability to capture how people use their embodied and sensorial interactions to form intimacy across distances.

Keywords: video calls, intimacy, intimate relationships, video analysis, multisensoriality

1. Introduction

This article addresses the relevance of video analysis to investigating how people achieve intimacy at a distance. It introduces an intensive two-year, video-based fieldwork project that I conducted in Chinese migrant families. Through the detailed analysis of video-recorded calls between members of migrant families, this article shows that intimacy is mutually configured within the emergent organization of embodied and sensorial interactions. In particular, this article stems from the observation that when there is a lack of certain sensorial resources (e.g., touch), participants often mobilize and exaggerate their sensory reactions to maintain family closeness. Such observations, in turn, illustrate the utility of video, given the necessity for researchers to capture people’s interactions in real time.

The field site for this study is the homes of migrant families in China. With the influx of international and internal migration, distributed family constellations have become a significant feature of contemporary societies (Castle & Miller, 2003). More people are migrating to new destinations in order to seek out better paying jobs. In China, approximately 61 million children have parents working far from home, whom they only see once a year (ACWF, 2013). Consequently, their family lives are extensively transformed and reshaped during this time of separation. As Beck and Beck-Gernsheim remark, the family unit is no longer defined by living together under one roof or in a single location (2014, p. 14). Instead, “we inhabit a world in which our loved ones are often far away and those from whom we are distant may well be those dearest to us” (Beck & Beck-Gernsheim, 2014, p. 2, emphasis added).

Over the past three decades, a growing number of scholars, especially in the field of migration and family, have drawn attention to the impact of migration on family structures and relationships (Madianou & Miller, 2012; Parreñas, 2005). These studies have shown, on the one hand, that spatial separation between family members challenges people’s intimate relationships, and, on the other hand, that across considerable distance people still endeavor to maintain and develop intimacy. These latter studies have documented that the development of information and communication technologies (ICTs), such as those involved in video-mediated communication (VMC), has been significant in facilitating the experience of being a migrant and reshaping family closeness across time and distance. As these studies have shown, ICTs have allowed not only an increased frequency of contact but also a greater variety of communication, including wake-up calls, homework assistance, and immediate emotional support (e.g., Peng & Wong, 2016; Madianou, 2012).

Methodologically, existing studies on the use of ICT in migration settings have been mostly based on interviews––that is, participants’ accounts of their experiences of or their feelings about long-distance relationships (Longhurst, 2013; Madianou & Miller, 2012; Parreñas, 2005; Peng & Wong, 2016). While these studies have offered us insights into the challenges and possibilities of intimacy at a distance, they have not explored the situated interactional processes of achieving intimacy and love across distance. We thus know relatively little about how, for example, migrant parents and their children care for each other in real time. An exploration of migrant family practices in situ is necessary and valuable, as it will allow for the concrete discovery of the practices of “doing” (Morgan, 2011) migrant families and intimacy.

In this article, drawing on the compelling work done by Goodwin and Cekaite (2018) on the situated accomplishment of family intimacy and relationships, I adopt the view that intimacy is built through an interactional and multisensorial process. In order to examine how migrant family members constitute “distant love” (Beck & Beck-Gernsheim, 2014), it is therefore important to capture the situated interactional resources that participants orient themselves toward in the process of accomplishing intimacy and love, though the question remains: How can we (as the researchers) capture the distributed families’ “doing” of intimacy at a distance?

This article considers the application of qualitative video analysis (C. Goodwin, 1993; Heath et al., 2010) informed by ethnomethodology (EM) (Garfinkel, 1967) and conversation analysis (CA) (Sacks, 1992) to the challenge of investigating intimate relationships in migrant families. Based on two years of fieldwork in which I recorded routine video calls in Chinese migrant families, I introduce the relevance of audiovisual data to the study of intimacy in the lives of distributed families.

This article is divided into three main sections. First, I briefly revisit previous work on intimacy and multisensoriality in family lives. Second, I introduce my approach to video analysis and video-based fieldwork. Before discussing the practicalities of video recording, I describe some considerations relevant for researchers conducting fieldwork of intimate video calls in Chinese migrant families. Third, in scrutinizing the collected video data, I demonstrate that such data are beneficial for researchers analyzing intimacy because it is possible to observe how people in a particular setting invoke multisensorial and situated interactional resources in order to “do” intimacy. Most importantly, I show that the effort to achieve intimacy is displayed through the visible use of sensorial resources.

2. Background: Multisensoriality and intimacy in family lives

Social relationships, including intimate ones, are maintained through an interactional process wherein a sense of closeness develops in moment-by-moment interactions (Goffman, 1971; Mandelbaum, 2003; Pomerantz & Mandelbaum, 2005; Stivers, 2019). Studying the interplay between social interactions and social relationships has been an important concern for EMCA studies (Sacks, 1992; Schegloff, 2006). Previous CA studies have extensively investigated how people maintain relations in moment-by-moment evaluations of the materials of talk (e.g., Sacks et al., 1974; Schegloff, 1986). With the increasing use of video recording, scholars have more recently proposed an “embodied turn” (Nevile, 2015), which highlights the importance of embodied resources in unfolding interactions. In particular, pioneering researchers of video analysis, Goodwin (1981) and Heath (1986), have highlighted the role of gaze and body movement in coordinating interactions.

