Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Missing Responses as an Interactional Warning Sign:

Miscommunication and Divergent Temporal Prioritisations in Moments of Decision-Making in Military

Observer Training

Antti Kamunen & Iira Rautiainen

University of Oulu

Abstract

In this study, we aim to find out what happens in moments of collaborative situations when a response is treated as missing, irrelevant, or insufficient, how such moments are handled, and what underlying interactional trouble those instances can reveal. The data are video recordings from multinational military observer training. Using the method of ethnomethodological conversation analysis (EMCA), we examine a team of two people taking part in a simulated patrolling exercise. We focus on instances when one team member, the driver, attempts to get the other, the team leader, to verbalise or confirm some decision regarding a future (joint) action.

Keywords: collaborative work, military crisis management, missing responses, progressivity, training

1. Introduction

In collaborative situations, much of decision-making requires negotiation among the participants. In this study, we examine a professional training context, focusing on moments of decision-making in collaborative situations during a UN Military Observer Course. The examined context is highly task-oriented, and therefore what becomes topicalised is mostly related to progressing the joint activity. Furthermore, it is a learning context, foregrounding the normative obligation to perform a particular type-fitted response at the first possible opportunity (Schegloff, 1968). By analysing interactional moments of one military observer trainee team taking part in a vehicle patrolling exercise, we show what happens when, at a critical time in the joint activity, a relevant, projected response is missing, how such moments are handled, and what underlying interactional trouble those instances can indicate.

The data for the study are video recordings from a multinational United Nations military observer training course. The interaction in the course differs somewhat from what has traditionally been seen as characteristic of military discourse: despite its institutionality and the military hierarchies and rank system, the participants are all peers in their role as learners, and thus the course is organised as a "no-ranks course". Using the method of ethnomethodological conversation analysis (EMCA, Garfinkel, 1967; Sidnell & Stivers, 2013; Eilittä et al., 2023), we examine a team of two people participating in a simulated patrolling exercise (for studies on simulated training contexts, see e.g., Hindmarsh et al., 2014; Koskela & Palukka, 2011). The broader activity of patrolling consists of a variety of sub-activities or tasks, and progressing the overall activity involves progressing all of these connecting tasks. Oftentimes, several tasks require the attention of the participants simultaneously, and due to coinciding tasks, participants may occasionally need to manage and progress actions and courses of action that occur simultaneously (Haddington et al., 2014). In this paper, we focus on moments when one team member, the driver, attempts to get the other, the team leader, to verbalise or confirm an imminent next (joint) action. In our data, such requests for instruction or direction most often occur in connection with moments when a decision needs to be made for the team.

The paper sets out to answer the following research questions:

- How does a missing or delayed response affect the team's decision-making?

- What are the participants' methods for dealing with a missing or delayed response?

- What, if anything, do missing or delayed responses indicate about the overall interactional dynamics?

2. Missing Responses, Progressivity, and Decision-Making in Joint Activity

As shown already in the seminal paper by Sacks and colleagues (1974), the relevance of producing a response when addressed a question is considered a part of the basic systematics of turn-taking. This, like other adjacency pair sequences, is the basic sequential structure in interaction, and fundamental for the social organisation of action. It has also been shown that there is a preference for actions that maximise cooperation and minimise conflict in conversation (Atkinson & Heritage, 1984). The concept of progressivity is closely connected to the advancement of social actions at the sequential level as well as the level of developing courses of action. In the following, we will briefly introduce previous work on progressivity and the role of type-fitted responses in advancing interaction. Furthermore, we will discuss their meaning for decision-making and introduce relevant research on the topic.

Progressivity relates to the "nextness" or adjacency (Schegloff, 2007) of various interactional components such as syllables, words, and turn-constructional units, as well as larger entities, such as sequences, courses of action, and overall projects. At the turn level, for example, self-initiated self-repairs (Schegloff, 1979) and ways of handling word searches (M. H. Goodwin & C. Goodwin, 1986) have been found to demonstrate participants' orientation to the turn's progression. At the sequence level, according to Stivers and Robinson (2006), the preference for progressivity is manifested in actions that work towards closing the sequence. Moreover, Schegloff (2007) has shown the preference for responses that further the action initiated by the first-pair part. Should the relevant next action be delayed or missing, the progressivity of the course of action can be restored or enforced by pursuing a response or by, for example, using imperative directives (Kent & Kendrick, 2016). EMCA research has mainly focused on progressivity at these local levels; the interactional organisation of in-progress activities and the development of actions at the level of turn construction and sequence structure (see, e.g., Amar et al., 2021; Heritage, 2007; Schegloff, 2007; Stivers & Robinson, 2006). In this study, we take a more extensive approach and examine participants' ways of furthering the ongoing activity and their orientation to the progressivity of the overall patrolling activity (see Rautiainen, 2022).

The interactional work done at the sequential level is, of course, influential in furthering the overall activity. Previous studies have shown the existence of a normative obligation for interlocutors to produce a type-fitted response at the first possible opportunity (see Stivers & Rossano, 2010; Schegloff, 1968). When a response is missing, speakers typically orient to it as a failure (Stivers & Rossano, 2010). Previous research has mainly focused on strategies participants resort to when pursuing a relevant response (Bolden et al., 2012; Pomerantz, 1984; Stivers & Rossano, 2010). For example, Pomerantz (1984) has examined how speakers modify or review their utterances in order to get a response. In a similar vein, Bolden and colleagues (2012, p. 138) have shown that "the way in which response is pursued may reveal the speaker's analysis of what the trouble in providing a response might be". A response can also be considered inadequate. According to Bolden and colleagues (2012, p. 145), "[f]aced with a second pair-part turn by another, the recipient of that turn can assess it for its adequacy as a response to the initiating action". For example, a response can be unpreferred, unfitting, irrelevant, or minimal. Practices for pursuing missing or inadequate responses range from discreet to overtly marked (e.g., Jefferson, 1981; Lerner, 2004; Bolden et al. 2012). Pomerantz (1984) has shown that by reviewing or modifying the utterance (e.g., word selection, accuracy, or content) the speaker can pursue a response, and the success of these pursuits lies in whether the recipient voices their agreement or disagreement. Similarly, Sidnell (2010, p. 64) has noted that the speaker's orientation to a missing response becomes visible in three commonly produced types of subsequent conduct: pursuit, inference, and report. Often, the person not producing the response also orients to the response as missing, and produces an account for not responding (Sidnell, 2010). To sum up, missing responses are seen as indications of some kind of trouble in interaction and they are, therefore, something that is either accounted for by the person not producing the response or pursued by the first speaker. Much of the previous research has examined missing responses in everyday settings, yet not much is known about how missing responses are handled in institutional or learning settings. The present study aims to fill this research gap by investigating missing responses in the context of a unique professional training setting where timely and type-fitting responses are crucial for the participants' successful carrying out of their tasks.

