Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Balancing research goals and community expectations:

The affordances of body cameras and participant observation in the study of wildlife conservation

Rosalie Edmonds

University of California, Los Angeles

Abstract

This article explores the possibilities that arise from combining participant observation with body camera recording, through the analysis of the use of a GoPro to study communication at a Cameroonian wildlife sanctuary. The original goal of this research project was to use both video recording and participant observation as separate methodologies in order to understand how Cameroonian animal keepers and European volunteers at the Limbe Wildlife Centre worked across linguistic and ideological barriers to rehabilitate chimpanzees. However, increased participant observation became necessary due both to research participants’ expectations that the researcher contribute to daily work activities, as well as the logistical difficulties of recording highly-mobile work in a loud, wet, and potentially dangerous environment. To negotiate these expectations and constraints, the researcher wore a body camera while working alongside research participants, allowing her to capture a first-person perspective as she assisted animal keepers and volunteers in cleaning enclosures and caring for animals. Although the use of a body camera posed certain complications in terms of both audio quality and camera placement, participating while recording provided a unique window into participants’ daily work experiences, and helped the researcher build strong, mutually beneficial relationships at the field site. For these reasons, this article argues that body cameras create new possibilities for both capturing first-person perspectives in mobile settings, and for allowing researchers to more fully collaborate with their participants.

Keywords: Body cameras, researcher participation, ethnography, research ethics, wildlife conservation

1. Introduction

Through the examination of recordings of naturally occurring interactions, the field of conversation analysis “aims to discover the natural living order of social activities as they are endogenously organized in ordinary life, without the exogenous intervention of researchers” (Mondada, 2012, p. 34). Body cameras offer new possibilities for collecting this type of data, as they “provide a first-person perspective recording of the visual array (wide-angle, High-Definition), sound (especially speech), actions performed with the hands, [and] also a good sense of motion and attention focus” (Lahlou et al., 2015, p. 219). The small size and mobility of body cameras allow researchers to more easily capture participants’ movements and may help the camera become less obtrusive and noticeable to participants.

When research participants wear body cameras, researchers can gain a detailed understanding of what participants are attending to (Brown et al., 2013; Lahlou et al., 2015; Mitsuhara, 2019 pp. 63-66). However, when researchers themselves wear body cameras, not only do we capture our own first-person experiences, but we are also able to participate more fully in the interactions we are studying. This ability to conduct participant observation as we record opens up new possibilities for “subjecting [ourselves]....to the set of contingencies that play upon a set of individuals....so that [we] are close to them while they are responding to what life does to them” (Goffman, 1989, p. 125). However, participating while recording can also complicate our roles at our field sites, particularly if we are concerned about avoiding “exogenous intervention” in these interactions, as Mondada (2012, p. 34) describes.

In this article, I explore the affordances and limitations of using body cameras in my experience researching communication at the Limbe Wildlife Centre, a wildlife sanctuary located in Cameroon. I began fieldwork in Limbe with the goal of understanding how Cameroonian animal keepers and European volunteers worked across linguistic and ideological barriers to rehabilitate chimpanzees. Following Goodwin’s (2018) call to shift “focus from self-sufficient bodies, utterances, and sentences to an interactively sustained field able to encompass multiple actors with diverse abilities” (p. 80), my goal was to use video recordings to capture not only participants’ speech, but also their gestures, facial expressions, and the way they engaged with the world around them. However, in addition to the logistical complexities of keeping a camera trained on people moving across large spaces, and out of the hands of curious chimpanzees, I faced an unanticipated complication—research participants expected me to not only study the work of animal rehabilitation, but also to contribute directly to the physical labor this work requires. In a desire to foster respectful and collaborative relationships with research participants, I therefore revised my research methodology after my first few weeks in the field, making the decision to record while also participating in daily work activities at the sanctuary.

In order to capture interactions between animal keepers and foreign volunteers while also participating alongside them, I wore a body camera. Recording with a body camera allowed me to capture video of participants as they worked together to feed animals, scrub floors, empty wheelbarrows, and coax reluctant chimpanzees, and to keep my hands free to do this work alongside them. Balancing my responsibilities as a volunteer and as a researcher led to numerous challenges—both in terms of what I was able to record, and in navigating conflicts between my role as a researcher and my role as a volunteer. However, participating while recording allowed me to capture a first-person perspective of the complexities of wildlife conservation work, as well as to build strong, mutually beneficial relationships with my research participants.

