Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Material Constraints for Assistant-Supported Learning:

The Case of a Visually Impaired Student in

Classroom Interaction

Thomas L.W. Toft & Brian L. Due

University of Copenhagen

Abstract

This paper explores classroom desk interaction where the student has a visual impairment (VIS), and the interaction involves a third supportive party, the student's learning support assistant. Based on video recordings and multimodal conversation analysis, the paper examines how a VIS, his assistant, and the teacher within a contingent socio-material environment work toward solving an assignment. The analysis is organized following the sequential unfolding of the assignment-solving situation, going from a) determining the need for teacher assistance, b) the recruitment of the teacher's assistance with the assignment, c) how the participation framework for the joint activity of reviewing the assignment is established with the assistant positioning herself as a fellow "learner", and d) how the issue is identified and solved. The analysis shows the situated properties of the socio-material environment in which the participants and the local material contingencies are assembled and thus become consequential for the collaborative and observable production of the situation.

Keywords: visually impaired student, learning support assistant, desk engagement, participation framework

1. Introduction

A perspicuous setting for studying the role of companions in social interaction is among visually impaired persons, who typically experience difficulties in accomplishing everyday life activities, such as shopping for groceries at the supermarket, without some form of assistance (Jones et al., 2019). Many rely on nonhuman assistance in the form of assistance guide dogs (Due, 2023b; Due & Lange, 2018; Mondémé, 2020) and assistive technology (Lüchow et al., 2023; Reyes-Cruz et al., 2022) besides human assistance when, for instance participating in sports activities (Simone & Galatolo, 2020) or navigating through spatial surroundings (Relieu, 2024; Vincenzi et al., 2021). In this paper, we contribute with new knowledge about the role of companions in institutional interaction by focusing on Visually Impairment Students (VISs) who are participating in regular classes in schools where they are provided with the necessary support to ensure their participation in the learning environment, most frequently in the form of a personal learning support assistant (Blatchford et al., 2012; Giangreco et al., 2014; Moriña, 2017). While these students, in most cases, can participate independently with the help of assistive technology, for example, electronic braille note-takers and screen readers, they often experience challenges in mathematics and science classes that require additional support. In this paper, we report from video ethnographic fieldwork in Danish schools, specifically focusing on how VISs interact during these classes while their assistant supports them. Research has shown that, in general, VISs underperforms in mathematics and science classes and that the challenges mainly concern the graphics (e.g., diagrams and graphs) and similar representations of visual information that are an integral part of the learning material and may be inaccessible to visually impaired people, even when using assistive technology (Brothers, 1973; Clamp, 1997; Morash & Mckerracher, 2014; Rapp & Rapp, 1992; Rosenblum et al., 2019; Smith & Smothers, 2012). Consequently, to ensure these students' ability to work on classroom assignments featuring graphical representations of information, they are often supported by a sighted companion, that is, a learning support assistant, who is responsible for providing visual descriptions of the graphics, thereby enabling the students to possibly comprehend and engage with the learning material (Butler et al., 2017).

When VISs perform individual work on classroom assignments with the aid of their assistant, they may - similar to their sighted peers - encounter assignment-related difficulties that require assistance from the teacher, which leads to engagement in the form of a "desk interaction" (Tanner, 2014). In this paper, we show that since the VIS and the teacher cannot establish joint visual attention toward the graphics that constitute the assignment and are central to the joint activity of reviewing the student's work, the students must rely on the assistant to act as an intermediary in conversation with the teacher. While the assistant must assist in such situations, no predefined procedures exist. Furthermore, learning support assistants are often fellow students or teachers who have not received formal training in supporting VISs (Caldwell & Teagarden, 2006; Giangreco et al., 2014; Herold & Dandolo, 2009); instead, they have developed their own individual practices for assisting in the classroom (Bosanquet & Radford, 2019).

Prior studies examining assistants' practices of assisting impaired students have found that assistants may orient toward task-solving rather than learning through processes (Bosanquet & Radford, 2019; Radford et al., 2011). The research reported in this paper confirms that finding. However, we will also demonstrate, that this practice by the assistant is not a verbal strategy among other possible, but rather a direct consequence of the situated socio-material assemblage (Due, 2023d), consisting of heterogenous elements such as a blackboard, computer screen, table, other students, the teacher, and the spatial configuration of the classroom. Our research question is thus: How do a VIS, an assistant, and a teacher within a contingent socio-material environment work toward solving an assignment? We will show how the assistant comes to enact the role of being a "learner" in interaction with the teacher while temporarily sidelining the VIS and that this organization is orchestrated by specific socio-material circumstances.

Drawing on our video data of VISs (aged 18-22) in Danish classrooms, we show the extended sequential unfolding of a single case. It is not a unique case but a common situation described in previous studies on classroom interactions involving sighted students with special needs (e.g., Stribling & Rae, 2010). Based on this single case analysis, this paper contributes to studies within EMCA on a) classroom interaction, b) disability studies, and c) studies of companionship by shifting the analytical focus from conversational patterns, action formation, and individual resources toward how persons and materials assemble within the unfolding of the learning activity. We argue that it is not just the VIS, the assistant, or the teacher alone and their coordinated interactions that secure the progressivity in this encounter, but instead that the material environment presents particular possibilities and constraints that structure the unfolding interaction. The agency employed in achieving a learning sequence is thus shown to be distributed among the local heterogeneous elements. Hence, this paper also contributes methodologically to EMCA by d) expanding the understanding of agency as a prime human phenomenon to being a distributed achievement (Due, 2021; Enfield & Kockelman, 2017).

2. EMCA Research on Assisting Impaired Persons

EMCA researchers have examined a range of institutional interactions involving participants with conditions such as dementia or autism, who are aided by a companion that provides communicative support. These interactions include doctor-patient consultations (Antaki & Chinn, 2019; Chinn, 2022; Chinn & Rudall, 2021) and social care assessment meetings (Nilsson & Olaison, 2022; Österholm & Samuelsson, 2015; Samuelsson et al., 2015). Indeed, a small but consistent line of research within EMCA has provided insights into assistants' practices for supporting visually impaired persons (VIPs) during goal-oriented activities such as navigating the city (Vincenzi et al., 2021), climbing (Simone & Galatolo, 2020, 2021, 2023), and learning mathematics (Due, 2024b).

Vincenzi et al. (2021) demonstrate that sighted companions orient to obstacles while walking with VIPs by adjusting the progression of their talk and their bodily conduct, thereby making the VIPs aware of spatial features that necessitate a coordinated change in the participants' joint movement. Rather than verbalizing that they are approaching a narrow gap, it is shown that the companion may slow down the walking pace and move her guiding arm, prompting the VIP to alter the position of his moving body (p. 11). Thereby, the participants collaboratively establish "common spaces" that enable them to successfully traverse the spatial environment despite not having equal sensory access to the surroundings (Vincenzi et al., 2021). This kind of collaborative work involved in companion-VIP navigation is also examined in Simone and Galatolo's (2020; 2021) studies on indoor paraclimbing that show that climbing trainers have developed a routine practice of supporting VIPs by making visual features of the artificial climbing wall, that is, the colored hand and foot holds, accessible through verbal instructions, thereby enacting the role of being the VIPs' eyes (p. 287). This not only involves orientation to the position of the VIP's arms and legs in relation to the holds but also to the tactile and haptic features of the wall that are available to the VIP as he explores the wall. Thus, the supportive actions of the trainer are demonstrably aimed towards providing the VIP with information that he may interpret and utilize in conjunction with his own sensory experience of the wall to make sense of the route layout, thereby allowing him to perform as a competent climber, that is, to successfully plan and execute the complex body movements that are necessary to ascend the color marked route (Simone & Galatolo, 2020).

Besides navigation, sighted companions may assist VIPs in experiencing (through touch) physical features and objects within the material environment that are relevant for accomplishing an ongoing activity. In another study on climbing trainer-VIP interaction, Simone and Galatolo's (2023) demonstrate how trainers may initiate the tactile mapping of foot holds at the bottom of the wall by uttering "and you have" which the VIP treat as an invitation to move their body toward a specific material object in coordination with the trainer, resulting in both of them positioning themselves in front of a designated hold, enabling the trainer to guide the VIP's hand towards it. Through this practice, the trainer is shown to be able to support the VIP in achieving a tactile experience of the position of different holds that are to be used to begin the ascend (Simone & Galatolo, 2023). In a classroom context, Due (2024b) explores a teaching assistant's practice of assisting a VIS in learning mathematical geometrics by using a ruler shaped like a triangle as a touchable representation of the Pythagorean theorem. By examining how the assistant applies "guided touch", that is, places the VIS' hand on different parts of the triangle, Due (2024b) demonstrates that it fails to provide the VIS with an understanding of the mathematical concept as it does not enable a haptic experience of the triangle, that is necessary to comprehend the spatial relation between the corners. It is thereby shown how supporting a VIS in understanding the shape and dimensions of objects by applying guided touch should involve individual active touch, whereby the VIS may explore the object. In general, these studies (and others (Due et al., 2024; Due & Lüchow, 2023; Hirvonen, 2024)) show the intricate co-operative actions between the VIP and the companion assistant applied to solve beforehand tasks.