More recently, studies have uncovered the important role of senses in sustaining human relationships. This role has been mostly discussed in the emerging literature on the multimodal and multisensorial turn in interactional studies (Stivers & Sidnell, 2005; Meyer et al., 2017; Goodwin & Cekaite, 2018; Mondada, 2019). While “multimodality” has been used to refer to how people use multimodal resources, such as talk, gestures, gaze, body postures, and the physical environment, to accomplish social actions (Goodwin, 2000; Mondada, 2014, 2019), the analytical focus of “multisensoriality” “relies on” (Mondada, 2019, p. 60) a multimodal approach and highlights the role of human's senses in social interactions. Following the emergence of multisensoriality, scholars have argued that sensory bodies are not only resources for people to interact with each other but also practices used for sensing the world (Mondada, 2019, p. 47; see also a discussion in Mondada et al., 2021/this issue). That is, sensorial resources, such as taste, sound, and smell, can be instrumental to the accomplishment of actions. Furthermore, people can “make relevant the sensory features of these experiences for others, and share them intersubjectively, by collectively and jointly producing and coordinating them, and by publicly expressing, displaying, and witnessing them” (Mondada, 2019, p. 51).

Relevant to the present study, some EMCA investigations have uncovered the importance of the senses and multisensoriality in family lives. By examining the detailed practices of intimacy between family members, Goodwin and Cekaite (2018) have shown the importance of the multisensory body in building family solidarity and closeness. They demonstrate that intimacy encompasses not only talk but also an “embodied choreography” of prosody (e.g., pitch and voice quality) and the body (e.g., touch, eye gaze, and posture). For example, they provide fine-grained analysis on forms of bodily intertwining when family members coordinate and negotiate the accomplishment of activities. These intertwining entanglements unfold moment by moment and contribute to displays of intimacy and affection in family lives. These embodied and multisensorial practices allow each family to shape their own family habitus (Bourdieu, 1977) in the organization of mundane actions.

A growing body of literature draws attention to tactile arrangements in intimate relationships, such as interactions between parents and children (de León, 1998; Cekaite, 2010; Cekaite & Holm, 2017; M. H. Goodwin, 2017; M. H. Goodwin & Cekaite, 2018; Katila, 2018). On the one hand, studies have shown that touch is an essential resource mobilized by parents to “control” or “socialize” their children. For example, Cekaite (2010) shows how touch can be used to “shepherd” children or to “upgrade” directives to achieve compliance (cf. M. H. Goodwin & Cekaite, 2013). On the other hand, some studies are concerned with touch and care, attachment, bonding, and intimacy. For instance, M. H. Goodwin (2017) articulates that families make use of “culturally appropriate tactile communication” (such as hugging and kissing) to achieve moments of affectively intimate exchanges. She terms the co-engagement of bodies as the “intimate haptic sociality” through which participants sequentially orchestrate joint participation in their affective lives.

However, given the importance of the senses in negotiating and developing intimacy, what happens if certain senses are not available for people in remote interactions? For example, in situations of family separation wherein family members cannot touch each other physically, how do they constitute an intimate interaction? How do they display care for each other? I investigate these questions by exploring real-life interactions between migrant family members. Based on the data-driven analysis of intimate video calls between migrant parents and their children, I will show that video calls form a “perspicuous setting” (Garfinkel, 2002, pp. 181-182) in which to investigate the senses, as participants themselves often make their senses visible and accountable (Mondada et al., 2021/this issue) for remote parties.

3. Video-based fieldwork: Video recording intimate video calls in Chinese migrant families

China has witnessed massive rural-to-urban migration since the economic reforms of 1978 (Ye, 2011). However, due to a variety of reasons, migrant workers sometimes cannot bring their children to their city of work (Ye & Pan, 2011). This fact has resulted in the emergence of the phenomenon of left-behind children, who are often brought up in rural areas by grandparents (Santos & Harrell, 2017). The phenomenon has been widely reported in both popular media and academic literature.

My research project with this population aims to assess how parents and their children care for each other when they live far apart. For this purpose, I first build on studies in the area of migration and new media. These studies have revealed that the emergence of ICTs facilitates the experience of long-distance family ties. As Katz and Aakhus (2002) put it, contemporary forms of media and technologies allow migrant families to be in “perpetual contact” with one another. A similar growing body of literature draws attention to VMC technologies. These studies have shown that video calls (e.g., Skype and FaceTime) deliver a form of connected presence (Licoppe, 2014) that could be described as “live,” “real time,” “streaming,” and “immediate” (Madianou & Miller, 2012). The possibility of seeing and being seen in video calls has revolutionized the sense of connection among distant family members.

In order to study such video calls in Chinese migrant families, I adopt the methodology of qualitative video analysis (C. Goodwin, 1993; Heath et al., 2010) informed by EM and CA. Qualitative video analysis is an inductive methodology utilizing recordings of naturally occurring activities and interactions. The approach aims to study in minute detail the temporal and sequential structure of interaction and the ways social actions are accomplished in situ. The advantages of working with video-recorded data are manifold. It allows analysts to study the full range of resources involved in social action (e.g., gaze, gesture, and body orientation). Also, video recordings document interactional practices that happen in such a quick and fleeting manner that they evade written description. Recordings can be replayed repeatedly, sometimes in slow motion, to investigate a particular moment in detail (Sacks, 1984). I also draw on existing EMCA studies of video conferencing in various settings (e.g., Licoppe & Morel, 2012; Licoppe, 2017; Mondada, 2010; Raudaskoski, 2000), which have employed the method of video recording.

3.1 Challenges for video-based research on intimate video calls

Conducting video-based fieldwork among Chinese migrant families, however, presents some new challenges. For example, how can researchers gain access to the private and intimate home setting where family video calls normally take place? How can researchers set up their cameras in order to capture mobility (Haddington et al., 2013; Mcllvenny et al., 2009; Smith, 2021/this issue), since people in this setting are using mobile devices (such as smartphones rather than laptops) for video calls?

