Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Towards a Multimodal Account of Post-Positioned Question Tags in Jordanian Arabic Conversation

Juman Al-qaoud

University of Cologne

Abstract

This study explores the multimodal features of post-positioned question tags (PPQTs) and their temporal alignment, by using Conversation Analysis and interactional linguistics approaches. Data come from 20 hours of audio and video recordings of casual Jordanian Arabic conversations among 70 university students and graduates in Irbid City. By drawing on Jefferson (1981), Pomerantz (1984), and Stivers and Rossano (2010), the present microanalysis shows that PPQTs, such as sˤaħ? (‘right?’), together with specific nonverbal cues, pursue responses after an initial lack of uptake, while acknowledging their non-turn yielding functions.

Keywords: multimodal communication, post-positioned question tags (PPQTs), response pursuits, Conversation Analysis, interactional linguistics

1. Introduction

Nowadays, considerable research explores human communication from a multimodal perspective by analyzing verbal language alongside visual and prosodic cues such as hand gestures, head movements, facial signals, gaze, and intonation (for example, Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, 1996; Schegloff, 1998; Enfield, 2009; Goodwin, 2010; Mondada, 2013). Despite the increasing interest, empirical studies on the multimodal properties of Jordanian Arabic interaction are lacking. As part of a more extensive research on tag questions (TQs) in Jordanian Arabic conversations, this study bridges this gap by examining how post-positioned question tags (PPQTs) perform various interactional functions, including eliciting responses after a dispreferred response or a lack thereof. By considering all the semiotic modes that may play a role in eliciting responses, this research embraces a multimodal perspective, which distinguishes it from previous studies on Arabic tag questions.

A post-positioned question tag (PPQT) is used in this study to refer to the question tag (QT)1 that appears at some distance from the statement it belongs to (i.e., the anchor; see Lakoff, 1973; Huddleston & Pullum, 2002; Hepburn & Potter, 2011; Gómez González & Dehé, 2020; Gómez González & Silvano, 2022), whether it is preceded by a lengthy gap, an exclusively nonverbal element, or by a combination of verbal and nonverbal elements. Jefferson (1981) discusses instances of the German Ne? (‘Right?’), by highlighting its occurrence at some distance from the utterance with which it is associated. She discusses this phenomenon in the context of response solicitation, particularly in post-gap position and following the completion of a short response. The term ‘post-positioned tag’ was coined by Stivers and Rossano (2010, p. 20) to refer to a tag produced with rising intonation and direct gaze and designed to elicit a response. Pioneering work by Schegloff (1968) and Schegloff & Sacks (1973) shows that specific actions such as offers and requests typically make particular responses relevant, and that the absence of a response is often treated as a communicative failure. Stivers and Rossano (2010) expand on this by showing that speakers prompt responses through a combination of social action, sequential position, and turn-design features, such as interrogative syntax, prosody, recipient-focused epistemicity, and speaker’s gaze.

Questions frequently arise in conversations to serve essential social functions such as requesting information, making invitations, offering help, and delivering criticisms (Levinson, 2013). Research indicates that questions often involve facial signals like eyebrow movements (Ekman, 1979; House, 2002; Bavelas, Gerwing, & Healing, 2014; Borràs-Comes, Kaland, Prieto, & Swerts, 2014; Torreira & Valtersson, 2015; Clift & Rossi, 2023; Nota, Trujillo, & Holler, 2023) and direct gaze (Argyle & Cook, 1976; Rossano, Brown, & Levinson, 2009). Several studies highlight the importance of studying TQs multimodally. For instance, Yang (2015) explains that the tag question duì bù duì (‘right?’) in Mandarin serves different interactional functions depending on its sequential position, with visual behaviors playing a crucial role. Tsai (2019) emphasizes the necessity of systematic multimodal analysis of the situated context in talk-in-interaction to fully understand the interactional and interpersonal nature of tag questions (p. 327).

My larger-scale research on all types of TQs in Jordanian Arabic adopts the Conversation Analysis (CA) and Interactional Linguistics (IL) approaches. CA offers a method to analyze face-to-face interactions by considering the integrated effects of all multimodal practices in constructing coherent courses of action (Goodwin, 2000a, 2000b; Stivers & Sidnell, 2005). IL examines language as a semiotic system relevant to interaction, by aiming to explain “how linguistic structures and patterns of use are shaped by, and themselves shape, interaction” (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, 2001, p. 1). By using both approaches, I can assess how TQs are delivered through a movement-speech ensemble that aims to confirm assumptions, check understanding, draw attention, request information, and close topics, among other functions.

This study specifically explores the association between the form, the intonational pattern, and the conveyed function of PPQTs in spontaneous Jordanian Arabic. It also shows that upper-body movements, such as eyebrow raises and head nods, often co-occur within the PPQTs, particularly those oriented toward seeking information or confirmation. The studied PPQTs display temporal alignment between most of the examined upper-bodily movements and prosodic prominence markers. By highlighting the forms and communicative functions of PPQTs and emphasizing their role in response solicitation, this study aims at providing new insights into the impact of utterance position on eliciting responses.

In the following sections, I begin by detailing the process of collecting the video-recorded data. I then introduce a modified coding scheme used for data annotation and describe the transcription procedure that produces the examples presented later. The analysis follows, focusing on the forms, occurrences, and sequential positions of PPQTs in six excerpts, which feature multimodal transcription and accompanying screenshots. Finally, I discuss the findings and present the conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Data collection

The data was collected in 2022 in Irbid, a city in northern Jordan. Participants were recruited via Facebook by posting an online recruitment form on various university pages and groups. To control for factors such as levels of acquaintance, proximity, and social hierarchies, participants were asked to bring conversation partners they knew well. The study also controlled for age, education level, and gender. Only individuals within a specific age range were included, and participants were required to have at least a high school education to minimize variations related to educational background.

As online recruitment alone did not yield a sufficient number of participants, additional recruitment was conducted in person through direct contact with friends of friends, with preliminary consent obtained prior to participation. In total, 70 native speakers of Jordanian Arabic, specifically from Irbid City, were recorded. The sample comprised 44 females and 26 males, engaged in conversations in groups of 2 to 5 individuals across various settings, including restaurants, cafés, universities, homes, libraries, laboratories, and clothing stores. Participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 39, with 21 being the most common age. The conversations were naturally occurring, with no assigned discussion topics.

The recordings ranged from 25 to 95 minutes, with a total duration of 1,198.36 minutes (approximately 19.97 hours).

2.2 Data annotation and transcription

All recordings were trimmed to include only the anchor, the element(s) following the anchor, the QT, the response, and some surrounding context. This resulted in shorter recordings ranging from 5 to 41 seconds.

The trimmed audio recordings were initially annotated and analyzed using Praat (Boersma & Weenink, 2023) for acoustic analysis. This included measuring the duration of pauses and gaps, identifying accented syllables and pitch patterns, and analyzing final intonation. In particular, Praat was used to measure the duration of gaps and pauses before and after each QT. During this process, interval tiers were manually labeled, with a focus on PPQTs and their pitch-prominent syllables.

Following the initial coding in Praat, all instances of PPQTs that met the study’s criteria (see Section 3) were selected. The primary steps of notation, coding, and analysis were then conducted using ELAN (2023). Speech and upper-body movements were annotated according to the guidelines of the Linguistic Annotation System for Gestures (LASG) (Bressem, Ladewig, & Müller, 2013), with modifications detailed at the end of this sub-section.

For all examples, the original Arabic script was included, although the primary analysis was conducted using the transliterated utterances.2 Upper-body movements were coded if they directly preceded, co-occurred with, or followed the PPQTs. Gestural forms were annotated separately for each hand, while eyebrow movements were categorized as raising, lowering, or frowning. Head movements were classified into tilt, shake, nod, turn, protrusion, or slide, following the guidelines of Wagner, Malisz, and Kopp (2014). Gaze direction was annotated manually based on Kendrick, Holler, and Levinson’s (2023) distinction between gaze directed toward or away from the recipient.

Movement segmentation was performed using the ‘frame-by-frame marking procedure’ (Seyfeddinipur, 2006), which follows Kita, van Gijin, and van der Hulst’s (1998) gesture coding scheme. This method relies on video image sharpness to distinguish between transitions in gestural movement sequences, including shifts from dynamic to static phases, from static to dynamic phases, and between dynamic phases. These transitions, marked by variations in image clarity, facilitate the identification of gesture phases.

According to LASG, gestures are initially analyzed independently of speech, with their form, meaning, and function examined before assessing their relation to speech. Furthermore, since LASG only provides guidelines for annotating hand gestures and excludes other body articulators, postures, and gaze (Bressem, Ladewig, & Müller, 2013), modifications were necessary. The original LASG-based annotations were retained but reorganized according to Ladewig’s (2020) ‘integrating’ coding scheme. This approach treats speech and gestures as equally significant components of multimodal utterances and thus prevents the dominance of one modality over the other. As a result, the annotation process began with the utterance as a multimodal construction (parent tier), with gestures and speech annotated as integral elements of utterance formation. The final annotations in this study reflect the timing and meaning connections between speech and gesture by adopting the concept of ‘co-expressiveness’ (McNeill, 2005, pp. 22-23).