EMCA studies on student-assistant interaction in educational settings have explored classroom activities involving students with some form of disability or developmental disorder affecting their educational progression, though not specifically visual impairment (except Due 2024). Typically, the focus is on some form of language problems and communicative impairment subsumed under the rubric of atypical interaction (Wilkinson et al., 2020). A fundamental interest has been to explore how assistants orient to the students' distinct participation barriers, such as difficulty with maintaining attention or following instructions, and enact their role in the classroom through pedagogical scaffolding actions, meaning "responsive actions that take the competence the student demonstrates into account" (Koole & Elbers, 2014, p. 58). These actions can assist the student in accomplishing a difficult task more or less on their own and thus achieve learning with as little support as possible (Stribling & Rae, 2010). In Tegler et al.'s (2020) study on students who communicate through eye-gaze-accessed speech-generating devices, scaffolding actions involve the assistant commenting on the student's on-screen activities, that is, the movements of the eye-gaze cursor, thereby prolonging the student's response time as he attempts to answer the teacher's question (p. 208). In Stribling and Rae (2010) it is shown that assistance to a student with severe learning disabilities, among other things, guides the student's attention towards learning materials that are relevant for the current activity, for example, wooden blocks used for practicing counting, thus encouraging the student to participate. However, studies have also demonstrated an absence of scaffolding. By comparing the pedagogical actions of teachers and assistants during mathematical classes, including students with an autism spectrum disorder, Radford et al. (2011) found that assistants were more oriented towards students' on-task behavior and completion of textbook assignments than their ability to comprehend the involved underlying mathematical concepts and methods of reasoning. Thus, when displaying difficulties with assignments, assistants are shown to provide answers and corrections rather than utilizing scaffolding practices that could serve to elicit self-corrections from the student (Bosanquet & Radford, 2019; Radford et al., 2011). Through this practice, Radford et al. (2011) argue that assistants appear to prioritize the students' experience of success, that is, correctly solving assignments at the same pace as their peers, at the expense of their individual learning.

In our data, we generally find the same kind of interactional pattern as shown by Radford et al. (2011) and Bosanquet & Radford (2019) (i.e., that assistants appear to prioritize the students' experience of success with solving the assignment at the expense of the development of their mathematical thinking), and this will become apparent in the analysis. We thus contribute to this line of research within the atypical program (Antaki & Wilkinson, 2013) with a confirmation of the assistant-supported dynamics that seem to be produced across impairment types. However, contrary to the typical focus within this atypical program, our argument will not primarily be based on the conversational structure but instead on the socio-material circumstances.

3. Setting, Method and Analytical Focus

This paper is based on data from video-recorded classroom interactions in which VISs participates together with sighted students. The study is part of a larger project on Danish visually impaired people's usage of electronic braille note-takers in everyday activities (Sandersen et al., 2022). The five participants in the project were 18-22 years of age. The project included ethnographic observations and fieldwork following the students in school and interviewing them before and after a day in school. This ethnographic knowledge serves as the backbone for understanding the students' everyday practices. For this paper, however, we only use the video recordings for analysis. As part of the project, one of the VISs, David, was observed and filmed throughout the course of a whole school day as he attended different lessons, resulting in approximately six hours of video data. While David mostly participated in classroom activities independently through assistive technology, he was accompanied by appointed learning support assistants throughout a mathematics, chemistry, and physics class, as these involved graphic-based learning objects. In line with the general practice in classrooms, David's assistants were teachers affiliated with his school who had not received formal training in supporting VISs.

For this paper's purpose of studying assistant-supported interaction, we use data from a two-hour chemistry class attended by David, during which the teacher is recruited (Kendrick & Drew, 2016) to help with a classroom assignment that David has been working on in collaboration with his assistant. The analysis is based on two recruitment instances from a chemistry class, with one chosen as a single case for this paper. The presented data was recorded with multiple HD cameras: Two cameras recorded David and his assistant at their desk from different angles (Fig. 1-2). A third camera recorded the screen of the assistant's laptop as she supported David (Fig. 3). To capture David's actions on his electronic braille note-taker, an external computer was connected to the device and placed on the floor below the desk. This screen was recorded with a fourth camera (Fig. 4). As the recordings were later synchronized, this specific camera set-up enabled us to track the collaboration between David and his assistant and to capture the interaction from a global frame. Two researchers were also present during the recorded classes, taking field notes and occasionally checking the equipment. We take it for granted that the equipment and the researchers' presence are part of the phenomenal field (Barad, 2007), but we have no evidence of these directly affecting the unfolding of the sequences we analyze in this paper.

We have applied an ethnomethodological conversation analytical (EMCA) methodology to approach the data, and we built especially on the research that has highlighted the role of the material environment in accomplishing activities (e.g., Goodwin, 2000a, 2007; Luff et al., 2000). We do, however, also aim to expand the understanding of materials for the accomplishment of situations. The typical understanding of materials in EMCA relates to objects as interacted with (Nevile et al., 2014) and in and through these practices objects/materials are only considered relevant for the interaction through direct and accountable orientations. Taking inspiration from the work that connects EMCA with assemblage theory and sociomateriality - Due (2023d, 2023a), Raudaskoski (2021, 2023) and Caronia (2018; Caronia & Cooren, 2014) - we aim also to expand the analytical framework in two ways: a) from single human agency to agency as distributed within assemblages and b) from only recognizing the relevancy of materials when oriented to, to including materials in the environment when it can be witnessed to be consequential for the unfolding of the activity. An approach that has also been suggested to be called post-praxiology (Due, 2024a; forth.). This expansion of the methodological framework away from that which can only be analyzed following the "next turn proof procedure" (Sacks et al., 1974) is done to include more of that which is observably producing the situation and the emerging activity.

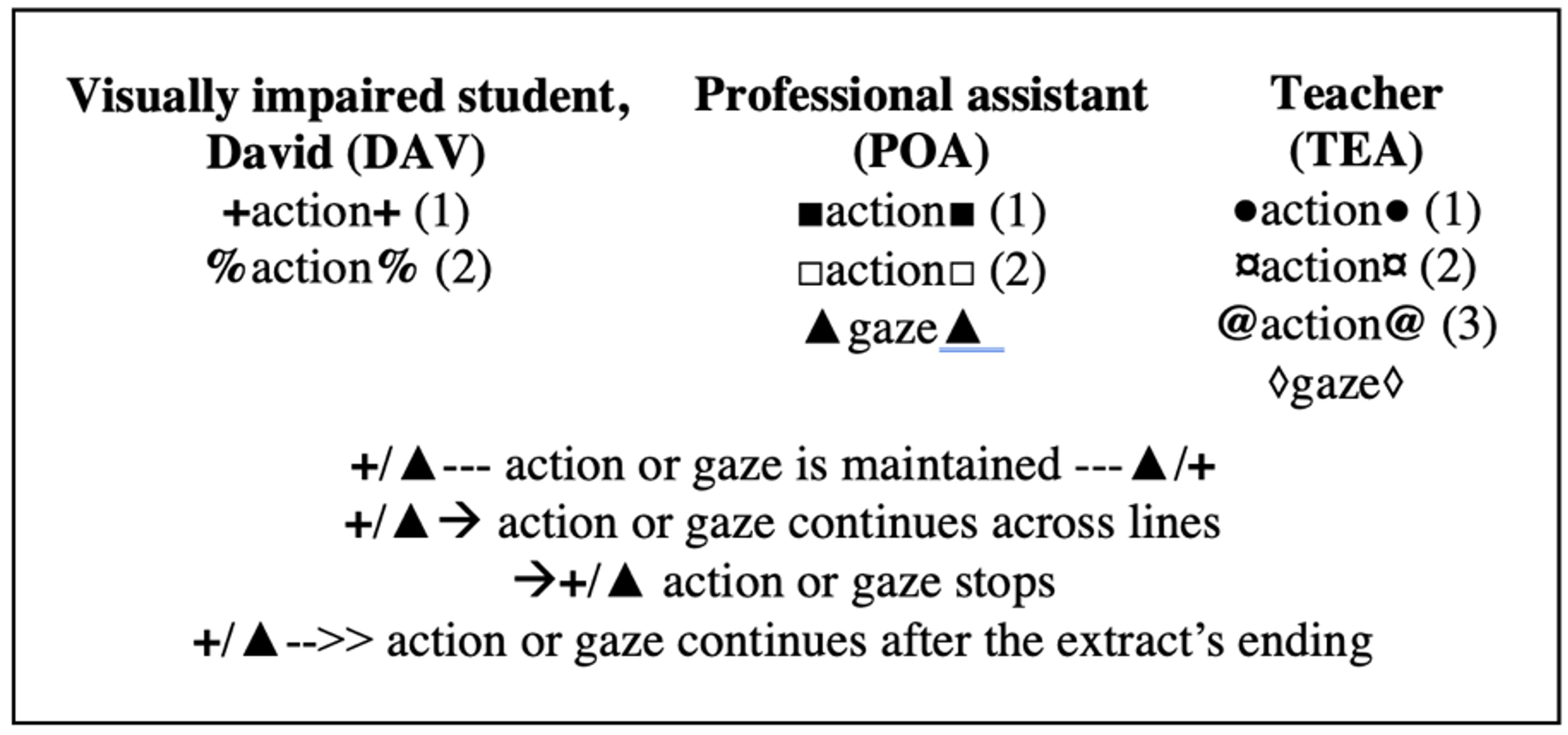

The video has been transcribed using the Jeffersonian (2004) system and Mondada's (2016) conventions for multimodal transcriptions. The transcription symbols are described in Appendix (Table 1). Data fragments have been anonymized in accordance with the University of Copenhagen's rules on personal data management (University of Copenhagen, 2022), and every participant has signed a confidentiality agreement. The participants' names are pseudonyms.