2. Studying Daily Interactions at a Cameroonian Wildlife Sanctuary

For over twenty-five years, the Limbe Wildlife Centre (LWC) in southwestern Cameroon has been home to several hundred animals, including chimpanzees, gorillas, and other primates, as well as other native mammals, birds, and reptiles. These animals arrived at the LWC after being confiscated from illegal wildlife trafficking, and require intensive physical and social rehabilitation. The fifteen animal keepers at the LWC all come from Cameroon and are responsible each day for the rigorous physical labor involved in cleaning and maintaining enclosures, as well as feeding and monitoring animal behavior. Animal keepers are assisted by a rotating group of volunteers, mainly from Europe, who pay 300 Euros per week to assist animal keepers with their work. The majority of these volunteers have little to no prior experience working with wild animals, and normally stay for around a month on what some describe as a “working vacation.”

Between 2017 and 2018, I conducted nine months of fieldwork at the Limbe Wildlife Centre, during which time I spent about 60 hours each week at the sanctuary, balancing responsibilities as both a researcher and a volunteer. From the outset, I was interested in how this world-renowned sanctuary maintained a reputation for success amidst the great linguistic, cultural, and ideological tensions inherent to transnational environmental conservation work (see Pouchet, 2020; Parreñas, 2018; Tsing, 2005), and amidst escalating conflicts between Cameroon’s Anglophone and Francophone communities (see Maclean, 2019; Biloa & Echu, 2008; Nyamnjoh, 1999). Inspired by earlier analyses of cross-cultural communication (Gumperz, 1992; Jacquemet, 2011; Bailey, 1997) and embodiment and co-operative action (Goodwin, 2000, 2018; Goodwin & Cekaite, 2018; Murphy, 2005), I wanted to explore what “successful” environmental conservation looked like on the ground, in daily workplace interactions.

Many of these interactions occurred during the morning cleaning, when animal keepers and volunteers worked together to remove waste from enclosures, hose down cages, and clean floors. This work bears many similarities to mucking out a sheep stable, as described by Keevallik (2018). Both cases constitute “a multiactivity setting, with dual opportunities for engagement in work and talk, which constitutes a practical challenge for the participants” (p. 313), as both the work itself and the conversation that occurs during it are embodied. In these settings, gaze and body orientation often play a more significant role than they do in ordinary conversation, as participants must often do extra communicative work to gain another’s attention, make themselves heard in a noisy environment, and manage simultaneous conversation and physical work tasks.

Keevallik’s study of mucking out a sheep stable uses data recorded over the course of a single day, using a camera on a tripod. In my fieldwork (see Edmonds, 2019), however, I collected ethnographic data in addition to recordings of workplace interactions, so that my analyses could move between larger-scale analysis of ideologies about language and conservation, and microanalyses of how individuals manage, reinforce, or resist those ideologies as they work together to keep wild animals clean, healthy, and entertained. In total, I collected over 100 hours of video of naturally occurring workplace interactions. While I filmed some of these interactions using a Canon Vixia HF R700, I recorded the majority of my data while wearing a GoPro HERO4 attached to a baseball hat.

The use of the GoPro allowed me to record hands-free so that I could simultaneously participate in routine work activities alongside my research participants and follow them as they moved about the sanctuary. Unlike mucking out a sheep stable, which generally occurs in one relatively small room, daily animal care at the Limbe Wildlife Centre involves animal keepers and volunteers pushing wheelbarrows back and forth across the sanctuary, moving in and out of large outdoor enclosures and smaller overnight dormitories over the course of about three hours each morning. As Brown et al. (2013) describe, in situations like these, where participants “are largely mobile, fixed cameras are of limited use” (p. 1033). In order to capture the work of animal keepers and volunteers, and the ways in which they work together, it would be impossible to use a standard camera mounted on a tripod. Instead, a body camera is ideal for this kind of situation, as it affords the cameraperson a high degree of hands-free mobility, while limiting the amount of cords and other equipment that needs to be carried around and kept out of reach of curious chimpanzees.

3. Satisfying Community Expectations through Participant Observation

Although prior to my arrival in the field, I did not anticipate the degree to which I would be expected to participate in daily work activities at the sanctuary, I had always intended to use participant observation as a core methodology for this project. Participant observation allows researchers to examine “firsthand and up close how people grapple with uncertainty and ambiguity, how meanings emerge through talk and collective action, how understandings and interpretations change over time, and how these changes shape subsequent actions” (Emerson et al., 2011, p. 5). Working as a volunteer allowed me to contextualize my research participants’ linguistic practices and gain a more comprehensive view of the work involved in operating the sanctuary. The sanctuary’s volunteer program was in many ways ideally suited for this approach: At the LWC, it is commonplace for new people to come to the sanctuary with the goal of learning about and participating in its daily work practices. While most of these people are inexperienced European volunteers on vacation, the LWC does host some students and researchers (mainly biologists and primatologists).