For multimodal data transcription, the recent transcription software DOTE (Distributed Open Transcription Environment; see McIlvenny, 2022) was used , as it provides support for both the Jeffersonian (Jefferson, 2004) and the Mondadian conventions (Mondada, 2018).3 While transcribing in DOTE, an interlinear gloss line based on the Leipzig Glossing Rules (Comrie, Haspelmath, & Bickel, 2015) was added, followed by a separate English translation line placed directly below the gloss. After exporting my transcripts to RTF files, screenshots showing the movements with arrows and shapes were added when needed.

Given the nature of this study and the need to perform qualitative microanalysis to show the correlations of all verbal and nonverbal elements involved in the production of PPQTs, the even newer software DOTEbase (McIlvenny, 2024), which provides a set of tools to support qualitative analysis of audiovisual media and DOTE transcripts, has been beneficial while still being under test.

After providing full transcriptions of the TQs and the relevant sequences, it became easier to examine speakers’ initial attempts to mobilize a response or reaction through the use of the anchor. In this study, the anchor is accompanied by features that invite a response and function as markers of a "turn-constructional unit" (TCU), as described by Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson (1974, p. 702) and later examined by Selting (1998). This is followed by a post-positioned question tag (PPQT), which may serve multiple purposes. It may pursue a response following either a lack of response or an insufficient response, thereby forming the first-pair part (FPP) of an adjacency pair and establishing the relevance of the second-pair part (SPP) as a response (Schegloff, 1968; Schegloff & Sacks, 1973; Sacks, 1992, pp. 117-125). On the other hand, it may, though less frequently, fulfill non-response-mobilizing functions, particularly when the QT does not occur as a sequence-initiating utterance (Stivers & Rossano, 2010), but rather operates as an acknowledgment, an emphatic device, or a narrative or rhetorical resource.

3. Form and Number of Occurrences of PPQTs: An Overview

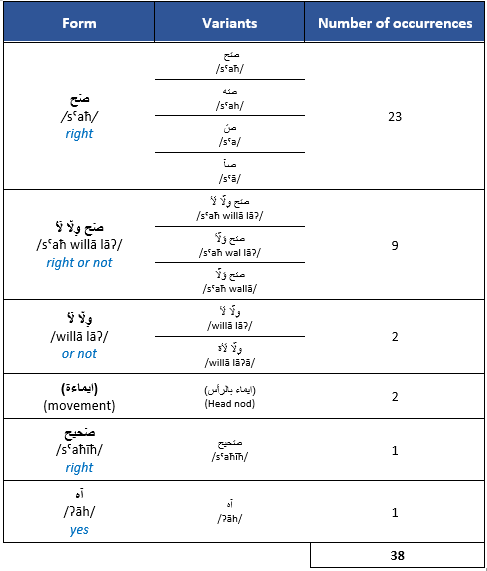

After examining 26 video recordings, 198 occurrences of TQs were identified. Of these, 38 instances, classified as TQs with post-positioned QTs, were selected for further analysis. As shown in Table 1, PPQTs appear in different lexical and phonetic forms, most frequently as sˤaħ (‘right’) and its variants with stretched, shortened, or modified forms. The second most-used form is sˤaħ willā lāʔ (‘right or not’) with three variants, the first variant being the most frequent (7 occurrences). The use of willā lāʔ (‘or not’), sˤaħīħ (‘right’), and ʔāh (‘yes’) as PPQTs is considerably less frequent. The set of 38 PPQTs examined in this study consistently includes verbal tokens.4 The transcribed examples in the next sections show that the different forms are connected to different intonation patterns and can therefore be associated with different communicative functions.

Table 1. Forms and frequencies of post-positioned question tags (PPQTs) with their variants.

The form sˤaħ (‘right’) is mentioned in other studies on colloquial Jordanian Arabic (Al-Harahsheh, 2014; Alsaraireh, Altakhaineh, & Khalifah, 2023). According to Alsaraireh, Altakhaineh, and Khalifah (2023), other forms used by Jordanian speakers are mu: sˤaħ? (‘isn’t that right?’), mu: heik? (‘correct?’), balla? (‘by the word of God?’), willa ʔna ɣltˁan? (‘Am I wrong?’), miʃ heik? (‘isn’t that correct?’), in addition to willa laʔ? (‘No?’), which is also found in Najdi Arabic (Alharbi, 2017). Some other forms used in other Arabic dialects include maː heːk? (‘is that not so?’) in Syrian Arabic (Murphy, 2014), mu? (‘right?’), sahih? (‘right?’), mu sahih? (‘isn’t (that) right?’), ha? (‘eh?’), and zain? (‘ok?’) in Iraqi Arabic (Albanon, 2017). In Egyptian Arabic, Marmorstein (2024) has identified several tag forms used for confirmation requests, including walla (‘or’)-based tags, miš kida (‘not like that’), ʔāh (‘yes’), ṣaḥḥ/ṣaḥīḥ (‘right’), ha (interjection), and mitʔakkida (‘are you sure?’ [referring to a female]). However, none of these studies consider these forms as instantiations of PPQTs.

4. Analysis of the Sequences Hosting PPQTs

PPQTs are categorized based on the immediately preceding elements in the conversation. This is an important aspect to consider, as they differ from the more widely studied QTs appended directly to the utterance to which they belong. The terms used to describe the preceding elements are chosen by the researcher and align with those used by Jefferson (1981) to describe the elements preceding the objects used for response solicitation. The sequential organization of the PPQT and the preceding element is presented in the following sub-sections in this form: anchor ⇾ element ⇾ PPQT.5 The current section aims to address the research questions mentioned at the end of Section 1, including the movement-speech package created to convey the communicative functions of the PPQTs, the co-occurrence of specific modes within PPQTs, the temporal alignment of such modes, and the possible associations between the form, the final intonational pattern and the function of the PPQTs.

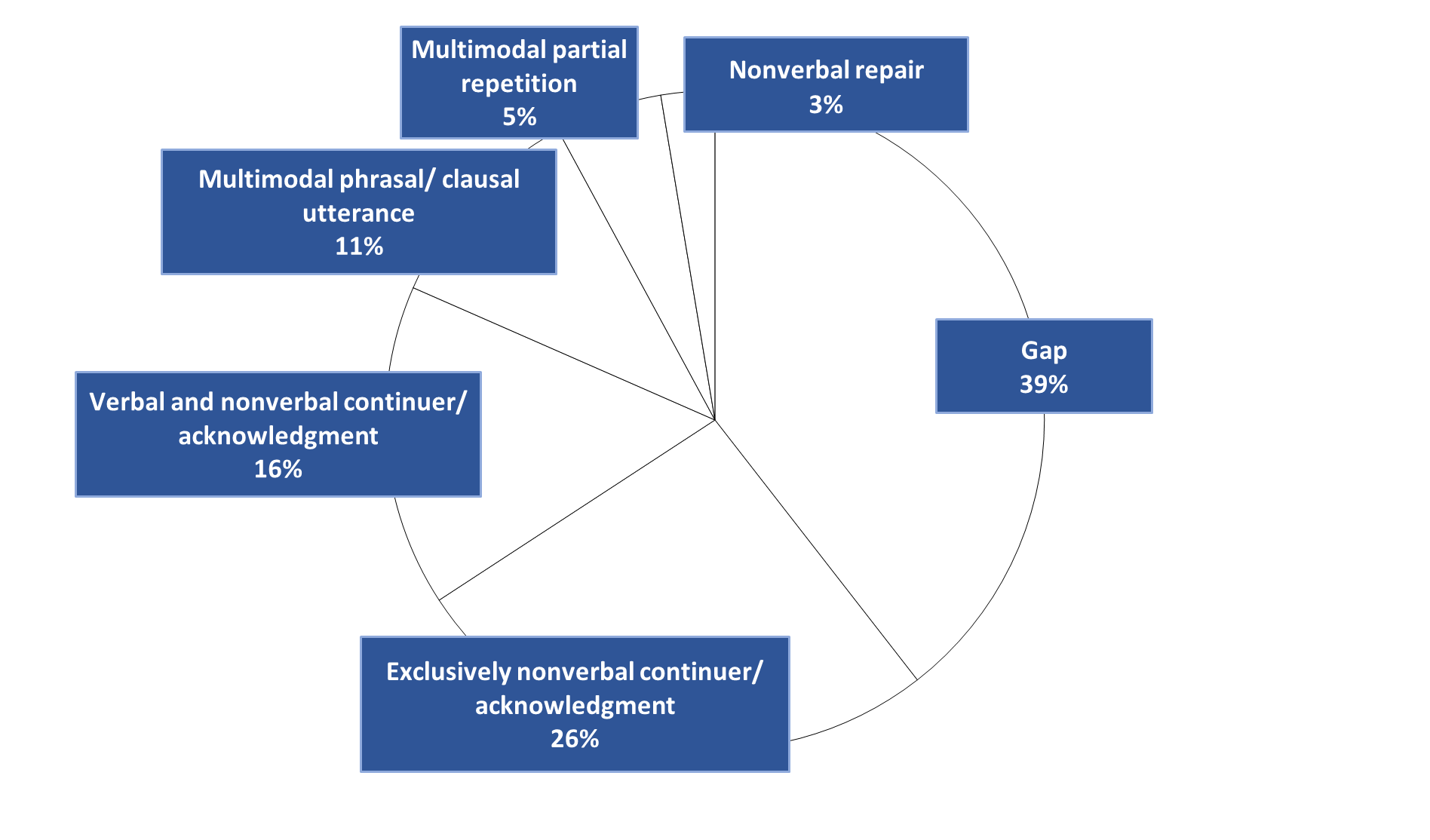

Figure 1 summarizes the categories of elements that precede the PPQTs. A noticeable number of cases involve gaps (15 occurrences), followed by an exclusively nonverbal prompting element (10 occurrences). A minimal continuer or acknowledgment with verbal and nonverbal cues occurs before the PPQTs in 6 examples, while four examples involve longer multimodal utterances (i.e., more than a one-word turn; a turn composed of a single phrase or a single clause; see Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, 2017), including collaborative completions, comments, and repair questions detected prior to the PPQTs. Two multimodal partial repetitions of a prior turn preceding the PPQTs after an acknowledgment or a longer multimodal construction by the recipient are examined as well. Finally, a nonverbal attempt at repair is detected in one of the videos, where the addressee shakes his head to demand clarification. This instance is investigated in relation to the example showing a gap preceding the PPQT.

