Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

The Gratitude Opportunity Space: The timing of gratitude expressions in object passes

Darcey K. deSouza1, Song Hee Park2, Wan Wei2, Kaicheng Zhan2, Galina B. Bolden2, Alexa Hepburn2, Jenny Mandelbaum2, Lisa Mikesell2, Jonathan Potter2

1Northeastern University

2Rutgers University

Abstract

This paper examines the situated use of expressions of gratitude and demonstrates how their precise timing matters for coordinating actions and managing relationships in social interaction. Focusing on activities that involve object passing, we introduce the concept of the gratitude opportunity space, a standard time for expressing gratitude. We explicate three discernable phases within the gratitude opportunity space for simple recruitment sequences involving an object pass (pre-delivery, on-delivery, and post-delivery positions) and explore how the gratitude opportunity space is dynamically recalibrated according to the activity underway in other activities that involve object passes (i.e., remote offers of objects and gift giving). Data are American and British English.

Keywords: Gratitude, Recruitment, Politeness, Conversation Analysis

1. Introduction

“You cannot do a kindness too soon because you never know how soon it will be too late.” —Ralph Waldo Emerson

This paper examines the situated use of expressions of gratitude in everyday life. Our goal is to demonstrate that – and how – the precise timing of gratitude matters for coordinating actions and managing relationships in social interaction. In contrast to much research that has conceptualized gratitude as a psychological state or as an act of politeness, we take an interactional approach to gratitude to explore how, when, and for what interactional purposes people deploy expressions of gratitude in a range of social activities. Extending prior interactional research examining the deployment of expressions of gratitude in everyday talk, we aim to answer a simple question: when should gratitude be expressed? More technically, we are concerned with how the precise timing of gratitude expressions is sensitive to the unfolding activity of which it is part. We introduce the concept of the gratitude opportunity space – a standard time period for expressing gratitude - and show how it is organized for different activities involving the passing of objects.

To explicate the organization of the gratitude opportunity space, we primarily focus on expressions of gratitude (such as “thank you” or “thanks”) in recruitment sequences, i.e., episodes in which participants assist one another in the accomplishment of practical tasks (Kendrick & Drew 2016; Drew & Kendrick, 2018). Recruitment sequences that involve a transfer of objects from one participant to another (e.g., passing food at mealtimes) create systematic and visible opportunities for expressing gratitude, making it a propitious site for examining the timing of gratitude. We show how expressions of gratitude in this activity may be deployed to do both the relational work of acknowledging the assistance and the transactional work of coordinating the manual object transfer.

2. Literature Review

Gratitude has been examined from psychological, sociocultural, and interactional perspectives.

In psychology, gratitude has been broadly conceptualized in two ways: as a personality trait and as an emotion. As a trait, gratitude refers to a personal ability to notice and appreciate positive aspects of life, such as appreciating the present moment (Wood et al., 2009; Wood et al., 2010;). Both experimental and survey research suggest that trait gratitude promotes well-being, positing a causal effect of gratitude on social relationships, social functioning, stress, and quality of sleep (Emmons & McCullough 2003; Wood et al., 2009; Wood et al., 2010). As an emotion, gratitude has been described as the pleasant feelings one experiences after recognizing something of value has been received from another person (McCullough et al., 2001; McCullough & Tsang, 2004). It is argued that this ‘grateful emotion’ promotes prosocial behaviors (Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006) and can help people recognize the value of their relationships (Algoe et al., 2010; Gordon et al., 2012).

Additionally, psychologists have examined relational benefits of ‘expressed’ gratitude (e.g., saying ‘thank you’ or writing thank-you notes). Studies suggest that expressing gratitude promotes greater feelings of communal strength in the expresser (Lambert et al., 2010), increases relationship satisfaction (Algoe et al., 2013), and reinforces benevolent behaviors of recipients of gratitude expressions (McCullough et al., 2001). Expressed gratitude is also claimed to impact less intimate relationships. For example, writing thank-you notes has been argued to promote affiliation between unacquainted peers (Williams & Bartlett, 2015).

From a sociocultural perspective, gratitude has been conceptualized as the enactment of politeness. This approach originates in Goffman’s (1967) notion of “face,” the social image one projects and protects in social settings. Expressions of gratitude are commonly understood as showing politeness. Drawing on Brown and Levinson’s (1987) politeness theory, research in this tradition examines how expressions of gratitude are influenced by factors such as the degree of imposition the thanked-for service involves and the relationships between the participants (e.g., Coulmas, 1981; Eisenstein & Bodman, 1986; Okamoto & Robinson, 1997; Martínez Robledillo, 2015).

The concept of gratitude as a politeness routine has also underpinned language acquisition and socialization research. These studies examine how adults socialize children to express gratitude, both in the U.S. and cross-culturally (e.g., Blum-Kulka, 1990; Gleason & Weintraub, 1976; Greif & Gleason, 1980; Clankie, 1993; Eisenstein & Bodman, 1993; Garcia, 2016).

