Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Doing Attending in Multi-Party Dinner Settings:

Static and Dynamic Forms of Attention in French and French Sign Language

Loulou Kosmala1, Claire Danet2, Stéphanie Caët3 & Aliyah Morgenstern4

1Paris-Est Créteil University

2CNRS-LISN

3University of Lille

4University of Sorbonne-Nouvelle

Abstract

In social interaction research, so-called "listeners" are known for being active co-participants of the interaction through several engagement displays, labeled as feedback, backchannel, or listener responses. Enriched by our account of interactions in French and French Sign Language, we suggest using the term 'doing attending' so as to not restrict this practice to a single modality and highlight its functional and interactional nature. Our analyses of video-recorded interactions during family dinners held at home, further demonstrate how such multimodal displays may not always be characterized by 'dynamic' forms, and are deeply shaped by polyadicity as well as co-activity and material affordances, in both languages.

Keywords: listener, attending, engagement, feedback, multi-party interactions, multimodality, sign language

1. Introduction

Face-to-face interactions are characterized by several turn-taking mechanisms and involve dynamic shifts in participation status whereby interactants swiftly move from their role of 'speaker' to their role of 'listener'. While these roles may seem quite unequivocal and straightforward at first, we should not assume that listeners bear a more 'passive' role due to their supposed lack of involvement in the ongoing interaction. As pointed out by Goodwin (1981), so-called listeners have often been neglected in linguistic research, as numerous studies have chosen to focus on the activities of the speakers, who are deemed the main sources of language use. Yet, as Gardner (2001) suggested, listeners can also talk, through various response and feedback tokens. Drawing from a joint study of interactions in French and French Sign Language during family dinners, the present paper continues this line of research, discussing the terms 'listener' and 'listening' and their underlying meanings, as well as the various forms of engagement (including static ones) that can be observed in such multi-party and multi-activity settings.

Research in social interaction, and especially the seminal work of linguistic anthropologists C. and M.H Goodwin (1981, 2010) has reframed the speaker-listener framework and largely used the notion of participation, following Goffman (1981). In their paper entitled "Participation" (Goodwin & Goodwin, 2004) the two authors refrain from conceptualizing listeners as passive interlocutors, but describe them as active co-participants of the interaction, who display different forms of engagement through established participation frameworks. They define participation as "practices through which different kinds of parties build action together by participating in structured ways in the events that constitute a state of talk" (p. 225). In this view, face-to-face interactions, involving two or more conversational participants gathered together at a particular moment in a specific setting, entail complex participation frameworks. Within these frameworks, participants easily shift from one status (e.g. "storyteller") to the next ("attending recipient"), as conversation unfolds. Goffman (1981) initially distinguished between different types of hearers or listeners (i.e. ratified versus non-ratified, addressed versus non-addressed) to deconstruct this monolithic view of passive listeners, and highlight different types of listening behaviors.

The notion of "listening" has received special attention in different fields of research, ranging from conversation analysis, second language acquisition to cognitive linguistics, investigating phenomena gathered under the umbrella term "feedback", also referred to as "backchanneling" (Yngve, 1970), "continuers" (Schegloff, 1982), or "listener responses" (Gardner, 2001; Bavelas et al., 2002), among others. This body of work focuses exclusively on the role of listeners and the types of audible and visible responses they produce to signal attention, interest, or understanding, which may take a variety of forms, such as audible tokens ("mm mm" "yeah" "ok") and visible dynamic features, such as nodding, smiling, frowning, and the like. These displays have also been shown to play an essential role in turn-taking (e.g. Bertrand et al., 2007). In this sense, listening is not merely a sensory faculty but an interactional practice, whereby listeners, acting as active co-participants, offer relevant cues to speakers, who modify their emerging utterances based on their interlocutors' behaviors (Goodwin, 1981).

However, despite this rising interest in the roles of 'listeners' as full-fledged interactants and the multimodal forms of 'listening', the terms themselves remain literally restricted to a single modality involving the auditory output, which is problematic for two reasons. First, so-called spoken languages are built out of an array of semiotic systems which are not restricted to speech (e.g. visual, gestural, and spatial, e.g. Mondada, 2019; Morgenstern, 2022, among others). Second, interactions held among deaf persons in Sign Languages do not rely on vocal resources, but mainly on visual-gestural ones. How can we thus conceptualize the notion underlying the term 'listening' without restricting it to a speaking model? For lack of a better term, we will adopt the terms 'engaging' and 'attending' to refer to recipients' forms of involvement in the course of the interaction, along the lines of Goodwin (1981) and other studies implemented in CA research.

Our study focuses on so-called interlocutors, recipients, or attenders, and the ways in which they demonstrate different forms of engagement in situated interaction, with a focus on French and French Sign Language. Our theoretical framework integrates language socialization theory with interactive and multimodal approaches to language use. We adopt the concept of languaging (Linell, 2009: 274) to encompass the full range of expressive language practices—speaking, gesturing, signing—that individuals draw upon in communication. We focus in particular on how children are socialized into these different modes of expression through their everyday interactions (Ochs, 2012), with a special emphasis on family dinners as rich sites of multimodal engagement that shape language development.

Human beings remain unmatched in their ability to coordinate a wide range of semiotic resources, dynamically adapting their use of relevant behaviors according to the context of interaction, the activity at hand, their addressees' identity, and even temporal factors such as the time of day (Cienki, 2012). Each language offers grammatical tools for encoding aspects of objects and events. Just as children learn "thinking for speaking" by mobilizing the grammatical resources of their native language (Slobin, 1987: 443), we propose that a similar process applies to "thinking for gesturing" or "thinking for signing." In this view, languaging is not only shaped by linguistic and cultural norms but also by the expressive modality through which mental construals are embodied and communicated.