Figure 1. Elements preceding the post-positioned question tags (PPQTs).

This section presents the multimodal features accompanying PPQTs in connection to each of the preceding element(s) by means of a representative example. Sometimes, the nonverbal components extend beyond the target utterances but are still connected to the studied aspect; therefore, they are included. All of the examples6 are multimodally coded and transcribed by using Praat, ELAN, and DOTE,7 with several arrows and shapes used in the screenshots to show upper-body movements (red arrows for head and hand movements; white arrows for gaze). The line numbers for the anchor, the PPQT, and the preceding element are all mentioned in the footnotes in each sub-section. In some lines, the interlinear glosses are not provided, either because they are not necessary or to make the transcript more readable. The utterances preceding the anchors are omitted for the sake of space in some examples, while the context is always provided.

(1) Anchor ⇾ Gap ⇾ PPQT

While keeping in mind that the most frequent transitions between turns occur with a slight gap of 200 ms (Walker & Trimboli, 1982; Stivers et al., 2009; Heldner & Edlund, 2010), a gap of more than 200 ms between the end of the anchor and the beginning of the QT was considered lengthy and included in this sub-section. The minimum gap length here is 205 ms, and the maximum is 2595 ms. Jefferson refers to this phenomenon as a “Post-Gap Response Solicitation” (Jefferson, 1981, p. 61).

Excerpt 1. (New_semester, friends talking about courses)

Open in a separate windowIn Excerpt 1 above,8 Sara, Majed, and Anwer are close friends and university students. A notable feature of the interaction in this excerpt is the long gap preceding the PPQT, which plays a crucial role in shaping the unfolding exchange. Before this moment, Majed had firmly stated that he was not registered for any courses and had no intention of enrolling, despite Sara’s persistent teasing and efforts to persuade him. The conversation leading up to this point is marked by Sara’s playful yet insistent attempts to influence Majed’s decision, while Anwer remains largely disengaged, occupied with Sara’s phone as he helps her enroll in courses.

When Sara first responds to Majed’s position in line 1, there is no immediate mutual gaze between them. Her turn concludes in line 3 while she directs her gaze at Anwer, who remains focused on the phone. The extended silence that follows, lasting 1400 ms, creates a noticeable interactional gap, during which Sara shifts her posture, turning her head and beginning a slight nod toward Majed. This delay sets the stage for her PPQT sˤā:::?9 (‘right?’) in line 5, which is produced with heightened prosodic features, including a high pitch, an elongated vowel, and an omitted final consonant. The exaggerated delivery, coupled with her gaze and nod while smiling (see Figure 1.1), suggests an attempt to re-engage Majed after the lapse in response. The nod movement is retracted before reaching the prosodically prominent marker in the accented syllable of the PPQT.

The long silence before the PPQT is significant because it amplifies the teasing function of Sara’s turn. It highlights the lack of immediate uptake from Majed, which makes her eventual prompt an interactional move intended to break the silence and reclaim his attention. The PPQT is delivered multimodally as an instance of self-initiated repair (Schegloff, Jefferson, & Sacks, 1977) by Sara, after her initial utterance in lines 2 and 3 goes unanswered due to Majed’s distraction with his phone. During another long silence of one second, Majed reacts with a head shake and raised eyebrows signaling a need for repetition or clarification (line 6).

(2) Anchor ⇾ Exclusively nonverbal continuer/acknowledgment ⇾ PPQT

This category includes instances in which PPQTs are produced after a nonverbal continuer or acknowledgment from the addressee, occurring either during or after the speaker’s anchor. In my data, these nonverbal elements include one or more nods, a blink, or a big acknowledging smile with a direct gaze.

Excerpt 2. (Waffle_place, friends talking about dating life)

Open in a separate windowIn Excerpt 2,10 the interaction between Lojain and Maryam, who are close school friends, highlights how multimodal features reinforce the confirmatory function of the PPQT. The key argument in this exchange is that Lojain uses the PPQT strategically, not only to confirm her assumption but also to elicit a more explicit response from Maryam. This occurs despite Maryam’s initial nonverbal acknowledgment, which might have otherwise sufficed as an agreement.

Before this excerpt begins, Maryam asks Lojain whether she believes no one is interested in dating her, following a prolonged discussion on the topic with multiple shifts in subject. The buildup to the PPQT is crucial: Lojain initially answers Maryam’s concern while keeping her gaze on the food. It is only in line 2 that she shifts her gaze directly toward Maryam, marking an interactional shift. In response, Maryam offers a big head nod along with a shy smile while attempting to pick up food with her fork (Figure 2.1). This silent nod, occurring before Lojain completes her utterance, suggests an acknowledgment of the statement’s truth.11 However, Lojain’s subsequent use of the PPQT in line 5 indicates that she perceives this initial response as insufficient or in need of reinforcement.

The delivery of the PPQT sˤaħ? (‘right?’) is marked by a high initial pitch and a final rising intonation and is embedded within a multimodal ensemble. Lojain accompanies the question with a series of simultaneous upper-body movements: a head turn, a nod, a direct gaze, an eyebrow raise, and eye-widening (Figure 2.2). The slicing gesture, where both hands, holding a knife and fork, move downward in a well-defined motion, perfectly aligns with the prominent syllable of the focused word (Kendon, 2004, p. 140). As described in previous studies (‘Cutting’ in Calbris, 2003, p. 33; ‘the slice’ in Streeck, 2008, pp. 161-163; ‘the slice’ in Lempert, 2017, p. 37), this slicing gesture serves a discursive function of intensification, which emphasizes Lojain’s assertion. The hand gesture and the head nod are held until Maryam provides a second response.

Maryam’s eventual response in line 6, a bigger nod while still looking at the food (Figure 2.3), reinforces the idea that the PPQT functions as a confirmatory device. While Maryam had already provided a nonverbal acknowledgment in line 3, Lojain’s PPQT appears to prompt a stronger or more explicit confirmation, likely due to Maryam’s initial gaze aversion. This aligns with Algeo’s (1990, pp. 445-446) description of confirmatory PPQTs, where the speaker, while expecting agreement, seeks additional validation. This is also evident in Lojain’s satisfied reaction, laughing and claiming to know everything about Maryam.

(3) Anchor ⇾ Verbal and nonverbal continuer/acknowledgment ⇾ PPQT

This sub-section examines PPQTs used as a prompt for a more elaborate response (Jefferson, 1981, p. 61). As described by Jefferson (1981, p. 66), this is a benign (gentle) technique used as a “Post-Response-Completion Response Solicitation of the Promptings” (Jefferson, 1981, p. 68).

Jefferson (1981, p. 60) gives examples of the short tokens that qualify as continuers or premature prior responses (yeah, right, uh huh, mm hm, oh, etc.). In my data, the one-word continuers/acknowledgments preceding the PPQTs include sˤaħ (‘right’), ʔajwa (‘yeah’), mazbūt (‘right’), ʔāh (‘yeah’), and mm hm.

Excerpt 3. (Thesis_writing, friends discussing graduate school)

Open in a separate windowIn Excerpt 3,12 the interaction between Hamzah and Hasan highlights the use of multimodal resources in negotiating knowledge and confirming shared understandings after an unfavorable minimal continuer. This minimal response signals alignment, but at the same time it prompts the use of a PPQT to elicit further elaboration. Hamzah, a lawyer with a master’s degree, engages in this exchange with Hasan, who is in the early stages of writing his thesis but intends to transfer to a course-based master’s program. Prior to this excerpt, the two discuss the challenges of writing a master’s proposal. Hamzah, already aware of Hasan’s transfer request, initiates a confirmation request with an irritated loud tone, using the phrase FAhhimnī inta fahimnī (‘YOU make me understand! Make me understand!’). The marked informal form of the question in line 1, starting with inta (‘you’) and using the negation particle miʃ (‘not’), indicates that Hamzah is not seeking new information but rather asserting his awareness of the issue to prompt a direct discussion and resolve the matter definitively.

The progression of Hamzah’s questioning further demonstrates the strategic use of multimodal elements to structure the interaction. In line 4, he poses a second question, distinct from the first, as it requests new information, an aspect reinforced by the accompanying preparation of the left-hand gesture that begins with the question and extends into line 6 (Figure 3.1 & Figure 3.2). The 1.1-second pause in line 5, during which Hamzah directs his gaze toward Hasan, serves as a cue for response. Hasan’s minimal token response, ʔajwa (‘yeah’), in line 6, coupled with rising intonation and direct gaze, signals an expectation for Hamzah to continue (Figure 3.2).

