Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Companion Involvement as a Practice for Addressing Patient Resistance:

The Case of Traditional Chinese Medicine

Wan Wei

Pennsylvania State University, Abington College

Abstract

Previous research highlights how the presence of companions can influence the trajectory and outcome of medical encounters. This study, set within the context of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), examines cases where medical professionals enlist patient companions to join the consultation when patients resist the doctors' medical opinions. Results from this study indicate that when companions participate in this manner, they face the dilemma of either endorsing the doctors and aiding in the implementation of their medical agenda or siding with the patients and being a supportive companion. This may explain why this practice is not always effective in countering patient resistance and securing patient adherence, especially when the patient's resistance is overt and strong.

Keywords: Triadic medical interaction, provider-patient communication, alternative medicine, conversation analysis

1. Introduction

Although often perceived as peripheral participants in provider-patient interactions, companions of patients can, in fact, fulfill essential and transformative roles. Past research has discovered that companion participation is relevant to many aspects of healthcare services, including patients' involvement in the shared decision-making process (Clayman et al, 2005), patients' level of satisfaction with the care received (Wolff & Rotter, 2008), and patients' adherence to their medical regimen (DiMatteo, 2006). The presence of companions is prevalent in Chinese hospitals, as it is a cultural norm in China for patients to attend medical appointments accompanied by someone, typically their spouses, adult children, friends, or even coworkers (Wei, 2021; Yan & Yang, 2024; Yang et al., 2018). Additionally, the concept of privacy is interpreted differently in Chinese medical culture, resulting in medical consultations being relatively open and informal interactions where even bystanders can join in and participate (Wei, 2024). This unique characteristic of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) encounter makes it an ideal site for studying companion involvement. In this study, I examine a specific type of companion participation that occurs when patients display resistance to doctors' treatment recommendations or lifestyle advice. In such instances, companions are enlisted by the doctors to offset patient resistance and assist doctors in achieving institutional goals.

2. Literature Review

Health communication researchers have long been interested in exploring the significant impact that companions have on medical consultations. Previous research has explored different aspects of companion participation, such as the roles that companions play (Adelman et al., 1987; Ellingson, 2002; Vick et al., 2018); different forms of support that companions are able to offer (Laidsaar-Powell et al.,2013; Wolff & Roter, 2012), as well as individual differences that may shape patients' experiences of companion involvement. These factors include cultural context (Ishikawa et al., 2005; Tsai, 2007), racial differences (Wolff & Roter, 2012), and the patient's communication style (Werner, Gafni, & Kitai, 2006).

Although these studies offer great insight into communication dynamic of companion involvement, more research is needed to examine this issue "in situ", through an interaction-focused lens. Scholars within the field of language and social interaction have looked at companion involvement occurring in different interactional contexts, including pediatric visits (Clemente, 2009; Stivers, 2002, 2005, 2007), interpreter-mediated consultations (Bolden, 2000; Hsieh, 2007); neurological/rheumatological visits (Fioramonte &Vásquez, 2019) and palliative care (Pino et al., 2024). There has also been a substantial body of research on companion participation in medical interactions that involve patients with intellectual challenges (Antaki & Chinn, 2021; Chinn, 2022; Mikesell, 2009; Solomon et al., 2016). Additionally, scholarly attention has also turned to companion participation in online medical consultations (Stommel & Stommel, 2021). However, there remains a notable gap in the exploration of companion participation in alternative medicine, despite the frequent involvement of companions in this context (Wei, 2024).

One important issue discussed in companion participation research is that companions must navigate and negotiate coalitions during medical visits. They can either support the doctors' projects or side with the patients. For example, Adelman et al. (1987) discussed how some companions can adopt the role of antagonists and undermine the medical agenda. This phenomenon is also investigated in conversation analytic research, where researchers have outlined the potential relational and interactional implications of divergent positions between patients and companions (Pino et al., 2021; Pino & Land, 2022).

The current study addresses an important gap in the literature on companion participation, focusing specifically on TCM encounters. Companion roles have been explored in Western medical contexts, where companions often negotiate alliances that may either support or conflict with the goals of healthcare providers. Adelman et al. (1987) illustrated how companions could sometimes adopt an antagonistic role, potentially challenging the medical agenda. Similarly, conversation analytic research (Pino et al., 2021; Pino & Land, 2022) has examined the complex relational implications that arise when companions' positions diverge from those of patients, revealing both relational and interactional nuances that can impact communication dynamics.