My original research plan involved spending my first month in Limbe working as a volunteer, taking field notes but waiting to record or conduct interviews. I believed that this approach would allow me to begin developing relationships with staff and volunteers, to learn firsthand about how the sanctuary works, and to demonstrate my commitment to assisting with the work of wildlife conservation. After the first month, I intended to spend the majority of my time recording staff and volunteers as they fed animals, cleaned cages, repaired equipment, and educated tourists, rather than participating in these activities myself.

However, by the end of this first month, I had learned that whether or not the primary focus of my research involved working with animals, there was little room for observers in the daily operations of the sanctuary—the physical labor involved in animal care required as many hands as possible. As the sanctuary had a shortage of permanent animal keepers, it relied on the assistance of volunteers. However, the number of volunteers at the sanctuary varied during my fieldwork from as many as fourteen to as few as three, with an average of six volunteers at any given time. When there was a shortage of volunteers, animal keepers faced a dramatic increase in their already demanding workload, and I quickly felt uncomfortable standing to the side with my video camera while they struggled.

As I learned about the intensity of the physical labor required to keep the sanctuary running, I was also learning about social divisions within the sanctuary—in particular, that there was a stark contrast between the people whose work day oriented around “the cleaning,” and those whose work focused on managerial or research-based tasks. “The cleaning,” as staff call it, refers to the intensive physical labor that occurs at the sanctuary each morning. This work is led by animal keepers, mainly Cameroonian men in their fifties, most of whom have worked at the sanctuary for ten or even twenty years. Assisting them are largely inexperienced foreign volunteers, who normally only stay at the sanctuary for a few weeks.

After feeding animals and releasing them into their outdoor enclosures, keepers and volunteers spray down cages with a hose, then rake and sweep animal feces, fruit peels, and other waste into a wheelbarrow, which they push across the sanctuary to refuse piles. They then scrub shelves, platforms, and other equipment, rinse cages, and use squeegees to dry floors. This work is extremely physically demanding, and also generally occurs in 80-90˚ Fahrenheit heat (26-32˚ Celsius) with 90% or higher humidity, and under heavy rain for about half the year. “The cleaning” must also be accomplished as quickly as possible—the longer it takes, the hotter it becomes, and the more likely it is that Limbe’s limited running water supply will decrease or stop entirely.

While the majority of the sanctuary’s daily operations orient around accomplishing “the cleaning” as quickly and thoroughly as possible, there is a small group of people who are exempt from this physical labor. This group includes the sanctuary’s managers (a married couple from France), and the students who apprentice underneath them. These students were all white and French during my time in the field, and while they were required to help with “the cleaning” when they first arrived at the sanctuary, after a few weeks they spent most of their time conducting observations of animals, analyzing data, fundraising, or assisting with other managerial tasks. These activities left them exempt from “the cleaning” during the majority of the week.

This division of labor led to a racialized hierarchy between overburdened Cameroonian animal keepers and mainly white foreign managers and students who, keepers often complained, seemed to consider themselves too important to contribute to the physical labor required to keep the sanctuary’s animals healthy and fed. Although this group of foreigners did not assist with cleaning, they were generally the ones who made the majority of decisions about how the sanctuary should operate. This led to frequent complaints from keepers that management’s decisions were often out of sync with the logistical realities of animal keeper work.

As a white foreigner myself, I felt that withholding my physical labor in favor of research activities would constitute participation in the racialized hierarchy at the sanctuary that I hoped to critique. And as my research relied upon animal keepers’ willingness to work with me—both to let me record their daily activities, and to answer my questions—earning and maintaining their respect was absolutely critical. For these reasons, I made the decision to adapt my research plans to allow me to continue to contribute more directly to work activities at the sanctuary. Assisting with the cleaning throughout my time in Limbe—contributing my own physical labor, following keepers’ directions, and helping to ease their workload—played an important role in developing positive relationships with my research participants, based on mutual respect and a desire to help each other. These positive relationships in turn gave me access to situations I would otherwise have been unable to record, and the context I needed to understand them.