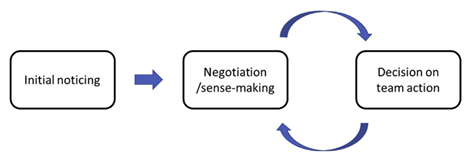

A smooth progression of interactional sequences is crucial for negotiating a decision which can, in its simplest form, comprise an adjacency pair of proposal and acceptance. This trajectory can be further extended by inserting new sequences, thus forming a sequence of sequences (Schegloff, 2007, p. 252), which allows moving from a proposal to a joint decision that – to be genuinely considered joint – requires more than just an instant acceptance. In the cases we investigate in this paper, most of the first-pair parts are requests for information – or requests for instruction – regarding an imminent future action. Those turns concern and (attempt to) initiate a process of making – or confirming – a decision on what to do or where to go next. According to Huisman (2001), decision-making episodes can emerge in interaction through exchanges of opinions and information, in which participants "jointly construct the formulation of states of affairs, and through further assessment and formulation build commitment to particular future states of affairs" (Huisman, 2001, p. 75). In a deontically asymmetrical dyad (Stevanovic, 2012), one participant has "the final say" on the participants' joint actions. According to Stevanovic (2012), joint decision-making consists of consecutive steps that recipients go through, which include access to the content of the proposal, agreement with the proposer's view, and commitment to the proposed future action (Stevanovic 2012, p. 781). These steps are also hierarchically ordered, and each respective step is a prerequisite for the next one. Decision-making sequences in more formal (and non-mobile) organisational contexts, such as meetings or workshops, are usually seen to begin with a proposal for future joint action (Stevanovic, 2012; Magnusson, 2021) or a formulation of the state of affairs (Huisman, 2001). In the complex and mobile training context of this study, though, such processes usually begin once new, potentially relevant information (e.g., an intersection, a minefield, previously unknown weapons or troops) suddenly becomes accessible to the team due to their movement in the area (see Haddington et al., 2022; Kamunen et al., 2022). Here, the decisions concern immediate matters that do not leave time for much negotiation but merely require confirmation or instruction regarding the next action. The process thus resembles the one described by Kamunen and colleagues (2022), where an initial observation or noticing leads to a sense-making process regarding what the situation is and what next action that specific situation implies or requires, the result of which then leads to the decided-upon action which can, though, be revised if new information arises (Image 1).

Image 1. Illustration of the decision-making process in sudden, time-critical situations. (Kamunen et al., 2022)

In this paper, we will show how the overall joint activity of patrolling can be halted or slowed down when the progressivity of a single sequence is compromised during one or more of these steps, due to a missing or delayed second-pair part. Additionally, we will discuss the underlying (in)actions that potentially inform such trouble, as well as the participants' methods for overcoming them.

3. Data and Methods

The primary data for this paper consist of video recordings collected in a UN military observer course (Rautiainen et al., 2021). UN military observers (UNMOs) are unarmed soldiers, usually officers, whose task is to support peacekeeping operations by patrolling conflict areas and making observations on possible violations of peace agreements, as well as conducting investigations and negotiations between different parties. The course is a two-and-a-half-week general-level course that trains the basic skills needed for working as a military observer and prepares the course trainees for taking part in international missions. We focus specifically on one two-person team1 in a car-patrolling exercise, taking place over the course of one day at the end of the course. During this exercise, the team patrols a simulated conflict area in a car and encounters various simulated incidents. They use English as their working language and lingua franca, and neither of the team members speak English as their first language. At the time of data collection, face masks were regularly used, and their use is recognised as a possibly interfering factor when it comes to hearing or seeing facial expressions. However, as the masks are not topicalised by the participants, they are not highlighted in the analyses. The video data was collected with two GoPro cameras attached to the dashboard, one recording the events in front of the car and the other capturing the (inter)actions of the trainees inside the vehicle. High-quality audio from inside the car was captured with a four-directional microphone attached to the elbow rest in the centre of the car. In total, the duration of the video materials analysed for this study is eight hours, from which 13 instances were identified where a response was treated as insufficient or missing, evidenced by pursuits of responses by the speaker of the first-pair part. The team members have given their informed consent for using the data in research and related publications. All signs that might reveal their identity, rank, or country of origin have been changed or removed from the transcriptions and screen captures to pseudonymise the participants.

In the exercise, the teams move and operate as a vehicular unit (Goffman, 1971), in which the trainees have different and specific tasks and responsibilities connected with their roles, which they allocate between themselves prior to patrolling. The team leader, who typically sits in the front passenger seat, is responsible for navigating (using a physical map and a GPS device) and radio communication with the net control station (NCS). The team leader also has the right to make decisions for the team. The driver's main task is to drive the patrol vehicle according to the team leader's navigational instructions, as the team leader is the one with better access to the navigational devices and the planned route. Both team members are responsible for conducting the observation tasks and monitoring the surroundings for potential threats or violations. If they see any troops or weapons systems that should not be in the area according to the cease-fire agreement, they should both confirm the observation and fill in and, in some cases, send a situation report through the radio. While usually the team members should switch their roles during the exercise, in this team, the roles and responsibilities remain the same throughout, due to a possible misunderstanding of the exercise briefing. In this specific team, the team leader not only has the deontic authority that comes with their assigned role but also the epistemic authority as someone who both participants treat as having more experience on the type of work they are rehearsing. Thus, it is usually the driver who seeks the team leader's confirmation for and acceptance of potential next actions.

In our analysis, we rely on the concepts and principles of ethnomethodological conversation analysis (EMCA, Garfinkel, 1967; Sidnell & Stivers, 2013; see also Eilittä et al., 2023). The sequential analyses are supported by ethnographic observations and field notes and the researchers' first-hand knowledge and experiences regarding exercise, the patrol route, and the various taskings (see Kamunen et al., 2023). The participants' talk and embodied conduct have been transcribed using Jeffersonian (Jefferson, 2004; Hepburn and Bolden, 2017) and Mondadian (Mondada, 2018) conventions, respectively, and the transcripts are complemented with comic-strip illustrations of the excerpts (e.g., Laurier, 2019; Laurier & Back, 2023) with approximations of the movement and the position of the car depicted as a bird's-eye-view illustration next to the comic strips, when relevant.

The focal phenomenon was identified through unmotivated viewing of the data. The inductive approach in CA (ten Have, 2007; see also Kamunen et al., 2023) to identifying research topics entails identification of specific practices, that is, turn design features, that have a distinctive character, specific location (within a turn or sequence), and has distinctive outcomes for the meaning of the action (Heritage, 2010, p. 212). Here, though, what initially stood out in the data was the recurring absence of responses where responses would have been expected, such as after direct questions, requests for instruction, and so on, which appeared to be a feature unique to this one team. A collection was formed of such instances (n=13), and after their initial analyses, those missing responses revealed to be markers for some interactional trouble between the participants regarding their concurrent personal projects. Of the 13 cases altogether, four were chosen to illustrate the analyses in this paper for their representativeness of the types of miscommunication, caused by either the participants' different understandings of and orientations to the same situation (n=3) or different temporal prioritisation of lines of action (n=10).