The analysis is organized following the sequential unfolding of the situation, going from a) determining the need for teacher assistance, b) the recruitment of the teacher's assistance with the assignment, c) how the participation framework for the joint activity of reviewing the assignment is established with the assistant positioning herself as a fellow "learner", and d) how the issue is identified and solved. The analysis will show how the socio-material organization structures the learning environment in such a way so that the assistant enacts the category of being a "learner" or a "student," both of which demonstrably differ from her institutionally situated identity as David's "assistant."

Fig. 1-2. David and his learning support assistant sitting side by side.

Fig. 3-4. The assistant's laptop screen and David's actions on his braille note-taker device.

4. Analysis

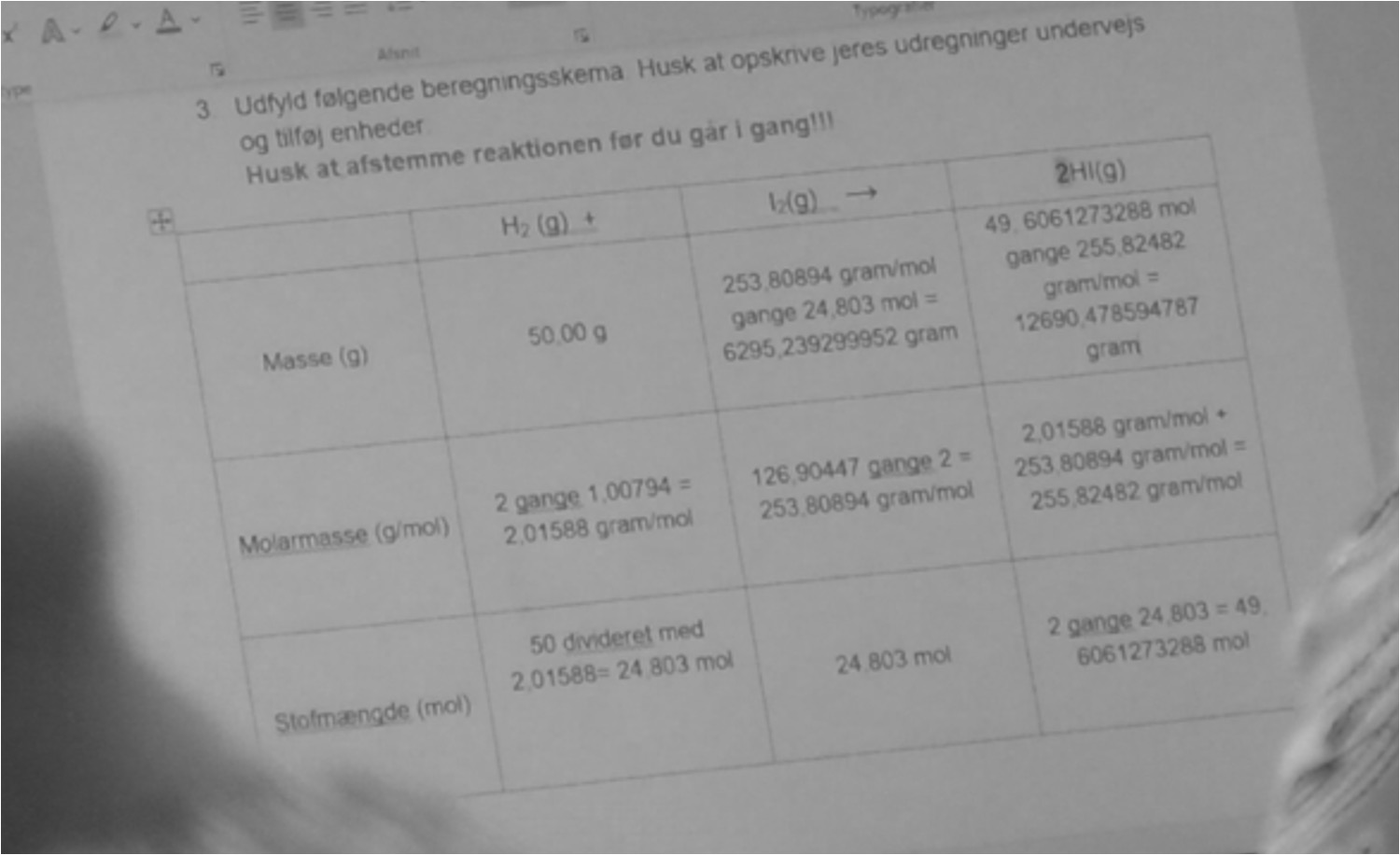

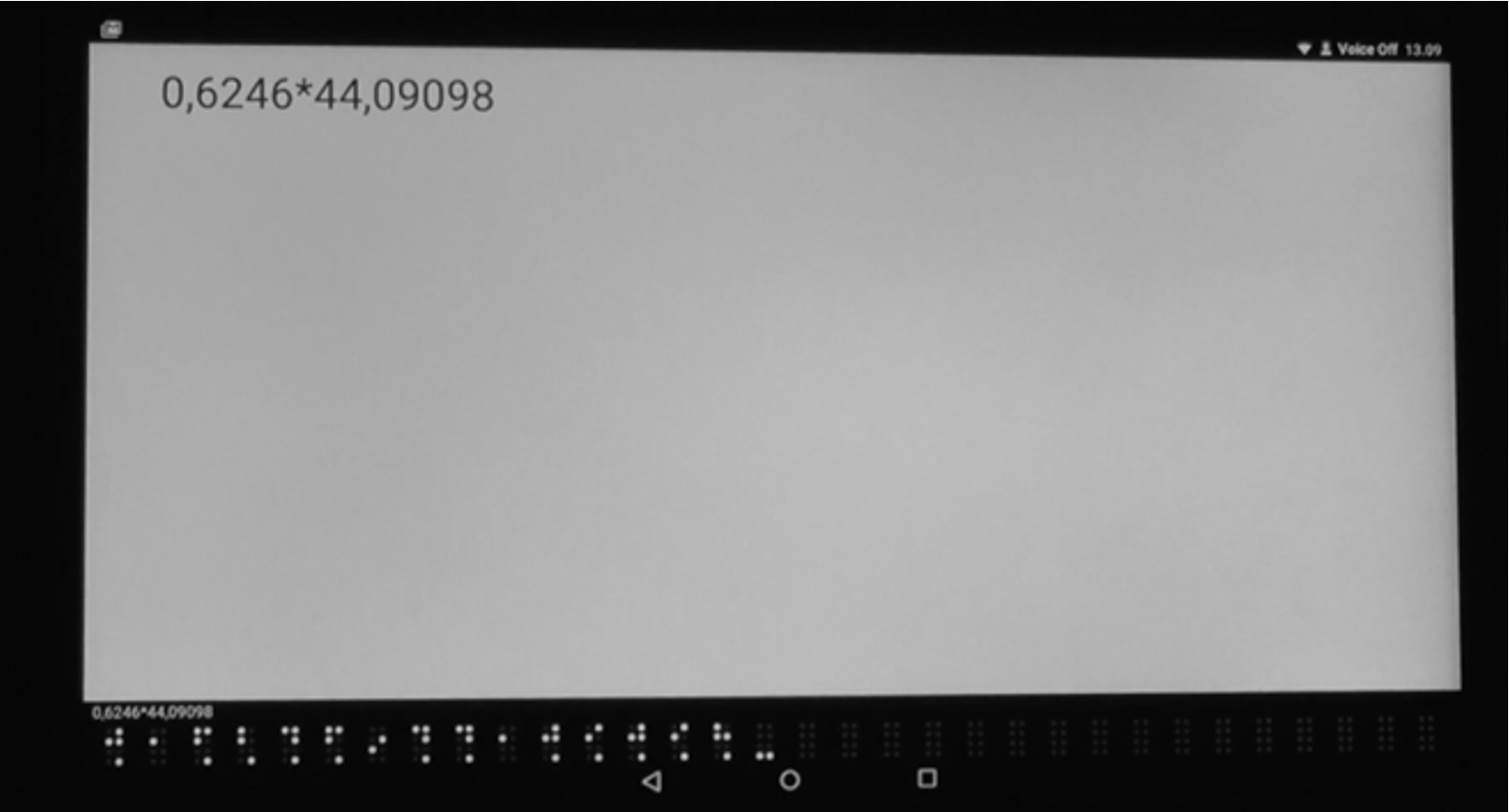

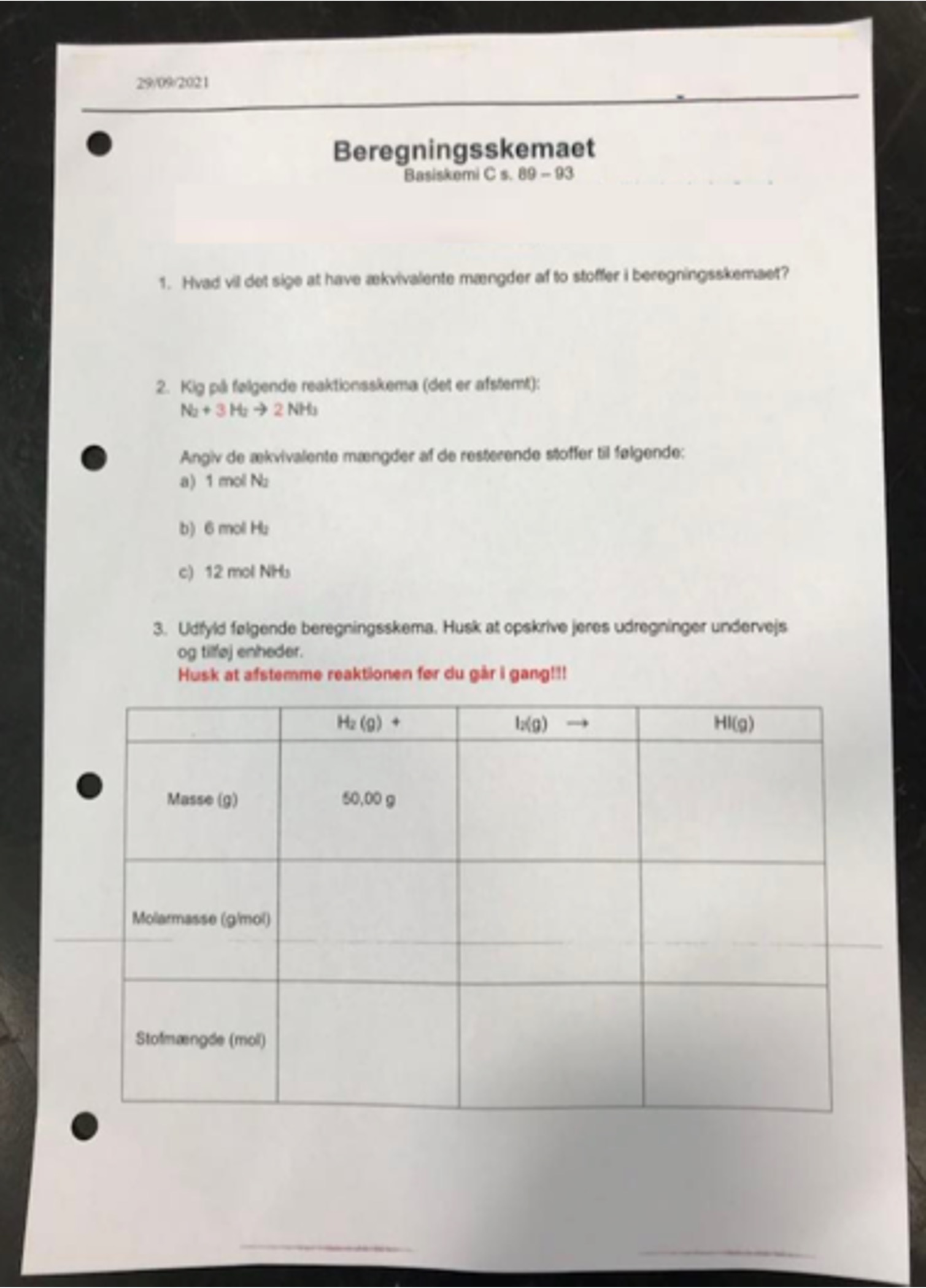

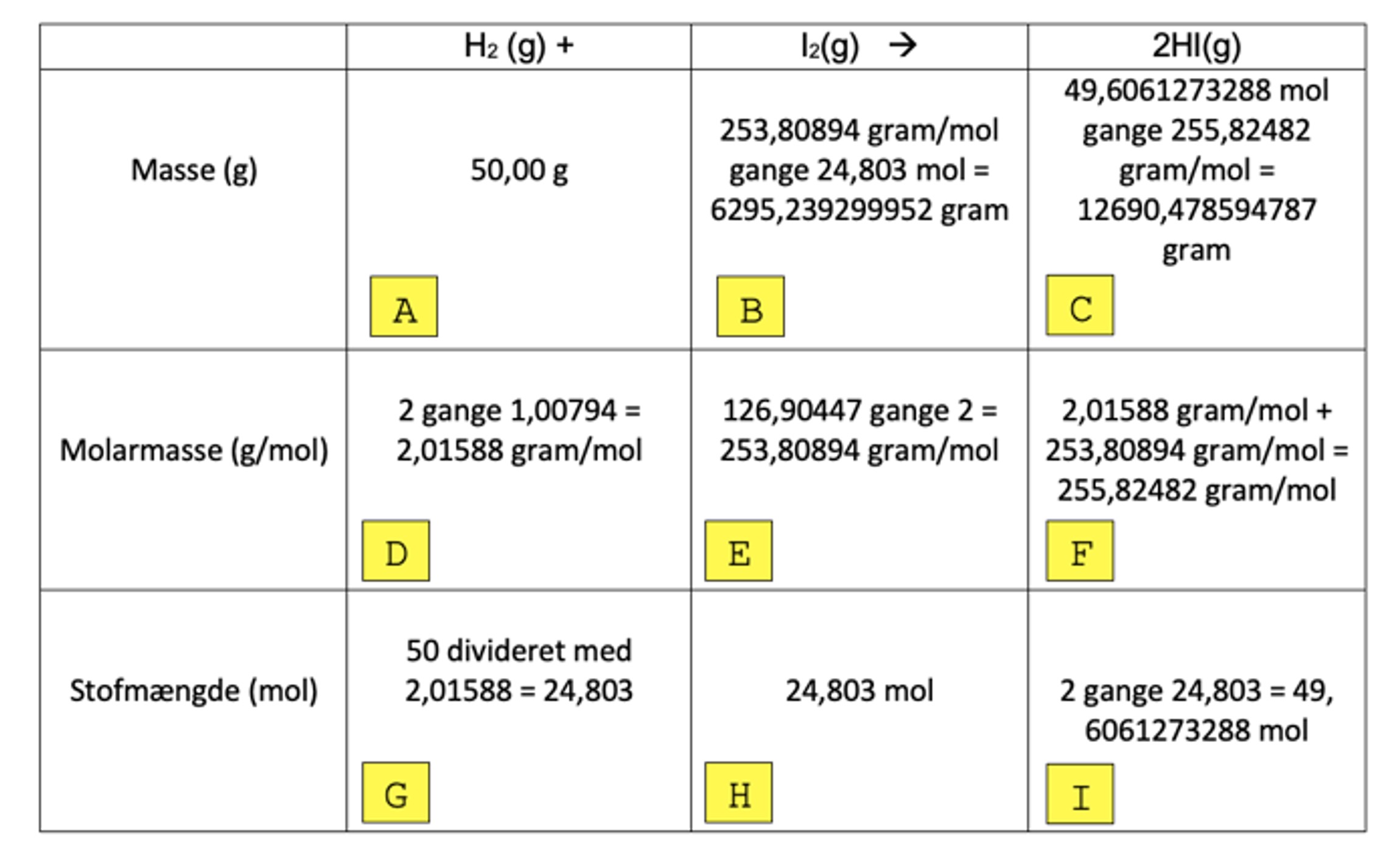

In the following, we examine an instance from the chemistry class where the students were given a paper worksheet featuring a table containing cells with different values to be calculated in a specific order (see Appendix, Table 2). As David has difficulties reading and writing in tables with his electronic braille note-taker, he is assisted by his learning support assistant, who has received a Word document including the table, which she accesses via her laptop in the classroom (Fig. 3). In this way, the assistant can verbally guide David as he works on the assignment and provides him with the numbers that he is to multiply and add using his note-taker (Fig. 4). Thus, solving the assignment involves co-operative work (Goodwin, 2017) between the participants, with the assistant providing visual descriptions of the on-screen table and typing in David's calculations.

4.1. Establishing the need for teacher assistance (Excerpt 1)

The extract below unfolds a couple of minutes after David (DAV) and the learning support assistant (LSA) have completed the table that constitutes the assignment. The assistant introduced the assignment and the necessary calculations, and David did the calculations on his note-taker. At the beginning of the excerpt, the assistant examines the calculated values as they appear in the grid layout on her laptop and voices concern to David regarding their correctness. There are three overall points we want to show with this excerpt: 1) how it is the assistant (and not David (VIS)) that verbalizes concern with the completed assignment, 2) how the learning materials provide her with a visual overview which enables that concern and the material layout of the setting structures the kinds of actions that gets produced, and 3) how the assistant initiates the need for teacher assistance.

Extract 1.