4. The Advantages of Combining Video Recording and Participant Observation

In order to fulfill research participants’ expectations that I contribute to the sanctuary’s daily work, on a normal day of fieldwork, I joined staff and volunteers at 8:00 in the morning for a staff meeting, after which I changed into the same protective gear as my participants: heavy knee-high rubber work boots, elbow-length red rubber gloves, and a face mask. I then joined animal keepers to feed chimpanzees and begin cleaning. Around this time, I would often put on a backwards baseball hat with a GoPro attached. For the next two to three hours, I recorded while assisting animal keepers and other volunteers. Once the morning’s work was done, we would break for lunch, and I would then spend afternoons conducting interviews with staff and volunteers, or recording staff meetings, education programming, or guided tours at the sanctuary – this time in a more traditional set-up with a Canon Vixia HF R700. At 4:00 in the afternoon, I rejoined keepers to bring animals inside for the night, and work would finish for all of us around 5:00 pm.

Using a body camera during morning work had several advantages, which I discuss in detail below. It allowed me to stay mobile, following people in and out of tight spaces, while capturing a detailed, first-person perspective of how animal keepers and volunteers work together. Most importantly, however, the use of a body camera allowed me to gather recorded data while also working alongside my research participants, enabling my analyses to include both small interactional details, as well as larger ethnographic and contextual information that would not have been available to me otherwise.

4.1 Capturing an embodied first-person perspective

In addition to enabling me to follow research participants as they moved in and out of enclosures, using a body camera while conducting participant observation allowed me to capture a first-person perspective of how animal keepers and volunteers work together and manage misunderstandings. This work is highly embodied, involving tool usage and copious deictic gestures among other paralinguistic resources, as animal keepers give directives to volunteers. These directives frequently occurred and were carried out entirely nonverbally, as Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate.

Figures 1a and 1b.

An animal keeper silently points to a pile of greens (1a), then points to a cage (1b), giving a nonverbal directive to the researcher to feed chimpanzees.

Figures 2a and 2b.

A first-person view of the researcher (wearing red rubber gloves) carrying out the nonverbal directive shown in Figure 1. In Figure 2a, the researcher retrieves greens from the pile indicated by the animal keeper in Figure 1a. In Figure 2b, the researcher scatters those greens around the cage indicated by the keeper in Figure 1b.

In Figures 1 and 2, Wilson, an experienced animal keeper, looks at me and wordlessly points to a pile of greens (Figure 1a), and then to a chimpanzee cage (Figure 1b). Because of our prior experience working together, I am able to carry out his directive, retrieving greens (Figure 2a) and placing them in the appropriate cage (Figure 2b). This interaction—which is typical in this setting—occurs entirely nonverbally, in the confined quarters of a hallway between cages. Combining participant observation with the use of a body camera enables me to capture the subtleties of this non-verbal communication that occurs as volunteers and animal keepers work together. At the same time as I am capturing this data, I am also experiencing what it is like to orient my body and attention so that I can make sense of and carry out these nonverbal directives, helping me to understand the potential difficulties my research participants face in this process. Finally, the fact that I am doing the work of bringing greens into an enclosure means that Wilson does not have to and can focus on more important tasks.

4.2 Incorporating ethnographic perspectives into the analysis of video-recorded interactions

Recording a first-person perspective as I worked alongside animal keepers and volunteers also gave me insight into how hierarchies of knowledge and power at the sanctuary unfold over time and space. In the following extract, I am working alongside animal keepers Wilson and Thomas, as well as a volunteer named Sara. Sara is a French biology student monitoring the introduction of three young chimpanzees into a large group of mature chimpanzees. As part of this introduction process, animal keepers must conduct the complex and potentially dangerous work I have elsewhere described as “chimp tetris” (see Edmonds, 2019), as they release some chimpanzees into an outdoor enclosure, while coaxing others into particular cages. On this day, approximately five months into my time in the field, the goal of “chimp tetris” is to send all chimpanzees outside with the exception of Suzanne and Ewake, who have been chosen to meet the new chimpanzees.

As Thomas and Wilson attempt to enact this plan, they face an additional complication: chimpanzee Yabien has decided to stay inside with Suzanne and Ewake. Thomas, Wilson, and Sara can all see that Yabien has created a problem by refusing to go outside. However, the animal keepers see this as a problem related to their own domain—the mechanics of moving chimpanzees. They have been discussing in Cameroonian Pidgin English how to manage this situation and decide to leave Yabien inside temporarily in order to finish cleaning. Sara, who is a novice speaker of English, and does not understand Pidgin, sees Yabien as a problem related to her domain—making sure the introduction follows the plan.

Extract 1

Figure 3

Line 8: Volunteer Sara points out chimpanzees to animal keepers.