3.1.1 A private setting: Intimate family lives

Scholarly interest in VMC technologies has expanded since the 1990s (see also the excellent review of studies on VMC by Mlynář et al., 2018). The first wave of research focusing on the interactional practices of VMC was dominant in studies of video conferencing in workplaces and businesses (e.g., Heath & Luff, 1992; Mondada, 2004; Licoppe & Dumoulin, 2007; Raudaskoski, 2000). Subsequently, a new scholarly turn surfaced as technological development increased. When technologies become ubiquitous within the home, research followed the trend by moving beyond work settings to investigate the use of technology in domestic settings, such as video calls at home between family and friends (e.g., de Fornel, 1994; Crabtree et al., 2003; Relieu, 2007; Licoppe & Morel, 2012; Licoppe, 2017; Sunakawa, 2012). However, there exist significant challenges for the video recording of such calls in intimate settings. For example, it is more difficult to recruit participants to be video recorded than it is to recruit them for less committed forms of participation, such as interviews. Video recording in the domestic environment introduces sensitivities due to its private nature (Heath et al., 2010, p. 15). Securing participants’ permission to video record their private lives thus becomes a challenging initial mission for researchers.

3.1.2 A mobile setting: Mobility of the device and young children

Many existing studies on video calls have focused on calls made with stationary devices, such as a desktop computer (e.g., Ames et al., 2010). When conducting video calls with a stationary computer, participants normally arrange themselves in front of the camera (Ames et al., 2010, p. 150). As a result, researchers can set up their own camera in front of the device in order to record interactions during the video call. However, in most Chinese migrant families, people use mobile video calling technologies, rather than those found on a laptop or desktop. Most of my participants’ families do not have a computer, instead using smartphones, as they are affordable (Fieldnote, 26 October 2016; see also Oreglia & Kaya, 2012). The setting is therefore a mobile one, in which researchers are expected to capture mobility. What is more, there are two dimensions of such mobility in these calls: (a) mobility of the smartphone and (b) mobility of the young children. For the former, in some cases, participants hold their smartphones and walk around while they are talking. For the latter, what often happens in these video calls is that young children do not stay near the smartphone for the duration of the call. They frequently move around in the room (e.g., to play with a toy). Consequently, the adults who are holding the phone do not remain stationary either, but often walk around to follow the children (see the discussion on mobility in Gan et al., 2020, p. 2).

Recording and studying mobility in interaction has been a challenging issue. A number of previous interactional studies on family lives have drawn on research data collected in relatively immobile settings, such as the dinner table. Dinner tables were a popular site for scholars not only because of the interaction itself but also because these are stable and easily recordable loci (Searles, 2018a, p. 14). However, over the past decade, a growing body of interactional literature has discussed why and how to record interaction-in-mobility (see the review in Mcllvenny et al., 2009) in order to understand interaction in complex, multimodal environments and spaces. In my video-based fieldwork, both the device and the participants are mobile: therefore, finding a method to record them in interaction becomes a practical challenge.

3.2 Responding to challenges: An innovative method for video recording

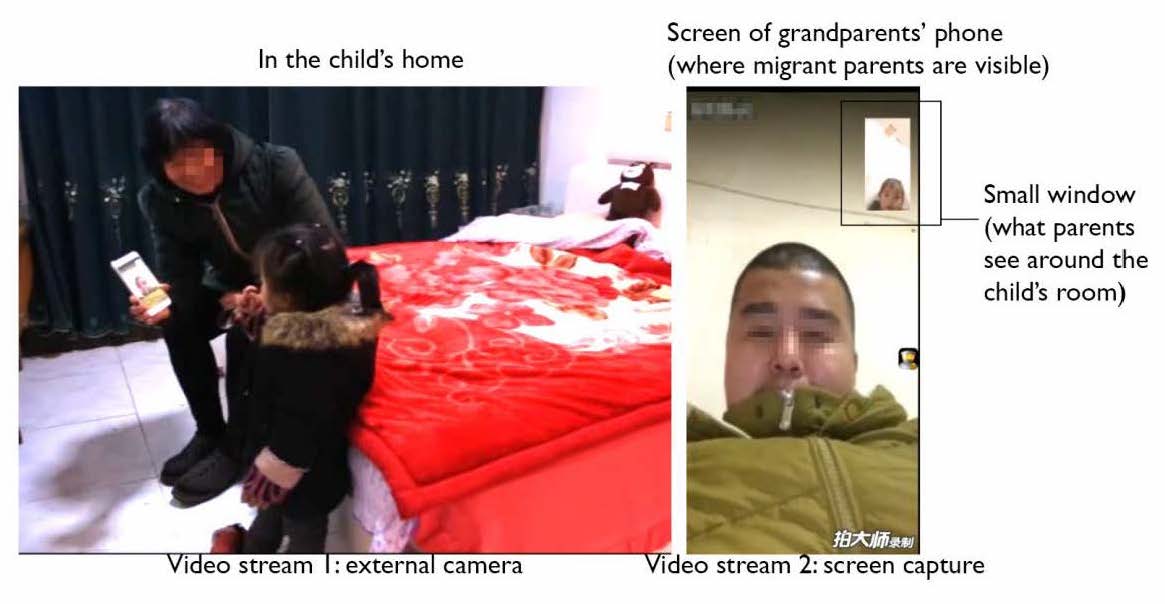

The challenges of privacy and mobility place constraints on how such intimate video calls can be investigated. Gathering data under these conditions demands that researchers deal with such difficulties while also capturing the unique ways in which participants orient themselves within these settings. Accordingly, I developed an innovative method that combines the use of an external camera within the home of the young children with a screen capture of grandparents’ phones to record all participants in the interaction (see below, Figure 1).