4. Missing Responses as Markers of Interactional Trouble

In this section, we analyse four excerpts where a first-pair part is produced that does not receive a relevant second-pair part in due time. First, in subsection 4.1 we look at a case where a response is delayed due to the recipient's prioritisation of his own ongoing line of action. Second, in subsection 4.2 we analyse two cases of divergent understandings regarding the phase or the on-goingness of the decision-making process, which becomes visible in the interaction through missing or non-type-fitting responses. Finally, in subsection 4.3, we will investigate a case where a response is initially missing in the context of diverging prioritisations of activities, but that due to the eventual verbalisation of said priorities does not lead to any hindrance in the team's joint action. In the analyses, we show the participants' sense-making processes regarding the situation and their ways of progressing the team's joint activity, which include pursuits of a response through repetitions and reformulations of the first-pair part, as well as (attempts at) solving the other participant's ongoing, prioritised project, and doing anticipatory or preparatory moves while waiting for the other to be available.

4.1 Diverging temporal prioritisations of task-specific projects

The first example represents a case where the driver (DRV) asks the team leader (TL) for navigational instructions, and the response is delayed and treated as missing by the speaker of the first-pair part due to the recipient's involvement in – and prioritisation of – their own ongoing line of action. Here, the team drives to an intersection where the road straight ahead is blocked by a minefield, marked by yellow mine tape on both sides of the road. There are two next actions that are expected in such situations: 1) checking if the minefield is a previously known one and warning other teams if it is not, and 2) finding a safe route around it. In this example, TL prioritises the first line of action while DRV prioritises the second one, but they do not communicate these prioritisations to each other. Prior to the excerpt, the team has inspected a military position and have been discussing whether all the weaponry there is allowed according to the cease-fire agreement while driving along the planned patrol route towards their next tasking point. The excerpt starts with DRV browsing the aide memoir2 (AM in the transcripts) to check the maximum calibre of weapons that are allowed to be stored in the position, and he reads the part out loud to TL. TL then repeats the calibre back to DRV and grabs the aide memoir (l. 4) to check for himself.

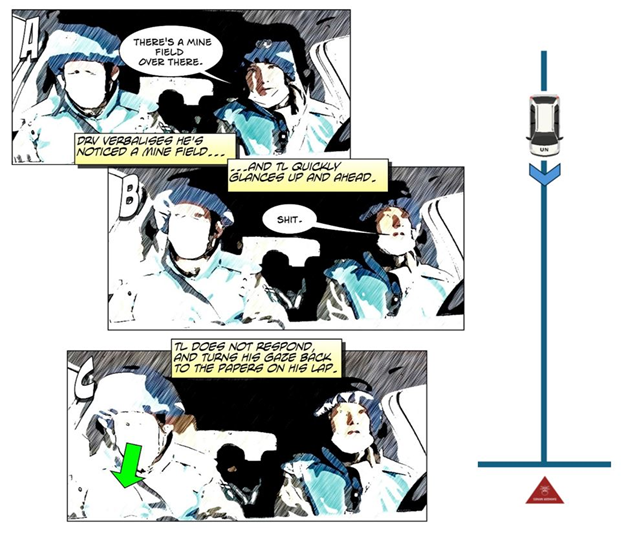

Extract 1. A minefield

Open in a separate windowFigure 1_1. DRV produces a noticing of the minefield

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

In line 8, DRV voices a noticing of the minefield ahead, evaluates the situation negatively (l. 13) and slows down, but keeps driving forward. As shown by Haddington and colleagues (2022), such noticings often mark transitions from ongoing activity to more active, task-specific monitoring, as certain noticeable features in the environment (troops, weapon systems, minefields) imply specific next actions to be taken.3 TL lifts his gaze and looks forward for a moment, but then lowers his gaze back down, producing no uptake or acknowledgement of the noticing (figs. 1B-C). In line 22, TL looks up from the paper again and towards the intersection, produces a quiet "okay", and then continues reading. After another long silence, he concludes the previous topic by stating that the weapons they saw did not violate the peace agreement. DRV acknowledges this (l. 29), drives a little bit forward and then stops the car. He then points towards the intersection with his right-hand index finger and repeats his noticing (l. 36), also verbalising the effect of the noticed thing on the course of the drive – they cannot go through – making this a noticing done "for driving" (Keisanen, 2012, p. 206) rather than a noticing done for observing. As the original noticing did not initiate any new next action, the rephrased noticing is now, by its design, more explicitly a report of trouble, which occasions provision of assistance from the recipient (Kendrick & Drew, 2016; Kendrick, 2021) which, in the case where DRV has the control over the car, would relevantly be advice or instruction. The reformulation also reveals DRV's treatment of TL's turns as insufficient as a response to the original noticing.

Figure 1_2. DRV pursues response by repeating the noticing

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

TL begins to look for something inside the car and turns around reach to the backseat (fig. 1H). His turn in line 41 ("where is this,") can be heard either as searching for an item or as self-talk regarding the team's location, as the next relevant thing in this situation would be to get the exact location of the minefield to be either confirmed or informed about. DRV treats the turn as the former and asks what TL needs (l. 43). TL grabs and brings to his lap a folder, stating that they need to keep a logbook as well (l. 46). This indicates that TL is orienting to the minefield as a known one and is preparing to make a note of it still being there, as they have been instructed. DRV, on the other hand, treats the minefield's effect on their mobility as a more urgent matter and pursues the topic by asking TL what their next action should be and stating they have to turn around. TL responds to the question by stating they have to inform the NCS about the minefield, but DRV treats this, too, as an insufficient response and continues to prompt his own project by ignoring TL's statement and instead voicing options for where they can drive (ll. 55-58), for TL to either accept or reject.