Figures 4a and 4b.

Line 17: Wilson makes a “stop” gesture at Sara.

Line 27: Wilson smiles at the researcher.

In line 1, despite the fact that Sara is decades younger and less experienced than Thomas and Wilson, she issues a declarative with a tag, asserting that Yabien will not go in with “the girls” (i.e., the new young chimpanzees). There is a pause in line 2, as keepers interpret Sara’s utterance. Thomas then explains that Yabien will not be introduced to the new chimpanzees, but does not want to leave Suzanne (lines 03-04). Sara switches briefly to French (lines 05, 08), perhaps hoping that Thomas (a fluent French speaker) will also switch to explain what is happening. He continues in English, however, interpreting Sara’s utterances as confusion over the location of different chimpanzees, rather than which chimpanzees will be involved in the introduction (line 09). Sara reformulates her problem in lines 11 and 15, again asserting that Yabien should not be inside.

Thomas begins another explanation in line 18, but Wilson interrupts him, declaring with “no questions now” that Sara does not have the right to know the plan at this time. Between lines 20 and 30, Wilson explains this slowly, pausing frequently, but using falling intonation to demonstrate that the matter is not open for discussion. Wilson closes by acknowledging his awareness of the plan and his intention to follow it (line 30). Sara, seeming to recognize his annoyance, repeats “yes” and “okay” (lines 22, 24, 26, 31), demonstrating her willingness to agree.

By using a body camera to record this extract, I am able to capture the activities of research participants as they move through tight spaces. More importantly, the use of the body camera enables me to work alongside my research participants, so that I am able to contextualize their interactions. In this extract, I understand Sara’s concern with balancing her responsibilities to both keepers and management because I have worked alongside her, go to the same meetings, and hear her complain over dinner after work. I can also understand the keepers’ concerns, as I have been working alongside them for months as they compliment and complain about different situations and types of volunteers, in both interviews and casual conversations.

My participation in work at the sanctuary eventually led to people treating me more as a member of the field site, rather than as a researcher (see Hofstetter, 2021/this issue and Pehkonen et al., 2021/this issue, for additional discussions of researchers as members). This is visible in line 27 of the transcript (Figure 4b), as Wilson smiles at me after chastising Sara. I interpret this as a “conspiratorial glance,” an acknowledgment from Wilson that I understand the animal keepers’ plans to move chimpanzees, even if Sara does not. It may also serve as a request for me to explain the situation to Sara,1 if she does not accept the keepers’ explanations. As this extract demonstrates, the use of a body camera during my participation allows me to both gather and contextualize recorded data in a way that would be impossible if I were standing behind a camera on a tripod. Furthermore, participating alongside my research participants helps me build relationships and demonstrate my commitment to our shared goal of caring for rescued wildlife.

5. The Logistical and Ethical Challenges of Managing Research and Community Expectations

While using a body camera allowed me to record hands-free and meet participants’ expectations that I contribute to the work of the sanctuary, there were numerous challenges to recording in this environment. During the rainy season in Limbe, it may rain for hours or days at a time. Besides the weather, the work of caring for animals is also not amenable to keeping recording equipment clean, safe, or dry. Animal care involves spraying down cages with hoses, hauling buckets of water, and mopping, in addition to chopping and throwing sticky fruits. Indeed, the concern of damaging equipment was one of the major reasons participants cited for not wanting to wear the camera themselves. The GoPro’s durability and water-resistance make it well-suited to these conditions, and I also mitigated the risk of damage to equipment through the careful use of a combination of plastic bags, waterproof storage cases, and silica packets.

In addition to preventing damage to equipment, the sound of rain, running water from a hose, and chimpanzee shouts interfered with my ability to record high quality audio. While external microphones helped, participant observation allowed me to understand how these recording challenges were also complications my participants faced understanding each other. Work conversations occurred over running water and animal cries, across large distances, and in non-native or non-preferred languages (see Edmonds 2020 for a discussion of language choice at the sanctuary). For these reasons, gestures and facial expressions held additional importance in their work.