Hamzah’s immediate follow-up with the stressed PPQT sˤaħ? (‘right?’) in line 7, accompanied by a rising intonation, eyebrow raise, eye-widening, a stroke and post-stroke hold of the left-hand gesture, head nod, and direct gaze at Hasan, emphasizes his demand for a more explicit response. His arm movement, transitioning into a cyclic gesture (Ladewig, 2010, 2011, 2014, 2024; Ruth-Hirrel, 2018) before forming an Open Hand Oblique Gesture (Kendon, 2004, p. 216) directed at Hasan, functions as a critical remark (Figure 3.3). Importantly, these nonverbal cues persist until Hasan provides a more ‘adequate’ response in line 8, reinforcing Hamzah’s insistence on a conclusive acknowledgment.

This sequence illustrates how the interplay between the verbal and nonverbal elements serves to enforce conversational expectations. Hasan’s continuer in line 6 suggests his assumption that Hamzah has not yet completed his turn, whereas the PPQT in line 7 signals that Hamzah is indeed finished and is expecting an extended favorable response from Hasan. The multimodal ensemble thus offers Hasan a ‘next opportunity to show that he has taken the point’ (Jefferson, 1981, p. 63). Moreover, this use of the PPQT aligns with Algeo’s (1990, p. 445) categorization of TQs’ informational function, where the speaker conveys an assumption but seeks confirmation without fully presuming the respondent’s answer.

(4) Anchor ⇾ Multimodal phrasal/clausal turn ⇾ PPQT: Collaborative completion as an example

This group includes different kinds of multimodal phrases or clauses preceding the PPQTs, which are more complex than minimal responses such as continuers or acknowledgments. These multimodal phrases or clauses include collaborative completions,13 comments by any of the co-participants, and repair questions.

Excerpt 4. (A chat on the sidewalk - discussing jobs)

Open in a separate windowIn Excerpt 4,14 Rami, Namir, and Salim are neighbors talking about Rami’s career and current freelancing preferences. Namir is captured with one camera, and his movements are taken into consideration, but only screenshots from the other camera showing Rami are included in the transcripts for visual clarity. A full screenshot of all participants can be found in Appendix B.

Prior to this excerpt, Rami discusses his father’s lifelong military service, noting the lack of financial savings. By drawing a comparison, he expresses regret over spending much of his life in law rather than starting a trade business earlier, which he now does by owning a Shisha shop. The conversation takes place in front of the shops where Rami and Salim work.

In line 1, Rami recruits Namir’s assistance to complete his utterance based on their prior discussion. This recruitment is marked by the use of an ‘if’ dependent clause, rising intonation at the turn’s end, an upward pointing gesture with the index finger (preparation and stroke), and a noticeable left eyebrow raise (Figure 4.1). Namir recognizes this invitation for completion but first signals understanding with tˤajeb sˤādig ʔAH (‘yes, you’re right’) in line 3 before providing the apodosis of Rami’s conditional utterance. Up to this point, Namir maintains eye contact with Rami before briefly gazing away to deliver his completion. Meanwhile, Rami releases his pointing gesture during Namir’s turn, transitioning into a new hand movement with both the index finger and thumb extended (Figure 4.2).

In line 4, Rami immediately follows with a sped-up PPQT sˤaħ willā lāʔ. (‘right or not.’),15 initiated with a big head nod and pronounced with final falling intonation (Figure 4.3). His fingers then transition into a Grappolo G-family Gesture (Figure 4.4), where the index finger and thumb touch the other fingers, an emphatic movement often used to “extract the essence” of a topic (Kendon, 2004, p. 236). The prominent syllable of the PPQT aligns with the stroke and apex of his hand movement, his direct gaze at the addressee, and the peak of his head nod. Here, the PPQT is non-turn-yielding and does not function as a pursuit of further response. Instead, it serves as a topic-closing device after the satisfactory completion in line 3. This is evident in line 6, where Rami seamlessly continues with a new utterance without waiting for additional confirmation.

(5) Anchor ⇾ Phrase/ Clause⇾ Multimodal Partial repetition of the anchor + PPQT

In cases where responses are not immediately forthcoming, self-repetition serves as a repair mechanism, with the addition of the PPQT to pursue a response. In such instances, the anchor is partially repeated. This observation aligns with Schegloff’s (1968) comments on the nature of repeated elements: “Repetition does not require that the same lexical item be repeated; rather, successive utterances are each drawn from the class of items that may be summonses, although the particular items that are used may change over some string of repetitions” (p. 1085).

Excerpt 5. (Chat over coffee - three school friends discussing their last gatherings)

Open in a separate windowWhile the direct appending of a QT to an utterance is not the focus of this study, what makes these two examples unique is the speakers' multimodal partial repetition of their own completed preceding turn (i.e., the anchor) combined with a PPQT. I argue that the combination of a partial repetition of the original utterance and a tag cannot be fully understood by recipients without first hearing the initial utterance. This means that the interrogative particle tags refer to the full utterances produced earlier; thus, the tags can be considered PPQTs because they are separated from their original anchors.

Additionally, the elements preceding this combination, such as the addressee’s minimal acknowledgment and a longer multimodal utterance, align these cases with other PPQTs analyzed in this study, as seen in Excerpt 5.16 In both examples in this excerpt, the addressee, Tala, either provides a minimal response or is distracted by answering a previous question. In turn, Sujood and Fatima partially repeat the anchor before directly attaching a QT to elicit a clearer response in both instances.

Tala, Sujood, and Fatima are close friends from high school and college. Prior to this excerpt, they attempt to recall their last meeting. Tala and Sujood seem to remember the gathering, while Fatima asks for help to jog her memory. Their conversation shifts to a green shirt that Tala bought during their last holiday meeting. Tala recalls that they laughed at the shirt and compared its color to a school uniform. At this moment, Sujood playfully calls out, bagdo:nis bagdo:nis (‘parsley, parsley’), mimicking Jordanian street vendors. Fatima extends the joke by adding, dʒardʒīr dʒardʒīr (‘arugula, arugula’), referencing a common joke in Jordan about the specific shade of green.

In line 1, Tala, seemingly upset by the comparison, insists that people at the university called it ħilo (‘pretty’) the previous day. Sujood interrupts her in line 2, asserting that Tala wore the shirt yesterday. Tala acknowledges with mm hm in line 4 while none of them maintain mutual gaze (Figure 5.1).

Due to overlap, Sujood may not have heard Tala say mbāriħ (‘yesterday’) in line 1. Seeking confirmation, she partially repeats her own previous turn and attaches the PPQT sˤaħ? (‘right?’) in line 6. This PPQT is produced with rising intonation, a slight head nod, a direct gaze at Tala after a head turn, and a partial blink (Figure 5.2). The apex of the nod coincides with the prominent syllable’s vowel. This pattern aligns with research on embodied repair sequences, where bodily movements such as nodding, gaze shifts, and eyebrow movements are co-produced with speech to modulate the force of the repair (Goodwin, 1981, p. 112; Enfield et al., 2013; Kendrick, 2015, p. 178; Oloff, 2018; Stukenbrock, 2018, pp. 54-56).

Tala’s response, however, is delayed due to competing attentional demands, as she is simultaneously attending to Fatima’s interjection. When she eventually responds in lines 9, 10, and 13, she negates Sujood’s assumption by specifying that she actually wore the shirt the day before. The temporal correction ʔawwal mbāriħ (‘the day before yesterday’) carries implications for epistemic authority: Tala asserts privileged knowledge of the event while subtly marking Sujood’s assumption as incorrect. Sujood’s disappointed reaction to ʔawwal mbāriħ (‘the day before yesterday’) in line 10 suggests that she was almost certain the correct answer was mbāriħ (‘yesterday’), as indicated by her exaggerated mouth movement to the side.

Fatima, perhaps sensing Tala’s discomfort, comments in line 8 that "[the shirt] looks different when it’s worn" and in line 11 that "I remember it was pretty." Tala does not immediately respond, as she is occupied with answering Sujood’s question in line 6. However, she gazes at Fatima whenever an utterance is directed toward her. In line 13, Tala repeats the response she first gave to Sujood in line 10, just as Fatima interrupts her. Tala’s preoccupation with answering Sujood leads Fatima to repeat part of her previous turn and attach a tag in line 14.

Fatima’s turn in line 14 is particularly significant: she recycles a key lexical item from her prior turn (ħilo - ‘pretty’) and attaches a PPQT (sˤā::h? - ‘right?’). This PPQT is phonetically marked by a noticeably lengthened vowel, and the final consonant is replaced by the voiceless glottal fricative /h/, creating a softer, possibly more inviting tone. The PPQT is accompanied by rising intonation, an eye squint, an eyebrow frown, a head nod, and a direct gaze toward Tala (Figure 5.3). The prosodically prominent part of the PPQT aligns with the stroke of the head nod while the eyebrow frown is retracted.

Shortly after, Tala provides a positive response, ʔāh (‘yes’), in line 16, accompanied by a large nod (Figure 5.4). This combination of partial repetition, a PPQT, and multimodal cues appear to function as an attention-drawing strategy, re-engaging Tala after her distraction and bringing a closure to a topic that may have made her uncomfortable.

The systematic use of partial repetition, PPQTs, and multimodal cues in these two examples illustrates how speakers manage delayed uptake, misalignment, and attentional disengagement. These PPQTs are not merely confirmation checks; rather, they function as complex multimodal repair tools that regulate epistemic access, re-engage distracted interlocutors, and smooth over minor interactional misalignments.