Figure 1: Method of video recording

As seen in the image on the left in Figure 1, I placed an external camera (GoPro) in the child’s home so that I could capture the interactions between the grandparents and children around the smartphone. Then, I installed a screen capturing app (Pai Da Shi for Android phones, Apowersoft for iPhones) on the grandparents’ phones so that I could gain the perspective of the migrant parents that were visible on the screen (the image on the right in Figure 1). From the very small window in the right corner of the screen capture, I also have access to what the migrant parents can see of the family and home on their screens.

Combining multiple camera views is by no means my own innovation. It has been a common practice in video-based research, since multiple views can be of value for researchers, allowing them to explore the detailed coordination of actions (see also the discussion of multiple cameras in Hindmarsh & Llewellyn, 2018, p. 418). However, previous video-based studies of VMC have mostly used participants’ self-recording of their video calls on laptops as data (e.g., Licoppe & Morel, 2012; Searles, 2018b), while other studies used an external camera to capture interactions in front of the computer (e.g., Sunakawa, 2012). Few scholars have combined the two views. The combination of the two video streams allows me to not only capture all participants in the interactions (including grandparents, children, and migrant parents) but also to observe the interactions both in front of the device and in the device, which responds to the issue of mobility.

In total, I recorded 55 naturally occurring video calls in 45 migrant families over two years. The field site was in the Sichuan province in China (the language of the data is the Sichuan dialect). In those families, both the father and the mother of the children were migrant workers. Children were under three years old. The choice of the children’s age was made based on previous migration literature in which scholars mention that families with very young children prefer to use video calls (e.g., Madianou & Miller, 2012, p. 118; Peng & Wong, 2016, pp. 214-215).

I also adopted several practical solutions to address challenges that emerged in the actual video recording process. These challenges required a variety of social and technical adjustments, from minimizing the impact of my presence to hiding the camera from a child participant. Obviously, my presence (as a researcher) in the room may have had an impact on how the participants interacted. In order to reduce this influence, I visited the participants’ homes several times (see also the similar strategy used by Goodwin & Cekaite, 2018) before recording. This step ensured—as much as possible—that participants were accustomed to my presence and conducted their video calls more naturally, which allowed me to obtain data “not produced for the benefit of, or solicited and arranged by, researchers” (Cekaite, 2020, p. 84). I also chose to use a small external camera (GoPro) rather than big cameras (for instance, I used a Canon XF105 camcorder in the exploratory stage of the fieldwork) in order to reduce the influence of the camera on the attention of the young children. These steps, such as building trust with the participants and choosing appropriate camera devices, enabled me to respond to the distinctive features of conducting video-based fieldwork in an intimate and mobile setting.

4. Analysis: Senses in video calls and intimate relationships

One distinctive feature of VMC (in general) is that it takes place in a more constrained setting than face-to-face interaction. In video calls, certain multisensorial resources are not available for participants. For example, people cannot touch each other, and they cannot smell or taste a remote party’s food. As previously mentioned, existing research has shown the importance of sensory experiences, in particular touch, in maintaining intimate relationships; therefore, video calls would seem to be a challenging site for participants to achieve intimacy. However, in this analysis, I use the data to illustrate that people still mobilize and even exaggerate their sensorial experience in a mediated environment in order to form intimacy. The analysis focuses on how participants orient themselves toward senses and sensorial actions to accomplish a remote family relationship even though they are in a space where tactile, olfactory, and gustatory senses are not available to share. In particular, the analysis will show how senses and sensorial resources are “invoked, moved, noticed and touched” (Hindmarsh & Llewellyn, 2018, p. 418) and then become visible and relevant for interactants themselves. The analysis, in turn, reflects the methodological benefit of combining two video streams. The recording method allowed the researcher to observe the local ecologies of participants’ orientation to sensorial modalities in the course of VMC. In the following two examples, I invite the reader to observe how people display and sometimes make use of their senses in the building of their intimate relationships across distance, as well as how my method of video recording allows such an analysis.

4.1 Sharing food in video calls

In Extract 1, when a remote mother is eating noodles, her children on the other end of the video call ask to eat the noodles. Although people cannot physically reach and eat noodles over a video call, both the children and their migrant parent playfully request and offer the noodles. In so doing, they share a moment of family mealtime together.

Extract 1

Open in a separate windowAt the beginning of Extract 1, when the mom is eating noodles, her son, labeled as “BOY” in the transcript, sticks out his tongue (Figure 2a). He produces a smiling face and presents it in the center of the phone screen (the right image in Figure 2a). The mom sees the child’s face (see the mom’s gaze in Figure 2a). Then she moves her phone camera to show more of her noodle bowl. In line 04, the mom invites the remote parties to join her activity of eating. She says, “watch me eat noodles, hah-hah-hah.” She formulates this with an imperative verb and audible laughter. As Glenn and Holt (2015, p. 2) argue, laughter’s position in relation to talk can be important in determining the nature of its contribution. Here, the mother’s production of laughter at the end of a turn marks it as something joyful. Furthermore, this invitation to “watch” her eat noodles not only makes the eating an available scene for remote members to view but also creates a shared moment between her and her children around the food. In this situated moment, it is not solely the mother eating noodles. It now becomes a joint activity in which the mom is eating and her children are watching.