Figure 1_3. DRV explicates his problem to mobilise a relevant response

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

Figure 1_4. DRV offers candidate solutions for the problem

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

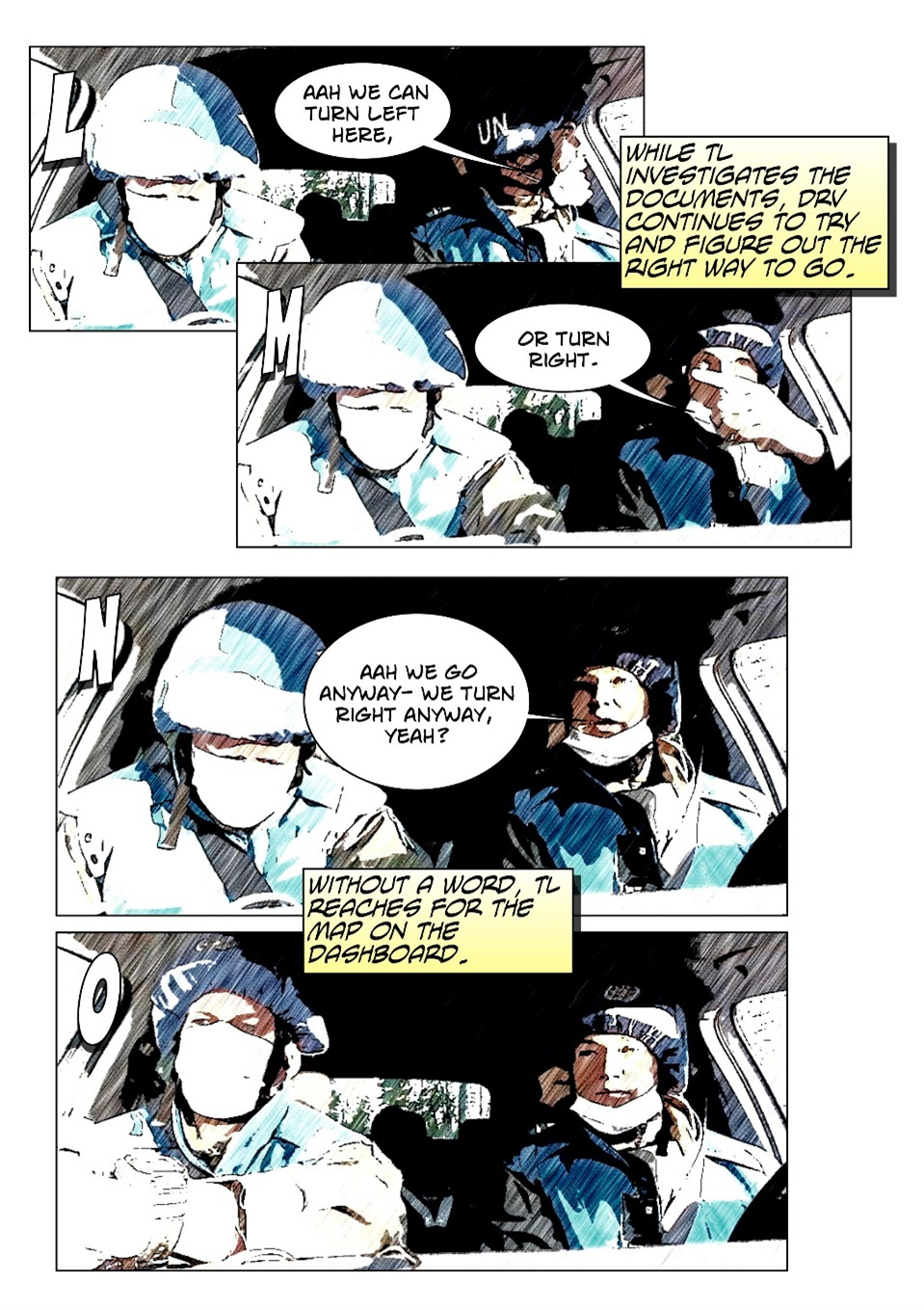

Again, there is no uptake from TL, resulting in another silence. DRV produces a grunting noise, possibly hearable as frustration and, after another silence, works to progress the situation by verbalising his noticing that they are supposed to continue to the right in any case (l. 64), asking TL for confirmation with a turn-final 'yeah?'. TL picks up the map and holds it in DRV's view (fig. 1P), showing him their current location and states they are going to the right (ll. 69-72), which DRV acknowledges and slowly begins to drive towards the intersection and prepares to turn to the right, treating the navigational trouble now as resolved.

Figure 1_5. TL shows DRV the map and instructs him where to drive

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

In this excerpt, there is observable misalignment in the participants' orientation to the temporal prioritisation of different lines of action. For DRV, who is responsible for controlling the car and its movement, the issue of the road seemingly being blocked is prioritized. TL is the person responsible for reading the map and is treated here by DRV as the one who can, and should, give him instructions on how and where to proceed. In this light, DRV's turns in lines 8 and 36 can be treated as not just informing statements but as noticings that carry implications on future action (Haddington et al., 2022), and thus as something that requires TL's contribution. DRV yet orients to TL's ongoing project with the previous tasking regarding the inspection and does not pursue a response until after it has been concluded in line 30. The stopping of the vehicle is a concrete action to communicate not being able to continue and is done concurrently with the repetition of the noticing. Line 49 is an explicit request for information regarding what to do next, but whereas DRV appears to mean "where to drive next", TL treats the situation not as a navigational trouble but as an observation task and responds by reporting the next action he will take. After another "failure" in getting the sought-after answer out of TL, DRV begins to look for a solution to the situation himself (ll. 55-58), but still seeks confirmation for the decision-making from TL (l. 64). TL then, as a response to his question or not, provides DRV with the information he was seeking (l. 72), and the matter is resolved. The interactional trouble thus stems from two instances of misalignment: first, orientations to and temporal prioritisations of different projects and, second, different orientations to the same noticing and its treatment either as a mobility issue or an observing issue, respectively.

4.2 Diverging understandings of what has already been decided

The next two examples are of cases where there appears to be different understandings between the participants regarding what information has already been given and which projects are currently underway. In Excerpt 2, we will again observe TL seemingly ignoring DRV's requests for direction. Here, though, the requested directions have already been verbalised by TL (line 1), who has then moved on to his own project of comparing pictures of weapons systems in his aide memoir to ones they have previously encountered. At the beginning of the excerpt, the team arrives at an intersection with multiple directions to be taken. There is a wooden barrier on the road leading straight forward and a series of signs on the trees indicate the correct way to proceed, which is to the left. While driving, DRV is also leafing his aide memoir in search of the type for the howitzers they just observed. In the transcripts, talk on the radio by NCS (call sign Hotel) that is not directed to the focal team is labelled as RAD and transcribed in italics.

Extract 2. Which direction?

Open in a separate windowIn line 1, TL gives navigational instructions to DRV in reference to the signs, "we need to follow over there." DRV lifts his gaze from the aide memoir, produces a grunting sound (line 6), and then starts to sweep the surroundings with his gaze, turning his head left and right, visibly doing searching (figs. 2B-E). As he begins to steer the car to the left, he asks TL which direction they should go (line 14).

Figure 2_1. TL verbalises the direction where the team should head, DRV displays uncertainty of the referent

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

Figure 2_2. DRV asks TL where they should go, TL reads his aide memoir and does not respond

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

TL does not respond to nor acknowledge DRV's question in any way and turns to gaze at his aide memoir in line 21 (fig. 2G). During DRV's turn, another team can be heard talking to the NCS on the radio (lines 15 and 20), but the volume is not loud enough to drown any talk within the car cabin. DRV keeps the car moving, turns his gaze down to the aide memoir again (fig. 2H) and leafs it for a moment.

He then indicates a change of state and having found what he was looking for in line 26 ("ah, here") and turns the booklet to his right for TL to see (fig. 2I). DRV states that what they saw was Greyland troops4, and TL turns to look at the page (fig. 2H). He begins to produce a partially disaffiliative turn "yeah but what is-", which gets cut off as DRV self-selects in interjacent overlap (i.e., with no projectable TRP in sight, see Jefferson [1986]) and interrupts TL by repeating his original question regarding where he should drive (line 36). The question is slightly reformulated: it starts with "so", indicating that a previous topic/action has been concluded, and it ends with "now", communicating the uncertainty of where exactly to continue and, possibly, the urgency of getting the information, as the time window for making the decision is getting smaller by the second due to DRV's decision to not stop the car. DRV also produces a candidate answer to his own inquiry ("this one?", line 39), in effect transforming it into a polar question. Instead of answering directly, TL points to forward left (fig. 2L) and merely verbalises the existence of the sign indicating the correct road. DRV quickly adjusts the car's direction and drives on the indicated route, thus treating the response as sufficient.