The analyses are based on video-recordings of multi-party interactions held at home during which members of a family are having dinner together, using either French or French Sign Language. In family dinners, language practices can be analyzed as they occur in real life and real time in the framework of multi-party interactions and multi-activity (Haddington et al., 2014). The specificity of family dinners is that participants are constantly handling several activities, namely languaging (Linell, 2009), interacting with one another, and eating, which requires a finely tuned orchestration of their bodies (mouth, hands, arms, eyes, trunk, head) and manipulation of objects (fork, knife, plate, bottle, etc.). When it comes to interactive engagement and feedback behavior, one question emerges: how do recipients signal their engagement while managing different activities at the same time? As this paper will show from the context of family dinners, displaying engagement does not necessarily involve dynamic forms – as previous studies on feedback research have suggested – but also more static ones. We thus regard interaction as inherently shaped by cultural, physiological, interpersonal, as well as environmental and material affordances (Mondada, 2019; Morgenstern & Boutet, 2024).

Our paper is structured as follows: we first provide a selected review of the literature covering studies conducted on backchanneling and feedback in multimodal interactions as well as in Sign Languages, raising the notion of visual attention, followed by a review of studies conducted on engagement, gaze and materiality. We then present the video-data and our methodology for the study of family dinners hold in French and French Sign Language and conduct detailed micro-analyses of six excerpts from the corpus highlighting commonalities in 'doing attending' practices in contexts where several participants language and eat at the same time. Lastly, we discuss and summarize our analyses.

2. Literature Review

As stated earlier, current work in social interaction research has focused not only on the role of main speakers of a conversation but also on recipients. This led researchers to work on specific listener-related phenomena and their engagement displays, known as 'backchanneling', 'feedback', or 'listener response'. The two following sections (sections I and II) review this body of work across spoken and signed interactions, in order to situate these studies in a larger interactional framework encompassing the notions of engagement and participation, through the lens of gaze and co-activity (section III).

2.1 Research on backchanneling, feedback, and listener responses in spoken interactions

The term 'backchannel' was initially coined by Yngve (1980) to refer to brief responses, such as 'yes' 'right', 'uh uh' etc., produced by interlocutors during the main speaker's production, implying two channels of communication: the main channel, and the one produced in the background. This type of approach has been criticized by conversation-analysts, more specifically Schegloff (1982), who preferred the term 'continuers' as to focus on the sequential organization of these short responses within turns, without prioritizing one level over the other. Schegloff defined continuers as signals of "understanding that the other speaker intends to continue talking and passes the opportunity to take the turn" (p. 81). They may also provide opportunities for interlocutors to produce a more extended turn or initiate repair on the prior one. This type of work was then taken up by Goodwin (1986) who spoke of continuers as "bridges between units" (p. 206) whereby the main speaker moves to a next unit of talk while the recipient is acknowledging receipt of the prior. The placement of backchannels/continuers is therefore not random and may occur at "backchannel relevant places" (Heldner et al., 2013), i.e. allocated spaces during the interaction that are relevant to acknowledge the end of a topic, or facilitate the continuation of a narrative.

Other authors have opted for more generic terms, such as "listener responses" which refer to "actions that indicate that the person is attending, following, appreciating, or reacting to the story" (Bavelas et al., 2002: 574). Similarly, the term 'feedback' also involves a broader range of phenomena which pertain to the "success or failure of the interaction" (Allwood et al., 2007) whereby participants acknowledge contact and perception of each other but also display overt signs of understanding or non-understanding. When listing such listener/feedback responses, Gardner (2001) referred specifically to (1) continuers, (2) acknowledgments, (3) newsmarkers, and (4) change-of-activity tokens. Overall, despite differences in terminology (see Xudong, 2009 for an overview of the terms) and classification systems, most studies conducted on multimodal "listening" behavior point to both structural and functional levels of feedback. Feedback responses serve a variety of functions in interaction, namely displaying continued interest (Lambertz, 2011), conveying sympathy (Terrell & Multu, 2012), regulating speech turns (Yamaguchi et al., 2015), or indicating agreement (Ferré & Renaudier, 2017).

Listening or feedback cues typically include vocal tokens, such as "mhm", "yeah", 'ok' or laughter produced in the acoustic channel. However, as Muller (1996: 131) wrote: "listening is an activity that has a global ecology, comprising facial, proxemic, gestural and bodily signals, as well as purely verbal ones". Recent studies have thus typically included both visual-gestural and audio-vocal tokens in their typology. For instance, Ferré and Renaudier (2017) distinguished between unimodal (audible or visible only) and bimodal (combined modalities) types of backchannels. Boudin (2022) offered a multi-layered annotation system including a large set of feedback features, such as prosody, lexicon, syntax, gesture etc. However, these studies of multimodal feedback have been conducted on spoken languages specifically, while these behaviors are also prevalent in sign languages.

2.2 Research on backchanneling, repair, and visual attention in sign languages

Studies in Sign Languages have targeted backchanneling behavior in itself (Mesch, 2016; Fenlon et al., 2013), within the study of specific forms such as the presentation gesture (Engberg-Pedersen, 2002) or the palm-up gesture (McKee & Wallington, 2011), or as part of other interactional phenomena such as other-initiated repairs (Manrique & Enfield, 2015). The focus was on manual productions (e.g. palm-up gestures, the sign for YES) or non-manual1 responses (head nods/shakes, eye blinking, smiles, frowns). Engberg-Pedersen (2002) and McKee and Wallingford (2011) observed that in Danish Sign Language and in New Zealand Sign Language respectively, presentation or palm-up gestures (by themselves or together with non-manual gestures) could present the discourse "as discourse for consideration" (Engberg-Pedersen, 2002), as the addressee reacted to it, either to echo the signer's affect (McKee & Wallingford, 2011) or to signal (dis)agreement, confirmation or negation (Engberg-Pedersen, 2002). Fenlon et al. (2013), investigating the influence of age and gender on backchannel behavior in BSL dyadic conversations, looked at manual forms of backchannel as well as head nods and observed that they could also be used when addressees tried to take the floor. In her description of manual backchannels in Swedish Sign Language, Mesch (2016) showed that backchannel responses could consist in the combination of multiple manual and/or non manual gestures, could overlap with the (main) signer's production, and sometimes repeat (part of) the (main) signer's utterance. Of particular interest for our study is Mesch's observation that backchannel responses can be produced low in space, sometimes outside the signing space, on the signer's laps, often composed of one sign only, with "weak" manual activity (such as lifting a finger), and with no attempt to take the floor. These were especially observed in younger signers.