Then, the boy shows his tongue, and further produces extended, non-lexical vocalization sounds––“NAH-nah-nah-nah”––by biting his tongue (line 05 and Figure 2b). This vocalization is produced with an onset high and then a lowering intonation. The “NAH-nah-nah-nah” is nicely in line with what Wiggins (2002) describes as a “gustatory expression” of pleasure. As Wiggins points out, while food and eating have often been conceptualized as internal and private events, it is observed that people produce the eating activity interactionally. Importantly, the gustatory pleasure is sequentially organized and oriented to other speakers’ turns. As shown, while the boy is making noise, he keeps his face and mouth available on the screen so that his mom can see him (Figure 2b). His embodied displays and use of a different intonation to produce this vocalization not only brings the pleasure of “fake eating” to the talk but also performs an embodied request to eat the mom’s noodle.

Although the boy displays his tongue and keeps his mouth open for a time on the screen, the mom does not share the noodles with him. When the interaction continues, in line 09, the boy requests the chance to eat by employing a declarative request form: I want X. He says, “I want to eat” (wo yao chi). Wootton (1981) shows that when children’s requests are not granted, they often use the format “I want X” to pursue the request. In this case, the boy uses “I want to eat” to produce a more explicit request. Grandmother treats the boy’s request as being related to the taste of the noodle. She comments, “watching her eat, it looks delicious?” (kandao ta chi de duo an yi, ga?) (line 10). Then in line 11, the boy further pursues his request. He uses a louder voice with some emphasis on the final syllable, “I want to EAT!” (wo yao CHI!). Then the girl (the boy’s sister) starts to mimic her brother’s request. She joins by repeating the request at a fast pace in line 13, “>I want to eat<, >I want to eat<” (>wo yao chi<, >wo yao chi<). Mom responds after the girl’s request. She “feeds” her noodle to the phone screen (Figure 2c). As seen in Figure 2c, the noodles are presented to the camera. The boy opens his mouth and produces an exaggerated eating sound, “AOOO” (Figure 1d). The “AOOO,” similar to the previous “NAH-nah-nah-nah” (line 05), is a non-lexical vocalization with which the boy mimics the sensorial event of eating and makes audible the pleasure of the experience.

In face-to-face family interactions, parents and children are able to share their bodies as well as the multisensory world (Goodwin & Cekaite, 2018). In the situation of a video call, we still see that people orient themselves toward and employ their sensory bodies to achieve a moment of virtual sharing. The boy orchestrates the talk (lexical and non-lexical), the body (leaning into the camera, displaying a smiling face on the screen), and voice quality to request noodles from his mom. In turn, the mom offers the noodles to her children by visibly holding the noodles up to phone camera. The girl, who mimics her brother, also shares a playful engagement in the multisensorial scene of pretending to eat. These details allow us to see how participants have a virtual food sharing moment by “embodying the experience” (Wiggins, 2002, p. 328) of eating. Even in a constrained setting, people treat mutual participation as something embodied and sensorial. They mobilize particular senses and use them in an exaggerated way (e.g., the opening of the mouth in an exaggerated manner for a visual display of eating and the production of noises for an audible display) to cope with the constraints placed on that sense. Most interestingly, the participants turn the missing physical connection into a playful and joyful “as if” situation of shared copresence. They use what is visible on the screen (i.e. technological affordance) and the resources available to them (e.g., sensory body) to achieve this act.

Based on this extract, I wish to point out the value of combining two video streams from the data collection in the analysis. This methodology is beneficial because it provides researchers with the resources to understand the situated ecologies of interactions at a distance. Figure 3 below depicts some local ecologies of sharing food in video calls in which parents and children are filled with the sensations of others’ food in a virtual space (3a: sharing meat; 3b: sharing candy; 3c: sharing noodles). From these images, we can see that feeding can be initiated or requested by either the parents or the children. The reader can easily observe the participation involved in the process of sharing food. For example, on the left, researchers can scrutinize the scene as the grandparents (who are holding the phone but are not visible on the phone screen) affectively participate in pretend eating moments. They smile (3a, 3c), or they lean into the child and phone to join the family moment (3b). On the right (captured from the smartphone screen), it is possible for researchers to analyze how migrant parents initiate or react to such intimate activities. Their facial expressions (e.g., both dad and mom are smiling) and their artful manipulation of objects (e.g., placing the noodles in front of the camera) are publicly displayed on the screen for the remote parties and subsequently made visible for researchers’ analysis.

Figure 3: Local ecologies of sharing food in video calls

4.2 Kissing remote parents over the phone

Another example of the multisensorial achievement of intimacy in video calls is kissing. M. H. Goodwin (2017) reveals that kisses are affectively rich and supportive family rituals. She argues that kisses, like other forms of haptic actions (e.g., hugs, taps), are embodied displays of love that are often modulated to express heightened intimacy. I observe in my dataset of Chinese video calls that kisses are also requested or instructed. While kissing (in a face-to-face setting) is typically mutually felt, participants orient themselves toward the use of their sensory bodies to accomplish a kiss and achieve similar intimacy at a distance. In Extract 2, the grandma (GRA) instructs both the boy and the girl to kiss their parents over the phone.

Extract 2

Open in a separate windowAt the beginning of this extract, the grandmother initiates an instruction. Her instruction is not for the benefit of herself; she is encouraging an interactional sequence between the two children and their parents. The grandmother says, “two siblings come on kiss both your dad and mom” (line 01). While doing so, she points in the direction of the phone. When she does not receive a response (see the gap in line 02), the grandmother pursues the children’s display of kisses. She prompts the children again, “kiss kiss” (qin yi kou) (line 03). While this directive is addressed to both the boy and the girl, the girl responds to the directive more promptly, as seen in line 04.