Figure 2_3. DRV attempts to aide TL to finish his project in order to get a response

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

In the excerpt, we could again observe the participants' engagement in, and prioritisation of, different projects. As Goodwin and Goodwin (2012) note, talk about details of driving takes priority over other talk as it is intertwined with local tasks entailed in driving, and can thus interrupt other conversation in progress (p. 206). Whereas TL is visibly orienting to filling out a patrolling document, DRV is in need of more specific navigational advice. For DRV, the situation is time sensitive as he keeps the car in motion, and thus the requested information regarding the right direction is increasingly urgent. We cannot say for certain whether TL's failure to produce a response is due to his focus on his own task-at-hand, or because TL possibly treats DRV's question as redundant as the direction is clearly indicated by the signs and thus accessible for everyone. DRV nevertheless appears to orient to TL's prioritisation of filling the report by attempting to help locate the information TL is possibly searching for. In sum, DRV not only prompts a response by repeating and reformulating his request for information but also accommodates his own action to 'solve' TL's ongoing, prioritised activity in order for him to be able to attend to DRV's navigational trouble and give advice regarding the right way, instead.

In the third excerpt, the team has just driven past artillery positions that are not – according to the cease-fire agreement – allowed in the area. They have both previously, upon first noticing the positions, verbalised that the situation is a reportable violation, but different understandings and miscommunication regarding when to do the reporting create confusion for the DRV on what they will do next. Just prior to the excerpt, the team has made observations on the troops and weapons systems and tried to talk with the soldiers5 who have not been cooperative and have told them to leave the area. DRV has stopped the car right after the artillery positions with the intent to start filling in a situation report on what they have agreed is a violation, but TL instructs DRV to get moving as one of the soldiers who told them to leave is approaching the car.

Extract 3. Four howitzers

Open in a separate windowFigure 3_1. DRV expresses uncertainty regarding the reporting procedure

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

After TL's directive (l. 1), DRV displays some resistance but nevertheless starts slowly driving forward. DRV's unfinished turn is followed by a pause of 1.1 seconds, after which DRV produces an understanding check about whether the existence of the artillery weapons in the area is a violation of the peace agreement. TL displays strong agreement with an extreme case formulation "this is definitely a viol-", which he then cuts off to tell DRV to close the side window.

Figure 3_2. DRV produces a candidate understanding, which TL does not confirm nor decline

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

DRV then produces a candidate understanding "so we don't report this?" in line 24, which contravenes TL's statement of the situation being a violation, and thus bears the implication of reporting it. TL responds with a non-type-conforming turn; he does not directly confirm nor correct the candidate understanding but instead refers back to what one of the course instructors had told them about not making rushed decisions (ll. 29-33), and then verbalises what he thinks they should do next: they have seen these specific weapons in an area where there should be none, which counts as a violation and is thus a matter that requires the filling out and sending a situation report, and the first step in this process is asking the net-control station for a logging time to put into the report (ll. 38-48).

Figure 3_3. TL verbalises their observations and the relevant next step

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

Figure 3_4. DRV repeats his question and backs it up with a reference to a previous exercise

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

Although TL does not mention the word "report" explicitly, both the statement that they have witnessed a violation and the mention of asking for a logging time imply the immediate next action of both writing and sending out a report. DRV does not seem to be on the same page with TL, as he treats TL's response as insufficient and pursues an answer to his question about whether or not they should report what they saw with a reformulation of the previous question (l. 54). DRV's question is followed by almost 12 seconds of silence, during which TL keeps sweeping the foreground with his gaze. In line 61, DRV tries a different approach by referring back to a similar case from the previous day, pursuing a (positive) response to his question regarding the action of reporting.

Figure 3_5. TL produces the answer DRV was looking for

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

After DRV's question, TL lets out a sigh and begins to explain the situation in more detail, seemingly orienting to the fact that there is no hurry with the reporting as the howitzers are not in readiness to shoot and thus do not pose an immediate danger to anyone. Nevertheless, he states that they should do a situation report because they are dealing with a violation (ll. 72-74), putting emphasis on the word 'violation'. DRV acknowledges and accepts TL's answer and then initiates the reporting process by offering to ask for a logging time through the radio.

In this excerpt, the misalignment is not caused by the participants' orientation to different lines of action, but rather by their different approaches to the due process and relevant timing of the next action: DRV is orienting to the question of whether or not they should send a report about the violation, whereas for TL, who treats the matter as already decided, the question is when to send the report. TL's turns throughout the excerpt make visible his sense-making process and show that he treats the situation as a violation which, to him, automatically means that a report should be sent (see Haddington et al., 2022). He has also made, and verbalised, observations on the weapons' readiness to fire and has come to the conclusion that they are not in a hurry to warn others yet. Additionally, he also orients to the fact that they have been told by the role-playing soldier to leave the area. For DRV, the process does not seem to be as clear, as he does not pick up the implications of what TL says but keeps treating his responses as insufficient, until it is explicitly verbalised by TL that they will, indeed, send out a report.

In the cases presented in this section, the missing responses and their repeated elicitation attempts mark misalignment in how the participants perceive and – crucially – communicate their sense-making processes to each other, leading to their treatment of the issue as solved by one participant and still underway by the other. A retrospective view provided by the analyses shows how both DRV and TL go through their own, diverging, prioritised processes regarding the nature of the situation and the relevant immediate next action, but fail to recognise each other's positions, which in both cases leads to drawn-out sequences that hinder the progress of forming a joint decision.