Feedback has also been studied in the context of repair. Mesch's "weak" manual backchanneling relates to an even subtler form described by Manrique and Enfield (2015) and Manrique (2016) in Argentine Sign Language: the freeze look. This gaze, combined with a still posture, allows the signer to suspend their turn and implicitly prompt the prior speaker to repair or repeat their utterance. Unlike the "thinking face," which signals active formulation of a response, the freeze look is considered an "off-record" strategy (Brown & Levinson, 1987), leaving its interpretation to the interlocutor. Manrique and Enfield link this behavior to Schegloff et al.'s (1977) category of weak repair initiators, which may escalate to more explicit forms over successive turns. While potentially observable in spoken language, this phenomenon likely emerges more clearly in sign languages due to the central role of gaze.

Indeed, sign language research consistently underscores the importance of visual attention. Signers monitor each other's gaze to ensure communicative engagement (Baker, 1977), and even non-addressed participants track turn-taking visually (Beukeleers et al., 2020). Eye gaze is essential for establishing contact, as turns tend to begin with mutual visual alignment, making gaze a crucial "turn regulator" (Mather, 1996: 627). In multi-party settings, gaze coordination becomes even more important. Young signers must learn to manage gaze (Bosworth & Stone, 2021), often with parental scaffolding. Deaf parents employ various "visual-tactile communication strategies" to maintain attention—such as waiting for eye contact, shoulder taps, or waving in the visual field (Loots & Devisé, 2003).

If gazing at the (main) signer is necessary for accessing the discourse content, recipients may also look at the signer to display their engagement in the conversation. As Coates and Sutton-Spence (2001) suggest, gaze direction regulates speaker selection and signals turn boundaries; for instance, signers often look directly at the addressee to yield the floor, while sustained mutual gaze signals readiness to take a turn. Conversely, averting gaze can delay turn initiation, thereby reducing overlap and ensuring orderly exchange. In multi-party settings, gaze is used to select the next speaker, making it a dynamic tool for managing interaction. In addition, gaze also signals comprehension and engagement—serving as a visual backchannel. Thus, if some specific looks may fulfill backchannel functions, such as the freeze look described by Manrique and Enfield (2015), gaze in general plays an important backchanneling role for it informs the signer that other participants are attending the signed languaging.

2.3 Displays of attention and engagement: the role of gaze, space, and materiality in spoken and sign languages

The analysis of backchanneling and feedback, whether in spoken or signed language, highlights the interactive nature of languaging and the active role of the addressee. Participation Framework theory (Goffman, 1981; Goodwin, 1981) emphasizes mutual orientation between speaker and hearer, where recipients are as engaged as speakers. A crucial component in this framework is gaze: directed gaze can indicate engagement or joint attention, while averted gaze may signal disengagement. Gaze patterns hence vary by participant role, with hearers typically gazing more at speakers (Kendon, 1967; Goodwin, 1981). Bavelas et al. (2002) introduced the notion of a "gaze window" as a brief mutual gaze between speaker and hearer during which feedback often occurs. Gaze, along with laughter and other feedback tokens, may also signal appreciation and recipiency (Thompson & Suzuki, 2014). In multi-party interactions, gaze is key for addressee identification and next-speaker selection, and averted gaze may indicate a refusal to take a turn (Auer, 2018).

Spatial arrangements further shape participation and engagement through gaze. According to Kendon (1990), interaction involves a "distinctive spatial-orientational arrangement," or F-formation, maintained throughout the exchange. In sign language settings, this spatial configuration is crucial due to the centrality of gaze. Studies (Tapio, 2018) show that signers adapt space for better visibility, though spatial arrangements can also be constrained by material factors or shaped by participants' histories and embodied experiences.

Such interactions unfold within what Streeck et al. (2011) term a "public semiotic environment" structured by participants' embodied co-presence. Beyond bodily conduct, researchers have highlighted the importance of materiality—tools, artifacts, and documents—as integral resources in interaction (Mondada, 2008, 2019; Nevile et al., 2014).

Gaze, spaces and objects are particularly important in the context of family dinners, where eating practices (i.e., holding a fork, serving a plate full of food etc.) are achieved in relation to the participants' material surroundings including the seating arrangement at the dining table. As Mondada et al. (2021) pointed out, such customs are not decontextualized from language practices and can be made relevant and accountable, "constituting them as publicly available and shareable intersubjective achievements'' (Mondada et al., 2021: 5). Similarly, Morgenstern and Boutet (2024) put forward a multisensory approach to social interaction, especially in contexts of family dinners where interactants manage different activities around the dinner table, handling several objects, preparing and serving food, eating, gesturing or signing. In this view, food and utensils are not mere artifacts, part of the physical setting, but relevant tools integrated in the unfolding interaction.

Following previous work on listeners' responses and participation, we regard feedback as a form of engagement displayed by the recipient to the main speaker/signer in order to convey attention or understanding. However, we argue that displaying one's engagement does not always necessarily involve feedback signals per se, i.e. audible or visual forms (vocal responses, head nods, smiles etc.) in the context of multi-party family dinners where participants are dealing with linguistic and sensorial activities at the same time. To the best of our knowledge, very few studies have investigated feedback behavior in multi-party conversations, except only in experimental settings for computational purposes (e.g. Heylen & Akker, 2007). The present study thus aims to tackle this issue in ecological video-recorded data and compare language resources used in a multimodal language, French, and a visual language, French Sign Language.

3. Data and Methods

The data under study was collected as part of the DinLang project (Morgenstern et al., 2021) funded by the French National Research Agency (ANR) which includes video-recordings of French middle-class families (two parents and two to three children), having dinner in French or French Sign Language. Our goal of gathering real-life annotations in dinner settings also has an impact on the equipment used to record the interactions. The recording set-up aims at capturing as much information as possible without hindering the progression of the dinner. The families were filmed at home with initially two cameras placed at different angles and two microphones in the pilot data. For the rest of the project, three cameras were used with an additional 360° camera placed at the center of the table along with a zoom audio-recorder. The 360° camera allows us to zoom in or out of focus on one or the other participants' bodies. We tried to capture the entire framework, integrating all participants and as much of their languaging, gestures, actions, gaze as possible and to cover the entire space of the activity. The observers set the cameras on tripods and left the room most of the time. Our aim was to deliver a multimodal multilingual archive of participants' coordination of languaging (speaking/signing) and acting with and for each other in French family dinners.