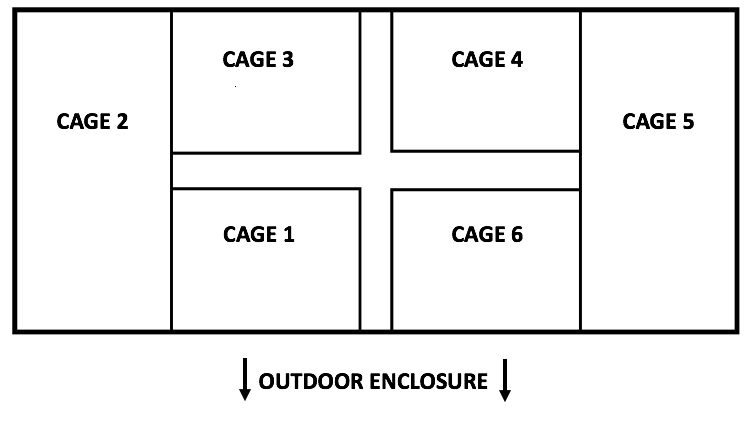

Alongside water and noise-related complications, the animals themselves posed challenges to recording. The majority of cleaning work takes place in the primates’ overnight enclosures—for chimpanzees, this consists of a group of six medium-sized rooms, connected by a narrow cross-shaped aisle (see Figure 5). Keepers send most chimpanzees into a large outdoor enclosure before they begin cleaning, and although people are never inside cages with chimpanzees,2 there are often chimpanzees in neighboring cages — those that are undergoing more intensive monitoring, or who have come back inside for a rest. Chimpanzees tend to be very curious about human activities and equipment, and a broom, hose, or camera left too close to one of the cages can quickly become a new toy for a sneaky chimpanzee. Chimpanzees often expressed interest in my recording equipment, and I had to remain constantly vigilant to avoid losing a camera to grabbing chimpanzee hands.

Figure 5. Map of indoor chimpanzee enclosure.

In addition to these physical complications, managing simultaneous participation and recording sometimes led to difficulties regarding who and what I was able to record. One of the primary goals of the project was to capture naturalistic interactions between animal keepers and foreign volunteers. As I was now treated as a volunteer as well as a researcher, when the sanctuary was short-handed I was sometimes the only volunteer assigned to my section, along with one or two keepers. On these days, each of us would work alone cleaning separate cages, leaving few interactions for me to record.

Keepers’ eventual trust in my abilities as a volunteer also led to situations where they assigned me a task to complete independently while they had an interaction in another room that I would very much like to have recorded. For example, in an incident I have discussed elsewhere (Edmonds, 2019), while keepers attempted to implement the introduction process I describe in Extract 1, a large fight occurred between two groups of chimpanzees, and keepers had to call managers in for help deciding how to continue. As the fight had also delayed the cleaning, the keeper I was working under asked me to continue working on my own while keepers stepped outside to discuss solutions with the managers (see Figure 6).

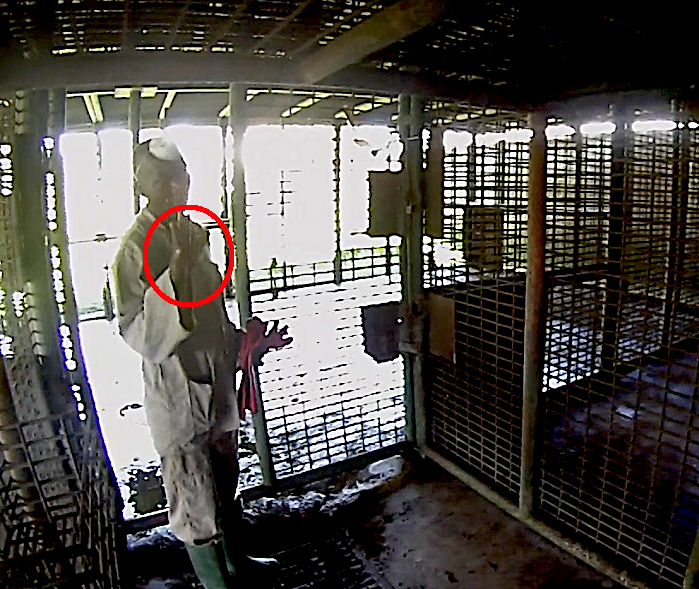

Figure 6.

The researcher gazes down the hall at an impromptu meeting between managers and animal keepers (center), unable to record the meeting because animal keepers have requested that she continue cleaning.