In contrast to psychological and sociocultural approaches, interactional research examines how gratitude expressions are deployed in naturalistic, recorded interaction. Studies in this tradition (reviewed below) have considered various contexts in which gratitude is expressed, such as the provision of help, when some form of assistance (either immediate or remote) is provided or offered. Sacks (1992) observed that not all services are thankable. That is, expressions of gratitude are only relevant when one goes above and beyond one’s “category-bound” obligations.

Extending Sacks’ (1992) original observations, Clayman and Heritage (2014) show how expressions of gratitude are used to reflexively construct a benefactive relationship between the speaker and the addressee. Their analysis demonstrates that interactants use various forms of appreciation in response to offers or the granting of requests, including explicit appreciations (e.g., “thank you”), appreciative assessments (e.g., “that’s very sweet of you”), and reciprocations (e.g., a reciprocal offer). According to Clayman and Heritage (2014), these practices not only register the service rendered but also “validate and sustain the benefactive relationship previously in play” (p. 58). Gratitude expressions, in this sense, display the benefactor-beneficiary relationship that results from the service performed or projected.

Other interactional research has considered relative frequencies of expressions of gratitude across languages. Drawing on cross-linguistic corpora of field recordings of conversational materials, researchers have found that expressions of gratitude are rarely used to acknowledge fulfillment of requests in recruitment sequences (Floyd et al., 2018), and when they do occur, they are produced to show appreciation for assistance that is “more-than-expectable on local grounds” (Zinken et al., in press).

Finally, conversation analytic research has examined how expressions of gratitude can accomplish other actions beyond enacting appreciation. For example, expressions of gratitude have been investigated for their role as a conversation closing device in calls to emergency call centers (Raymond & Zimmerman, 2016; Zimmerman & Wakin, 1995) and medical helplines (Woods et al., 2015). In calls to emergency centers, callers recurrently produce “thank you” in response to dispatchers’ service announcements (e.g., “We’ll send someone”), which accepts the provision of service and thereby advances the call toward closing (Raymond & Zimmerman, 2016; Zimmerman & Wakin, 1995). Similarly, in medical helplines, patients use “thank you” to appreciate nurses’ advice-giving and to move to call closure (Woods et al., 2015). These studies thus show how expressions of gratitude can be deployed to accomplish both the relational work of appreciation and the coordinating work of activity closure.

In this paper, we extend the interactional approach to the study of gratitude by investigating precisely when, in the course of an ongoing activity, gratitude is expressed. We analyze different activities involving object passes, including recruitment sequences, remote assistance, and gift-giving. We have chosen to focus on this because object passes involve precise coordination between participants (as shown by Due & Trærup, 2018; Heath et al., 2018; Tuncer & Haddington, 2020). Additionally, this provides us with a physical, visible environment in which to explore the timing of expressions of gratitude. We first explicate three discernable phases within the gratitude opportunity space for recruitment sequences, what we refer to as object pass simpliciter (cf. Schegloff, 2007): pre-delivery (“thank you” is produced as the object is lifted), on-delivery (“thank you” is timed to coincide with the hand-over of the object), and post-delivery (“thank you” begins just after the recipient takes the object). We then examine expressions of gratitude in other activities involving an object transfer (remote offers and gift giving) to show variations in the timing of the gratitude opportunity space. Our analysis shows that expressions of gratitude may implement somewhat different actions depending on when, precisely, they are produced in the course of object delivery.