The general design and protocol of the data collection and analyses have been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Sorbonne Nouvelle University. The participants were made fully aware that the research team would have access to the data and that, if they consented, the data, including their faces, could be made accessible to the broader scientific community. We follow the FAIR principles2 for data collection and management.

The analyses presented in this paper draw on qualitative research traditions developed across several theoretical frameworks. While we do not align exclusively with any single approach, our work is informed by perspectives from Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis (EMCA), linguistic anthropology (e.g., Goodwin, 1981), and gesture studies (e.g., Streeck, 2009; Morgenstern, 2014; Cienki, 2017). These fields share a commitment to microanalytic methods, emphasizing close observation of empirical data as it unfolds in situated action. Based on our own annotation system (Parisse et al., 2023) where we distinguished between different levels, namely: (1) audible languaging (i.e., vocal utterances in spoken French) (2) visible languaging (i.e., language productions, whether in French Sign Language or spoken French) (3) acting (actions/activities deployed during the interaction), and (4) gaze direction, we offer a multimodal multi-layered annotation format, inspired by Mondada (2018). We are still in the process of creating a consistent annotation system for French Sign Language and spoken French to account for the temporality of these different levels; the transcription conventions used in this paper are found at the end of the article.

The study uses these two languages in order to compare how participants in similar multi-party dinner settings manage interaction and co-activity through the modalities available to them. Rather than analyzing each corpus in isolation, the aim is to explore how modality-specific affordances may or may not shape practices of languaging, turn-taking, and attention displays.

We present eight multimodal analyses of data fragments from two speaking families and two signing families with children between 3 and 12 years old. We focus more specifically on a range of visible behaviors demonstrating forms of engagement and attention which may or may not include feedback signals.

4. Illustrative Cases of Doing Attending in Spoken French and French Sign Language

In this section, we present detailed analyses of visible displays of Doing Attending, including gaze, still displays as well as dynamic ones, systematically investigating both spoken French and French Sign Language. We take co-activity and materiality into account to show how they may have an effect on multimodal engagement displays in a multi-party interactional format.

4.1 Visible displays of doing attending: examples of still postures

During family dinners, and especially in the present dataset, mothers tended to act as skillful multi-taskers (i.e., serving food, checking on the children, eating, all the while interacting with family members). A previous study conducted on a selection of the data confirmed this observation, as we found a higher proportion of co-activity than languaging alone among two mothers as compared to their child (Chevrefils et al., 2023).

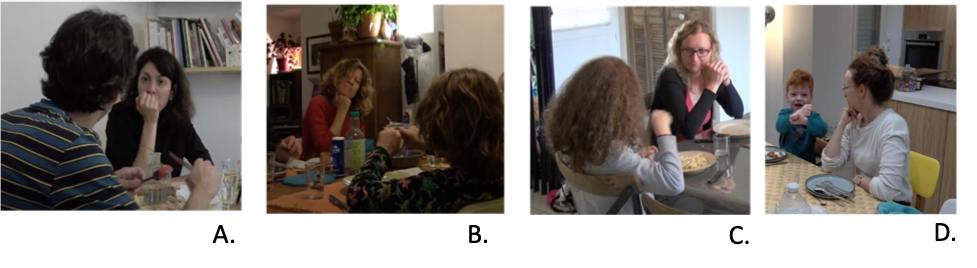

Besides co-activity, we also find instances of doing attending (only) characterized by a still posture, with the head resting on the fist, an occasional head tilt, and gaze fixated on the main speaker. These visible displays are illustrated in the series of screenshots below, in Figure 1. In these examples, most of the mothers are done eating, so they are no longer coordinating between different activities, but rather focusing their full attention on their interlocutor. The first two illustrations on the left (A and B) are taken from French speaking families, and the next ones (C and D) from French Sign Language.

Figure 1. Visible displays of doing attending in the absence of eating across four dinners

In the first example (pic. A), the mother is listening to the father, who is directly addressing her and talking about a funfair held at school; in the second one (pic. B), the mother is not addressed but she is closely attending to her son who is describing an activity he performed at school to his father; in the third example (pic C.), the mother has just finished her plate of pasta and seems to place herself in a kind of 'observer mode' towards her daughter's dining activity. Each example thus explicitly and visibly illustrates cases of focused attention, whereby the mothers are devoted to a single action and a specific speaker/signer, and are no longer attending to their own dining activity. They are also not directly engaged in the interaction, as they do not attempt to initiate a turn, with the exception of the last example (pic. D).

In the last example (taken up in Excerpt 1), the mother has also just finished eating and is intensely engaged in her son's narrative. Her attending posture is marked by her head resting on her right fist, her trunk slightly oriented towards her son and her gaze following his signing. However, unlike the three previous examples (A, B, and C), the mother alternates between different participation statuses, from 'recipient' (head rested on the fist, occasional head nod and one head shake) to 'main signer' (active signing activity), as illustrated in Fig 2. Her son (aged 4 years old) is retelling a story about a police officer who is catching a wolf in order to bring him to prison.

Excerpt 1. Mother's alternating participation status in French Sign Language (DL-LSF1-DIN1)3

Open in a separate window

Three forms of engagement feedback on the mother's part are displayed throughout this excerpt. These forms either emerge in isolation or combination: (1) gaze, (2) head nods, headshakes or manual signs (glossed as YES), and (3) resting positions (chin on hand or hand on table). The mother nods, while resting her chin on her hand, when her son finishes his utterance (Fig 2, line 2). She then takes her turn (Fig 2, line 3) and engages in the narrative, assisting her son who is trying to produce a rather complex linguistic construction that requires the use of specific handshapes to refer to specific (classes of) referents in a dynamic relation to each other. After she has finished signing, she keeps her arm and hand on the table in a resting position (Fig 2, line 4), and her gaze, along with her shoulder and head orientation, seems to be the only indicator of engagement at this moment. After reformulating her son's utterance a second time (line 5), she nods again (line 6), although her son is not looking at her directly (he may be able to see her in his peripheral field of vision however). Placing her hands on the table (line 8), she then both nods and produces the manual sign for YES (line 8) when their eyes meet. Finally, she resumes her full Doing Attending activity by placing her fist under her chin one more time (Fig 2, line 9), using head and facial expressions to express alignment with her child and frame the end of his narrative.