4.3 Shared temporal prioritisations: beginning to act while waiting for instructions

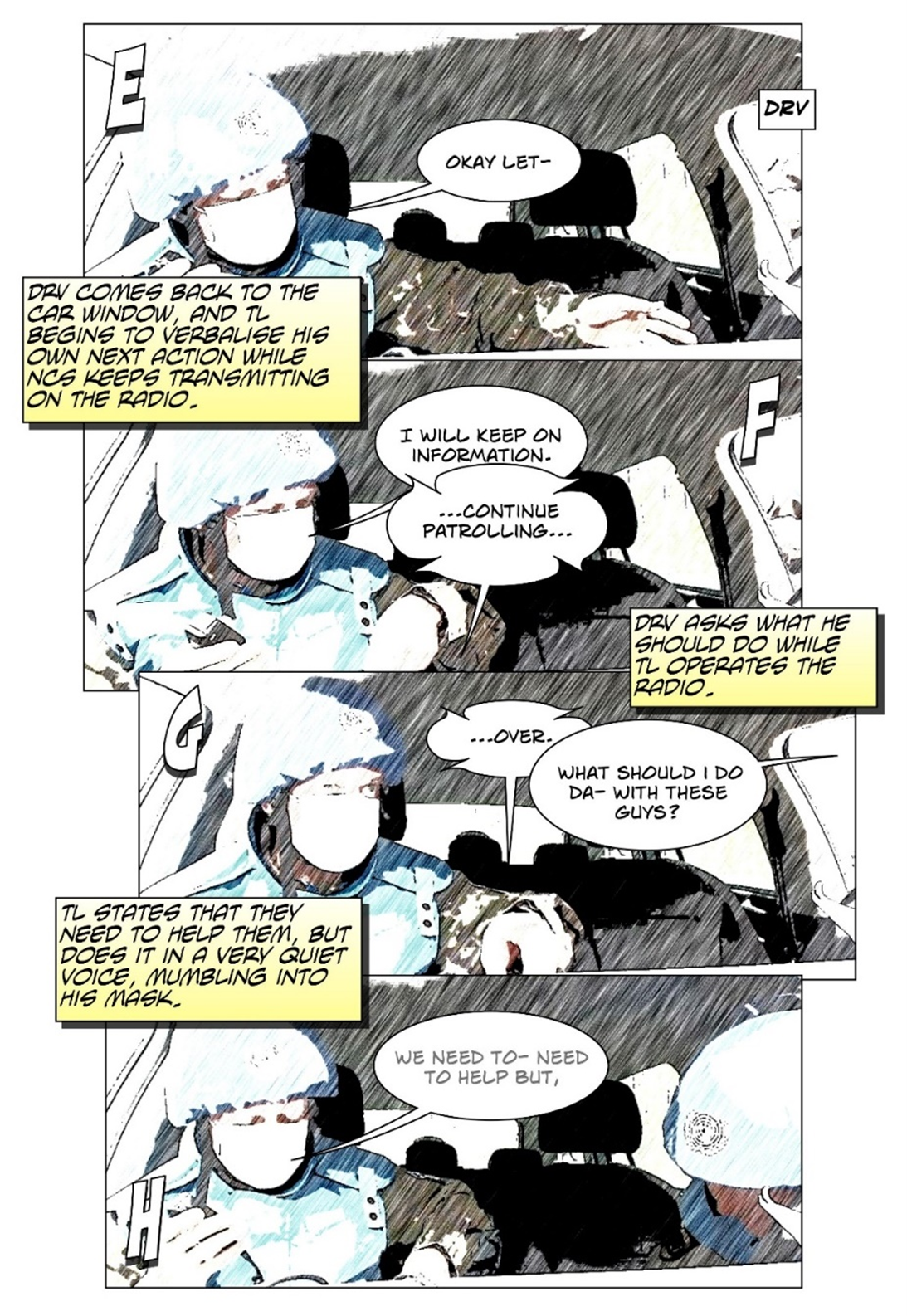

The final excerpt is from the afternoon, towards the end of the exercise, and represents a situation where the verbalisation and the shared recognition of the action hierarchy appear to have a mitigating effect on the consequences of a missing response towards the progressivity of the team's action. The missing response nevertheless affects the progressivity of the interaction and the giving of instructions. The team has arrived at a tasking point and encountered two UN soldiers, one of whom seems to be badly injured and the other one outwardly fine but passive. DRV has stopped the car, and they are trying to figure out what has happened. After trying, in vain, to address the soldiers from inside the car, TL has told DRV to get out of the car and try to ask what has happened while he will report to the NCS that they are stationary at their current location. The excerpt begins when DRV has just moments ago stepped out of the car, and TL has stayed inside, holding the radio handpiece and waiting for a possibility to transmit. The channel is occupied by another team that is discussing with the NCS. In the transcripts, talk on the radio not directed to the focal team is labelled as RAD, and when directed to the focal team, as NCS.

Extract 4. Injured UN soldiers

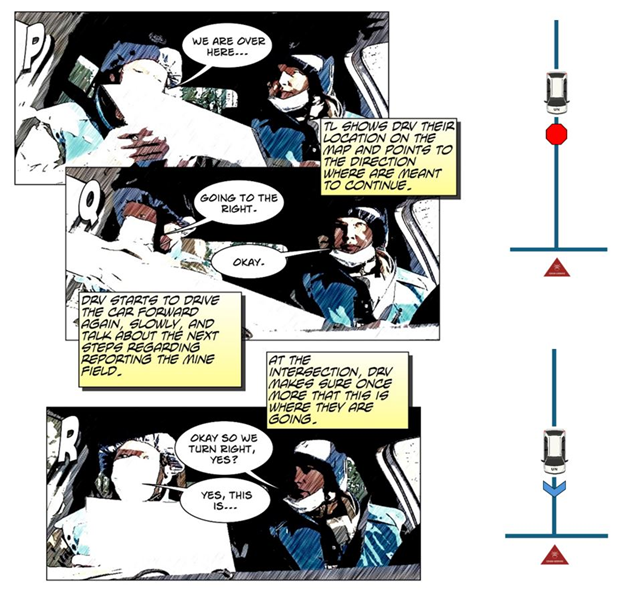

Open in a separate windowIn line 1, DRV comes back to the car door and asks TL whether they will go or not, possibly assuming that TL has already managed to send their location to NCS. TL does not respond but observably leans towards and manipulates the controls of the radio (fig. 4A), where the other team can be heard talking. DRV then moves to act on his own, walks to the back of the car and recovers the first aid bag from the boot (fig. 4B). Throughout lines 7 to 35, TL listens to the radio traffic and waits for an opening for his own transmission, while DRV tries to get information from the soldiers at the scene.

Figure 4_1. DRV recognises TL's orientation to the radio and proceeds to prepare for future action

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

In line 35, DRV has moved back closer to the car door and peeks through the window. TL turns to look at DRV (fig. 4E) and, treating his own (in)action at this point accountable, begins a turn in line 38 which he cuts off and abandons, and continues to verbalise his own conduct, "I will I will keep on information." TL uses the first-person singular pronoun "I", excluding DRV from this activity, and a tense that leaves the duration of his own activity indefinite. TL looks at the scene and points to it, possibly in preparation to say something (fig. 4G), when DRV asks in line 43 what he should do, also using the first-person singular pronoun and displaying orientation to this division of activities. TL responds in line 49 but speaks quietly and leaves his turn unfinished. DRV either does not hear TL or treats the response otherwise insufficient, and he pursues a response by repeating his question in line 53. Immediately after DRV's pursuit, TL takes advantage of the free radio channel and begins to transmit a message (figs. 4I-J). DRV recognises TL's activity, orients to it as a prioritisable one, and produces no further pursuits. Instead, he again begins to act on his own and leaves TL to operate the radio. It is likely that DRV can hear the radio also outside of the car, and soon after TL has finished his message and NCS has acknowledged it and read it back, DRV gestures to TL to join him outside (figure 4L), which TL does.