(6) Anchor ⇾ Nonverbal repair ⇾ PPQT

This sub-section covers the recipient's nonverbal requests for clarification or repetition as forms of other-initiated repair (Schegloff, 2000), which occur before the speaker employs a PPQT to pursue a response. Stivers and Robinson (2006, p. 369) demonstrate that answer responses and non-answer responses can be ranked in terms of a preference for progressivity. Non-answer responses, such as “I don’t know” or repair initiations (whether verbal or nonverbal), are treated as dispreferred alternatives to answer responses; still, they facilitate the sequence’s progression toward completion. Although research on bodily conduct as a method for other-initiated repair without co-occurring speech exists, it has received less attention than other forms of repair initiation that involve speech (Ekman, 1979; Seo & Koshik, 2010; Kendrick, 2015; Mortensen, 2016; Jokipohja & Lilja, 2022).

Excerpt 6. (New_semester, friends talking about courses)

Open in a separate windowThis example illustrates a PPQT preceded by a nonverbal repair initiation. It continues from Excerpt 1, where Majed’s attention is successfully captured by the first PPQT in line 5. Prior to the current moment, Majed is focused on his phone and does not hear Sara’s utterances in lines 1-3. This becomes evident in his reaction in line 6 of Excerpt 6, where he shakes his head, signaling a request for clarification (Figure 6.1). In response, Sara produces a large head nod (Figure 6.2), then releases it before softly repeating sˤaħ? (‘right?’) with rising intonation in line 7. The shorter, quieter articulation of this second PPQT, along with a visible smile on Sara’s face, suggests that she has successfully regained Majed’s attention and is now teasing him. Sara averts her gaze before Majed responds, indicating that the PPQT serves to maintain his attention rather than eliciting an actual answer. In line 8, Anwer attempts to shift the topic by asking Sara for her university password to enroll her in more courses. The topic is later revisited in the recording, when Majed appears irritated by Sara’s persistence.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

This study enhances the understanding of tag questions (TQs) in Arabic by introducing post-positioned question tags (PPQTs), QTs that appear at a distance from their anchor, a previously unexamined subgroup in Jordanian Arabic. Through an analysis of 38 naturally occurring instances, this research uncovers new QT forms and variants, such as sˤaħ willā lāʔ. (‘right or not.’) and ʔāh? (‘yes?’), which have not been previously investigated in Jordanian Arabic. The multimodal nature of these PPQTs is examined in detail using Praat, ELAN, DOTE, and DOTEbase for annotation and transcription. The findings highlight the linguistic components, acoustic features, upper-body movements, and temporal alignment of these modes.

A key finding is that PPQTs are consistently preceded by gaps, exclusively nonverbal continuers/acknowledgments, nonverbal and verbal continuers/acknowledgments, and multimodal phrasal/clausal utterances, including collaborative completions, comments, and repair questions. Less frequent preceding elements include multimodal partial repetitions of a previous turn and nonverbal repair attempts.

A distinction is made in this study between response-mobilizing and non-response-mobilizing PPQTs. The response-mobilizing PPQTs occur as first-pair parts and function as self-initiated repair strategies following a lack of response or an inadequate response (as seen in Excerpts 1, 2, 3, and 5). The non-response-mobilizing PPQTs primarily serve as acknowledgments of the recipients’ utterances, usually with no time given for a response (e.g., Excerpts 4 and 6). The distinction between response-mobilizing and non-mobilizing tags has been addressed in several studies on languages other than Arabic. However, explicit differences in distinguishing them, whether based on their position in sequences or on the accompanying multimodal features, have not been the primary focus (Algeo, 1990; Tottie & Hoffmann, 2006; Columbus, 2010; Axelsson, 2011; Mithun, 2012; Tomaselli & Gatt, 2015; Gómez González & Dehé, 2020; Gómez González & Silvano, 2022).

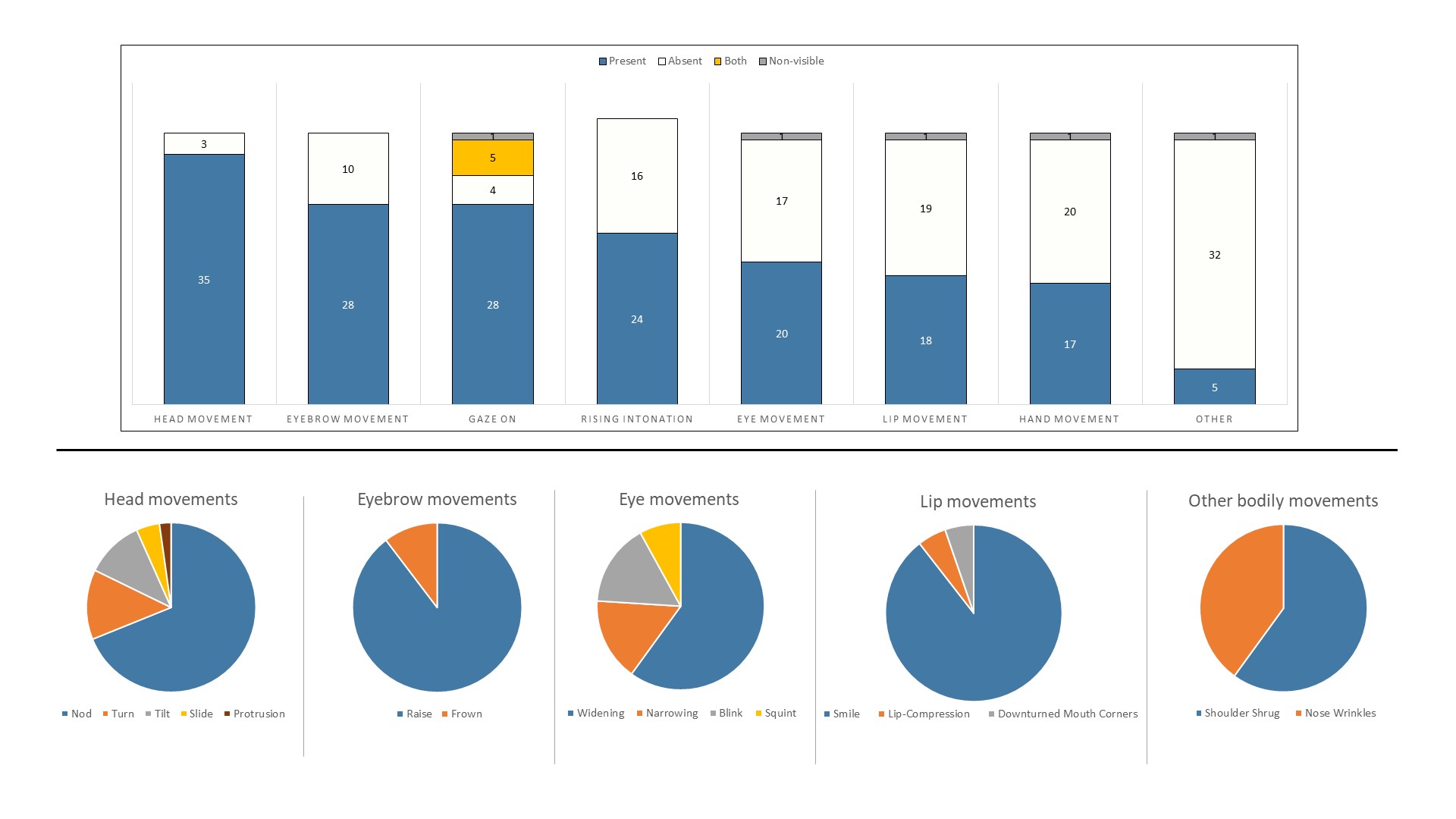

The findings of this study reveal that most analyzed hand, head, and eyebrow movements begin before the onset of the related speech unit (i.e., the PPQT), thus reinforcing the role of multimodal cues in structuring interaction. The majority of PPQTs in the analyzed conversations are accompanied by specific nonverbal features such as head nodding, eyebrow-raising, gazing at the addressee, and rising intonation (see Figure 2 for an overview). Notably, head and eyebrow movements co-occur most frequently, in 26 out of the 38 cases; see the representative examples in Excerpts 2, 3, and 5. These findings align with previous studies on time alignment in multimodal communication, which consistently show that a movement tends to precede its lexical affiliate to facilitate rapid comprehension of the intended message (Ferré, 2010; Kaukomaa, Peräkylä, & Ruusuvuori, 2013; Kendrick & Holler, 2017; Nota, Trujillo, & Holler, 2021; ter Bekke, Drijvers, & Holler, 2024).

Furthermore, this study demonstrates that the stroke phase of most hand and eyebrow movements coincides with the stressed syllable in the focused word within the PPQT, which reinforces the relationship between visual and prosodic prominence. This pattern is evident in Excerpts 2, 3, 4, and 5. These findings support prior research on multimodal prominence, which has shown that visual prominence cues often align with prosodically prominent speech features to create an integrated multimodal prominence (Loehr, 2007; Rochet-Capellan et al., 2008; Swerts & Krahmer, 2010; Ambrazaitis & House, 2017; Rohrer, 2022).