These situations illustrate the tensions I wrestled with throughout my time in Limbe, as I balanced my research goals with the expectations of the community who had graciously allowed me to work with them. I took pride in the skills I had gained as a volunteer, and in earning the trust of animal keepers. However, I also could not help but feel disappointed when my participation at the sanctuary left me unable to record a piece of interesting data. I also worried regularly, especially when training new volunteers, about my own influence on the “naturalistic” interactions I was recording. If I were not present, it is true that someone else would be explaining to new volunteers the best way to hold a shovel, or why we were taking time to spread bananas throughout an enclosure rather than leaving them in one large pile. However, would someone else be explaining these things in the same way? How much were my explanations informed by my experience working at the sanctuary as a volunteer, and how much were they informed by the critical perspective I applied as a linguistic anthropologist interested in analyzing these types of interactions? By the end of my time in Limbe, staff treated me as having the same skills and knowledge as any other experienced volunteer. In many respects, my motivations were also the same as other experienced volunteers: to contribute to the work of wildlife conservation. However, my background and goals as a linguistic anthropologist made it impossible for me to be entirely (or exclusively) a member of the community I was studying.

6. Conclusion

When research participants give us permission to record their daily activities, they are offering to share with us their time and expertise, in addition to opening themselves up to our scrutiny. To do justice to this generosity, researchers must behave ethically and meet the expectations of the communities we study (see also Chen, 2021/this issue and Goico, 2021/this issue, for detailed discussions of ethics and researcher participation). This is of even greater importance when we are studying power and inequality, and when we are not ourselves members of historically marginalized populations. In the case of my research at the Limbe Wildlife Centre, meeting community expectations meant contributing my own physical labor to the work of animal care, in addition to working toward my own goals of recording and analyzing this work.

Recording at the wildlife sanctuary posed a considerable number of challenges—not only in terms of the highly-mobile nature of animal care, but also Limbe’s intense heat and humidity, and the generally noisy conditions of the sanctuary. In this setting, it would have been impossible to capture much with a camera on a tripod—there was no safe, dry place to put one, and participants would constantly have been moving off screen and out of earshot. Using a body camera enabled me to safely follow my participants as they moved from space to space, and to keep my hands free to work alongside them. Experiencing these difficult communicative conditions as both a researcher and a volunteer improved my ability to understand the obstacles that my participants faced as they worked together.

Many of the logistical challenges I faced at my field site—wet, noisy conditions, proximity to curious and potentially dangerous animals—are not unique to Limbe, but rather normal in many contexts where humans and non-human animals interact. As scholarly interest in the complexity of human-animal interactions grows (see Brown & Banks, 2015; Mondémé, 2011; Takada, 2013), researchers must find creative solutions for video recording safely and effectively. In my experience, the small size and durability of body cameras make them ideal for overcoming many of these obstacles. Furthermore, the affordances of body cameras for capturing a first-person, wide-angle perspective is especially useful in close quarters such as cages and enclosures.

In addition to its usefulness in overcoming logistical challenges, the use of a body camera allowed me to record and conduct participant observation simultaneously. My role as both a researcher and a volunteer at the LWC helped me build strong relationships with research participants, gave me access to a wider variety of interactions, and also helped me contextualize these recordings. Using more traditional recording methods in these contexts can of course lead to rich data and analyses, such as Keevallik’s (2018) argument about the ways in which embodied actions shape the treatment of different utterances issued during physical labor. However, participant observation specifically, and ethnography more generally, enable us as researchers to both document and analyze the ways in which power unfolds not only in one particular interaction, but across different types of interactions, shaping relationships between participants.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the staff and volunteers of the Limbe Wildlife Centre for their participation and generosity throughout the research process. The author is also particularly grateful to Marjorie Harness Goodwin, Julia Katila, Yumei Gan, Sara Goico, and two anonymous reviewers for their feedback on various drafts of this manuscript. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (Gr. #1657789), the Wenner-Gren Foundation (Gr. #9455), and the UCLA International Institute.

References

Atkinson, J.M. & Drew, P. (1979). Order in court: The organisation of verbal interaction in judicial settings. London: MacMillan.

Bailey, B. (1997). Communication of Respect in Interethnic Service Encounters. Language in Society 26(3), 327-356.

Biloa, E. & Echu, G. (2008). Cameroon: Official Bilingualism in a Multilingual State. In Simpson, A. (Ed.), Language and National Identity in Africa (pp. 199-213). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brown, B., McGregor, M., & Laurier, E. (2013). iPhone in vivo: Video Analysis of Mobile Device Use. CHI 2013, April 27-May 2, 2013. Paris, France. pp.1031-1040.

Brown, Katrina M., & Banks, Esther (2015). Close encounters: Using mobile video ethnography to understand human-animal relations. In. C. Bates (Ed.), Video methods: Social science research in motion (pp. 95−120). Abingdon, OX: Routledge.

Chen, R. (2021). The interplay of participant roles in collecting video data of non-speaking autistic individuals. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 4(2).