In line 04, the girl stands up from her chair and walks toward the phone. She leans her face into the screen and physically kisses the mobile phone screen (as we can see from the small window on the right view in Figure 4b, the girl’s lips touch the screen). The grandmother comments on the girl’s kisses with an exclamation, “awww” (ei ya) (line 05). On the other end of the call, the mom smiles. She also gives the same compliment as grandmother does, by stating “awww” (ei ya) (line 06). After that, the boy also stands up and leans his body into the phone. In Figure 4c, the boy bends the upper part of his body and puts his lips on the screen. He thus also kisses his parents over the phone by physically kissing the phone. Again, the mom produces the same compliment, “awww” (ei ya) (line 08), in response to “receiving” the boy’s kiss.

Kissing is often taken as an intimate gesture of love, but because of its private nature, kissing seems difficult to record and to study (Frijhoff, 1991). In video recording these intimate video calls, researchers have the opportunity of accessing such intimate acts within a family’s life. This extract allows us to observe how a kiss is instructed and then performed through embodied, linguistic, and sensorial resources. While face-to-face kissing can be mutually felt, the kiss in the video call was expressed and received through other sensorial displays. First, the children’s kisses are produced through displays of physical actions. They kiss and perform their kisses by coordinating the physical smartphone with their body and face; they position their body and create a sensorial ecology where they lower their body, cock their mouth over the phone. Second, the kisses are received––or rather, seem to be received––by the remote parents. The parents on the phone receive the kisses through audible compliments and commentaries, as well as sentimental facial expressions. The sensorial production and receipt of the kiss therefore allow the participants to highlight the visual and audible displays. In turn, such displays lead the other party to see and feel a remote sensorial experience and a remote intimate gesture.

Again, the technical combination of two video streams allows me to observe the kisses in video calls from both sides. In the local ecologies of kisses (see Figure 5), children and parents are affectively as well as physically engaged in virtual kisses with each other. For example, in Figure 5a and 5c, the child physically moves the phone to his lips and kisses his parents over the phone. Such actions connect materials (here, the phone) to a display of affection. The physical kisses over the phone make the mediated presence fundamentally socio-material (Hindmarsh & Llewellyn, 2018). As Hindmarsh and Llewellyn (2018, p. 431) describe, material objects are not independent from their social uses. That is, the object and interactions are intertwined and made visible by people in order to accomplish and achieve social actions. As a result, in Figure 5b and 5d, we observe the procedural accomplishment of a computer-generated kiss over the phone. Furthermore, the left side of the video recordings allows me to observe how a kiss is produced and received through sensory bodies. In 5b, the boy prepares his lips before he actually reaches the phone. In 5d, the mom forms the kisses in the air rather than physically touching the screen, but she loudly kisses her daughter by making a sensorial sound. The intimacy of long-distance family routines is then intensified through the use of multiple signs of affective attunement (e.g., kisses or other gestures used to display affection), combining a series of verbal and multisensorial actions.

Figure 5: Local ecologies of kissing in video calls

5. Discussion

Love and intimacy play a central role in human experiences. However, because of the private nature of intimate relationships, there is a methodological challenge for researchers in recording and studying them. This article presents the application of qualitative video analysis to address the challenge of investigating intimacy in video calls in Chinese migrant families. I describe a combination of multiple camera views that provides the researcher with audio-visual access to analyze the interactional and sensorial resources used by participants. I provide two analytical examples in which people mobilize their senses and bodies in a mediated environment as they achieve intimacy with remote parties.

The use of an EMCA-informed video analysis approach to studying intimate calls in migrant families makes unique contributions to the investigation of migration and new media. While existing studies have provided important insights into understanding the role of ICTs and VMC in migrant families in both a transnational and internal migration context, they have not explored how people conduct video calls. It is also difficult for participants to remember the details of what happens in a call. As a result, what is missing from the literature is the actual communicative practice of the calls and the actual usage of the technologies, including “the interactional mechanics of it, even the interactional processes of scheduling these calls, getting everyone ready for them” (Harper et al., 2017, p. 304). This article documents a methodological attempt and innovation to investigating actual communication and the practices involved in “doing” family (Morgan, 2011) across distance. The video recordings of these intimate calls allow me to address forms of family practices through which family life is accomplished and sustained in a virtual space. The value of this approach is that researchers get access to the “full palette of resources” (Goodwin & Cekaite, 2018, p. 258) that participants themselves make use of. By looking at the interactive process, I show how participants orient themselves toward distributed family life as embodied, multisensory, and material. Participants’ orientations toward sensorial resources me to observe how intimacy is manifested through the interpersonal features of talk and the body. In particular, we observe that people display the ability to accomplish sensory work in a constrained environment and, in doing so, orient toward maintaining their intimate relationships.

Furthermore, this article has implications for EMCA-informed studies of VMC. First, I describe the advantage of combining two camera views in exploring video calls, through which the researcher can access the local ecologies of intimate activities. This recording technique allows the researcher to observe the artful production of events behind the scenes. Second, previous EMCA research on video calls has mainly focused on (1) specific actions in video calls, such as showing an object or an environment, checking technology, or camera movements (Mondada, 2007; Licoppe, 2017; Searles, 2018b) and (2) specific phases during a call (e.g., setting up, opening, closing) (Bonu, 2007; Licoppe, 2012; Licoppe & Morel, 2012; Mondada, 2015). While these studies have provided important and insightful findings regarding particular interactional and technological features of video-mediated interactions, there is still a paucity of investigations into how multimodal and multisensorial interactions in a mediated place intertwine with human relationships. Here, my interest complements these previous studies, as I am concerned with how mediated interactions contribute to members’ engagements with intimacy. In the current world, VMC has become a valuable apparatus for long-distance relationships. Further work on VMC and intimacy would thus shed light on the dynamics of practices of intimacy in a mediated and constrained world.