Open in a separate window

In line 1, the assistant directs attention towards the current state of her and David's work by providing a negative assessment designed with the evaluative term "not right" that attends to the correctness of the table content, which is verbally referred to using the deictic term "it" (Sidnell & Enfield, 2017). When examining this "objective evaluation" (Wiggins & Potter, 2003), we note that the assistant orients to her perception of the content as it "looks" on her laptop and thereby shares her "sighted experience" (Vom Lehn, 2010) of the completed assignment with David. The assistant's concern is thus demonstrably presented as pertaining to the visual appearance of the entire table (Fig. 5.2).

As the assistant continues by delivering a proposal ("but that we can maybe find out" l. 1), she orients to David's participation by treating the perceived incorrectness as a matter that requires joint exploration of the table content (the inclusive "we"). However, rather than pursuing the joint exploration of the content to determine the correctness collaboratively, the assistant upgrades her initial claim regarding the state of the assignment by producing a question ("what the hell is wrong here" l. 2), verbally orienting to the results as being (rather than just visually appearing) incorrect and displaying inability to determine the cause.

When examining David's verbal response (l. 3), we note that he orients to his and the assistant's different access to the object of evaluation as he produces the interrogatively formatted question concerning the assistant's visual perception of the table content as initially verbalized ("does it not look right"). The assistant treats David's question as a request for information regarding the appearance of the content. She then specifies the specific features that prompted the negative evaluation (l. 5). She specifically provides David with the values featured in cells A and B, which we note are interrelated through their arrangement within the table layout, that is, the top row (Fig. 7.2). Following David's minimal response (l. 9), the assistant continues by explicating how these values do not correlate with the value featured in cell C (l. 10-12), thereby seeking to establish a shared understanding of these graphically interrelated values causing the finished table to appear incorrect.

So far, we have observed that the placement and arrangement of the calculated values within the table structure perception, how they are being seen by the assistant and that determining the correctness of the completed assignment demonstrably requires an overview of the content as provided by the laptop (Fig. 5.2). However, when zooming in on the assistant's gaze behavior it is observable that the blackboard also features as a resource for assessing the assignment and that its content, that is, the teacher's written instructions and an example of a completed table (Fig. 6), is utilized in conjunction with the laptop screen. Specifically, we note how the assistant orients to the blackboard content as a point of reference that validates her assessment of the on-screen table (l. 2 and 12) as well as the correctness of her and David's procedural approach to filling it out (l. 21). Thus, as the assistant voices a need of seeking the teacher's assistance with the assignment (l. 23), the decision is demonstrably informed by the complex interrelation of two visual objects within the material environment. However, whereas the assistant and the VIS accountably orient to the computer, the blackboard is a background feature that is only analyzable if we include a methodological openness towards the consequentiality of materials that are not directly accounted for but still observably configured in the phenomenal field.

When examining the assistant's utterance in line 23, it is observable how it is designed to get the teacher to assist her in seeing where the mistake is located. Thus, finding the mistake and making it "correctable" is demonstrably produced as the assistant's visual project. Following the closing of the interaction (not included in the transcript), the assistant continues to shift her gaze between the laptop screen and blackboard in silence before eventually restating that the table is incorrect and that the teacher's assistance is needed, with no response from David, followed by a change in her seated position as she raises her right hand (l. 27-34).

This first excerpt shows that the graphical and visual organization of the learning material has implications for David's ability to determine the correctness of the completed assignment and how the assistant may include him in identifying the trouble source. Even though David has calculated the values that constitute the completed assignment (prior to the extract) and thus is aware of their presence as distinct numbers within the table, the correctness of the assignment is determined by assessing the interrelation between these different values as established through their graphical arrangement in rows and columns. Much like the archaeological practice of using a Munsell chart to determine colors in dirt (Goodwin, 2000b), the "perceptual task" of identifying incorrect features, therefore, involves careful examination of the entire table so as to compare the different calculations and resulting values and discover those that appear problematic. Following the ethnomethodological misreading of Gurwitsch (Garfinkel, 2021; Gurwitsch, 1964), the entire table and the complete visual overview of the assignment and its materials can be glossed as the gestalt contexture, and the singular components as the functional significances. The practical accomplishment of perceiving the whole gestalt contexture is impossible for the VIS, who only has access to a few of its details (functional significance). As also shown by Due (2024b) and Due and Lüchow (2023) this is a recurrent problem of concerted actions between sighted and visually impaired persons.

Because the table structures how the completed assignment is perceived (Goodwin, 2000b, 2018), David's involvement in identifying the problem is contingent on the assistant's ability to see relevant features within the table that may constitute the trouble source and, therefore, should be verbalized to him.

4.2 Recruiting the teacher's assistance (Excerpt 2)

Having been sitting in silence with her hand raised, the assistant initiates a conversation concerning the cafeteria's menu of the day, which David has difficulties accessing on his note-taker (l. 35-56). We have omitted these lines, and the following excerpt thus unfolds a couple of minutes after the previous excerpt, where the need for seeking teacher assistance was established. Thus, at the beginning of excerpt two, the assistant has initiated summoning the teacher's attention and seeks to recruit (Kendrick & Drew, 2016) her through visual cues while engaging in the "off-task" talk (Markee, 2005) with David (concerning the menu).

To secure the readability of the transcribed excerpt, we have only included the audible part of the teacher's co-occurring interaction with another student that the assistant observably orients to. In the following, we want to show: 1) how the assistant's recruitment-oriented actions are shaped by specific socio-material circumstances within the classroom environment and 2) how these circumstances affect how the off-task talk is suspended in favor of the desired encounter with the teacher.

Extract 2.

Open in a separate window

While David produces a story of "the old days" (l. 56) and verbalizes his trouble with accessing the online menu, the assistant has her right arm raised, with the elbow resting on the desk and the index finger extended (l. 56-57), which is recognizable as a typical bodily summoning practice for students in the classroom seeking to solicit the teacher's attention (Gardner, 2015; Greiffenhagen, 2012; Schegloff, 1968; Tanner, 2014). Even though the assistant initiated the ongoing off-task conversation prior to the transcribed excerpt, we note that she, at this point, only produces a minimal response ("no", l. 59) and refrains from pursuing any further elaboration of David's accessibility difficulties, thus treating the troubles-telling as being complete.

When examining the assistant's embodied actions following the 0.6-second moment of silence, we note how her conversational conduct seems to be occasioned by an assemblage of specific visible and audible circumstances within the socio-material environment that makes it relevant to prioritize the summoning activity: The teacher's current spatial location within the classroom layout as well as the progression of her ongoing activity of assisting the other student, which the assistant demonstrably attends to (l. 62, Fig. 12). By being physically present immediately behind their desk and standing at the pathway next to the row of desks, the teacher may be perceived as being in a "favorable space" for recruitment (Jakonen, 2020), as her bodily position and orientation makes David and the assistant appear "next in line" in her classroom rounds (Fig. 12). Furthermore, the teacher's "yes" (l. 61) to the other student may be heard as a closing evaluative statement meaning that the teacher possibly is about to disengage from the activity of assisting that student, making her available for interaction. Thus, as the assistant immediately directs her gaze towards the teacher following the latter's utterance in overlap with David's talk, and lifts her arm further up, she demonstrably presents herself as attending to these circumstances and treating them as preconditions for being noticed in the busy classroom where multiple students compete for the teacher's attention - rather than being fully engaged in the conversation about the cafeteria menu with David - except for a minimal response ("oh okay" (l. 65)). While the design of David's utterance (l. 66-67) makes some form of agreement or disagreement relevant, the assistant delivers an "oh" (l. 69) immediately after having registered the teacher's bodily orientation towards them (l. 68). By delivering the change-of-state token at this very moment the assistant displays awareness of the teacher's attention having been successfully secured, and as she subsequently lowers her raised arm and reaches for the laptop (l. 70) her bodily conduct can be seen as marking a transition to on-task talk concerning the assignment. In other words, the "oh" is hearable and observable as a response to the approaching teacher rather than David's telling.

This second excerpt shows how the assistant during her and David's "waiting time" demonstrates the "interactional competence" (Jakonen, 2020) necessary for securing the teacher's attention. This involves identifying relevant changes within the socio-material environment - that is, the teacher standing up from the student's desk, turning her body towards the pathway, and engaging in walking - all of which make specific actions relevant for the purpose of receiving help, that is, making a raised hand more visible and maintaining that hand in a visible position. However, while the assistant observably relies on her awareness of the teacher's activity to anticipate when the teacher will be in a "favorable space" for recruitment (Jakonen, 2020) and adjust her summoning actions accordingly, the complexity of the classroom environment - consisting of multiple adjoining desks along the pathway with students who also need assistance - has notable implications for the assistant's ability to anticipate the precise moment the ongoing off-task conversation should be suspended in favor of the desired desk encounter with the teacher, and thus when David should be notified of the teacher's attention having been successfully secured.

Even though the assistant's change of state token may serve to notify David that the teacher has been successfully summoned and that the activity of reviewing the assignment is about to be initiated, David does not display any visible change in orientation as he continues his off-task activity of scrolling through documents on the note-taker. Thus, only the assistant seems to have recognized the teacher's presence, and thus, only she demonstrates readiness to engage in the forthcoming reviewing activity.

The recruitment of the teacher is visually organized following the "raised hand" order and thus naturally delegated to the assistant as it would be much more complicated for the VIS to coordinate the minute interactional features of the raised hand and the visual orientation to and from the teacher with this complex socio-material environment.