While a majority of studies conducted on feedback or backchannel processes have mostly focused on 'dynamic' forms of engagement (nodding, smiling, frowning etc.) this example reveals that gaze or posture alone (which could be characterized as static) may also function as feedback, or doing attending. This point will be elaborated further in other examples. In addition, this chin-on-hand attending posture may be a way for the mother to clearly signal her attention to her son as recipient, with no overt wish for change in signer status. In particular, her chin-on-hand posture was displayed at the beginning and the end of her son's narrative, at what may be considered, at the discursive level, as "backchannel relevant places" (Heldner et al., 2013).

4.2 Doing attending through gazing, nodding, and co-activity

While the first examples have illustrated the ways in which mothers may display engagement through static postures of 'Doing Attending' whereby they solely rely on a single activity, Excerpt 2 illustrates the possible impact of co-activity on such engagement displays. This example is taken from a different signing family, in which the father is interacting with his daughter, aged 6, who is narrating about her getting lost in the school. The father closely attends to what his daughter is signing, which can be observed in his gaze behavior and head movement. As illustrated in Figure 3, the father carefully alternates between gazing towards his plate and attending to his daughter's production: the conduct of two activities (eating and interaction) seems to influence and hence shape his feedback behavior. Indeed, he keeps his head still and does not nod when he is gazing towards his plate at first, but then constantly shifts his gaze back and forth between his daughter and his plate, nodding at the end of utterances marking transitions in the narrative structure (problem-being lost, and stuck line 2; trying solutions-trying to open door line 6, with new problems-line 7).

Excerpt 2. Father's co-activity in French Sign Language (SF-F2)

Open in a separate window

A few seconds later in this sequence, as depicted in Figure 4 (line 8 of the transcription), the father maintains his engagement while eating, by continuously nodding when redirecting his gaze towards his plate. This example shows how the father manages successfully to alternate between eating and interacting through a variety of engagement displays (gaze and/or nods).

Similarly, in the next example, taken from a French speaking family, the father displays an alternating gazing behavior while in co-activity.

Excerpt 3. Father's co-activity in spoken French (DL-FRA4-DIN1)4

Open in a separate window

In this excerpt, taken from spoken French, the whole family is talking about Notre Dame de Paris and its reconstruction following the fire that took place a couple of years before. The oldest child (aged 12) has taken the turn and is reporting extensively on the discussion she had with her school teacher (pseudonymized as Mr Jefferson). Throughout her turn, she mostly gazes mid-space, but also extensively towards her mother, who is sitting opposite her. Meanwhile, the father, who is attending to his dining activity, is also alternating his gaze on his plate, on the mother and on his daughter (see Fig. 5). Unlike the previous example, the father does not produce any 'dynamic' form of feedback (e.g. nodding) but exclusively relies on his gaze to attend to his daughter's talk.

First, the father is fully focused on his eating activity as his gaze is continuously directed towards his plate (l.1) until it shifts to his daughter (l.2) as she introduces a contrasted element ('but at the same time'), before he looks back at his plate and resumes his eating activity. He then quickly glances in mid space, then back towards his plate, and (l.4) towards the mother as the daughter utters the word 'history'. The father gazes back at the daughter on line 6 as she expresses her personal thoughts ('I think that') but as she reports her teacher's speech on line 7 he redirects his gaze towards his hands and his napkin. Finally, towards the end of the daughter's turn, the father maintains his gaze in her direction, and gazes back at the mother after a nod, paving the way for his agreement expressed in the subsequent turn (l. 10) overlapping with the mother. In sum, in this sequence, the father has relied extensively on his gazing behavior to punctually display or claim forms of understanding and engagement towards his daughter, while engaged in an eating activity which also required his attention. He was able to manage both activities at the same time, but also to include the mother in the participation framework whose gaze was also alternating between the activities of eating and attending conversation.

4.3 Doing attending through directed gaze and suspension of current activity

Previous excerpts showed how participants coordinate eating, interacting, and displaying attention through gaze and nods in multi-party settings. In contrast, the next examples highlight moments when coordination breaks down, and one activity is temporarily suspended through holds. Gesture research has long studied gesture holds—pauses in manual movement either before or after the stroke phase (Kendon, 2004; McNeill, 1992; Kita, 1993). These holds can serve interactive or turn-transitional functions, such as marking a question and waiting for a response (Kendon, 1995; Mondada, 2007) or resolving misunderstandings (Sikveland & Ogden, 2012). Lepeut (2022), examining holds in both French Belgian and French Belgian Sign Language, found similar functions across modalities, including turn-holding, monitoring, and collaborative word searches.

Most studies focus on the speaker's or signer's perspective, with fewer addressing recipients' roles (but see Groeber & Pochon-Berger, 2013). Moreover, while gesture holds are analyzed as linguistic suspensions, less attention has been paid to the suspension of concurrent activities, which characterizes multi-task interaction.

The first example (Excerpt 4) is taken from a French Speaking family and the second one (Excerpt 5) from a French Signing Family. In Excerpt 4, the father is interacting with his youngest son, aged 4, who is talking about a man from kindergarten.

Excerpt 4. Father's suspended eating activity in spoken French (FD-F4)

Open in a separate window

In Excerpt 5, the mother is interacting with her daughter, aged 7, who is signing about a woman from school.