Acknowledgements

My heartfelt gratitude goes to all the families who allowed me to visit their homes and record their intimate video calls. Without their trust and support, this research would not have been possible. I also benefited from various delightful discussions with Sara Goico, Julia Katila, and Candy Goodwin on multisensoriality and intimacy. I am grateful to Adrienne Isaac and David Edmonds for reading an earlier version of the paper and giving me valuable comments. This manuscript was completed when I was a Fulbright Fellow at the Center for Language, Interaction, and Culture (CLIC) at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) (2019–2020).

References

ACWF (All China Women’s Federation). (2013). Research report on the situation of rural left-behind China, rural-urban migration children in China [In Chinese]. Zhong Guo Fu Yun (Chinese Women’s Movement), 6, 30–34.

Ames, M. G., Go, J., Kaye, J. ‘Jofish’, & Spasojevic, M. (2010). Making love in the network closet: The benefits and work of family videochat. Proceedings of the 2010 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 145–154. New York, USA: ACM.

Beck, U., & Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2014). Distant Love: Personal Life in the Global Age. Cambridge: Polity.

Bonu, B. (2007). Connexion continue et interaction ouverte en réunion visiophonique. Reseaux, 144(5), 25–57.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice (R. Nice Trans.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Castle, S., & Miller, M. J. (2003). The Age of Migration. Nueva York, Guilford.

Cekaite, A. (2010). Shepherding the child: Embodied directive sequences in parent–child interactions. Text & Talk, 30(1), 1–25.

Cekaite, A. (2018). Intimate Skin-To-Skin Touch in Social Encounters: Lamination of Embodied Intertwinings. In Favareau, D. (Ed.) Co-operative Engagements in Intertwined Semiosis: Essays in Honour of Charles Goodwin (pp. 37–41). Tartu: University of Tartu Press.

Cekaite, C. (2020). Ethnomethodological approaches, In Vannini, P. (Ed.) The Routledge International Handbook of Ethnographic Film and Video (pp. 83-94). Oxon, OX: Routledge.

Cekaite, A., & Kvist Holm, M. (2017). The Comforting Touch: Tactile Intimacy and Talk in Managing Children’s Distress. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 50(2), 109–127.

Crabtree, A., Hemmings, T., Rodden, T., Bb, N. N., Cheverst, K., Clarke, K., & Hughes, J. (2003). Designing with care: Adapting cultural probes to inform design in sensitive settings. Ergonomics Society of Australia, 4–13.

de Fornel, M. (1994). Le cadre interactionnel de l’échange visiophonique. Réseaux, 12(64), 107–132.

de León, L. (1998). The Emergent Participant: Interactive Patterns in the Socialization of Tzotzil (Mayan) Infants. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 8(2), 131–161.

Frijhoff, W. T. M. (1991). The kiss sacred and profane: Reflections on a cross-cultural confrontation. In Bremmer, J., & Roodenburg, H. (Eds.) A Cultural History of Gesture from Antiquity to the Present Day: With an Introduction by Sir Keith Thomas (pp. 210–236). Polity Press.

Gan, Y., Greiffenhagen, C., & Reeves, S. (2020). Connecting Distributed Families: Camera Work for Three-party Mobile Video Calls. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–12. New York, USA: ACM.

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in Ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Garfinkel, H. (2002). Ethnomethodology’s Program: Working Out Durkheim’s Aphorism. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Glenn, P., & Holt, E. (2015). Laughter. In Tracy, K., Ilie, C., & Sandel, T. (Eds). The International Encyclopedia of Language and Social Interaction (pp. 1-6). JohnWiley & Sons.

Goffman, E. (1971). Relations in Public: Microstudies of the Public Order. New York: Harper & Row.

Goodwin, C. (1993). Recording human interaction in natural settings. Pragmatics: International Pragmatics Association, 3(2), 181–209.

Goodwin, C., (2000). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 32, 1489-1522.

Goodwin, M. H. (2017). Haptic Sociality: The Embodied Interactive Constitution of Intimacy Through Touch. In Heath, C., Streeck, J., & Jordan, S. (Eds.) Intercorporeality: Emerging Socialities in Interaction (pp. 73–102). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goodwin, M. H., & Cekaite, A. (2013). Calibration in directive/response sequences in family interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 46(1), 122–138.

Haddington, P., Mondada, L., & Nevile, M. (Eds.). (2013). Interaction and Mobility: Language and the Body in Motion. Berlin, Germany: Walter de gruyter.

Heath, C., Hindmarsh, J., & Luff, P. (2010). Video in Qualitative Research. Sage.

Heath, C., & Luff, P. (1992). Media Space and Communicative Asymmetries: Preliminary Observations of Video-Mediated Interaction. Human–Computer Interaction, 7(3), 315–346.

Hindmarsh, J., & Llewellyn, N. (2018). Video in Sociomaterial Investigations: A Solution to the Problem of Relevance for Organizational Research. Organizational Research Methods, 21(2), 412–437.

Katila, J. (2018). Touch between child and mother as an affective practice. In Juvonen T. & Kolehmainen,M. (Eds.) Affective Inequalities in Intimate Relationships. Routledge.

Katz, J. E., & Aakhus, M. (2002). Perpetual Contact: Mobile Communication, Private Talk, Public Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kinnunen, T., & Kolehmainen, M. (2019). Touch and Affect: Analysing the Archive of Touch Biographies. Body & Society, 25(1), 29–56.

Licoppe, C. (2004). ‘Connected’ Presence: The Emergence of a New Repertoire for Managing Social Relationships in a Changing Communication Technoscape. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 22(1), 135–156.

Licoppe, C. (2012). Understanding mediated appearances and their proliferation: The case of the phone rings and the ‘crisis of the summons’. New Media & Society, 14(7), 1073–1091.