4.3 Establishing the participation framework and identifying the issue (Excerpt 3)

In this final excerpt, we examine how the participation framework for the joint activity of reviewing the completed assignment is established, as well as the first part of the reviewing activity, where the teacher localizes the mistake within the on-screen table, enabling the assistant to make the necessary corrections. As the excerpt begins, the teacher leans toward the laptop the assistant is making visually available for examining the content. There are three overall points we want to show with this excerpt: 1) how the assistant is positioned as the primary recipient of the teacher's assistance and the person who is active during the desk encounter, 2) how the material layout and the complexity of the graphic representation of the assignment is consequential for the reviewing activity, and 3) how David only is oriented to once the mistake has been corrected.

Extract 3.

Open in a separate window

Following the teacher's arrival at the desk and her verbal response (l. 71, Excerpt 2), the assistant grabs the laptop and initiates a verbal assessment ("to be honest I really think (0.2) so" (l. 73)). She subsequently pauses this assessment while turning the laptop and placing it sideways on the desk, enabling the teacher to see. Having changed the position of the laptop, the assistant restarts ("I actually think we have done it right" l. 74), and visual attention toward the computer screen is thereby demonstrably treated as necessary for judging the validity of the assistant's positive assessment.

The relevance of showing content on the computer screen is observably achieved within the interactional machinery. However, the prerequisites for turning the screen are found in the material environment: the organization of the table and the chairs structures the possibilities of producing the spatial positions of objects and persons. The exact positioning of the teacher is possibly also accommodated by the equipment used for the ethnography: the screen on the floor delimits the spatial positions the teacher can occupy, and the video recorder enables the current angle and view of the scene for the purposes of our analysis. The recording equipment occupies a slot in the spatial layout. It produces a recording perspective that we cannot exclude the teacher is orienting to when she moves into her current position.

We note that the evaluative term "right" attends to David and the assistant's procedural approach to solving the assignment and that the screen provides a complete picture of this approach which is visibly represented as a series of calculations that follow the structural arrangement of the table layout (Fig. 1.2). Furthermore, by designing the assessment with the pronoun "we", the assistant orients to herself and David as a collective category, a kind of situated "relational pair" (Stokoe, 2012) engaged in a "collaborative-learning activity" (Greiffenhagen, 2012) by solving the assignment together. Thereby, the assistant noticeably positions herself in a role identical to David's - a "learner" to whom the teacher has certain institutional obligations, that is, to give guidance - as well as the primary recipient of the teacher's assistance.

As the assistant continues her turn and verbalizes the reason for the summons, she mobilizes verbal and bodily resources to draw the teacher's attention towards the numbers in two specific cells that moments earlier were established as causing the finished table to appear incorrect (excerpt 1). Utilizing a pointing gesture, the assistant first highlights cell A, featuring the value "50 grams" (Fig. 17.2), to which she verbally refers using the deictic term "that there", and subsequently moves her pointing finger towards cell C which contains the result of the calculation, "12690,478594787 grams" (Fig. 18.2). She then provides a verbal negative assessment regarding the relation between the two cells, "just at all not fit" (l. 76).

While it is apparent that the design of this verbal-bodily structuring of what is to be seen and how it is to be seen (Goodwin, 1994) does not take into account David's impaired visual sense, we note that he has been verbally provided with these values and calculations before the recruitment of the teacher (excerpt 1). Through her conduct, the assistant appears to treat David as knowing what specific features of the completed assignment are made salient. However, we should pay special attention to the fact that, in this sequential environment, David displays difficulty hearing and thus contributing to the talk, as he produces an other-initiated repair designed as a request for repetition, "what are you saying" (l. 77) in overlap with the assistant's talk. Thus, David is noticeably unaware that the top row is being highlighted.

When a ratified participant asks a relevant question, a second pair part production is expected and preferred (Pomerantz, 1984; Schegloff, 1984; Stivers & Robinson, 2006). It is noticeable that neither the assistant nor the teacher responds to Davids question (l. 77). There is only a minimal, barely observable orientation to his relevant question (0.4-second pause (l. 78) and hesitation ("eh") (l. 79)) before the teacher continues her engagement with the assistant: "eh let us see" (l. 79). David is thereby demonstrably positioned as a bystander to the initiated reviewing activity. What could have been reconfigured as a triad of the teacher, the assistant, and the VIS reconfigures into a new dyad between the teacher and the assistant. It does not seem reasonable to infer any subjective strategies for doing so. Rather, the complex socio-material assembly of visual, physical, and digital content configured in particular ways of desks, tables, and computers consequently structures the possibilities for efficient help guided towards problem identification and solutions - rather than engaging (no matter what it takes) in the process.

While David continues his off-task activity on the note-taker, we note how the teacher employs a turn design that includes gesture, an indexical word ("it"), and adverbs relating to place ("here", "under", l. 81), and that the pedagogical action of "pointing out" the mistake thereby clearly is structured around the spatial and visual configuration of the assignment, aimed towards enabling the assistant to make the necessary corrections and thus achieve learning.

After ending the desk encounter (not included in the transcript), the teacher leaves the desk to go and help other students. At the same time, the assistant makes the correct calculations and types the resulting values in the table (lines 88-103). The assistant then initiates the resumption of the collaborative work on the assignment (l. 104). At this point, we note that David is browsing Facebook. We have access to this information from the external screen that displays content from his notetaker. The assistant and the teacher do not have access to this information. From David's perspective, the activity he is engaged in during this interaction is not the repair sequence, locating the mistake in the calculations, but searching and reading on Facebook. When asked to engage (l. 104), David then responds with a repair initiating "what" (106), which displays his disengagement with the teacher/assistant interaction. Following David's utterance (l. 106), the assistant informs him that the mistake has been identified (l. 107), which David then acknowledges (l. 109).

This excerpt shows the assistant's interactional project (Levinson, 2013) to secure the correct result of their assignment. The interactional project does not aim to enable David to learn from their mistakes. David is not established as the primary recipient of the teacher's verbal guidance, nor is he oriented to as a participant who may contribute to locating the problem. During desk interaction, the teachers' pedagogical actions usually build on shared visual perception with students (e.g., Greiffenhagen, 2012; Koole, 2010; Tanner, 2014). As the assistant takes on the role of a "student" who has shared responsibility for the results, the teacher is held accountable for performing actions that will make miscalculations noticeable for the assistant (Majlesi, 2018). Thus, as the teacher orients to her institutional responsibility toward the assistant's situated learning, designing her actions based on the visually impaired student's sense-ability does not become relevant.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we have provided an in-depth analysis of an assignment-solving situation where a VIS and his learning support assistant encounter difficulties during their co-operative work in a graphical table and hence recruit the teacher's assistance. Our analysis confirmed findings from other settings involving impaired students, highlighting that the assistant might be more occupied with helping the impaired student reach the correct answers than learning from identifying and solving mistakes (Radford et al., 2011). We thus contribute with this paper to the ongoing building of knowledge about impaired persons' possibilities to learn in school contexts while being supported by assistants. From a learning perspective, this finding is problematic, as learning is related to practices of doing and engaging with identifying and solving problems in situ (Lave & Wenger, 1991). However, the aim of our analysis has not been to show how the assistant and the teacher exclude the student based on some verbal strategies or excluding intentions, but rather to show that the progressivity of the schoolwork within the classroom environment and the socio-material circumstances of the learning material, structures the emerging helping activity. We have shown how the assistant came to enact the role of being a "learner" in interaction with the teacher while temporarily sidelining the VIS and that this organization is orchestrated by the specific socio-material circumstances of blackboards, computers, tables, chairs, papers, and graphical content only visually available. Whereas prior research has focused on the individual roles of the participants in trying to make the assistant-supported interaction work, we have in this paper shown not just the interactional accomplishment of the potential learning situation but also the situated properties of the very socio-material environment in which the participants and the local material contingencies are assembled and thus becomes consequential for the collaborative and observable production of the assignment-solving situation. There is in this studied phenomenal field an observable ocularcentric organization with an "ocularcentric participation framework" (Due, 2023c) that seems to be routinely produced. This is evidenced by the fact that David does not account for being "left out" of the correction sequence but instead seamlessly engages with Facebook content. In that sense, this data involves what Garfinkel called a "natural experiment", where their contingent sociomaterial practices reveal otherwise taken for granted aspects of ocularcentric designed environments (Due, 2024c). This relates in particular to the visual presentation of the learning materials, but as the analysis showede, these are assembled with the rest of the material environment into coherent gestalts that are firstly available to the sighted participants.

The analysis started from the fact that while David participated in the process of filling out the table (prior to our focus in this paper) and is thus aware of the calculated values that constitute the completed assignment, its material manifestation means that the correctness of the result only is perceivable when examining these values' interrelation. Thus, as the graphical structure of the assignment shapes how the values are perceived, the assistant becomes responsible for securing the correctness. Even though the assistant seeks to include David by verbalizing the problematic features that appear on her screen, the complexity of this dense perceptual field on her screen restricts her from involving him in the process of discovering the cause of the mistake. Furthermore, as the necessity of seeking assistance builds upon the interplay of information provided by the screen and blackboard, David is not in a position to decide to seek assistance.