In TCM, however, companion participation may take on unique forms influenced by cultural norms, the informal nature of the consultations, and the common practice of having companions accompany patients. Unlike Western medical contexts, TCM consultations often foster a more holistic, interpersonal approach to health, in which companions may feel more empowered to engage actively in the interaction. This cultural difference may not only alter the nature of patient-companion alliances but also influence how companions position themselves in relation to both the patient and the provider.

By situating this research in TCM encounters, the current study seeks to provide a nuanced understanding of how companion roles and relational dynamics vary across cultural medical contexts. The findings have the potential to expand our understanding of companion involvement beyond Western medical frameworks, illustrating how TCM's holistic and often collaborative approach may foster distinct patterns of negotiation and coalition-building. Ultimately, this study contributes to the broader field of health communication by highlighting how cultural variations in medicine influence patient-companion-provider interactions and by offering insights into the relational dynamics unique to TCM.

3. Data and Methods

The data segments analyzed in this study were drawn from a data corpus comprising approximately 51 hours of video-recorded interactions between TCM practitioners and patients during naturally occurring TCM consultations. The recordings were collected in two TCM hospitals situated in a major city in eastern China. One hospital is affiliated with a local TCM university, while the other is privately owned. The data collection involved the active participation of two TCM practitioners. These recordings, supplemented by extensive ethnographic notes documenting the intricacies of the interactions, were accumulated by the author over a period of four years (2014-2017). The project was approved by the relevant institutional review board (XXXX IRB #E15-184).

In total, this study encompasses a dataset consisting of 21 recordings, which yielded 109 complete TCM visits. The data segments were transcribed following the Jeffersonian convention (Jefferson, 2004; Hepburn & Bolden, 2017) and subsequently analyzed using conversation analysis (Sidnell & Stivers, 2012). After going through the data collection, I was able to identify 39 cases of the target phenomenon.

A brief introduction to TCM encounters is warranted to provide additional background information. TCM encounters share a similar overall structural organization with primary care visits (Robinson, 1998; 2003), but with three distinct features. First, many TCM visits lack a "presenting concern" (Heritage & Robinson, 2006). Since most TCM consultations are routine, patients do not always bring specific medical concerns. Instead, the majority of TCM cases in my collection begin with the activity of "pulse-taking" (Wei, 2021). Second, lifestyle discussions tend to be extensive in TCM visits, as lifestyle adjustments are part of the TCM treatment regimen. It is common for doctors to alternate between recommending treatment (medicine) and giving lifestyle advice, because the effectiveness of TCM medicine relies heavily on enforcing certain lifestyle rules. Third, and particularly relevant to the current study, is the frequent observation of patient resistance in TCM encounters. Several factors may contribute to this phenomenon, such as the opacity of TCM diagnosis/treatment, the informal, long-term relationship between TCM doctors and patients, and the prevalent lifestyle discussions that occur in TCM encounters.

4. Analysis

Companion participation in TCM consultations can occur in two ways: either companions join spontaneously or upon the doctor's invitation. This study specifically focuses on the latter, examining instances where companions become part of the ongoing consultation after being involved by the doctor. I demonstrate how doctors can enlist companions to help address patient resistance and facilitate the medical agenda. However, this practice is not always effective. Out of the 39 cases I examined, only 11 were successful, with companions agreeing to offer doctors assistance in implementing the recommended lifestyle advice. In the remaining 28 cases, companions choose to be on the patients' side and decline to offer the help that the doctor has requested.

In this section, I examine two cases of enlisted companion participation. The first segment, Extract 1, is a successful case, in which the patient's resistance is tacit (withholding acceptance). When the patient's companion is invited to join the consultation and assist in implementing the recommended lifestyle change, she quickly accepts the responsibility. Conversely, Extract 2 presents a failed case where the patient's companion sides with the patient and partially rejects the doctor's advice. In this case, patient resistance is stronger and much more overt. In presenting these two cases, I demonstrate the delicate position companions may find themselves in when asked to help implement the doctor's medical agenda. Companions must decide whether to support the patients in their resistance or to affiliate with the doctors to ensure the successful implementation of medical advice. They are confronted with two conflicting sets of concerns: the relational concern of maintaining a united front with the patient and the medical concern of achieving the goals of the medical visit.