Excerpt 5. Mother's suspended eating activity in French Sign Language (DL-LSF1-DIN1)

Open in a separate window

In Excerpt 4, the father briefly holds the spoon with his left hand and the avocado with his right hand while attending to what his son is saying (Fig. 6, line 3 of the first transcription). He only resumes his dining activity when he takes the turn (l. 4) to initiate an other-repair, more specifically a restricted request ("c'est qui Michel?"), and changes participation status. Similarly, although at a different sequential position in Excerpt 5, we can observe that the mother, after a sequence of nods (line 1 and beginning of line 2 of the transcription) momentarily holds her spoon while attending to what her daughter is signing (Fig. 7, middle of line 2). For a short moment her whole body freezes as she neither signs nor produces other feedback signals (e.g. nodding, frowning). Then, right before resuming her dining activity, she produces a non-manual feedback signal, a frown (end of line 2), and takes the turn (l. 3).

In both cases, the suspending activity occurs as children are producing complex sequences that require specific attention (a 4-year-old narrative productions which are difficult to understand in Excerpt 4). In Excerpt 5, manual spelling is also used. These two examples reveal a shift in participation status, from feedbacker to languager, marked by a suspension of acting, which illustrate a form of engagement that does not necessarily involve dynamic feedback cues (i.e. nods, smiles and the like). We can assume that in a multi-activity situation, certain static forms function as markers of interactional engagement and can also be considered as feedback signals to a certain extent. These examples have also highlighted the importance of materialities when suspending actions; suspending one's body may thus also involve external objects and artifacts, which leads us to the final example. Mutual gaze is also of relevance here: in both examples, the parents' suspending activities coordinated with their children's mutual gaze as they were finishing their current turn. This further shows the relationship between recipients' suspended actions and the main speakers/signers' activities (Mortensen & Hazel, 2024).

4.4 Adjustment of the material environment for Doing Attending

As Mondada et al. (2021:4) wrote: "sensory practices can be mobilized and made relevant at any point and in a fleeting way". Family dinners revolve around sensory practices (tasting and smelling the food, serving a glass of water, grabbing the salt from across the table etc.) which may not seem to be directly related to the interaction at first, but which, in some cases, play an integral part in the interaction. The final example, taken from another French Signing family, demonstrates the importance of visual space, and how participants may wish to adjust their spatial environment for visual attention. Here the father is about to engage with his daughter on his left (Figure 8) but he first slightly moves the bottle to the side before yielding her the turn.

Excerpt 6. Father adjusting environment to enable attention in Signing Family (SF-F8)

Figure 8. Father adjusting environment to enable attention in Signing Family (SF-F8)

To ensure visual access to each other during signed interaction, co-participants often adjust the physical environment. In this case, the father moves a bottle aside to create an unobstructed visual space, enabling him to fully engage with his daughter. This reflects the earlier discussion on visual attention, especially in material, multi-activity settings. Manrique and Enfield (2015: 220) note that signers typically minimize multitasking to maintain focused interaction. However, signed communication often occurs alongside tasks requiring object manipulation or divided attention. Tapio (2018), studying classroom settings involving both physical and virtual spaces, highlighted how gaze coordinates action and supports the development of stable "attention structures." While the setting here differs, it similarly shows how even small adjustments—like moving a bottle—can serve interactional purposes, facilitating turn-taking and visible engagement.

5. Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to discuss forms of 'listening' or, rather, 'doing attending' across spoken and signed conversations, based on a series of examples taken from multi-party interactions during family dinners which are deeply situated in material affordances. We identified recurrent visible displays of Doing Attending across several examples taken from different dinners, which suggest that this practice, also in its static form, is a publicly visible and conventionalized act, which may be interpreted as such by speakers and signers. This invites us to further reflect on the dynamic and fleeting nature of interaction itself, which does not restrict interactants to a single participation status.

While a growing number of studies have been conducted on the active participation of so-called "listeners" and their range of feedback and listener responses in talk-in-interaction, including multimodal dynamic tokens (mm mm, ok, head nods, raised eyebrows), less is known about the manifestation of such displays in relation to co-activity in multi-party interactions. In Excerpts 2 and 3, we showed that co-activity could potentially have an impact on attenders' behaviors, who have to alternate between different gazing and nodding behaviors to better coordinate their actions. In other cases (Excerpts 4 and 5), the dining activity had to be momentarily suspended to better engage in the doing attending activity.

The complexity of the data under study, which comprises multi-activity and multi-party interactions in an embodied material environment, also invites us to reflect on the forms of engagement (including static forms) and the extent to which they may be considered as active displays. Thus, the act of doing attending is not a merely passive one, left unnoticed, restricted to a single modality, but an intricate interplay of embodied practices (hearing/listening, seeing/looking, moving) embedded within multiple activities in situated discourse. Our analyses have shown that displaying one's engagement does not always necessarily involve feedback signals per se, i.e. audible or even dynamic forms, especially in the context of multi-party family dinners where participants are dealing with inter-actional and sensorial activities at the same time. Gaze, as shown in previous studies, also plays a fundamental role for signaling attention, and enabling visual attention may be interactionally crucial, especially in signed conversations (Excerpt 6) but also for signalling and/or maintaining focused attention and appreciative recipiency. We believe that the concurrent analysis of spoken (or, rather, multimodal) and signed languages will continue enlightening our understanding of the role of gaze and movement in face-to-face interactions.

While our analyses were primarily based on the parents' practices and their skillful orchestration of languaging, dining, and attending activities throughout the dinners, it opens up perspectives for the study of children's development of that interactional competence, and their range of doing attending behaviors. In this sense, the family dinner setting emerges as a rich and dynamic site for observing how participants negotiate attention, participation, and meaning in real time. Future research building on this approach may further illuminate how listening—whether through speech, sign, or embodied stillness—constitutes a fundamental dimension of human sociality and interaction.

Appendix – Transcription conventions:

Subscript characters attached to the participants' labels:

| al: | line for audible languaging |

| vl: | line for visible languaging (additional lines for articulators when relevant e.g., 'hand' 'head', and 'face') |

| act: | line for actions |

| g: | line for gaze |

| free: | line for free translation from LSF to English |

Symbols for temporality (Mondada, 2018):

| * *: | delimitation of the start and end of languaging/actions/gaze |

| —-----: | languaging/action/gaze maintained |

| —--->: | when an languaging/action/gaze continues across subsequent lines |

Transcription symbols for spoken interactions (Jefferson, 2004):

| wo::rrd : | prolonged vowel or consonant |

| (( )) : | analysts' comments |

| (.) : | a pause |

| [ ] : | speech overlaps |

| = : | indicates continuity between the same speaker's utterance. |

| - : | cut-off |

References

Allwood, J., Cerrato, L., Jokinen, K., Navarretta, C., & Paggio, P. (2007). The MUMIN coding scheme for the annotation of feedback, turn management and sequencing phenomena. Language Resources and Evaluation, 41(3), 273–287.