As the assistant seeks to recruit the teacher, the complexity of the classroom environment - consisting of multiple adjoining desks along the pathway with students who also are in need of assistance - has notable implications for the assistant's ability to anticipate the precise moment the ongoing off-task conversation should be suspended in favor of the desired desk encounter, and thus when David should be prepared to engage in interaction with the teacher. This has notable implications for the subsequent reviewing activity as David becomes a bystander while the assistant is positioned as the primary recipient of the teacher's "corrective feedback," whereby the mistake is made "noticeable and correctable" (Majlesi, 2018).

In sum, this paper has shown how the production of a learning environment in classes where a visually impaired student is supported by an official companion (the assistant) relies not only on the interactional organization and embodied conduct but on the detailed organization in the material environment. Some materials are directly oriented to and made accountable, like the computer screen, which displays the tables, whereas other materials structure the actual accomplishment of the current activities. Surely, the VIS cannot see the content on the computer screen, and thus much perceptual work relies on the work-site details (Garfinkel, 2022) and practices of the assistant, that is, her work for enabling distributed perception (Due, 2021), but other more salient features take part in the production of the local assembly. The blackboard, the tables, and the chairs are not directly accounted for or oriented to, but are still part of what constitutes this particular phenomenon we are witnessing. The technical apparatus (the equipment and the transcripts) we have applied to capture this phenomenal field only allow a certain view and aspect of the sociomaterial and spatiotemporal multiplicity. But still, from this view, the blackboard, the arrangements of chairs and tables, the placement of equipment, and the rest, all is assembled with the multimodal actions, and all become consequential for the accomplishment of this learning activity.

In terms of practical implications for the design of assistant-supported interactions in the classroom we can conclude, that: 1) learning materials should be made available for visually impaired students in a way that enables a sense of the whole gestalt contexture, and 2) interactions concerning learning should be produced in ways that enable the visually impaired students to engage in the problem identification and solving and not just the calculations and final results. These findings fits nicely within the framework for Universal Design as suggested by Abrahamson et al. (2019).

Appendix

Table 1

Transcription symbols

Table 2

Paper document laying on the table with classroom assignment featuring table

Table 3

Table featured on the professional assistant's computer screen

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Julie H.E. Sandersen for help with data collection.

Declaration of interest statement

This project was funded by Nota. There are no interest conflicts to declare.

References

Abrahamson, D., Flood, V. J., Miele, J. A., & Siu, Y.-T. (2019). Enactivism and ethnomethodological conversation analysis as tools for expanding Universal Design for Learning: The case of visually impaired mathematics students. ZDM, 51(2), 291-303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-0998-1

Antaki, C., & Chinn, D. (2019). Companions' dilemma of intervention when they mediate between patients with intellectual disabilities and health staff. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(11), 2024-2030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.05.020

Antaki, C., & Wilkinson, R. (2013). Conversation Analysis and the Study of Atypical Populations. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), The Handbook of Conversation Analysis (pp. 533-550).

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Second Printing edition). Duke University Press Books.

Blatchford, P., Russell, A., & Webster, R. (2012). Reassessing the impact of teaching assistants: How research challenges practice and policy (1st ed). Routledge.

Bosanquet, P., & Radford, J. (2019). Teaching assistant and pupil interactions: The role of repair and topic management in scaffolding learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(1), 177-190. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12231

Brothers, R. (1973). Arithmetic Computation: Achievement of Visually Handicapped Students in Public Schools. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440297303900713

Butler, M., Holloway, L., Marriott, K., & Goncu, C. (2017). Understanding the graphical challenges faced by vision-impaired students in Australian universities. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(1), 59-72. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1177001

Caldwell, J. E., & Teagarden, K. (2006). Adapting Laboratory Curricula for Visually-Impaired Students. ABLE 2006 Proceedings, 28, 357-361.

Caronia, L. (2018). Following and Analyzing an Artifact: Culture-through-Things. In F. Cooren & F. Malbois (Eds.), Methodological and Ontological Principles of Observation and Analysis (pp. 112-139). Routledge.

Caronia, L., & Cooren, F. (2014). Decentering our analytical position: The dialogicity of things. Discourse & Communication, 8(1), 41-61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481313503226

Chinn, D. (2022). ‘I Have to Explain to him': How Companions Broker Mutual Understanding Between Patients with Intellectual Disabilities and Health Care Practitioners in Primary Care. Qualitative Health Research, 32(8-9), 1215-1229. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323221089875

Chinn, D., & Rudall, D. (2021). Who is Asked and Who Gets to Answer the Health-Care Practitioner's Questions When Patients with Intellectual Disabilities Attend UK General Practice Health Checks with Their Companions? Health Communication, 36(4), 487-496. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2019.1700440

Clamp, S. (1997). Mathematics. In H. Mason, S. McCall, C. Arter, M. McLinden, & J. Stone (Eds.), Visual impairment: Access to education for children and young people (pp. 218-235). David Fulton Publishers.

Due, B. L. (2021). Distributed Perception: Co-Operation between Sense-Able, Actionable, and Accountable Semiotic Agents. Symbolic Interaction, 44(1), 134-162. https://doi.org/10.1002/symb.538

Due, B. L. (2023a). Assemmethodology? A Commentary. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 6(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v6i1.137001

Due, B. L. (2023b). Interspecies intercorporeality and mediated haptic sociality: Distributing perception with a guide dog. Visual Studies, 38(1), 3-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2021.1951620

Due, B. L. (2023c). Ocularcentric Participation Frameworks: Dealing with a blind member's perspective. In P. Haddington, T. Eilittä, A. Kamunen, L. Kohonen-Aho, T. Oittinen, L. Rautiainen, & A. Vatanen (Eds.), Ethnomethodological Conversation Analysis in Motion: Emerging Methods and new technologies. (pp. 63-82). Routledge.

Due, B. L. (2023d). Situated socio-material assemblages: Assemmethodology in the making. Human Communication Research, hqad031. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqad031

Due, B. L. (2024a). An ethnomethodological misreading of Deleuze. Towards Post-praxiology? New Developments in Ethnomethodology: Seoul Workshop. Provocations in and For Ethnomethodology., 1-22.

Due, B. L. (2024b). The matter of math: Guiding the blind to touch the Pythagorean theorem. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 45, 100792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2023.100792

Due, B. L. (2024c). The practical accomplishment of living with visual impairment: An EM/CA approach. In B. L. Due (Ed.), The Practical Accomplishment of Everyday Activities Without Sight (pp. 1-26). Routledge.

Due, B. L. (forth.). The consequentiality of sticky ham salad: A post-praxiological study of visually impaired people's sensory experiences of food items. In W. Gibson, N. Ruiz-Junco, & D. V. Lehn (Eds.), Sensing life: The social organisation of the senses in interaction. Routledge.

Due, B. L., & Lange, S. B. (2018). Semiotic resources for navigation: A video ethnographic study of blind people's uses of the white cane and a guide dog for navigating in urban areas. Semiotica, 2018(222), 287-312. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2016-0196

Due, B. L., & Lüchow, L. (2023). The Intelligibility of Haptic Perception in Instructional Sequences: When Visually Impaired People Achieve Object Understanding. Human Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-023-09664-8

Due, B. L., Sakaida, R., Nisisawa, H. Y., & Minami, Y. (2024). From embodied scanning to tactile inspections: When visually impaired persons exhibit object understanding. In B. L. Due (Ed.), The Practical Accomplishment of Everyday Activities Without Sight (pp. 154-180). Routledge.

Enfield, N. J., & Kockelman, P. (2017). Distributed Agency. Oxford University Press.

Gardner, R. (2015). Summons Turns: The Business of Securing a Turn in Busy Classrooms. In C. J. Jenks & P. Seedhouse (Eds.), International Perspectives on ELT Classroom Interaction (pp. 28-48). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137340733_3

Garfinkel, H. (2021). Ethnomethodological Misreading of Aron Gurwitsch on the Phenomenal Field: Sociology 271, UCLA 4/26/93. Human Studies, 44(1), 19-42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-020-09566-z

Garfinkel, H. (2022). Harold Garfinkel: Studies of Work in the Sciences (M. E. Lynch, Ed.). Routledge.

Giangreco, M. F., Doyle, M. B., & Suter, J. C. (2014). Teacher Assistants in Inclusive Classrooms. In The SAGE Handbook of Special Education: Two Volume Set. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446282236

Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional Vision. American Anthropologist, 96(3), 606-633. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1994.96.3.02a00100

Goodwin, C. (2000a). Action and Embodiment Within Situated Human Interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 32(10), 1489-1522.

Goodwin, C. (2000b). Practices of Color Classification. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 7(1), 19-36. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327884MCA0701&2_03

Goodwin, C. (2007). Participation, Stance and Affect in the Organization of Activities. Discourse and Society, 18(1), 53-74.

Goodwin, C. (2017). Co-Operative Action. Cambridge University Press.

Goodwin, C. (2018). Co-operative action. Cambridge University Press.