4.1 Companion supporting the doctor's line of action

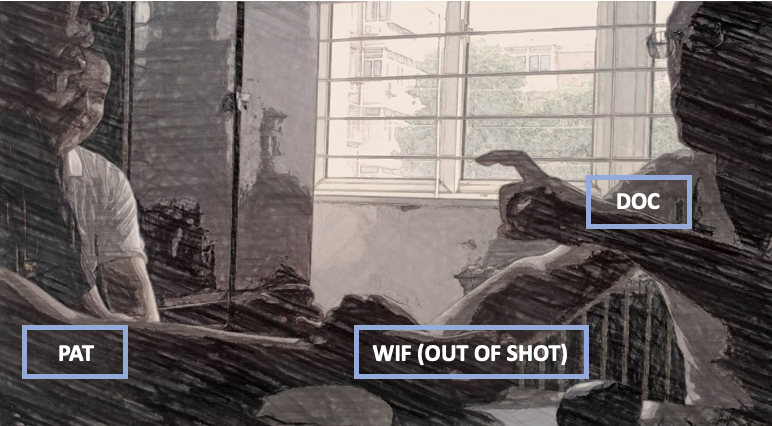

Extract 1 shows a case of successful enlistment, where the patient's companion agrees to help the doctor implement the recommended dietary changes. The patient, a man in his 50s, regularly visits the doctor and is accompanied by his wife (Fig. 1). This segment takes place after the doctor has prescribed TCM medicine and is now discussing necessary lifestyle changes to enhance treatment effectiveness. In this extract, the patient's resistance is subtle, as he merely withholds acceptance of the doctor's recommendation by staying silent and producing "noncommittal", minimal responses. The wife is enlisted by the doctor after the patient's continuous resistance to ensure that the patient consumes a specific food item daily to improve his overall health.

| Patient information | |

|---|---|

| Patient Sex | Male |

| Patient Age | 50s |

| Type of visit | Routine visit |

| Companion(s) | Wife |

| Medical activity | Lifestyle discussions |

Figure 1.

Extract 1. Big temper.

Open in a separate windowThis extract begins with the doctor making a dietary recommendation that the patient should change his eating habit. This advice is delicate, as both the patient and his wife are from Tianjin, a place renowned for its delicious but unhealthy food, while the doctor is not. The doctor carefully formulates his recommendation to acknowledge its delicateness: first, he simply names "Tianjin food" (line 3), leaving the patient to infer its relevance; then, he includes a disclaimer in line 5, "Although you are from Tianjin. (0.2) I mean no disrespect," framing his forthcoming advice as potentially disrespectful.

After the patient accepts the disclaimer (line 8), the doctor proceeds with his recommendation. He begins with a general, nonspecific suggestion: "Em, you definitely should make some changes" (lines 9 & 10). The doctor then provides an account for this recommendation: "Health maintenance starts from lifestyle choice" (line 12). This account, offered before the specific advice, is framed as a truism, encapsulating fundamental TCM principles that link the patient's health status to their lifestyle choices. This account, offered before the specific advice, is framed as a truism, encapsulating fundamental TCM principles that link the patient's health status to their lifestyle choices. It is used here as potential evidence to shore up the doctor's lifestyle advice. The long gap at line 13 may suggest a potentially dispreferred response from the patient. In line 14, the doctor pursues acceptance from the patient by reinforcing his argument and presenting lifestyle change as the only viable option: "Otherwise, what else can you do to maintain your health?". This time, the patient responds, but only with a multiple saying in line 15: "Right, right, right."

As Stivers (2004) argued, multiple sayings like this can be resistant and dismissive, as they treat the prior course of action as unnecessarily persistent. This may explain why the doctor formulates an extreme case (Pomerantz, 1986) in lines 16-18, claiming that the patient's condition will not improve without the proposed change, even if the patient were to adopt the most extreme form of asceticism, such as living as a monk. This extreme case formulation may be understood as another attempt from the doctor to secure stronger acceptance from the patient, but it only receives a lukewarm "Oh", at line 19. This change-of-state token (Heritage, 1984) registers the doctor's turns as new information, but it may constitute an insufficient response to the doctor's recommendation. The doctor clearly orients to it as such, given his further pursuit in line 20: "Isn't that right. No?". Once again, this pursuit is met with tacit resistance from the patient (gap in line 21).

The patient's tacit yet continuous resistance may explain why the doctor shifts his focus in line 22 to address the patient's companion, his wife. He directs his gaze toward her and instructs her to cook a specific food item for the patient: "From now on, one meal every day must be rice porridge." This order is framed as an absolute necessity, as indicated by the word "must" in line 23.