3. Data and Method

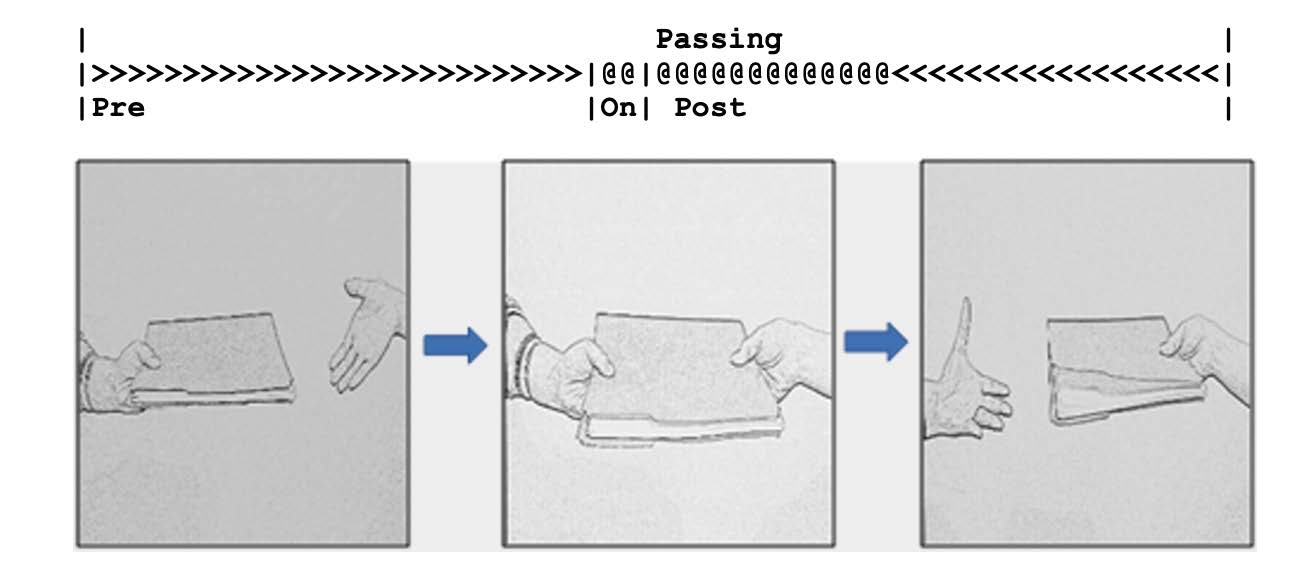

The data consist of video recordings of naturally occurring everyday interactions between friends and family. Data are in American and British English (with some instances from bilingual data). In accordance with conversation analytic methodology (Sidnell & Stivers, 2013), we identified, transcribed (Hepburn & Bolden, 2017; Mondada, 2018), and analyzed over 120 segments containing expressions of gratitude (such as different forms of “thank you”) and appreciation (e.g., “wow”). The analysis presented in this paper is chiefly based on a sub-collection of 57 cases in which gratitude is expressed in the context of object transfers.i To capture details of an embodied object transfer trajectory, the following symbols are used (see also Figure 1):

>>> indicates movement to deliver the object by the passer;

@@@ indicates that both participants are holding the object; <<< captures the withdrawal of the object by the recipient.All names and other identifiers have been changed in the transcripts.

4. Analysis

In examining the positioning of expressions of gratitude in the manual passing of objects, we rely on prior work on the phasal organization of gestures and other body movements (Kendon, 1972; 1980; Kita et al., 1997). In a recent study, Lerner and Raymond (2017) developed the concept of the “Manual Action Pathway” for analyzing a range of manual actions. The manual action pathway consists of three phases: the preparation phase when the body begins to move out of “home position” (Sacks & Schegloff, 2002) to prepare for the upcoming action, the focal action phase during which the bodily action is accomplished, and the return phase, when the body returns to home position.

Based on the understanding that physical actions have phasal structures, we find that for the object pass simpliciter, that is, simple, here-and-now assistance, expressions of gratitude are precisely timed relative to an object transfer so as to occur during the focal action phase of the manual action pathway. This period of time for producing an expression of gratitude constitutes what we call the gratitude opportunity space. The gratitude opportunity space begins as an object is picked up by the passer and ends when the object is in the other person’s possession. See Figure 1 for a visual representation of the gratitude opportunity space for object passes (and the corresponding transcription symbols).

Within the gratitude opportunity space for an object pass simpliciter, there are three discernable phases where expressions of gratitude are found. First, expressions of gratitude can be timed to occur as an object is being lifted – the pre-delivery phase. Second, expressions of gratitude may be timed to begin precisely when the recipient takes hold of the object – the on-delivery phase. Third, expressions of gratitude may begin after the recipient takes hold of the object – the post-delivery phase. In what follows, we examine each position within the gratitude opportunity space to show how the action implemented through an expression of gratitude is differently inflected by its position relative to the gratitude opportunity space.

We first examine expressions of gratitude that are precisely timed to coincide with object delivery. The onset (or the beginning) of the production of “thank you” or “thanks” occurs just as the object is being placed in the recipient’s hand(s), i.e., during the ‘on-delivery’ phase of the gratitude opportunity space. Our analysis suggests that ‘on-delivery’ expressions of gratitude, on the one hand, acknowledge the passer’s help and, on the other hand, mark the physical handover of the item. In other words, they have a relational function – by responding to the other’s assistance – and a transactional function – by marking the receipt of the object.

This usage of expressions of gratitude is exemplified in the following three cases. In Extract 1, Mom, Dad, Sam, and Ally are about to eat dinner. In the beginning of the extract, Sam holds a container with parmesan cheese out to Ally, who is sitting next to him. Ally reaches her hand out to take the cheese (line 1), and at the moment she takes hold of the container, she starts to quietly produce the expression of gratitude “ºThank you.º” (line 2).

Open in a separate windowIn this case, Ally’s “oThank you.o” is produced as her hand grasps the container of cheese: i.e., the expression is timed to begin at the precise moment at which Ally receives the object. The propositional content of “Thank you” is understandable as expressing gratitude for the object pass. Its timing marks the hand-over of the object from Sam to Ally.

Extract 2 is from a family dinner that includes Ben, his Grandma, and other people who are not involved in this particular segment. Ben asks his Grandma for some salad (line 2). After putting salad on Ben’s plate (line 5), Grandma holds the plate towards Ben while announcing its readiness with “ooHereoo” (line 6). In response to this announcement, and precisely as he takes hold of the plate, Ben produces the expression of gratitude “oThanks gram.o” (line 7). Both Grandma’s announcement and Ben’s gratitude expression are produced quietly (marked on the transcript with degree signs) perhaps so as not to impinge on concurrent conversation.

Open in a separate windowNote that Ben extends the expression of gratitude with the address term “gram” so that the ending of Ben’s turn coincides with Grandma releasing the plate. In this way, the particular design of the expression of gratitude may help to coordinate the passer and receiver’s movements in the course of object delivery: it begins when Ben takes hold of the plate and ends when Grandma releases the plate.