Licoppe, C. (2017). Skype appearances, multiple greetings and ‘coucou’: The sequential organization of video-mediated conversation openings. Pragmatics, 27(3), 351–386.

Licoppe, C., & Dumoulin, L. (2007). L’ouverture des procès à distance par visioconférence. Reseaux, 144(5), 103–140.

Licoppe, C., & Morel, J. (2012). Video-in-Interaction: “Talking Heads” and the Multimodal Organization of Mobile and Skype Video Calls. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 45(4), 399–429.

Longhurst, R. (2013). Using Skype to mother: Bodies, emotions, visuality, and screens. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 31(4), 664–679.

Madianou, M., & Miller, D. (2012). Migration and New Media: Transnational Families and Polymedia. London: Routledge.

Mandelbaum, J. (2003). Interactive methods for constructing relationships. In Glenn, P. LeBaron, C. D., & Mandelbaum, J. (Eds.) Studies in Language and Social Interaction: In Honor of Robert Hopper (pp. 207–219). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

McIlvenny, P., Broth, M., & Haddington, P. (2009). Communicating place, space and mobility. Journal of Pragmatics, 10(41), 1879-1886.

Meyer, C., Streeck, J., & Jordan, S. J. (2017). Intercorporeality: Emerging Socialities in Interaction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mlynář, J., González-Martínez, E., & Lalanne, D. (2018). Situated Organization of Video-Mediated Interaction: A Review of Ethnomethodological and Conversation Analytic Studies. Interacting with Computers, 30(2), 73–84.

Mondada, L. (2004). Téléchirurgie et nouvelles pratiques professionnelles: Les enjeux interactionnels d’opérations chirurgicales réalisées par visioconférence. Sciences Sociales et Santé, 22(1), 95–126.

Mondada, L. (2007). Imbrications de la technologie et de l’ordre interactionnel. Reseaux, 144(5), 141–182.

Mondada, L., (2014). The local constitution of multimodal resources for social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 65, 137-156.

Mondada, L. (2015). Ouverture et préouverture des réunions visiophoniques. Reseaux, 194(6), 39–84.

Mondada, L. (2019). Contemporary issues in conversation analysis: Embodiment and materiality, multimodality and multisensoriality in social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 145, 47–62.

Mondada, L., Bouaouina, S., Camus, L., Gauthier, G., Svensson, H., Tekin, B. (2021). The local and filmed accountability of sensorial practices: The intersubjectivity of touch as an interactional achievement. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 4(3).

Morgan, D. H. G. (2011). Locating ‘Family Practices’: Sociological Research Online, 16(4), 174-182.

Nevile, M. (2015). The embodied turn in research on language and social interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 48(2), 121-151.

Oreglia, E., & Kaye, J. J. (2012). A gift from the city: Mobile phones in rural China. In Proceedings of the ACM 2012 conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (pp. 137-146). New York: ACM.

Parreñas, R. (2005). Long distance intimacy: Class, gender and intergenerational relations between mothers and children in Filipino transnational families. Global Networks, 5(4), 317–336.

Peng, Y., & Wong, O. M. H. (2016). Who Takes Care of My Left-Behind Children? Migrant Mothers and Caregivers in Transnational Child Care. Journal of Family Issues, 37(14), 2021–2044.

Pomerantz, A., & Mandelbaum, J. (2005). Conversation analytic approaches to the relevance and uses of relationship categories in interaction. In Fitch K. L. & Sanders, R. E. (Eds.,) Handbook of Language and Social Interaction (pp. 149–171). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Raudaskoski, P. (2000). The use of communicative resources in internet video conferencing. In Pemberton, L., & Shurville, S. (Eds.) Words on the Web: Computer Mediated Communication(pp. 44-62). Exeter, UK: Intellect Books.

Relieu, M. (2007). La téléprésence, ou l’autre visiophonie. Réseaux, 144, 183–224.

Sacks, H. (1984). Notes on methodology. In Atkinson, J. M., & Heritage, J. (Eds.), Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis (pp. 21–27). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures on Conversation. Oxford: Blackwell.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A Simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696–735.

Santos, G., & Harrell, S. (2017). Transforming Patriarchy: Chinese Families in the Twenty-First Century. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Schegloff, E. A. (1986). The routine as achievement. Human Studies, 9(2), 111-151.

Searles, D. K. (2018a). Building Family: The Interactional Practices of Families with Young Children. New Jersey, USA: Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey [PhD Thesis].

Searles, D. K. (2018b). ‘Look it Daddy’: Shows in family Facetime calls. Research on Children and Social Interaction, 2(1), 98–119.

Smith, M. (2021). Occupying and Projecting Participant Perspectives in Open, Unstructured Spaces. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 4(3).

Stivers, T. (2019). How We Manage Social Relationships Through Answers to Questions: The Case of Interjections. Discourse Processes, 56(3), 191–209.

Stivers, T., & Sidnell, J. (2005). Introduction: Multimodal interaction. Semiotica, 156, 1–20.

Sunakawa, C. (2012). Virtual “Ie” Household: Transnational Family Interactions in Japan and the United States. The University of Texas at Austin [PhD Thesis].

Wiggins, S. (2002). Talking with your mouth full: Gustatory mmms and the embodiment of pleasure. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 35(3), 311-336.

Wootton, A. J. (1981). Two request forms of four year olds. Journal of Pragmatics, 5(6), 511–523.

Ye, J. (2011). Left-behind children: The social price of China’s economic boom. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(3), 613–650.

Ye, J., & Pan, L. (2011). Differentiated childhoods: Impacts of rural labor migration on left-behind children in China. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(2), 355–377.