The doctor's turn is not immediately responded to by the wife (gap in line 24). At line 25, she seeks confirmation from the doctor regarding his recommendation in line 23 by repeating the suggested food item: "Rice porridge?" This repetition, delivered with rising intonation, prompts a confirming or disconfirming response from the doctor. By checking her understanding of the recommendation, the wife treats it as unexpected or surprising (Robinson, 2013; Robinson & Kevoe-Feldman, 2010), maybe due to its simplicity.

In response, the doctor confirms that porridge is indeed the recommended food item with a simple "Yep" (line 26). In line 28, after a brief gap, the doctor redelivers his recommendation, followed by an explanation why this dietary change is necessary. He directs the wife's attention to a specific clinical sign the patient is manifesting, small wrinkles on his face (lines 30 to 34), juxtaposing both verbal and embodied actions (turning the patient's face, pointing). In lines 36 and 37, he promises that the proposed treatment—daily rice porridge—will successfully address the issue. Potentially occasioned by this promise, in line 38, the wife agrees to adopt this change and prepare the food item ("Okay sounds good"). She then asks for specific instructions on how to prepare the recommended food item, "Wh- What kind of rice? porridge?" (line 40). The doctor provides further guidance in line 41, continuing through lines 43 to 45 and then again in lines 47 to 49, explaining the necessity of the dietary change by giving negative evaluations of both the patient's external physical appearance and internal health status.

The wife strongly agrees with the doctor's medical opinions in line 46: "That's right" and then again line line 51: ".Hheheheh. Yeh. You are totally right". She even corroborates the doctor's claims and issues a complaint about the patient: "At home he is very overbearing". In response, the doctor offers a simplistic solution in line 53 to 54: ".Hheheheh no matter how overbearing he is as soon as you cry, he won't have a way".

This extract showcases how doctors involve patients' companions when faced with patient resistance. Prompted by the patient's unenthusiastic, noncommittal responses to his lifestyle advice, the doctor changes tactics and begins addressing the patient's wife instead. While his advice to the patient is general (making dietary changes), his instructions to the wife are more specific, detailing the food preparation method (cooking rice porridge). In this way, the doctor invokes the wife's identity as the food provider of the family. The doctor, by targeting the wife instead, treats his advice as something that requires joint effort from the couple. When the patient's acceptance is lacking, the doctor turns to his wife to ensure his medical agenda is successfully advanced. Here, the doctor succeeds - although the patient never embraces his recommendation, his wife agrees to implement the dietary change.

However, not all doctors succeed when they choose to use this kind of "flanking maneuver". In the following section, I demonstrate how a companion, after being enlisted by the doctor, supports the patient in instances of overt patient resistance.

4.2 Companion supporting the patient's resistance

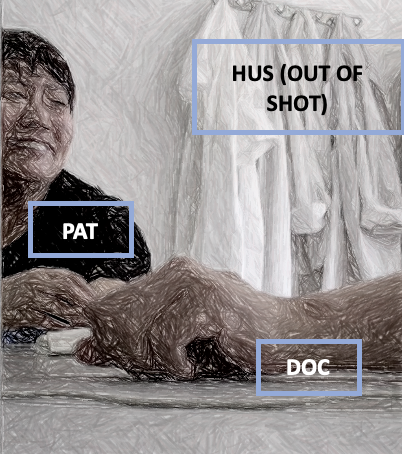

Extract 2 presents another case of companion participation, but this time the doctor's attempt is unsuccessful. In this extract, the doctor involves the patient's husband in the consultation after the patient has shown strong and overt resistance to the doctor's lifestyle advice. The patient in this extract is a 52-year-old woman. Prior to this extract, she was diagnosed with the condition of excessive dampness and heat1, a very common problem among middle-aged women. Her treatment regimen includes medicinal soup and several lifestyle changes, with weight loss being a key component. The extract begins with the doctor explaining to the patient what "excessive dampness and heat" can do to her body.

| Patient information | |

|---|---|

| Patient Sex | Female |

| Patient Age | 52 |

| Type of visit | Routine visit |

| Companion(s) | Husband |

| Medical activity | Lifestyle discussions |

Figure 2.

Extract 2.