We also find expressions of gratitude that occur after an item has been offered and as it is subsequently delivered. In Extract 3, six participants are at a family dinner table. Mom offers the asparagus to Lydia (lines 1-2). Lydia accepts the offer with “Yes::” (line 3). Note that Mom is already holding the dish out towards Lydia when the offer is produced and accepted. Then, at the exact moment at which Lydia takes hold of the plate, she produces “oThank you.o” (line 5).

Open in a separate windowHere, “Thank you” begins when Lydia takes hold of the plate and ends after Mom releases the plate. In other words, the expression of gratitude is coordinated with the embodied action of handing over the plate from Mom to Lydia.

In summary, in the ‘on delivery’ phase of the object pass simpliciter, expressions of gratitude acknowledge the help in the passing of the object, and also indicate that the handover of the object is complete and the passer can let go. On-delivery expressions of gratitude are thus precisely coordinated with the action of object transfer, expressing gratitude while marking the manual handover.

We now examine expressions of gratitude that occur after the object has been picked up by the passer but before its actual transfer to the recipient. We find that these pre-delivery-positioned expressions of gratitude both acknowledge the assistance that has just happened and register the projected object transfer. Pre-delivery expressions of gratitude typically occur in contexts where the deliverer has engaged in some preparatory assistance before the object pass (such as searching for a requested item). Given participants’ orientations to contiguity and projectability of interaction (Sacks, 1987; Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson, 1974; Schegloff, 2007), the action performed by the expression of gratitude is shaped both by its immediately preceding context (i.e., acknowledging the preparatory assistance) and the projectable completion of upcoming object transfer.

For instance, in Extract 4, which takes place during breakfast, Irina is searching for the sugar and recruits others in finding it via the question “Where’s sugar¿” (line 1) (Drew & Kendrick, 2018). In response, both Eugene and Sofya visibly engage in a search for sugar (lines 2-4). Eugene then announces that he has found the sugar – “>R’t here<” (line 5) – and reaches for it in preparation for passing it over to Irina (line 6). Irina begins to reach for the sugar as she first acknowledges the finding of the sugar bowl with “Aoh” (Heritage, 1984), and then produces “Thank you” (line 7).

Open in a separate windowIn the course of line 6, Eugene picks up the sugar. Irina’s expression of gratitude occurs right before the manual transfer of the sugar bowl, when the sugar bowl is on its way to being delivered, i.e., when it is in a pre-delivery position. Here, it appears that the pre-delivery expression of gratitude acknowledges the assistance Irina receives in finding the sugar bowl and anticipates the physical passing of it. That is, the contiguity of the expression of gratitude to the finding of the object, and the projectability of its imminent delivery, provide for hearing the “thank you” as acknowledging his assistance in both finding the sugar and its delivery.

In Extract 5, Juan is asking his wife Ana for hot sauce. Ana is in the kitchen, off camera, but visible to Juan. Juan is sitting at the table with two guests. Juan announces, “Then let me get some ah: hot sauce¿” (line 1) and turns towards Ana in the kitchen. After a bit of silence in line 2, Juan confirms with Ana – “You have it?” (line 3) – that she has the hot sauce.

Open in a separate windowJuan begins to say “Tha::::nk you” (line 5) in the pre-delivery position as Ana starts to pass the hot sauce. In this way, the expression of gratitude is timed to acknowledge the preparatory work required to implement the delivery. However, Juan’s expression of gratitude is extended through a sound stretch on “Tha::::nk” so that its offset is also timed to coincide with the actual delivery. So, in this case “thank you” begins in the pre-delivery position and ends post-delivery, acknowledging both the preparatory assistance and coordinating the delivery. In line 7, Ana accepts the gratitude with “You’re ˚welcome.” – something that happens very rarely in our data (see also Floyd et al., 2018).

To summarize, the expressions of gratitude in the two cases above acknowledge both the assistance in locating the object and the projectable completion of the object transfer. Pre-delivery expressions of gratitude are produced when the object is on its way, but before it is received. The precise position of the expression of gratitude acknowledges both the immediately preceding assistance in finding the object and the anticipated passing of it.

Gratitude expressions can also occur after the recipient takes hold of the object. We find that post-delivery expressions of gratitude tend to occur after delivery announcements (e.g., here you are). The delivery announcement – as an announcement – makes a response conditionally relevant upon its completion (Schegloff, 2007). In our data, delivery announcements are responded to with expressions of gratitude. Since these announcements are produced during the object delivery (perhaps to alert the recipient to the delivery), the responsive expression of gratitude may end up being produced in a post-delivery position.

This is illustrated by Extract 6. Karen and her husband Nick are preparing to have dinner at a kitchen island. Nick offers to bring napkins (line 1) while Karen is cooking. Karen accepts Nick’s offer (line 3), and Nick walks to fetch the napkins (line 4). When he comes back, he hands a napkin to Karen (line 5) as she is sitting down at the kitchen island.