Finally, as for the form-intonation-function relationship of PPQTs, the present study shows that different forms exhibit distinct intonation patterns. In the analyzed conversations, sˤaħ willā lāʔ. (‘right or not.’) is consistently produced with falling intonation to emphasize a point before elaborating, seek confirmation, invite a third participant’s interference, ensure mutual understanding, hold the addressee’s attention, and close a topic (e.g., Excerpt 4), but never to seek information. Conversely, sˤaħ? (‘right?’) with rising intonation serves multiple functions, such as emphasizing a topic to build common ground, holding the addressee’s attention, seeking confirmation (e.g., Excerpts 2 & 5), drawing attention after distraction (e.g., Excerpts 1 & 5), teasing (e.g., Excerpt 6), and requesting information (e.g., Excerpt 3). These findings indicate a direct association between the two PPQT forms, their final intonation contours, and their discourse functions. A notable distinction between the two forms becomes particularly evident in instances where PPQTs are employed to perform an information-requesting function. All instances of PPQTs that mobilize a response or minimal reaction involve a turn transition, with the recipient providing a delayed but appropriate response.

These results can be contextualized within prior research on the form-intonation-function relationship of TQs. Several studies have explored the connection between the final intonational contour of TQs and their discourse functions (e.g., Sadock, 1974; Rando, 1980; Reese & Asher, 2007). In the context of Arabic, Albanon’s (2017) study on Iraqi TQs found that intonation plays a crucial role in distinguishing between interaction-initiating TQs, which are delivered with neutral or falling intonation, and fact-finding TQs, which are produced with rising intonation. Additionally, Alsaraireh, Altakhaineh, and Khalifah’s (2023) investigation of Jordanian Arabic Facebook comments revealed a correlation between TQ function and final intonation, with gender-based differences in usage. Their focus group findings suggest that females tend to use polite and indirect language, employing rising intonation to seek agreement, whereas males use direct and assertive language, producing TQs with falling intonation to challenge or assert dominance. The current study extends these discussions by illustrating how a specific type of TQ in spoken Arabic interaction demonstrates systematic associations between form, intonation, and function, an aspect that has not been explored in previous research on PPQTs.

Moreover, this study builds on previous research that has documented various QT forms across different Arabic dialects (Sailor, 2009; Al-Harahsheh, 2014; Murphy, 2014; Albanon, 2017; Alharbi, 2017; Alsaraireh, Altakhaineh, & Khalifah, 2023; Marmorstein, 2024) by introducing a previously unexamined subgroup of question tags (QTs) in Jordanian Arabic, namely post-positioned question tags (PPQTs). Specifically, it highlights the multimodal nature of PPQTs by identifying new forms, examining interactional sequential patterns, and exploring the interplay between verbal and nonverbal cues. It also offers insights into the communicative functions of PPQTs in natural conversation. These forms are used to elicit responses following unfavorable or missing replies and, in some cases, serve various non-turn-yielding functions.

Figure 2. Post-positioned question tags (PPQTs) with the target upper-body movements and final intonation patterns.

Acknowledgment

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my PhD supervisor, Prof. Dr. Anna Bonifazi, for her invaluable guidance, insightful comments, and continuous encouragement. I am especially thankful to Dr. Constantijn Kaland, Dr. Maria Lialiou, and Janne Lorenzen for their advice on the prosodic component of this research and their assistance with Praat. I am also deeply grateful to Prof. Jörg Zinken and his team at IDS Mannheim for their support. Finally, I extend my sincere appreciation to the participants of this study for their time and cooperation.

References

Albanon, R. (2017). Gender and tag-questions in the Iraqi dialect. English Language, Literature & Culture, 2(6), 105-114.

Algeo, J. (1990). It's a myth innit? Politeness and the English tag question. In C. Ricks & L. Michaels (Eds.). The state of the language (pp. 443-450). University of California Press.

Al-Harahsheh, A. (2014). Language and gender differences in Jordanian spoken Arabic: A sociolinguistics perspective. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 4(5), 872-882.

Alharbi, B. (2017). The syntax of copular clauses in Arabic [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee]. Retrieved from https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1573/

Almaany. (n.d.). ṣaħ [صح]. Almaany Dictionary. Retrieved from https://www.almaany.com/ar/dict/ar-en/%D8%B5%D8%AD/

Alsaraireh, M. Y., Altakhaineh, A. R. M., & Khalifah, L. A. (2023). The use of question tags in Jordanian Arabic by Facebook users. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 10(1). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2023.2261198

Ambrazaitis, G., & House, D. (2017). Multimodal prominences: Exploring the patterning and usage of focal pitch accents, head beats and eyebrow beats in Swedish television news readings. Speech Communication, 95, 100-113. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2017.08.008

Argyle, M., & Cook, M. (1976). Gaze and mutual gaze. Oxford, England: Cambridge University Press.

Axelsson, K. (2011). Tag questions in fiction dialogue (Doctoral dissertation). University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2077/24047

Bavelas, J. B., Gerwing, J., & Healing, S. (2014). Hand and facial gestures in conversational interaction. In T. Holtgraves (Ed.). The Oxford handbook of language and social psychology (pp. 245-263). Oxford University Press.

Biezma, M., & Rawlins, K. (2012). Responding to alternative and polar questions. Linguistics and Philosophy, 35(5), 361-406.

Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (2023). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer (Version 6.3.09) [Computer software]. http://www.praat.org/

Borràs-Comes, J., Kaland, C., Prieto, P., & Swerts, M. (2014). Audiovisual correlates of interrogativity: A comparative analysis of Catalan and Dutch. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 38(1), 53-66.

Bressem, J. (2013). A linguistic perspective on the notation of form features in gestures. In C. Müller, A. Cienki, E. Fricke, S. H. Ladewig, D. McNeill, & J. Bressem (Eds.). Body - language - communication: An international handbook on multimodality in human interaction (pp. 1079-1098). Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

Bressem, J., Ladewig, S. H., & Müller, C. (2013). Linguistic annotation system for gestures (LASG). In C. Müller, A. Cienki, E. Fricke, S. H. Ladewig, D. McNeill, & J. Bressem (Eds.). Body - language - communication: An international handbook on multimodality in human interaction (pp. 1098-1125). Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter.

Calbris, G. (2003). From cutting an object to a clear cut analysis: Gesture as the representation of a preconceptual schema linking concrete actions to abstract notions. Gesture, 3(1), 19-46. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1075/gest.3.1.03cal

Chafe, W. (1994). Discourse, consciousness, and time: The flow and displacement of conscious experience in speaking and writing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Clift, R., & Rossi, G. (2023). Speaker eyebrow raises in the transition space: Pursuing a shared understanding. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 6(3). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v6i3.142897

Columbus, G. (2010). A comparative analysis of invariant tags in three varieties of English. English World-Wide, 31(3), 288-310. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1075/eww.31.3.03col

Comrie, B., Haspelmath, M., & Bickel, B. (2015). Leipzig glossing rules: Conventions for interlinear morpheme-by-morpheme glosses. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Retrieved from https://www.eva.mpg.de/lingua/pdf/Glossing-Rules.pdf

Couper-Kuhlen, E., & Selting, M. (1996). Prosody in conversation: Interactional studies. Cambridge University Press.

Couper-Kuhlen, E., & Selting, M. (Eds.). (2001). Studies in interactional linguistics. John Benjamins Publishing.

Couper-Kuhlen, E., & Selting, M. (2017). Interactional Linguistics: Studying Language in Social Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

De Stefani, E. (2021). Embodied Responses to Questions-in-Progress: Silent Nods as Affirmative Answers. Discourse Processes, 58(4), 353-371. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2020.1836916

Ekman, P. (1979). About brows: Emotional and conversational signals. In P. Ekman (Ed.). Human ethology (pp. 163-202).

ELAN (Version 6.7) [Computer software]. (2023). Nijmegen: Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, The Language Archive. Retrieved from https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/elan

Enfield, N. J. (2009). The Anatomy of Meaning: Speech, Gesture, and Composite Utterances. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Enfield, N. J., Dingemanse, M., Baranova, J., Blythe, J., Brown, P., Dirksmeyer, T., Drew, P., Floyd, S., Gipper, S., Gísladóttir, R. S., Hoymann, G., Kendrick, K. H., Levinson, S. C., Magyari, L., Manrique, E., Rossi, G., Roque, L. S., & Torreira, F. (2013). Huh? What? - A first survey in twenty-one languages. In M. Hayashi, G. Raymond, & J. Sidnell (Eds.), Conversational repair and human understanding (pp. 343-380). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511757464.012

Farag, R. (2019). Conversation-analytic transcription of Arabic-German talk-in-interaction. In Working Papers in Corpus Linguistics and Digital Technologies: Analyses and Methodology (Vol. 2, pp. 50). University of Szeged. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.14232/wpcl.2019.2

Ferré, G. (2010). Timing relationships between speech and co-verbal gestures in spontaneous French. Language Resources and Evaluation, Workshop on Multimodal Corpora (pp. 86-91). Valetta, Malta.

Goodwin, C. (1981). Conversational organization: Interaction between speakers and hearers. Language in Society, 12(1), 89-92. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500009647

Goodwin, C. (2000a). Practices of seeing: Visual analysis - An ethnomethodological approach. In T. van Leeuwen & C. Jewitt (Eds.). Handbook of visual analysis (pp. 157-182). London: Sage Publications.

Goodwin, C. (2000b). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 32(10), 1489-1522.

Goodwin, C. (2010). Multimodality in human interaction. Calidoscópio, 8(2), 85-98. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.4013/cld.2010.82.01

Gómez González, M.Á., & Dehé, N., (2020). The pragmatics and prosody of variable tag questions in English: Uncovering function-to-form correlations. Journal of Pragmatics, 158, 33-52.