Open in a separate windowIn lines 1-4, the doctor reports some possible symptoms that the patient may be experiencing as a result of her health problem. In line 5, the doctor raises another concern about the patient's overall health, her lack of physical activity: "And (you) are also very lazy and don't like to move". He attributes the patient's lethargy to her lack of muscle mass in lines 7, 9, and 10. At line 8, when the doctor's turn (line 8) is still in progress, the patient issues a complaint: "I feel uncomfortable all over", implying that her lack of physical activity may be a result of her poor health, rather than her lack of muscle. The doctor does not acknowledge the patient's complaint and continues to explain the physiological mechanism behind her lethargy in lines 9-12, which receives an agreement from the patient (line 13).

It can be argued that, up until now, by linking the patient's medical problem with her lack of muscle mass, the doctor is setting the stage for his upcoming lifestyle advice of urging the patient to be more physically active. In line 16, he launches this advice: "Can we transform the fat a little?" Several observations can be made about the doctor's turn here. First, the advice is framed as a question, inviting a yes or no response from the patient. The successful implementation of the doctor's treatment regimen is contingent upon the patient's acceptance and cooperation. Second, the use of the Chinese particle "Xia" (which can be translated as "quickly" or "a bit") minimizes the perceived effort required from the patient to implement this lifestyle change. Third, the doctor employs the institutional, collective "we", presenting this advice as a collaborative effort that requires joint participation from both parties (the doctor and the patient). The design of the doctor's turn speaks to the delicate nature of his advice, since it carries the implication that the patient may be overweight, something that may be perceived as potentially face-threatening to the patient.

The patient in line 17 to 18 quickly declines the doctor's proposal. She expresses willingness to adopt the prosed change but also claims inability to follow through: "I want to transform it. But I don't have the ability at all". The patient's resistance here is very explicit - it acknowledges the validity of the doctor's advice, but at the same time, rejects it in totality - since she does not possess the capability of executing it, there is no way she can adopt the doctor's proposal.

After the patient's resistant move, the doctor begins to enlist her husband. He delivers his specific recommendation at line 19 and 20, suggesting that the patient should follow her husband's actions and engage in more physical activity ("Learn something from that old dude. You need to exercise every day"). In doing so, the doctor positions the husband as a role model, suggesting that the patient should follow his example. The way the doctor refers to the patient's husband ("that old dude") suggests familiarity and intimacy, since "laoger (old dude, old brother)" is an address term used only by close friends. By using this address term, the doctor is enacting being close to the patient's husband, which may be construed as an attempt to draw the husband into a coalition with him. This is a strong piece of advice since the doctor uses the word "need" which indicates that the doctor is recommending something essential to the patient. Produced after the patient has already displayed resistance towards his earlier, softened proposal, this specific advice about how to "transform fat" provides another opportunity for the patient to accept the doctor's advice. While the doctor's turn is still in progress, the patient in lines 21 and 22 rejects the doctor's advice, by repeating her prior response and once again claiming inability to follow through. The patient's rejection sustains her resistant stance towards the doctor's lifestyle advice and indicates that instead of home remedy, she may be looking for medical intervention ("I need your help"). Her request for help receives a straight "no" from the doctor. He then once again engages the husband, this time by directly addressing him (the summons "Mr. Li" at line 23). After receiving the husband's response ("Yep" in line 24), the doctor instructs him to train his wife in some form of "support." In formulating his instruction in this ambiguous way, the doctor treats the husband as knowledgeable about exercising and thus able to infer what is meant by "that support". This reinforces the doctor's earlier attempt to present the husband as a role model for the wife—someone who can assist her in achieving her health goals. In line 26, the doctor, as an afterthought, checks the husband's ability to perform this form of exercise: "Can you (perform that exercise)?". As indicated by the gap at line 27, the answer is likely to be a dispreferred "no"—either because the husband is unfamiliar with the exercise or because he does not recognize what the doctor is referring to. In line 28, the doctor further unpacks what he meant by "that support" by giving more detailed instructions. Note that when this is happening, the patient turns her head away and produces a sigh, which clearly conveys the patient's negative stance towards the doctor's ongoing course of action (Hoey, 2014). In line 31, the doctor finally recalls the official name of the exercise (plank), while the husband, in overlap, gives a candidate answer (line 32, "Pushup?"). This apparently wrong candidate term is corrected by the doctor at line 33 when he repeats the proper name of the exercise: "plank", accompanied by some bodily gestures to simulate the movement of plank (line 34).