Greiffenhagen, C. (2012). Making rounds: The routine work of the teacher during collaborative learning with computers. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 7(1), 11-42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-011-9134-8

Gurwitsch, A. (1964). The Field of Consciousness. Duquesne University Press.

Herold, F., & Dandolo, J. (2009). Including visually impaired students in physical education lessons: A case study of teacher and pupil experiences. British Journal of Visual Impairment, 27(1), 75-84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0264619608097744

Hirvonen, M. I. (2024). Guided by the blind: Discovering the competences of visually impaired co-authors in the practice of collaborative audio-description. In The Practical Accomplishment of Everyday Activities Without Sight. Routledge.

Jakonen, T. (2020). Professional Embodiment: Walking, Re-engagement of Desk Interactions, and Provision of Instruction during Classroom Rounds. Applied Linguistics, 41(2), 161-184. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amy034

Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In Gene H. Lerner (Ed.) Conversation Analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 13-31). John Benjamins Publishing Co.

Jones, N., Bartlett, H. E., & Cooke, R. (2019). An analysis of the impact of visual impairment on activities of daily living and vision-related quality of life in a visually impaired adult population. British Journal of Visual Impairment, 37(1), 50-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0264619618814071

Kendrick, K. H., & Drew, P. (2016). Recruitment: Offers, Requests, and the Organization of Assistance in Interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 49(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2016.1126436

Koole, T. (2010). Displays of Epistemic Access: Student Responses to Teacher Explanations. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 43(2), 183-209. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351811003737846

Koole, T., & Elbers, E. (2014). Responsiveness in teacher explanations: A conversation analytical perspective on scaffolding. Linguistics and Education, 26, 57-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2014.02.001

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation (1ST edition). Cambridge University Press.

Levinson, S. C. (2013). Action Formation and Ascription. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), The Handbook of Conversation Analysis (pp. 103-130). Wiley-Blackwell.

Lüchow, L., Due, B. L., & Nielsen, A. M. R. (2023). Smartphone tooling: Achieving perception by positioning a smartphone for object scanning. In People, Technology, and Social Organization (pp. 250-273). Routledge.

Luff, P., Hindmarsh, J., & Heath, C. (2000). Workplace studies. Cambridge University Press.

Majlesi, A. R. (2018). Instructed Vision: Navigating Grammatical Rules by Using Landmarks for Linguistic Structures in Corrective Feedback Sequences. The Modern Language Journal, 102, 11-29. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12452

Markee, N. (2005). The Organization of Off-task Talk in Second Language Classrooms. In K. Richards & P. Seedhouse (Eds.), Applying Conversation Analysis (pp. 197-213). Palgrave Macmillan.

Mondada, L. (2016). Conventions for Multimodal Transcription. https://franzoesistik.philhist.unibas.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/franzoesistik/mondada_multimodal_conventions.pdf

Mondémé, C. (2020). La socialité interspécifique: Une analyse multimodale des interactions homme-chien. Lambert-Lucas.

Morash, V., & Mckerracher, A. (2014). The Relationship between Tactile Graphics and Mathematics for Students with Visual Impairments. Terra Haptica, 4, 13-22.

Moriña, A. (2017). Inclusive education in higher education: Challenges and opportunities. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32(1), 3-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2016.1254964

Nevile, M., Haddington, P., Heinemann, T., & Rauniomaa, M. (Eds.). (2014). Interacting with Objects: Language, materiality, and social activity. John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://benjamins.com/#catalog/books/z.186/main

Nilsson, E., & Olaison, A. (2022). Persuasion in practice: Managing diverging stances in needs assessment meetings with older couples living with dementia. Qualitative Social Work, 21(6), 1123-1146. https://doi.org/10.1177/14733250221124213

Österholm, J. H., & Samuelsson, C. (2015). Orally positioning persons with dementia in assessment meetings. Ageing and Society, 35(2), 367-388. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X13000755

Pomerantz, A. (1984). Pursuing a response. In J.M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (eds.): Structures of Social Action. Studies in Conversation Analysis. (pp. 152-163). Cambridge University Press.

Radford, J., Blatchford, P., & Webster, R. (2011). Opening up and closing down: How teachers and TAs manage turn-taking, topic and repair in mathematics lessons. Learning and Instruction, 21(5), 625-635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2011.01.004

Rapp, D. W., & Rapp, A. J. (1992). A Survey of the Current Status of Visually Impaired Students in Secondary Mathematics. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 86(2), 115-117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X9208600205

Raudaskoski, P. (2021). Discourse studies and the material turn: From representation (facts) to participation (concerns). Zeitschrift Für Diskursforschung, 2021(2), 244-269.

Raudaskoski, P. (2023). Ethnomethodological conversation analysis and the study of assemblages. Frontiers in Sociology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2023.1206512

Relieu, M. (2024). The production and reception of assistance proposals between pedestrians and visually impaired persons during a course in locomotion and orientation. In B. L. Due (Ed.), The Practical Accomplishment of Everyday Activities Without Sight. Routledge.

Reyes-Cruz, G., Fischer, J. E., & Reeves, S. (2022). Demonstrating Interaction: The Case of Assistive Technology. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction. https://doi.org/10.1145/3514236

Rosenblum, L. P., Ristvey, J., & Hospitál, L. (2019). Supporting Elementary School Students with Visual Impairments in Science Classes. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 113(1), 81-88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X19833801

Sacks, H. L., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation. Language, 50(4), 696-735.

Samuelsson, C., Österholm, J. H., & Olaison, A. (2015). Orally Positioning Older People in Assessment Meetings. Educational Gerontology, 41(11), 767-785. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2015.1039470

Sandersen, J. H. E., Toft, T. L. W., Due, B. L., & Juul, H. (2022). Unge med blindheds brug og oplevelse af elektroniske punktnotatapparater (p. 74).

Schegloff, E. A. (1968). Sequencing in Conversational Openings. American Anthropologist, 70(6), 1075-1095. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1968.70.6.02a00030

Schegloff, E. A. (1984). On questions and ambiguities in conversation. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action. Studies in conversation analysis, studies in emotion and social interaction (pp. 28-53). Cambridge University Press.

Sidnell, J., & Enfield, N. J. (2017). Deixis and the Interactional Foundations of Reference. In Y. Huang (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of pragmatics (First edition, pp. 217-239). Oxford University Press.

Simone, M., & Galatolo, R. (2020). Climbing as a pair: Instructions and instructed body movements in indoor climbing with visually impaired athletes. Journal of Pragmatics, 155, 286-302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2019.09.008

Simone, M., & Galatolo, R. (2021). Timing and Prosody of Lexical Repetition: How Repeated Instructions Assist Visually Impaired Athletes' Navigation in Sport Climbing. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 54(4), 397-419. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2021.1974742

Simone, M., & Galatolo, R. (2023). The situated deployment of the Italian presentative (e) hai. . . , ‘(And) you have. . .' Within routinized multimodal Gestalts in route mapping with visually impaired climbers. Discourse Studies, 25(1), 89-113. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614456221126320

Smith, D. W., & Smothers, S. M. (2012). The Role and Characteristics of Tactile Graphics in Secondary Mathematics and Science Textbooks in Braille. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 106(9), 543-554. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X1210600905

Stivers, T., & Robinson, J. D. (2006). A preference for progressivity in interaction. Language in Society, 35(3), 367-392. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404506060179

Stribling, P., & Rae, J. (2010). Interactional analysis of scaffolding in a mathematical task in ASD. In H. Gardner & M. A. Forrester (Eds.), Analysing interactions in childhood: Insights from conversation analysis (pp. 185-207). Wiley-Blackwell.

Tanner, M. (2014). Lärarens väg genom klassrummet—Lärande och skriftspråkande i bänkinteraktioner på mellanstadiet (Classroom Trajectories of Teaching, Learning and Literacy. Teacher- Student Desk Interaction in the Middle Years). Karlstad University Studies. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kau:diva-31840

Tegler, H., Demmelmaier, I., Johansson, M. B., & Norén, N. (2020). Creating a response space in multiparty classroom settings for students using eye-gaze accessed speech-generating devices. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2020.1811758

University of Copenhagen. (2022). Data Management Policy. https://hum.ku.dk/forskning/datamanagement/Data_management_policy.pdf

Vincenzi, B., Taylor, A. S., & Stumpf, S. (2021). Interdependence in Action: People with Visual Impairments and their Guides Co-constituting Common Spaces. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(CSCW1), 1-33. https://doi.org/10.1145/3449143

Vom Lehn, D. (2010). Discovering ‘Experience-ables': Socially including visually impaired people in art museums. Journal of Marketing Management, 26(7-8), 749-769. https://doi.org/10.1080/02672571003780155

Wiggins, S., & Potter, J. (2003). Attitudes and evaluative practices: Category vs. item and subjective vs. objective constructions in everyday food assessments. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42(4), 513-531. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466603322595257

Wilkinson, R., Rae, J., & Rasmussen, G. (Eds.). (2020). Atypical Interaction: The Impact of Communicative Impairments within Everyday Talk. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28799-3

Markee, Numa (2005): The Organization of Off-task Talk in Second Language Classrooms. In: Keith Richards and Paul Seedhouse (red.), "Applying Conversation Analysis", p. 197-287. New York : Palgrave Macmillan