Edmonds, R. (2019). Language Ideologies, Conservation Ideologies: Communication and Collaboration at a Cameroonian Wildlife Sanctuary. PhD dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles.

Edmonds, R. (2020). Multilingualism and the politics of participation at a Cameroonian wildlife sanctuary. Language and Communication 72, 1-12.

Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., and Shaw, L.L. (2011). Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Second Edition. Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Goffman, E. (1989). On fieldwork. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 18(2), 123-132.

Goico, S. (2021). The Participation Role of the Researcher as a Co-operative Achievement. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 4(2).

Goodwin, C. (2000). Action and Embodiment Within Situated Human Interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 32, 1489-522.

Goodwin, C. (2018). Co-Operative Action. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Goodwin, M. H. & Cekaite, A. (2018). Embodied Family Choreography: Practices of Control, Care, and Mundane Creativity. London: Routledge.

Gumperz, J. J. (1992). Contextualization and Understanding. In Duranti, A. & Goodwin, C. (Eds.), Rethinking Context: Language as an Interactive Phenomenon. (pp. 229–252). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hofstetter, E. (2021). Analyzing the researcher-participant in EMCA. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 4(2).

Jacquemet, M. (2011). Crosstalk 2.0: Asylum and Communicative Breakdowns. Text & Talk 31(4), 475–497.

Keevallik, L. (2018). "Sequence Initiation or Self-Talk? Commenting on the Surroundings While Mucking out a Sheep Stable", Research on Language & Social Interaction 51(3), 313-328.

Lahlou, S., Le Bellu, S., & Boesen-Mariani, S. (2015). Subjective Evidence Based Ethnography: Method and Applications. Integr Psych Behav 49, 216-238.

Maclean, R. (2019). Cameroon Anglophone Separatist Leader Handed Life Sentence”. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/aug/20/cameroon-anglophone-separatist-leader-ayuk-tabe-handed-life-sentence?CMP.share_btn_link

Mehan, H. (1979). Learning Lessons: Social Organization in the Classroom. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mitsuhara, T. V. (2019). Moving Toward Utopia: Language, Empathy, and Chastity among Mobile Mothers and Children in Mayapur, West Bengal (Doctoral dissertation). Available from Proquest Dissertation & Theses Global Database.

Mondada, L. (2012). The Conversation Analytic Approach to Data Collection. In Sidnell, J. & Stivers, T. (Eds.) The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. pp.32-56. Chichester: Blackwell-Wiley. DOI: 10.1002/9781118325001.

Mondada, L. (2013). Interactional Space and the Study of Embodied Talk-Interaction.In Auer, P., Hilpert, M., Stukenbrock, A., & Szmrecsanyi, B. (Eds.) Space in Language and Linguistics: Geographical, Interactional and Cognitive Perspectives. pp. 247–275. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Mondada, L. (2014). Bodies in action: Multimodal analysis of walking and talking. Language and Dialogue. 4(3), 357-403.

Mondémé, C. (2011) Animal as subject matter for social sciences: when linguistics addresses the issue of dog's "speakership". In Non-humans in Social Science: Animals, Spaces, Things, pp.87-104. Pavel Mervart,

Murphy, K. (2005). Collaborative imagining: The interactive use of gestures, talk, and graphic representation in architectural practice. Semiotica 156, 113-145.

Nyamnjoh, F. (1999). Cameroon: A Country United by Ethnic Ambition and Difference. African Affairs. 98, 101–118.

Parreñas, R. S. (2018). Decolonizing Extinction: The Work of Care in Orangutan Rehabilitation. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Pehkonen, S., Rauniomaa, M., and Siitonen, P. (2021). Participating researcher or researching participant? On possible positions of the researcher in the collection (and analysis) of mobile video data. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 4(2).

Pouchet, J. (2020). The Circulation, Durability, and Erasure of Brands in a Biodiversity Hotspot. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 30(1), Early view.

Tsing, A. (2005). Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

West, C. (1984). Routine complications: Troubles with talk between doctors and patients. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

1 As a fluent speaker of both English and French, as well as an experienced volunteer, I was often asked to translate or elaborate when French volunteers had difficulty understanding animal keepers’ instructions.↩

2 Direct human-chimpanzee contact poses significant risks to both parties. Diseases like tuberculosis or hepatitis may be transmitted between humans and chimpanzees, and chimpanzees can also be very aggressive, posing a physical threat to humans. Finally, direct contact with humans is detrimental to the social rehabilitation of chimpanzees, many of whom were rescued from the pet trade and must relearn appropriate chimpanzee social behaviour.↩