Open in a separate window Karen’s “Thank you” at line 6 occurs right after the delivery announcement and is produced slightly after the object transfer. Nick announces the delivery of the napkin as he is passing it to her (“There you are” in line 5). “Thank you” is produced at the earliest possible opportunity upon the completion of the delivery announcement. In this way, the expression of gratitude (“Thank you.”, line 5) is timed relative to both the physical delivery of the object and to its verbal announcement.Thus, when a delivery is announced at the moment at which an expression of gratitude could occur, the announcement prompts an expression of gratitude, which is now timed to be produced on its possible completion. Since many object passes go unacknowledged (in our data and as shown by previous studies; Floyd et al., 2018), delivery announcements – as an initiating action – may in fact occasion expressions of gratitude that might not have been produced otherwise, without drawing attention to their possible absence. Such post-delivery expressions of gratitude are still within the gratitude opportunity space – they acknowledge the service in an unremarkable (and unremarked-upon) way.

To summarize, we have shown that for assistance involving the passing of an object, the gratitude opportunity space is organized by reference to the embodied movement of the object from the person passing the object to the person receiving it. We documented three distinct phases during which expressions of gratitude are produced: pre-delivery, or timed to begin as an object is being lifted for a pass; on-delivery, or timed to coincide precisely with the onset of the pass of an object; and post-delivery, beginning after a recipient takes hold of an object. What precisely gets accomplished by the expression of gratitude is sensitive to its timing within this trajectory. Specifically, we have shown that ‘on-delivery’ expressions of gratitude manage the hand-off in addition to acknowledging the assistance; ‘pre-delivery’ expressions of gratitude acknowledge preparatory work and the anticipated object delivery, and ‘post-delivery’ expressions of gratitude respond to delivery announcements.

Thus far, we have examined expressions of gratitude produced within the trajectory of object pass simpliciter. These gratitude expressions are treated by participants as doing nothing special other than thanking for what is being passed. Next, we examine other kinds of activities involving an object pass to explore how the organization of activity configures the Gratitude Opportunity Space.

Object passing can be part of a larger course of action, such as offering something to be delivered later or giving gifts. By looking at other kinds of activities involving object passes, we find that the gratitude opportunity space dynamically recalibrates according to the activity underway.

For example, in Extract 7, the expression of gratitude produced before an object transfer is properly placed to appreciate the offer of the object that precedes its delivery. In this extract, Alex, the host of a gathering, is preparing to serve drinks to his guests. In lines 1-2, he offers alcoholic beverages to Dan and Misha. As Dan is American and Alex and Misha are Russian, this interaction takes place in both English and Russian. At line 2, Alex asks (in Russian) if Dan and Misha would like red or white wine or vodka:

Open in a separate windowIn response to Alex’s offer, both Dan and Misha ask for red wine (lines 4 and 5). Alex then re-asks Dan about his preference (line 6) and Dan reiterates his preference for red wine (line 8). Dan first appreciates Alex’s offer with “Red’s great” and then expresses his gratitude for the offer via “Thank you¿”. We can see here that the expression of gratitude occurs well before the wine is passed, and in this way, it acknowledges the offer itself rather than the delivery of the wine. Note that the offer of beverages here is a “remote” offer (cf. Lindström, 2017) since the service cannot be immediately provided (e.g., the drinks need to be poured, etc., unlike, for example, Extract 3 above). The gratitude opportunity space here is calibrated relative to the offer of a drink, rather than to the delivery of the drink. This remote offer opens up a space for expressing gratitude for the offer separately from expressing gratitude for the object. Later (data not shown), Dan produces a pre-delivery expression of gratitude (“Awesome. Thank you”) right before taking hold of the wine glass.

Next, we briefly explore the timing of gratitude expressions in the giving of gifts. People are ordinarily expected to thank gift-givers for the gift. While gift giving typically involves object transfer (i.e., passing of the gift from the giver to the recipient), the passing of the gift is only one component of the multiphase gift-giving activity. According to Good and Beach (2005), receiving a gift may involve (in some cultural contexts) the gift-receiver opening and announcing the gift to others, positively assessing the gift, and offering thanks to the gift-giver. Thus, gratitude can be produced substantially after the gift has been handed over – i.e., late by reference to the gift delivery – but appropriately positioned for this course of action. This means that the gratitude opportunity space is organized in relation to the overall activity of receiving the gift. In addition, a simple ‘thank you’ token may not be sufficient to show the gift-receiver’s gratitude. Recipients of a gift are expected to enact appreciation in addition to expressing gratitude by, for example, praising qualities of the gift (e.g., “That’s lovely”; see Robles, 2012) and/or articulating appreciation of the gift-giver (e.g., “That’s very kind of you”).

These observations are illustrated by Extract 8, taken from an interaction between Alex (the host) and several guests. Prior to this extract, the participants discussed electric toothbrushes. Marina said she wants to buy one to try. Apparently prompted by this revelation, Alex fetches an object from another room and proffers it to Marina without saying anything (data not shown). Marina asks what it is, taking the object from Alex (line 1). Then, as she identifies the object as a toothbrush, Marina expresses her appreciation (lines 3-5) and then gratitude for the gift (line 10).