In response, the husband reports his experience with the plank (line 35, "I often do it"). In producing this report, the husband shows that he not only knows about this exercise, but also has experience practicing it. Additionally, in the following turns, he demonstrates knowledge about this exercise by highlighting that one's body must be in good condition to practice the plank (lines 39 to 40). The husband's turn here may be an implicit rejection of the doctor's advice, as it was previously established in the consultation that the patient's body is not "in good shape". When the doctor persists (line 41), the husband suggests an alternative form of exercise at lines 43-44 —power walking in the park, an activity he and the patient already do regularly. However, the patient remains adamant in her resistance to the doctor's advice (line 45), citing insufficient time. She even gives herself a negative assessment at line 47 ("Not good"), accompanied by laughter tokens. Possibly influenced by his wife's firm opposition, the husband partially retracts his previous proposal in lines 48, 50, and 51, making it conditional: "When you feel tired, you don't have to (power walk)". However, as lines 49 and 51 indicate, the doctor also maintains his stance towards his lifestyle advice. He offers encouragement in line 54 ("Don't let yourself be defeated") and pursues a response from the patient at line 55 ("You know?"). The doctor's turns are met with another resistant move from the patient: "Tsk.. Hhh. No I am really not good, I'm really good.". After this, the doctor moves on to address another medical concern (back pain) that the patient raised earlier, officially closing the discussion about the patient's level of physical activity.

The patient resistance in this extract is overt and stronger, with the patient directly rejecting the doctor's advice and giving different accounts for the rejection. When confronted with patient resistance, the doctor in this extract utilizes the patient's companion as a resource to mitigate the resistance and restore the progressivity of the medical visit. Instead of continuing to seek the patient's acceptance, the doctor takes a different route and enlists the companion, someone who can assist in implementing the lifestyle change that the doctor has proposed. However, after initially displaying knowledge of and experience in the exercise recommended by the doctor, suggesting he has the ability to implement the doctor's proposal, the companion joins his wife in resisting the doctor's advice. He first nominates an alternative to the recommended exercise and then further retracts his previous stance, ultimately affiliating with the patient.

By enlisting the husband as the "personal trainer" for the patient, the doctor treats his lifestyle advice as a joint activity that involve both the patient and her companion. It also puts the husband in the position to choose sides. Given the patient's resistance to the doctor's advice, if the husband agrees to help the doctor train the patient, he places himself in the same coalition with the doctor. Conversely, if he declines to help, he risks being part of the "opposition party" that prevents the doctor's medical agenda from advancing. In this extract, the husband ultimately sides with his wife and retracts his support for the doctor's medical advice. In addition to the stronger level of resistance displayed by the patient, another notable difference between Extract 2 and Extract 1 is the nature and scope of the assistance requested by the doctor. In Extract 1, the doctor asks the companion to prepare rice porridge for the patient each day. This request requires effort but does not directly involve intervening in the patient's actions; while the companion can prepare the food, it is ultimately up to the patient to choose to eat it. In contrast, the request in Extract 2 is "bigger" in both responsibility and interactional demand, as it calls for the companion to actively "train" his wife in an exercise practice. Here, the doctor is asking the companion to take on a more directive role, essentially becoming an agent of the doctor at home, directly overseeing and managing the patient's behavior. This shift places greater responsibility on the companion to engage with and influence the patient's adherence to the treatment, highlighting a difference in the level of involvement expected in each scenario.

5. Conclusions and Discussions

Existing research has demonstrated the complex nature of companion participation in medical consultations. The current study explores the nuanced interactional and relational dynamic of TCM consultations that involve doctor, patient and patient's companion(s). By examining cases where doctors involve patients' companions to address patient resistance, I demonstrate that companions often navigate two distinct sets of concerns: relational and medical. This raises an important question regarding what constitutes a good companion —should they support the doctor's agenda to mitigate patient resistance, or should they side with the patients and reinforce their resistance. Most companions in my study chose to side with the patients, leading the doctors to abandon their efforts to propose lifestyle changes (28 out of 39 cases). Notably, in the 11 successful cases, the patients' resistance was more tacit and "weak". It can be argued that when patients do not exhibit strong resistance to the doctors' recommendations, there is more "leeway" for companions to negotiate and potentially persuade the patients to comply.