Auer, P. (2018). Gaze, addressee selection and turn-taking in three-party interaction. In G. Brône & B. Oben (Eds.), Advances in Interaction Studies (Vol. 10, pp. 197–232). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/ais.10.09aue

Bavelas, J. B., Coates, L., & Johnson, T. (2002). Listener responses as a collaborative process: The role of gaze. Journal of Communication, 52(3), 566–580.

Beukeleers, I., Brône, G., & Vermeerbergen, M. (2020). Unaddressed participants' gaze behavior in Flemish Sign Language interactions: Planning gaze shifts after recognizing an upcoming (possible) turn completion. Journal of Pragmatics, 162, 62–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.04.001

Bosworth, R. G., & Stone, A. (2021). Rapid development of perceptual gaze control in hearing native signing Infants and children. Developmental Science, 24(4), e13086. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.13086

Boudin, A. (2022). Interdisciplinary corpus-based approach for exploring multimodal conversational feedback. Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, 705–710.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge university press.

Chevrefils, L., Morgenstern, A., Beaupoil-Hourdel, P., Bedoin, D., Caët, S., Danet, C., Danino, C., de Pontonx, S., & Parisse, C. (2023). Coordinating eating and languaging: The choreography of speech, sign, gesture and action in family dinners. GeSpIn 2023: 8th Gesture and Speech in Interaction Conference.

Cienki, A. (2012). Usage events of spoken language and the symbolic units we (may) abstract from them. In Janusz Badio & Krzysztof Kosecki (Eds), Cognitive processes in language (pp. 149-158). Peter Lang.

Cienki, A. (2017). Utterance Construction Grammar (UCxG) and the variable multimodality of constructions. Linguistics Vanguard, 3(s1).

Coates, J., & Sutton‐Spence, R. (2001). Turn‐taking patterns in deaf conversation. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 5(4), 507–529. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9481.00162

Engberg-Pedersen, E. (2002). Gestures in signing: The presentation gesture in Danish Sign Language. In R. Schulmeister & H. Reinitzer (Eds.), Progress in sign language research: In honnor of Siegmund Prillwitz. Signum.

Fenlon, J., Schembri, A., & Sutton-Spence, R. (2013). Turn-taking and backchannel behaviour in BSL conversations.

Ferré, G., & Renaudier, S. (2017). Unimodal and bimodal backchannels in conversational english. SEMDIAL 2017, 27–37. https://hal.science/hal-01575230/

Gardner, R. (2001). When Listeners Talk. In Pbns.92. John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://benjamins.com/catalog/pbns.92

Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Goodwin, C. (1981). Conversational Organization: Interaction Between Speakers and Hearers. Academic Press.

Goodwin, C. (1986). Audience diversity, participation and interpretation. Text - Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse, 6(3). https://doi.org/10.1515/text.1.1986.6.3.283

Goodwin, C. (2010). Multimodality in human interaction. Calidoscopio, 8(2).

Goodwin, C., & Goodwin, M. H. (2004). Participation. A Companion to Linguistic Anthropology, 222–224.

Haddington, P., Keisanen, T., Mondada, L., & Nevile, M. (Eds.). (2014). Multiactivity in Social Interaction: Beyond multitasking. John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.187

Heldner, M., Hjalmarsson, A., & Edlund, J. (2013). Backchannel relevance spaces. Nordic Prosody XI, Tartu, Estonia, 15-17 August, 2012, 137–146.

Heylen, D., & op den Akker, R. (2007). Computing backchannel distributions in multi-party conversations. Proceedings of the Workshop on Embodied Language Processing, 17–24.

Kendon, A. (1967). Some functions of gaze-direction in social interaction. Acta Psychologica, 26, 22–63.

Kendon, A. (1990). Conducting interaction: Patterns of behavior in focused encounters. Cambridge University Press.

Kendon, A. (1995). Gestures as illocutionary and discourse structure markers in Southern Italian conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 23(3), 247–279.

Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible action as utterance (Cambridge University Press). Cambridge University Press.

Kita, S. (1993). Language and thought interface: A study of spontaneous gestures and Japanese mimetics. University of Chicago.

Lambertz, K. (2011). Back-channelling: The use of yeah and mm to portray engaged listenership. Griffith Working Papers in Pragmatics and Intercultural Communication, 4(1/2), 11–18.

Lepeut, A. (2022). When hands stop moving, interaction keeps going: A study of manual holds in the management of conversation in French-speaking and signing Belgium. Languages in Contrast.

Linell, P. (2009). Rethinking Language, Mind, and World dialogically: Interactional and Contextual Theories of Human Sense-Making. Information Age Publishing.

Loots, G., & Devise, I. (2003). An intersubjective developmental perspective on interactions between deaf and hearing mothers and their deaf infants. American Annals of the Deaf, 148(4), 295–307.

Manrique, E. (2016). Other-initiated Repair in Argentine Sign Language. Open Linguistics, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2016-0001

Manrique, E., & Enfield, N. J. (2015). Suspending the next turn as a form of repair initiation: Evidence from Argentine Sign Language. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(1326), 1–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01326

Mather, S. (1996). Initiation in visually constructed dialogue. Multicultural Aspects of Sociolinguistics in Deaf Communities, 109–131.

McNeill, D. (1992). Hand and mind: What gestures reveal about thought. University of Chicago press.

McKee, R., & Wallingford, S. (2011). 'So, well, whatever': Discourse functions of palm-up in New Zealand Sign Language. Sign Language & Linguistics, 14(2), 213–247. https://doi.org/10.1075/sll.14.2.01mck

Mesch, J. (2016). Manual backchannel responses in signers' conversations in Swedish Sign Language. Language & Communication, 50, 22–41.