Figure 4_2. TL verbalises his actions while listening to the radio traffic, DRV asks for instructions

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

Figure 4_3. DRV repeats his question, but moves on to act on his own while TL sends a radio message

Open in a separate window

Open in a separate window

In this excerpt, we can see a difference in DRV's orientation to eliciting a response in comparison to the earlier excerpts. Here, there appears to be a clear division of tasks between the team members: TL operates the radio and, in the meanwhile, DRV's task is to get more information on what has occurred. While DRV seeks help in his decision-making regarding what to do next as a team, he nevertheless recognises TL's involvement in operating the radio, which is also jointly understood as a prioritisable line of action at this point. What becomes observable here is DRV's orientation to progressing the team's joint activity whether or not TL is able to respond and give orders or instructions on how to proceed. In contrast to the previous cases, this task also requires actions outside the car, and thus the vehicular unit (Goffman, 1971) is broken down into two individual agents whose actions are not necessarily dependent on the other party. Possibly because of these factors, DRV does not put as much effort into eliciting a response from TL. He lets the missing response to his first question pass, and repeats the second question once, after which he begins to act independently while waiting for TL to be done with the radio – and thus to be able to give instructions regarding what to do next – and retrieves the first aid kit in preparation for potential future medical assistance. Another possible factor here is the shared understanding of the priority of sending the radio message: it is important that TL will be able to transmit immediately when the channel becomes free.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

In this paper, we have investigated instances where a relevant response to a direct question is either left unanswered by the recipient of the question or where it is treated as irrelevant or insufficient by the first speaker. The study is situated in a context where the participants encounter situations that they have not been initially aware of and have to deal with in the moment, such as coming across previously unknown military troops or positions, minefields, and blocked roads or detours. In such moments, the team needs to make sense of what the situation is and decide together what action is required from them. This phenomenon is strongly tied to the wider situated activity of patrolling and observing and includes different stakes for the different participants. Within the exercise context – and with respect to the roles that come with it, as instructed during the course – the driver is expected to be told how and where to drive by the team leader who is responsible for navigation, and thus, the expectation and relevance of a timely produced response is even higher than in some other collaborative situations. Similarly, even though the team is expected to make decisions regarding their observations and the reporting thereof together, the team leader is ultimately responsible for and has authority over the team's actions and, in the case of this specific team, is also treated as more experienced than the driver.

The paper set out to answer the following questions: How does a missing or delayed response affect the team's decision-making; what the participants' methods are for dealing with a missing or delayed response, and what, if anything, missing or delayed responses can reveal about the overall interactional dynamics within a team. A missing or delayed second-pair part was shown to affect the interactional process of decision-making mostly regarding the fluidity of the process. In situations where a team member's input is required and, consequently, requested for a decision regarding a next line of action, a lack of a response was treated as problematic, but did not necessarily lead to any major hindrance or setbacks to the wider task of patrolling due to the work done by the speaker of the first-pair part. What was slowed down, though, was the achievement of a shared understanding regarding the next line of action, with the exception of situations where the decision-making concerns navigational issues and the driver does not continue driving until receiving instruction on where to go.

The solutions for eliciting a response were designed in and for each respective situation and included methods such as pursuits, repetitions, and reformulations. In the first excerpt, also the movement of the car was utilised as a resource for communicating DRV's problem of not knowing where to continue and further underlined with the repetition and reformulation of the noticing and its consequences for the team. The speaker of the first-pair part was also shown to be sensitive to the recipient's perceived actions in their elicitation of a response. In some of the cases in the collection, the first speaker would just wait until the other's prioritised action was complete and only then began to pursue a response (cf. the beginning of Ex.1). In Excerpt 2, DRV not only prompted a response by repeating and reformulating his request for information but also worked to 'solve' TL's ongoing, prioritised project in order for him to be able to attend to DRV's more time-critical problem, instead. In the third excerpt, on the other hand, DRV displayed a recognition and orientation to a potential communication problem by producing reformulations and understanding checks until a sufficient answer was given. Finally, Excerpt 4 presented a situation that was different in the sense that the team was not moving, and the task required action outside the vehicle, so DRV could also begin to act independently to progress the team's joint activity while TL was visibly occupied with the prioritised activity of monitoring and handling the radio.

Studying moments where a response was noticeably missing revealed different kinds of interactional trouble between the participants. What could be observed in all the cases was some form of mis-/noncommunication regarding differing ways of either perceiving or structuring their respective projects. The missing responses are thus not the cause of sequential interactional trouble, but rather an indicator of more profound problems ('interactional warning sign', see Nevile, 2013) in the team's achievement and management of shared understanding regarding their next action as a team, as well as of their own mutual interactional awareness. For instance, as was the case in Excerpts 2 and 3, TL treated some matters as already solved or brought to conclusion, and did not recognise that for DRV they might still appear unclear or underway. This then potentially led to the situations we observed, such as in Excerpt 3, where a polar question was responded to with long explanations of TL's reasoning of the situation, rather than with a direct answer that would have been type-conforming to the sincere question DRV was asking.

This study contributes to earlier research on missing responses and decision-making, as well as interaction in simulated training contexts (e.g., Hindmarsh et al., 2014; Koskela & Palukka, 2011). The study also sheds light on how participants manage interactional troubles in complex, often mobile situations that emerge suddenly and require sense-making and problem solving. As the analysed excerpts showed, there are a variety of ways to handle situations of interactional trouble, and the troubles, as well as their handling, are strongly situated and contextual. Methodologically, the study also represents a new (to the authors' best knowledge) and interesting form of inductivity with the process of identifying a research topic from the data. What originally caught the analysts' eye and was the basis on which a collection was formed – a missing response – proved not to be so much the main focus of the study but more just a common denominator in the cases, and an indicator for the interactional misalignment that eventually took centre stage in the analyses.

Finally, the identification of such an indicator also creates possibilities for practical applicability: the findings can be used in training to highlight the significance of interaction in and as part of decision-making and team communication more widely, as well as presenting missing responses to questions or noticings as an interactional warning sign that can also be observed and, consequently, intervened with in real-life situations. While the research was conducted in a training context, the same 'rules' and features of social interaction nevertheless apply in real life, and the examples of various interactional trouble identified in the study can thus also be relevant in other contexts than training events or simulations. For example, Excerpt 3 of this paper has already been successfully used in interaction awareness workshops on later iterations of the military observer course as an example of potential communication problems within patrol teams and for reflection tasks regarding aspects of interactional competence. The workshops have elicited active conversation and received good feedback from both the trainees and the instructors, as well as underlined the importance of applied, qualitative interaction research in the military context, and consequently in and for other professional settings, as well.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the course participants, especially the trainees and the instructors, for letting us get a glimpse of their important and valuable work, as well as FINCENT and the Finnish National Defense University for their help and support. We are also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback and comments on an earlier version of this paper. This research was funded by the Finnish Research Council (project number 322199), the Eudaimonia Institute at the University of Oulu, and the Finnish Cultural Foundation.

References

Amar, C., Nanbu, Z., & Greer, T. (2021). Proffering absurd candidate formulations in the pursuit of progressivity. Classroom Discourse, 13(3), 264-292. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2020.1798259

Atkinson, J. Maxwell, & Heritage, John (1984) (Eds.). Structures of social action: Studies in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge University Press.