Open in a separate windowMarina first enacts her appreciation by prosodically marking the recognition and identification of the object with “↑Oo↓:: (.) A t↑oo↓thbru:sh!=” (lines 3 and 5), and then expresses her excitement about the gift with “Ya:y.” (line 8). The gift-giver then modulates her expectations of the gift by saying “This is a si:mpler one.” (line 9). In overlap with the end of this turn, Marina produces an expression of gratitude, “Thank you.” (line 10). Here, Marina’s display of gratitude – enacting appreciation and saying ‘thank you’ – is temporally late by reference to the object pass; however, it properly follows her receipt of the gift.

This exploration of the timing of gratitude in remote offers and gift-giving suggests that the gratitude opportunity space is shaped by and calibrated to the ongoing interactional activities. Our observations highlight the importance of investigating the gratitude opportunity space as part of the ongoing course of action in which it is embedded, paving the way for further investigation.

5. Conclusions

We have introduced the concept of the gratitude opportunity space – a time period during which gratitude is routinely expressed. Through a close examination of recorded real-life instances of gratitude, we have shown that (and how) the gratitude opportunity space is sensitive to and calibrated against the affordances of the physical environment and the ongoing course of action. In the environment of the object pass simpliciter, we have shown the exact coordination of expressions of gratitude with the embodied action of object passing in three distinct phases within the gratitude opportunity space: pre-delivery, on-delivery, and post-delivery. Overall, we find that when expressions of gratitude are produced, they play an important role in the coordination of object passes. Additionally, we have shown that for other activities involving object passes (such as remote offers and gift giving), the gratitude opportunity space is calibrated to those activities. Starting with cases where relatively small-scale services were delivered in real time by co-present parties allowed us to explicate the exquisitely precise timing of these practices of giving thanks. Our findings suggest interesting directions for future research on expressions of gratitude: the possibility for the normative organization of the gratitude opportunity space, the possible distinction between appreciation and gratitude, and turn design in expressions of gratitude.

We have not argued that gratitude opportunity space is a normative organization, but, rather, that the precise timing of expressions of gratitude in cases of object transfer accomplishes important interactional work. However, there are indications that it is possibly normatively organized, at least for some types of activities. For instance, evidence for participants’ orientation to the normative character of the gratitude opportunity space comes from cases in which interlocutors pursue a ‘missing’ expression of gratitude. For example, in interactions with children, parents may prompt expressions of gratitude when they are not produced within the gratitude opportunity space, using such prompts as “What’s the magic word?” or “What do you say?” (Gleason & Weintraub, 1976; Gleason et al., 1984). Furthermore, interlocutors may apologize for a late articulation of gratitude, thereby constituting their gratitude expression as having been produced outside the gratitude opportunity space. The following two cases provide a brief illustration of these points.

In Extract 9, Mom, Dad, Amanda (age 6), Nathan (age 10), and a foreign exchange student Valerie (age 17) are having dinner. Amanda requests more asparagus from her Mom (lines 1-2). Mom grants the request (line 5), but before she can comply with it, Valerie puts the plate of asparagus in front of Amanda (line 6). Amanda then starts to reach for a piece of asparagus (line 6). As she does so, Mom prompts an expression of gratitude with “Whaddya say?” (line 7). Amanda complies with “Thank you.” (line 9) as she takes a piece of asparagus off of the plate in front of her.

Open in a separate windowIn this case, we can see that Mom treats an expression of gratitude as relevant and missing after Valerie’s delivery of the plate of asparagus (line 6). Mom thus orients to the gratitude opportunity space as having passed after the placement of the plate.ii This is evidenced by the timing of Mom’s prompt: as Amanda is reaching for the asparagus, but after the plate has been set down in front of her. The expression that Mom uses (“Whaddya say?”; line 7) draws attention to the problem (not saying something), which can only be done after it is clear that there is a problem (not saying something). Mom’s prompt indicates that Amanda missed her chance to thank Valerie during the gratitude opportunity space.

The possible normative organization of the gratitude opportunity space is also evident in the following case (Extract 10). Although this case does not include an object transfer like our other cases, it nonetheless suggests that there is a normative time period for expressing gratitude. This case is from a telephone conversation between two friends, Edna and Margie. Following a discussion of another topic (data not shown), Edna expresses appreciation for a social event held by Margie approximately a week ago, characterizing it as “lovely” and “deli:ghtfu:l.” (lines 5-6). As part of her turn, Edna displays an orientation to the lateness of her call: “I shoulda ca:lled you s:soo:ner”, indicating that that there is a normative time period for showing gratitude in this type of social activity.

Open in a separate windowBy formulating the timing of her call as a transgression (Drew, 1998; Schegloff, 2005), Edna shows her orientation to the lateness of her gratitude. She subsequently re-invokes the transgression (lines 41-43), again indicating that she understands her call to have been made later than it should have been. This extract suggests that for this particular activity, being hosted at a social event, the gratitude opportunity space may be organized by reference to the time elapsed since the event. This is not to say that there is an “objective” measure of time during which gratitude should be expressed. Rather, the formulation of gratitude (with the included acknowledgement of its lateness) reflexively constructs her gratitude as late, and in doing so indexes a normative expectation for its timing (which has now been violated).