Findings from this study contribute to several areas in EMCA research, particularly medical conversation analysis. First, research on TCM interactions remains limited, likely due to its relatively "opaque" nature. Although this study is only a small step, it advances our understanding of the interactional construction of TCM encounters. Second, my analysis contributes to research on patient resistance and the strategies doctors use to address it. By involving companions, doctors adopt an alternative approach to overcoming patient resistance. While not always successful, this practice can help doctors advance their medical agenda in certain cases, especially when patients do not strongly object to the doctors' recommendations. My analysis offers insight into the potential roles that companions play in medical interactions. Past research has suggested that companions can either facilitate or obstruct the medical agenda, while current study broadens the perspective by introducing the relational dimension of companion participation. Companions who refuse to assist the doctors may be viewed as "obstructive" from a medical standpoint, yet their alliance with the patients can be seen as "supportive" from the patients' perspective. This discovery has practical implications, providing medical practitioners with deeper insights into the nuanced nature of the patient-companion-provider dynamic.

References

Adelman, R. D., Greene, M. G., & Charon, R. (1987). The Physician-Elderly Patient-Companion Triad in the Medical Encounter: The Development of a Conceptual Framework and Research Agenda. The Gerontologist, 27(6), 729-734. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/27.6.729

Antaki, C., & Chinn, D. (2019). Companions' dilemma of intervention when they mediate between patients with intellectual disabilities and health staff. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(11), 2024-2030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.05.020

Bolden, G. B. (2000). Toward Understanding Practices of Medical Interpreting: Interpreters' Involvement in History Taking. Discourse Studies, 2(4), 387-419. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445600002004001

Chinn, D. (2022). 'I Have to Explain to him': How Companions Broker Mutual Understanding Between Patients with Intellectual Disabilities and Health Care Practitioners in Primary Care. Qualitative Health Research, 32(8-9), 1215-1229. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323221089875

Clayman, M. L., Roter, D., Wissow, L. S., & Bandeen-Roche, K. (2005). Autonomy-related behaviors of patient companions and their effect on decision-making activity in geriatric primary care visits. Social Science & Medicine, 60(7), 1583-1591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.004

Clemente, I. (2009). Progressivity and participation: Children's management of parental assistance in paediatric chronic pain encounters. Sociology of Health & Illness, 31(6), 872-888. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01156.x

DiMatteo, M. R. (2004). Social Support and Patient Adherence to Medical Treatment: A Meta-Analysis. Health Psychology, 23(2), 207-218. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207

Ellingson, L. L. (2002). The roles of companions in geriatric patient-interdisciplinary oncology team interactions. Journal of Aging Studies, 16(4), 361-382. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0890-4065(02)00071-3

Fioramonte, A., & Vásquez, C. (2019). Multi-party talk in the medical encounter: Socio-pragmatic functions of family members' contributions in the treatment advice phase. Journal of Pragmatics, 139, 132-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2018.11.001

Hepburn, A. (2017). Transcribing for social research. SAGE Publications.

Heritage, J. (1985). A change-of-state token and aspects of its sequential placement. In J. M. Atkinson (Ed.), Structures of Social Action (1st ed., pp. 299-345). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511665868.020

Heritage, J., & Robinson, J. D. (2006). The structure of patients' presenting concerns: physicians' opening questions. Health communication, 19(2), 89-102. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc1902_1

Hoey, E. M. (2014). Sighing in Interaction: Somatic, Semiotic, and Social. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 47(2), 175-200. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2014.900229

Hsieh, E. (2007). Interpreters as co-diagnosticians: Overlapping roles and services between providers and interpreters. Social Science & Medicine, 64(4), 924-937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.015

Ishikawa, H., Roter, D. L., Yamazaki, Y., & Takayama, T. (2005). Physician-elderly patient-companion communication and roles of companions in Japanese geriatric encounters. Social Science & Medicine, 60(10), 2307-2320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.071

Laidsaar-Powell, R. C., Butow, P. N., Bu, S., Charles, C., Gafni, A., Lam, W. W. T., Jansen, J., McCaffery, K. J., Shepherd, H. L., Tattersall, M. H. N., & Juraskova, I. (2013). Physician-patient-companion communication and decision-making: A systematic review of triadic medical consultations. Patient Education and Counseling, 91(1), 3-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.007

Mikesell, L. (2009). Conversational Practices of a Frontotemporal Dementia Patient and His Interlocutors. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 42(2), 135-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810902864552

Pino, M., Doehring, A., & Parry, R. (2021). Practitioners' Dilemmas and Strategies in Decision-Making Conversations Where Patients and Companions Take Divergent Positions on a Healthcare Measure: An Observational Study Using Conversation Analysis. Health Communication, 36(14), 2010-2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1813952