Bolden, G. B., Mandelbaum, J., & Wilkinson, S. (2012). Pursuing a response by repairing an indexical reference. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 45(2), 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.673380

Eilittä, T., Haddington, P., Kamunen, A., Kohonen-Aho, L., Oittinen, T., Rautiainen, I., & Vatanen, A. (2023). Ethnomethodological conversation analysis in motion: An introduction. In Haddington, P., Eilittä, T., Kamunen, A., Kohonen-Aho, L., Oittinen, T., Rautiainen, I. & Vatanen, A. (Eds.) Ethnomethodological Conversation Analysis in Motion: Emerging Methods and New Technologies (pp. 1–18). Routledge.

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology. Prentice-Hall.

Goffman, E. (1971). Relations in public: Microstudies of the public order. Basic Books.

Goodwin, M. H. & Goodwin, C. (1986). Gesture and coparticipation in the activity of searching for a word. Semiotica, 62(1-2), 51–76. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1986.62.1-2.51.

Goodwin, M. H., & Goodwin, C. (2012). Car talk: Integrating texts, bodies, and changing landscapes. Semiotica, 2012(191), 257-286.

Haddington, P., Keisanen, T., Mondada, L., & Nevile, M. (Eds.) (2014). Multiactivity in social interaction: Beyond multitasking. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Haddington, P., Kamunen, A. and Rautiainen, I. (2022) Noticing, monitoring and observing: Interactional grounds for joint and emergent seeing in UN military observer training, Journal of Pragmatics. 200: 119–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2022.06.005

Have, P. t. (2007). Doing conversation analysis: A practical guide. 2nd edition. Sage.

Hepburn, A., & Bolden, G.B. (2017). Transcribing for Social Research. Sage.

Heritage, J. (2007). Intersubjectivity and progressivity in person (and place) reference. In T. Stivers & N. J. Enfield (Eds.), Person Reference in Interaction: Linguistic, Cultural and Social Perspectives (pp. 255–280). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511486746.012.

Heritage, J. (2010). Conversation analysis: Practices and methods. In D. Silverman (Ed.), Qualitative Sociology: Theory, Method and Practice (3rd ed.) (pp. 208–230). Sage.

Hindmarsh, J., Hyland, L., & Banerjee, A. (2014). Work to make simulation work: 'Realism', instructional correction and the body in training. Discourse Studies 16(2). 247–269.

Jefferson, G. (1981). The abominable ne? An exploration of post-response pursuit of response. In P. Shroder (Ed.), Sprache der gegenwaart [Contemporary Speech] (pp. 53–88). Pedagogischer Verlag Schwann.

Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In Lerner. G. (Ed.) Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 13–31). John Benjamins.

Kamunen, A., Haddington, P., & Rautiainen, I. (2022). "It seems to be some kind of an accident": Perception and team decision-making in time critical situations. Journal of Pragmatics. 195: 7–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2022.04.001

Kamunen, A., Oittinen, T., Rautiainen, I., & Haddington, P. (2023). Inductive approach in EMCA: The role of accumulated ethnographic knowledge and video-based observations in studying military crisis management training. In Haddington, P., Ellittä, T., Kamunen, A., Kohonen-Aho, L., Oittinen, T., Rautiainen, I., & Vatanen, A. (Eds.), Ethnomethodological Conversation Analysis in Motion: Emerging Methods and New Technologies (pp. 153-170). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003424888-11

Keisanen, T. (2012). "Uh-oh, we were going there": Environmentally occasioned noticings of trouble in in-car interaction. Semiotica, 2012(191), 197–222.

Kendrick, K. H. (2021). The 'Other' side of recruitment: Methods of assistance in social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 178, 68–82.

Kendrick, K. H., & Drew, P. (2016). Recruitment: Offers, requests, and the organization of assistance in interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 49(1), 1–19.

Kent, A., & Kendrick, K. H. (2016). Imperative directives: Orientations to accountability. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 49(3), 272–288.

Koskela, I., & Palukka, H. (2011). Trainer interventions as instructional strategies in air traffic control training. Journal of Workplace Learning 23(5). 293–314.

Lerner, G. H. (2004). On the place of linguistic resources in the organization of talk-in-interaction: Grammar as action in prompting a speaker to elaborate. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 37, 154–184.

Laurier, E. (2019). The panel show: Further experiments with graphic transcripts and vignettes. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 2(1), 10.7146/si.v2i1.113968.

Laurier, E., & Back, T. B. (2023) Recurrent problems and recent experiments in transcribing video: Live transcribing in data sessions and depicting perspective. In Haddington, P., Eilittä, T., Kamunen, A., Kohonen-Aho, L., Oittinen, T., Rautiainen, I. & Vatanen, A. (Eds.) Ethnomethodological Conversation Analysis in Motion: Emerging Methods and New Technologies (pp. 245–264). Routledge.

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: challenges for transcribing multimodality, Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85–106.

Nevile, M. (2013). Collaboration in crisis: Pursuing perception through multiple descriptions. In A De Rycker & Z Mohd Don (Eds.), Discourse and crisis: Critical perspectives (pp. 159–183). John Benjamins Publishing.

Pomerantz, A. (1984). Pursuing a response. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action (pp. 152–164). Cambridge University Press.

Rautiainen, I., Haddington, P., Kamunen, A., & Oittinen, T. (2021). PeaceTalk Video Corpus pt. 2 (Military Observer Course). University of Oulu. http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:att:5b7d670d-4680-4831-b72d-a70bae7c1488

Rautiainen, I. (2022). Practices of promoting and progressing multinational collaborative work: Interaction in UN military observer training [Doctoral Dissertation]. University of Oulu. http://urn.fi/urn:isbn:9789526235035.

Sacks, H. S., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696-735.

Schegloff, E. A. (1968). Sequencing in conversational openings. American Anthropologist, 70, 1075–1095.

Schegloff, E. A. (1979). The relevance of repair to syntax-for-conversation. In Discourse and syntax (pp. 261-286). Brill.

Schegloff, E.A. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction: A primer in conversation analysis. Cambridge University Press.

Sidnell, J. (2010). Conversation analysis: An introduction. Wiley.

Sidnell, J., & Stivers, T. (2013). The handbook of conversation analysis. Wiley-Blackwell.

Stivers, T., & Robinson, J. D. (2006). A preference for progressivity in interaction. Language in society, 35(3), 367–392.

Stivers, T., & Rossano, F. (2010). Mobilizing response. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 43(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810903471258

1 Altogether four teams were recorded during this exercise, but the recurring absence of responses was present with only the team analysed in this paper.↩

2 The aide memoir is a booklet that has been handed out to all the trainees and contains all the necessary information regarding the operation, including images and designations of all the different weapons systems used by the parties of the conflict.↩

3 There are two types of minefields in the exercise: ones marked on the teams' patrol map which they should confirm in their patrol log and report; and previously unknown minefields about which the team should notify the NCS. The minefield in this excerpt is the one of the former.↩

4 The page DRV is presenting to TL shows the flags and the uniforms of the two conflicting imaginary nations, Blueland and Greyland.↩

5 Conscripts from a nearby garrison are used in the exercise for roleplaying soldiers of the conflicting nations as well as other UN peacekeepers operating in the area.↩