Mondada, L. (2007). Multimodal resources for turn-taking: Pointing and the emergence of possible next speakers. Discourse Studies, 9(2), 194–225.

Mondada, L. (2008). Production du savoir et interactions multimodales. Revue d'anthropologie Des Connaissances, 2(2), 219–266.

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85–106.

Mondada, L. (2019). Contemporary issues in conversation analysis: Embodiment and materiality, multimodality and multisensoriality in social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 145, 47–62.

Mondada, L., Bouaouina, S. A., Camus, L., Gauthier, G., Svensson, H., & Tekin, B. S. (2021). The local and filmed accountability of sensorial practices: The intersubjectivity of touch as an interactional achievement. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 4(3), 30.

Morgenstern, A. (2014). Children's multimodal language development. Manual of Language Acquisition, 123–142.

Morgenstern, A. (2022). Children's multimodal language development from an interactional, usage-based, and cognitive perspective. WIREs Cognitive Science, 14(2), e1631. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1631

Morgenstern, A., & Boutet, D. (2024). The Orchestration of Bodies and Artifacts in French Family Dinners. In T. Breyer, A. M. Gerner, N. Grouls, & J. F. M. Schick (Eds.), Diachronic Perspectives on Embodiment and Technology (Vol. 46, pp. 111–130). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-50085-5_8

Morgenstern, A., Caët, S., Debras, C., Beaupoil-Hourdel, P., & Le Mené, M. (2021). Children's socialization to multi-party interactive practices. In L. Caronia (Ed.), Language and Social Interaction at Home and School (pp. 45–86). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Mortensen, K., & Hazel, S. (2024). The Temporal Organisation of Leaning in Social Interaction. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 7(4).

Müller, F. E. (1996). Affiliating and disaffiliating with continuers: Prosodic aspects of recipiency. Prosody in Conversation: Interactional Studies, 12, 131.

Nevile, M., Haddington, P., Heinemann, T., & Rauniomaa, M. (2014). Interacting with objects: Language, materiality, and social activity. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Ochs, E. (2012). Experiencing language. Anthropological Theory, 12(2), 142-160.

Parisse, C., Blondel, M., Caet, S., Danet, C., De Pontonx S., & Morgenstern, A. (2023) Création et codage d'un corpus multimodal de repas familiaux. In Journées de Linguistique de Corpus. 3-7 July 2023. Grenoble, France.

Schegloff, E. A. (1982). Discourse as an interactional achievement: Some uses of 'uh huh'and other things that come between sentences. Analyzing Discourse: Text and Talk, 71, 93.

Schegloff, E. A., Jefferson, G., & Sacks, H. (1977). The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. Language, 53(2), 361–382.

Sikveland, R. O., & Ogden, R. (2012). Holding gestures across turns: Moments to generate shared understanding. Gesture, 12(2), 166–199.

Slobin, D. (1987). Thinking for speaking. Proceedings of the Thirteenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 435-445.

Stivers, T., & Rossano, F. (2010). Mobilizing Response. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 43(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810903471258

Streeck, J. (2009). Gesturecraft: The manu-facture of meaning (Vol. 2). John Benjamins Publishing.

Streeck, J., Goodwin, C., & LeBaron, C. (2011). Embodied interaction: Language and body in the material world. Cambridge University Press.

Streeck, J., & Hartge, U. (1992). Gestures at the transition place. In P. Auer & A. Di Luzio (Eds.), The contextualization of language(pp. 135–157). John Benjamins Publishing.

Tapio, E. (2018). Focal social actions through which space is configured and reconfigured when orienting to a Finnish Sign Language class. Linguistics and Education, 44, 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2017.10.006

Terrell, A., & Mutlu, B. (2012). A regression-based approach to modeling addressee backchannels. Proceedings of the 13th Annual Meeting of the Special Interest Group on Discourse and Dialogue, 280–289. https://aclanthology.org/W12-1639.pdf

Thompson, S. A., & Suzuki, R. (2014). Reenactments in conversation: Gaze and recipiency. Discourse Studies, 16(6), 816–846.

Xudong, D. (2009). Listener response. The Pragmatics of Interaction, 4, 104.

Yamaguchi, T., Inoue, K., Yoshino, K., Takanashi, K., Ward, N. G., & Kawahara, T. (2016). Analysis and prediction of morphological patterns of backchannels for attentive listening agents. Proc. 7th International Workshop on Spoken Dialogue Systems, 1–12.

Yngve, V. H. (1970). On getting a word in edgewise. Papers from the Sixth Regional Meeting Chicago Linguistic Society, April 16-18, 1970, Chicago Linguistic Society, Chicago, 567–578.

1 In the sign language literature, "manual gestures" refer to gestures performed with the upper-limbs including the arms and shoulders and are not restricted to the hands. Non-manual gestures refer primarily to gestures involving the head, the torso and to facial expressions.↩

2 Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (Wilkinson et al., 2016)↩

3 Transcription conventions are found in the Appendix. For French Sign Language, we propose free translations (after XXXfree), as well as glosses (after XXXvl). For some sign languages, ID-glosses can be used for transcription purposes (ID-gloss are unique sign labels, corresponding to lemmas; labels are extracted from the written system of the surrounding vocal language, but ID-gloss are not translations: ID-gloss relate to the form of the signs, not to their -contextual- meaning). Because there is no signbank in LSF with ID-gloss and because LSFB is close to LSF, we use ID-gloss (in upper-case letters) from the LSFB corpus (https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/lexique.php) that we translate into English (with wordings that could be close to ID-gloss in English on the Global SignBank : https://signbank.cls.ru.nl/ when possible; for example, the label PRISON was chosen over JAIL because PRISON is an English ID-gloss in the Global SignBank). Glosses are used to annotate conventional lexical signs. Other constructions (pointing, classifier constructions, constructed actions…) are annotated based on their meaning, that we describe using lower-case letters; no other linguistic information is added in order to facilitate the access to the annotations by non-specialist readers of the journal.↩

4 Spoken transcriptions include utterances from the original language as well as English translations (in italic).↩