Extracts 9 and 10 point to a normative organization of the gratitude opportunity space – i.e., gratitude expressions outside the gratitude opportunity space may be treated as accountably ‘late’ or missing. Future work could examine further the extent to which this gratitude opportunity space is normative: is there a normative expectation to express gratitude during the gratitude opportunity space, or is it, as we have framed it, simply a place where there is an opportunity for gratitude?

Our analysis also points to participants’ distinction between appreciation and gratitude. For instance, appreciation and assessments are commonly seen in gift-giving sequences (e.g., Extracts 7 and 8), where they may precede expressions of gratitude, but not in object pass simpliciter. This develops our understanding of what counts as gratitude (versus appreciation) and how it is sensitive to the kind of activity that is being thanked for. By building on this research, the way in which thanks and appreciation may serve different roles could become clearer.

This paper also raises issues of turn design in expressions of gratitude. We might expect that “larger” or more elaborate gratitude will be provided for “larger” services (cf. Heritage & Raymond (2016) on proportionality between apology and offense). However, at least for simple object passes, the elaborateness of the gratitude expressions seems to be primarily related to the coordination of the pass of the object. For instance, in Extracts 2 and 5, gratitude expressions are extended with address terms (“thanks gram” and “Tha::::nk you Ana,”, respectively), which are timed to precisely to object passes in these segments. Future research could examine turn design features of gratitude expressions, such as terms of endearment or other address terms, that may manage a range of social interactional contingencies. This study lays the groundwork for exploring the timing of gratitude in more complex activities.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their feedback that has helped improve this manuscript. All shortcomings remain our own.

References

Algoe, S. B., Fredrickson, B. L., & Gable, S. L. (2013). The social functions of the emotion of gratitude via expression. Emotion, 13(4), 605-609.

Algoe, S. B., Gable, S. L., & Maisel, N. C. (2010). It's the little things: Everyday gratitude as a booster shot for romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 17(2), 217-233.

Bartlett, M. Y., & DeSteno, D. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behavior: Helping when it costs you. Psychological Science, 17(4), 319-325.

Blum-Kulka, S. (1990). You don’t touch lettuce with your fingers: Parental politeness in family discourse. Journal of Pragmatics, 14(2), 259-288.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage (Vol. 4). Cambridge University Press.

Clankie, S. M. (1993). The use of expressions of gratitude in English by Japanese and American university students. Kenkyu Ronshu/Journal of Inquiry and Research, 58, 37-71.

Clayman, S. E. & Heritage, J. (2014). Benefactors and beneficiaries. In P. Drew & B. Couper-Kuhlen (Eds.), Requesting in social Interaction (pp. 55-87). John Benjamins.

Coulmas, F. (1981). Poison to your soul: Thanks and apologies contrastively viewed. In F. Coulmas (Ed.), Conversational routine: Explorations in standardized communication situations and prepatterned speech (pp. 69-91). Mouton Publishers.

Drew, P. (1998). Complaints about transgressions and misconduct. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 31(3-4), 295-325.

Drew, P., & Kendrick, K. H. (2018). Searching for trouble: Recruiting assistance through embodied action. Social Interaction: Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 1(1). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7146/si.v1i1.105496

Due, B., & Trærup, J. (2018). Passing glasses: Accomplishing deontic stance at the optician. Social Interaction: Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 1(2). DOI: 10.7146/si.v1i2.110020

Eisenstein, M., & Bodman, J. W. (1986). “I very appreciate”: expressions of gratitude by native and non-native speakers of American English. Applied Linguistics, 7(2), 167-185.

Eisenstein, M., & Bodman, J. (1993). Expressing gratitude in American English. In G. Kasper & S. Blum-Kulka (Eds.), Interlanguage pragmatics (pp. 64-81), Oxford University Press.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: an experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377-389.

Floyd, S., Rossi, G., Baranova, J., Blythe, J., Dingemanse, M., Kendrick, K. H., ... & Enfield, N. J. (2018). Universals and cultural diversity in the expression of gratitude. Royal Society Open Science, 5(5), 180391.

Garcia, C. (2016). Peruvian Spanish speakers’ cultural preferences in expressing gratitude. Pragmatics, 26(1), 21-49.

Gleason, J. B., & Weintraub, S. (1976). The acquisition of routines in child language. Language in Society, 5(2), 129-136.

Gleason, J. B., Perlmann, R. Y., & Greif, E. B. (1984). What's the magic word: Learning language through politeness routines. Discourse Processes, 7(4), 493-502.

Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction Ritual: Essays in Face to Face Behavior. Doubleday.

Good, J. S., & Beach, W. A. (2005). Opening up gift-openings: Birthday parties as situated activity systems. Text, 25(5), 565-593.

Gordon, A. M., Impett, E. A., Kogan, A., Oveis, C., & Keltner, D. (2012). To have and to hold: Gratitude promotes relationship maintenance in intimate bonds. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(2), 257-274.

Greif, E. B., & Gleason, J. B. (1980). Hi, thanks, and goodbye: More routine information. Language in Society, 159-166.

Heath, C., Luff, P., Sanchez-Svensson, M., & Nichols, M. (2018). Exchanging implements: The micro-materialities of multidisciplinary work in the operating theatre. Sociology of Health & Illness, 40(2), 297-313.