Gómez González, M. Á., & Silvano, P. (2022). A functional model for the tag question paradigm: The case of invariable tag questions in English and Portuguese. Lingua, 272. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2022.103255

Heldner, M., & Edlund, J. (2010). Pauses, gaps and overlaps in conversations. Journal of Phonetics, 38(4), 555-568. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wocn.2010.08.002

Hellmuth, S., & Almbark, R. (2019). Intonational variation in Arabic Corpus 2011-2017 [Data collection]. UK Data Archive. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-852878

Hepburn, A., & Potter, J. (2011). Recipients designed: Tag questions and gender. In S. A. Speer & E. Stokoe (Eds.). Conversation and gender (pp. 135-152). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

House, D. (2002). Perception of question intonation and facial gestures. Proceedings of the International Conference on Spoken Language Processing.

Huddleston, R., & Pullum, G. K. (2002). The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Jefferson, G. (1981). The abominable “ne?”: A working paper exploring the phenomenon of post-response pursuit of response (Occasional Paper No.6). Manchester, England: University of Manchester, Department of Sociology.

Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In G. H. Lerner (Ed.). Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 13-31). Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Jokipohja, A. K., & Lilja, N. (2022). Depictive Hand Gestures as Candidate Understandings. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 55(2), 123-145. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2022.2067425

Kaukomaa, T., Peräkylä, A., & Ruusuvuori, J. (2013). Turn-opening smiles: Facial expression constructing emotional transition in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 55, 21-42. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2013.05.006

Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible action as utterance. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Kendrick, K. H. (2015). The intersection of turn-taking and repair: The timing of other-initiations of repair in conversation. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 250. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00250

Kendrick, K. H., & Holler, J. (2017). Gaze direction signals response preference in conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 50(1), 12-32.

Kendrick, K. H., Holler, J., & Levinson, S. C. (2023). Turn-taking in human face-to-face interaction is multimodal: Gaze direction and manual gestures aid the coordination of turn transitions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 378(1875). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2021.0473

Kita, S., van Gijn, I., & van der Hulst, H. (1998). Movement phases in signs and co-speech gestures, and their transcription by human coders. In I. Wachsmuth & M. Fröhlich (Eds.). Gesture and Sign Language in Human-Computer Interaction. GW 1997. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Vol. 1371, pp. 23-35). Berlin, Germany: Springer. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/BFb0052986

Ladewig, S. H. (2010). Beschreiben, suchen und auffordern: Varianten einer rekurrenten Geste. Sprache und Literatur, 41(1), 89-111.

Ladewig, S. H. (2011). Putting the cyclic gesture on a cognitive basis. CogniTextes, 6.

Ladewig, S. H. (2014). The cyclic gesture. In C. Müller, A. Cienki, E. Fricke, S. H. Ladewig, D. McNeill, & J. Bressem (Eds.). Body - language - communication: An international handbook on multimodality in human interaction (Vol. 2, pp. 1605-1618). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter Mouton.

Ladewig, S. H. (2020). Integrating gestures: The dimension of multimodality in cognitive grammar. Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter Mouton.

Ladewig, S. H. (2024). Recurrent gestures: Cultural, individual, and linguistic dimensions of meaning-making. In A. Cienki (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of gesture studies (pp. 32-55). Cambridge University Press.

Lakoff, R. (1973). Language and woman’s place. Language in Society, 2(1), 45-79. doi:10.1017/S0047404500000051

Lempert, M. (2017). Uncommon resemblance: Pragmatic affinity in political gesture. Gesture, 16(1), 35-67. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1075/gest.16.1.02lem

Levinson, S. C. (2013). Action formation and ascription. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.). The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 101-130). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Loehr, D. P. (2007). Aspects of rhythm in gesture and speech. Gesture, 7, 179-214.

Marmorstein, M. (2024). Request for confirmation sequences in Egyptian Arabic. Open Linguistics, 10(1), 20240009. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2024-0009

McIlvenny, P. (2022). Guide for DOTE users. Software documentation, Github Docs. Retrieved from https://bigsoftvideo.github.io/DOTE/

McIlvenny, P. (2024). Guide for DOTEbase Users. Software documentation, Github Docs. Retrieved from https://bigsoftvideo.github.io/DOTEbase/

McNeill, D. (2005). Gesture and thought. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Mithun, M. (2012). Tags: Cross-linguistic diversity and commonality. Journal of Pragmatics, 44(15), 2165-2182. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.09.010

Mondada, L. (2013). Multimodal interaction. In C. Müller, A. Cienki, E. Fricke, S. H. Ladewig, D. McNeill, & S. Tessendorf (Eds.). Body - language - communication (pp. 577-589). De Gruyter Mouton.

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85-106.

Mortensen, K. (2016). The Body as a Resource for Other-Initiation of Repair: Cupping the Hand Behind the Ear. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 49(1), 34-57. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2016.1126450

Murphy, I. (2014). The realization of negation in the Syrian Arabic clause, phrase, and word [Master’s thesis, Trinity College Dublin].

Nota, N., Trujillo, J. P., & Holler, J. (2021). Facial signals and social actions in multimodal face-to-face interaction. Brain Sciences, 11(8), 1017. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11081017

Nota, N., Trujillo, J. P., & Holler, J. (2023). Conversational eyebrow frowns facilitate question identification: An online study using virtual avatars. Cognitive Science, 47(12). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.13392

Novick, D. G., & Sutton, S. (1994). An empirical model of acknowledgment for spoken-language systems. In 32nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (pp. 96-101). Las Cruces, New Mexico, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics.

Oloff, F. (2018). “Sorry?”/”Como?”/”Was?”—Open class and embodied repair initiators in international workplace interactions. J. Pragmat. 126, 29-51.

Pomerantz, A. (1984). Pursuing a response. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.). Structures of social action (pp. 152-164). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Rando, E. (1980). Intonation in discourse. In L. Waugh & C. van Schooneveld (Eds.). The melody of language (pp. 243-278). Baltimore, MD: University Park Press.

Reese, B., & Asher, N. (2007). Prosody and the interpretation of tag questions. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, 11, 448-462.

Rochet-Capellan, A., Laboissière, R., Galván, A., & Schwartz, J. L. (2008). The speech focus position effect on jaw-finger coordination in a pointing task. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51, 1507-1521.

Rohrer, P. (2022). A temporal and pragmatic analysis of gesture-speech association: A corpus-based approach using the novel MultiModal MultiDimensional (M3D) labeling system [Doctoral dissertation, Nantes Université; Universitat Pompeu Fabra]. Retrieved from https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03994053

Rossano, F., Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (2009). Gaze, questioning, and culture. In J. Sidnell (Ed.). Conversation analysis: Comparative perspectives (pp. 187-249). Cambridge University Press.

Ruth-Hirrel, L. (2018). A construction-based approach to cyclic gesture functions in English and Farsi [Doctoral dissertation, University of New Mexico]. University of New Mexico Digital Repository. Retrieved from Retrieved from https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ling_etds/57/

Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures on Conversation. Oxford: Blackwell.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696-735. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.2307/412243

Sadock, J. M. (1974). Toward a Linguistic Theory of Speech Acts. New York: Academic Press.

Sailor, C. (2009). Tagged for deletion: A typological approach to VP ellipsis in tag questions [Master’s thesis, University of California, Los Angeles].

Schegloff, E. A. (1968). Sequencing in conversational openings. American Anthropologist, 70, 1075-1095.

Schegloff, E. A. (1998). Body torque. Social Research, 65(3), 535-586.

Schegloff, E. A. (2000). When ‘others’ initiate repair. Applied Linguistics, 21(2), 205-243. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/21.2.205

Schegloff, E. A., & Sacks, H. (1973). Opening up closings. Semiotica, 8, 289-327.

Schegloff, E. A., Jefferson, G., & Sacks, H. (1977). The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. Language, 53(2), 361-382. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1977.0041

Selting, M. (1998). TCUs and TRPs: The construction of ‘units’ in conversational talk. Interaction and Linguistic Structures, 4, 1-48.

Seo, M.-S., & Koshik, I. (2010). A conversation analytic study of gestures that engender repair in ESL conversational tutoring. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(9), 2219-2239.

Seyfeddinipur, M. (2006). Disfluency: Interrupting speech and gesture [Doctoral dissertation, Radboud University Nijmegen]. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.17617/2.59337

Stivers, T. & Sidnell, J. (2005). Introduction: Multimodal interaction. Semiotica, 2005(156), 1-20. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.2005.2005.156.1

Stivers, T., & Robinson, J.D. (2006). A preference for progressivity in interaction. Language in Society, 35, 367-392.

Stivers, T., Enfield, N. J., Brown, P., Englert, C., Hayashi, M., Heinemann, T., Hoymann, G., Rossano, F., de Ruiter, J. P., Yoon, K. E., & Levinson, S. C. (2009). Universals and cultural variation in turn-taking in conversation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(26), 10587-10592. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0903616106

Stivers, T., & Rossano, F. (2010). Mobilizing response. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 43(1), 3-31. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810903471258

Streeck, J. (2008). Gesture in political communication: A case study of the Democratic presidential candidates during the 2004 primary campaign. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 41(2), 154-186. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810802028662

Stukenbrock, A. (2018). Forward-looking: Where do we go with multimodal projections? In A. Depperman & J. Streeck (Eds.), Time in embodied interaction: Synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resources (pp. 31-68). John Benjamins.