Pino, M., & Land, V. (2022). How companions speak on patients' behalf without undermining their autonomy: Findings from a conversation analytic study of palliative care consultations. Sociology of Health & Illness, 44(2), 395-415. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13427

Pino, M., Land, V., & Hoey, E. (2024). Moving Towards (and Away From) Possible Discussions About Dying: Emergent Outcomes of Companions' Actions in Hospice Consultations. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v7i3.144611

Pomerantz, A. (1986). Extreme case formulations: A way of legitimizing claims. Human Studies, 9(2-3), 219-229. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00148128

Robinson, J. D. (1998). Getting down to business: Talk, gaze, and body orientation during openings of doctor-patient consultations. Human Communication Research, 25(1), 97-123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1998.tb00438.x

Robinson, J. D. (2003). An interactional structure of medical activities during acute visits and its implications for patients' participation. Health Communication, 15(1), 27-59. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327027HC1501_2

Robinson, J. D. (2013). Epistemics, action formation, and other-initiation of repair: The case of partial questioning repeats. In M. Hayashi, G. Raymond, & J. Sidnell (Eds.), Conversational Repair and Human Understanding (pp. 261-292). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511757464.009

Robinson, J. D., & Kevoe-Feldman, H. (2010). Using Full Repeats to Initiate Repair on Others' Questions. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 43(3), 232-259. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2010.497990

Sidnell, J., & Stivers, T. (Eds.). (2012). The Handbook of Conversation Analysis (1st ed.). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118325001

Solomon, O., Heritage, J., Yin, L., Maynard, D. W., & Bauman, M. L. (2016). 'What Brings Him Here Today?': Medical Problem Presentation Involving Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Typically Developing Children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(2), 378-393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2550-2

Stivers, A. (2004). "No no no" and Other Types of Multiple Sayings in Social Interaction. Human Communication Research, 30(2), 260-293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2004.tb00733.x

Stivers, T. (2002). Presenting the Problem in Pediatric Encounters: "Symptoms Only" Versus "Candidate Diagnosis" Presentations. Health Communication, 14(3), 299-338. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327027HC1403_2

Stivers, T. (2005). Parent Resistance to Physicians' Treatment Recommendations: One Resource for Initiating a Negotiation of the Treatment Decision. Health Communication, 18(1), 41-74. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc1801_3

Stivers, T. (2007). Prescribing under pressure: Parent-physician conversations and antibiotics. Oxford University Press.

Stommel, W. J. P., & Stommel, M. W. J. (2021). Participation of Companions in Video-Mediated Medical Consultations: A Microanalysis. In J. Meredith, D. Giles, & W. Stommel (Eds.), Analysing Digital Interaction (pp. 177-203). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64922-7_9

Tsai, M. (2015). Where do they stand? Spatial arrangement of patient companions in geriatric out-patient interaction in Taiwan. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Professional Practice, 239-260. https://doi.org/10.1558/japl.v4i2.239

Vick, J. B., Amjad, H., Smith, K. C., Boyd, C. M., Gitlin, L. N., Roth, D. L., Roter, D. L., & Wolff, J. L. (2018). "Let him speak:" a descriptive qualitative study of the roles and behaviors of family companions in primary care visits among older adults with cognitive impairment. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4732

Wei, W. (2021). Medical interaction in traditional Chinese medicine. https://doi.org/10.7282/T3-M9G3-EA30

Wei, W. (2024). Beyond the patient-doctor dyad: Examining "other" patient engagement in Traditional Chinese Medicine consultations. Social Science & Medicine, 340, 116390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116390

Werner, P., Gafni, A., & Kitai, E. (2004). Examining physician-patient-caregiver encounters: The case of Alzheimer's disease patients and family physicians in Israel. Aging & Mental Health, 8(6), 498-504. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860412331303793

Wolff, J. L., & Roter, D. L. (2012). Older Adults' Mental Health Function and Patient-Centered Care: Does the Presence of a Family Companion Help or Hinder Communication? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(6), 661-668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1957-5

Yan, T., & Yang, M. (2024). Adult Children as Companions in Geriatric Consultations: An Interpersonal Perspective from China. Health Communication, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2024.2364442

杨子, 王雪明, & 伍娜. (2018). 第三方陪同就诊的会话特征分析. 语言教学与研究, (1), 101-112.

1 Damp-heat constitution (DHC) implies superabundant dampness and heat. Excessive heat results in yellow and smelly urine, while excessive damp-heat causes people to have red eyes or eye excrement, sticky stools (Zhao et al., 2023)↩