Hepburn, A., & Bolden, G. B. (2017) Transcribing for Social Research. Sage.

Heritage, J. (1984). A change-of-state token and aspects of its sequential placement. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 299-345). Cambridge University Press.

Heritage, J., & Raymond, C. W. (2016). Are explicit apologies proportional to the offenses they address? Discourse Processes, 53(5), 5-25.

Kendrick, K. H., & Drew, P. (2016). Recruitment: Offers, requests, and the organization of assistance in interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 49(1), 1-19.

Kendon, A. (1982). Some relationships between body motion and speech: An analysis of an example. In A. W. Siegman & B. Pope (Eds.), Studies in dyadic communication (pp. 177-210). Pergamon Press.

Kendon, A. (1980). Gesticulation and speech: Two aspects of the process of utterance. In M. R. Key (Ed.), The relationship of verbal and nonverbal communication (pp. 207-227). Mouton Publishers.

Kita, S., Van Gijn, I., & Van der Hulst, H. (1997). Movement phases in signs and co-speech gestures, and their transcription by human coders. Gesture and Sign Language in Human-Computer Interaction, 22-35.

Lambert, N. M., Clark, M. S., Durtschi, J., Fincham, F. D., & Graham, S. M. (2010). Benefits of expressing gratitude: Expressing gratitude to a partner changes one’s view of the relationship. Psychological Science 21(4), 574-580.

Lerner, G. H., & Raymond, G. (2017). On the practical re-intentionalization of body behavior: Action pivots in the progressive realization of embodied conduct. In G. Raymond, G. H. Lerner & J. Heritage (Eds.), Enabling human conduct: Studies of talk-in-interaction in honor of Emanuel A. Schegloff (pp. 299-313). John Benjamins.

Lindström, A. (2017). Accepting remote proposals. In G. Raymond, G. H. Lerner & J. Heritage (Eds.), Enabling human conduct: Studies of talk-in-interaction in honor of Emanuel A. Schegloff (pp. 125-142). John Benjamins.

McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect?. Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 249.

McCullough, M. E., & Tsang, J. (2004). Parent of the virtues? The prosocial contours of gratitude. In R. A. Emmons, & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp.123-141). Oxford University Press.

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85-106.

Okamoto, S., & Robinson, W. (1997). Determinants of gratitude: Expressions in England. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 16(4), 411-433.

Raymond, G., & Zimmerman, D. H. (2016). Closing matters: Alignment and misalignment in sequence and call closings in institutional interaction. Discourse Studies, 18(6), 716-736.

Robles, J. S. (2012). Troubles with assessments in gifting occasions. Discourse Studies, 14(6), 753-777.

Martínez Robledillo, N. (2015). Thanking formulae in English and Spanish: A pilot study [Thesis]. University of Jaén Theses Repository. http://tauja.ujaen.es/bitstream/10953.1/1997/1/MARTIN~1.PDF

Sacks, H. (1987). On the preferences for agreement and contiguity in sequences in conversation. In G. Button & J. R. E. Lee (Eds.), Talk and social organisation (pp. 54-69). Multilingual Matters.

Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures on conversation. Blackwell Publishing.

Sacks, H., & Schegloff, E. A. (2002). Home position. Gesture, 2(2), 133–146.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., Jefferson, G., & (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696-735.

Schegloff, E. A. (1987). Analyzing single episodes of interaction: An exercise in conversation analysis. Social Psychology Quarterly, 50(2), 101-114.

Schegloff, E. A. (2005). On complainability. Social Problems, 52(4), 449-476.

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction: A primer in conversation analysis. Cambridge University Press.

Schegloff, E. A., & Sacks, H. (1973). Opening up closings. Semiotica, 8(4), 289-327.

Sidnell, J., & Stivers, T. (Eds.). (2013). The handbook of conversation analysis. Wiley-Blackwell.

Tuncer, S., & Haddington, P. (2020). Object transfers: An embodied resource to progress joint activities and build relative agency. Language in Society, 49(1), 61-87.

Williams, L. A., & Bartlett, M. Y. (2015). Warm thanks: Gratitude expression facilitates social affiliation in new relationships via perceived warmth. Emotion, 15, 1-5.

Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. W. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 890-905.

Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., Lloyd J., & Atkins, S. (2009). Gratitude influences sleep through the mechanism of pre-sleep cognitions. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 66(1), 43-48.

Woods, C. J., Drew, P., & Leydon, G. M. (2015). Closing calls to a cancer helpline: Expressions of caller satisfaction. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(8), 943-953

Zimmerman, D. H., & Wakin, M. (1995, August). Thank you’s and the management of closings in emergency calls [Paper presentation]. 90th Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association, Washington, DC.

Zinken, J., Rossi, G., & Reddy, V. (in press). Doing more than expected: Thanking recognizes another’s agency in providing assistance. In C. Taleghani-Nikazm, E. Betz, & P. Golato (Eds.), Mobilizing others: Grammar and lexis within larger activities. John Benjamins.

i There are, of course, object passes where expressing gratitude is not relevant – such as when the recipient of the object does not benefit from it. These are beyond the scope of our study.

ii Note that this is a placement of an object, which is different from a pass.