Swerts, M. G. J., & Krahmer, E. J. (2010). Visual prosody of newsreaders: Effects of information structure, emotional content and intended audience on facial expressions. Journal of Phonetics, 38(2), 197-206.

ter Bekke, M., Drijvers, L., & Holler, J. (2024). Hand gestures have predictive potential during conversation: An investigation of the timing of gestures in relation to speech. Cognitive Science, 48(1). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.13407

Tomaselli, M.V., & Gatt, A. (2015). Italian tag questions and their conversational functions. Journal of Pragmatics, 84, 54-82.

Torreira, F., & Valtersson, E. (2015). Phonetic and visual cues to questionhood in French conversation. Phonetica, 72(2), 81-106. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1159/000381723

Tottie, G., & Hoffmann, S. (2006). Tag questions in British and American English. Journal of English Linguistics, 34(4), 283-311.

Tsai, N. (2019). A multimodal analysis of tag questions in Mandarin Chinese multi-party conversation. In X. Li & T. Ono (Eds.). Multimodality in Chinese interaction (pp. 300-332). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

Wagner, P., Malisz, Z., & Kopp, S. (2014). Gesture and speech in interaction: An overview. Speech Communication, 57, 209-232. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2013.09.008

Walker, M. B., & Trimboli, C. (1982). Smooth transitions in conversational interactions. The Journal of Social Psychology, 117(2), 305-306. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1982.9713444

Yang, W. (2015). A study of the interactional function of the tag question Dui Bu Dui in Mandarin conversation from a multimodal perspective [Master’s thesis, University of Alberta].

Appendix A

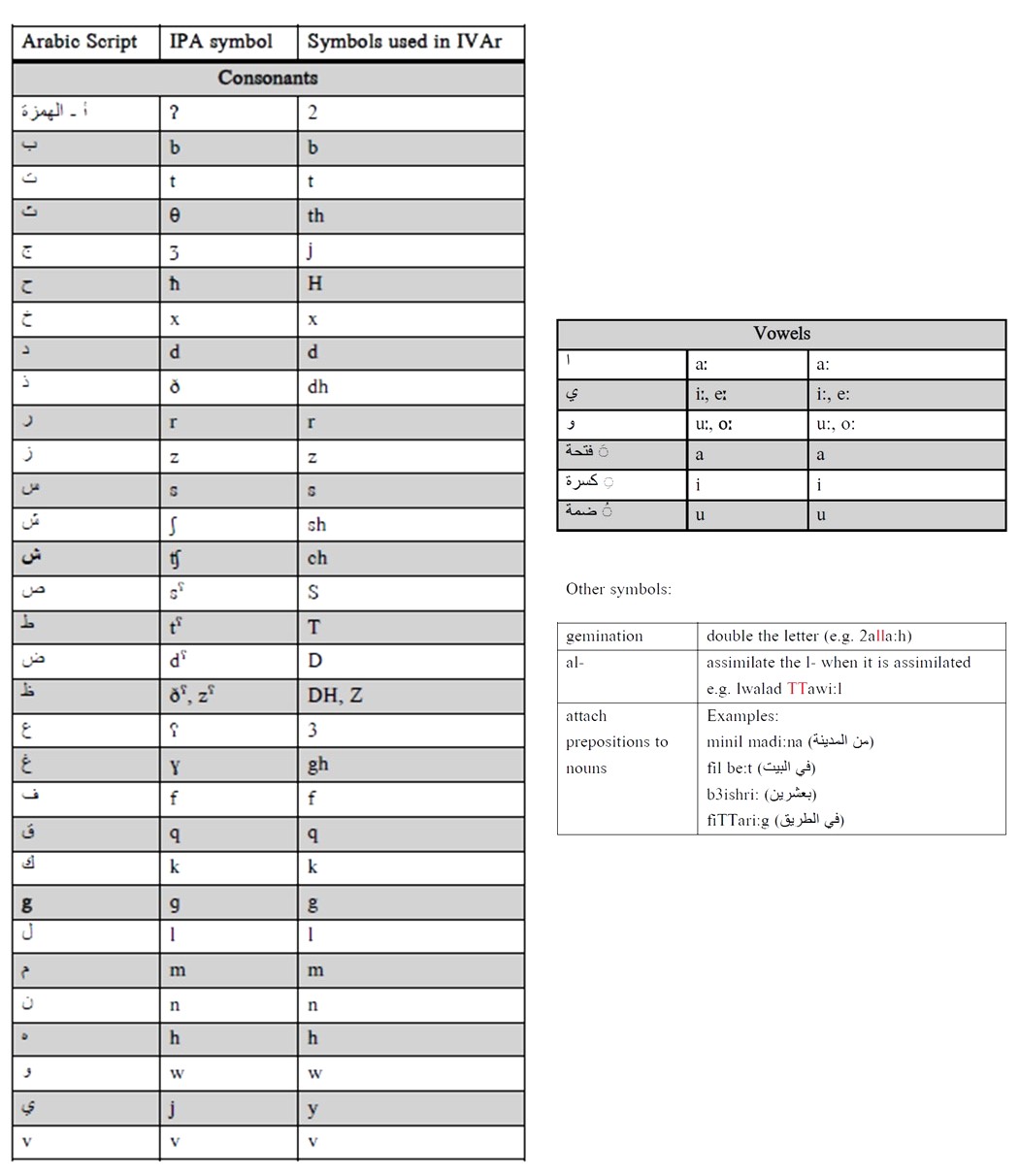

Table 2. IPA symbols for transliterated Arabic script (Hellmuth & Almbark, 2019).

Other symbols:

| gemination | double the letter (e.g. 2alla:h) |

| al- | assimilate the l- when it is assimilated e.g. lwalad TTawi:l |

| attach prepositions to nouns | Examples:

minil madi:na (من المدينة) fil be:t (في البيت) b3ishri: (بعشرين) fiTTari:g (في الطريق) |

Appendix B

Figure 3. A screenshot from the second camera showing the three participants (see Excerpt 4, a chat on the sidewalk - discussing jobs).

1 A question tag (QT) may be referred to as a "tag" in this study for simplicity.↩

2 Research shows the difficulty of transcribing Arabic characters, especially in the non-standardized spoken dialects (Farag, 2019). For transliteration, the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) was used (see Appendix A) with a special character for Arabic long vowels (i.e., the macron diacritic ( ̄ ) to indicate vowel lengthening instead of the colon (:) which indicates extra prolonged vowel or consonant in DOTE, in line with the Jeffersonian conventions).↩

3 For a quick overview of the Jeffersonian transcription conventions, refer to https://universitytranscriptions.co.uk/jefferson-transcription-system-a-guide-to-the-symbols/ For a quick overview of the Mondadian transcription conventions, refer to https://www.lorenzamondada.net/multimodal-transcription ↩

4 In one of the recordings, the speaker nods twice to elicit a response, therefore performing a nonverbal PPQT. The nods are accompanied by a gaze directed toward the addressee and an eyebrow raise in one case. These two cases still need further research.↩

5 The use of arrows to present the sequence of elements follows the work of Jefferson (1981) and Novick & Sutton (1994).↩

6 The participants' names in the excerpts are made up for privacy.↩

7 While multimodally transcribing in DOTE, the following abbreviations are used: eyebrow frown (EBF), eyebrow raise (EBR), gz (gaze), lks (looks), BH (both-hand gesture), RH (right-hand gesture), LH (left-hand gesture), fig (figure).↩

8 Anchor: lines 2 & 3, element preceding the PPQT: line 4, PPQT: line 5.↩

9 While sˤaħ (‘right’) is derived from a verb, originating from the triliteral root (ṣ-ħ-ħ) (Almaany, n.d.), which generally conveys meanings related to correctness, validity, or soundness, its meaning overlaps with the adjective sˤaḥīḥ, meaning "correct" or "true." In its current colloquial form, however, it functions as a discourse marker rather than a verb or adjective. Since it bears no special morphosyntactic marking, TQs with sˤaħ (‘right’) are recognizable only by other means, including their rising intonation.↩

10 Anchor: line 3, element preceding the PPQT: line 3, PPQT: line 5.↩

11 See De Stefani (2021) for a distinction between answer-nods and non-answer-nods (i.e., continuers).↩

12 Anchor: line 4, element preceding the PPQT: line 6, PPQT: line 7.↩

13 According to Couper-Kuhlen and Selting (2017, p. 38), collaborative completions occur when a turn constructional unit (TCU) is begun by one speaker and completed by another or by both speakers simultaneously. The collaborative completion of sentences and/or clauses reveals that the syntactic structures are interactionally shared.↩

14 Anchor: lines 1 & 3, element preceding the PPQT: line 3, PPQT: line 4.↩

15 The interrogativity of sˤaħ willā lāʔ (‘right or not’) in Arabic arises from its syntactic structure and pragmatic context. The coordinating conjunction willā introduces an alternative (negated) possibility. The negation lāʔ reinforces a contrast between the affirmative and negative options. Together, sˤaħ willā lāʔ follows a coordinated disjunctive structure and establishes a binary opposition (Biezma, & Rawlins, 2012; Gómez González & Silvano, 2022).↩

16 First example. Anchor: line 2, element preceding the PPQT: lines 4 & 6, PPQT: line 6. Second example. Anchor: line 11, element preceding the PPQT: lines 13 & 14, PPQT: line 14.↩