Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

A Touch of Companionship:

Supporting Engagement in Dance Activities with People Living with Dementia

An Kosurko1 & Joseph Webb2

1University of Helsinki

2University of Bristol

Abstract

Dance activities are promoted with a range of benefits in institutional settings for people living with dementia (PLWD) and necessitate the active involvement of companions for engagement. This ethnomethodological study uses multimodal conversation analysis to explore how the role of the companion emerges to engage PLWD in dance activities, with special attention on different uses of touch to support engagement in embodied interactions. Analyses of video recordings focus on interactions between companions and PLWD in both structured and unstructured dance activities in institutional settings in Canada, Finland, and the UK. We demonstrate how companions use touch and other multimodal resources to engage participants with others in dance activities. We argue that the role of the companion emerges in interaction and can shift from participant to participant, including PLWD. We conclude with discussion and recommendations for supporting the engagement of PLWD with sensitivity to how actions obligate responses.

Keywords: ethnomethodological conversation analysis (EMCA), multimodality, dementia, dance, engagement, companions

1. Introduction

The role of the companion has become a salient topic of interest over the last decade in conversation analysis (CA), often within healthcare research (see Antaki & Chinn, 2019; Pino, Doehring & Parry, 2021; Chinn, 2022 Laidsaar-Powell, 2013). In these studies, companions have been shown to play an important role in triadic encounters involving practitioners and the subjects of their care, particularly in cases of cognitive asymmetries. The status of 'companion' is often given a priori as the accompanying third-party in the healthcare encounter (spouse, family member, friend, carer). Some research on companions in healthcare interactions has taken a qualitative approach to explore communications and purposes of companions, resulting in various typologies of the role (Laidsaar-Powell, 2013). CA studies have shown how companions' actions, accomplished through talk, are prompted by situated contingencies in sequences of interactions; they respond to needs for assistance in situations that rise out of what was said (or not said) within sequences of turns at talk (Antaki & Chinn, 2019; Pino, Doehring & Parry, 2021). This study takes a similar approach, but in a more creative context, looking at embodied interactions using multimodal CA in dance activities. Based on the traditions of ethnomethodology and conversation analysis (EMCA), we explore how the role of the companion emerges in action multimodally (i.e., through embodiment, use of touch, gaze, as well as talk) towards shared engagement in the context of group dance activities. In the process of our analysis, we came to focus on how different qualities of touch contribute to acts of companionship and how they support engagement of people living with dementia (PLWD) in group dance activities.

We introduce dance into the arena of healthcare interactions as a growing area of interest in aging and dementia care. Social and physical activities like dance are a ubiquitous part of the patchwork of activities organized in care facilities for PLWD; and their companions play an important role in engaging with coparticipants (Skinner et al, 2018; Kontos et al., 2020). Dance activities are often organized and facilitated by staff members, volunteers, and family members who may each take on the role of a companion in different situations. Dance has been widely promoted in dementia care for health, psychosocial and cognitive benefits (Guzmán-García et al., 2013; Mabire et al., 2019). Dementia afflicts cognitive domains such as memory, language, attention, and motor perception, causing deterioration of language systems (Kohlenberg and Kohlenberg, 2021), resulting in the need for assistance from companions in everyday life (Bosco et al., 2019). Engagement is important in the context of dementia care where PLWD may face challenges with maintaining attention, understanding instruction, and communication (Banovic et al., 2018; Kindell et al., 2017; Fernandez-Duque & Black, 2008). This article focuses on how the role of the companion emerges in their actions to engage PLWD in dance activities.

The notions of companionship and engagement are interestingly related to each other in the nature of their 'withness'. While we frame our study around the role of the companion which infers an individual person; there is a plurality in the very nature of companionship, i.e., one may not be a companion without being in company with another. At the same time, being in copresence does not sufficiently define a companion. It is through recognized action that the role of the companion emerges. Importantly, the distinction of companion status is one that is more egalitarian than, for example, an employer and employee - companions exist together "with" each other in various contexts and relationships. Engagement is related to the notion of companionship in that there is a state of connection - bound in or committed somehow - to a moment, to an activity, to a person, etc. In this 'withness', it is the egalitarian nature of the engagement towards doing the act together that makes it one of companionship. From an ethnomethodological perspective, the structure of social order is both created and made sense of by the members of an interaction in progress, in specific situated contexts (Garfinkel, 1984). In studying the role of the companion from this perspective, its constitution must be made accountably relevant by a member of the interaction to become ratified. This accountable relevance of the companion must be visibly displayed or demonstrably understandable as having their engaging actions responded to and resulting in "being with" each other. Using instructed action as an example, an instruction is not recognized as such until it is completed by its recipient (Garfinkel, 1984). In this sense making, it is comprised of two parts: the instruction, and the completion of the instructed action, in CA terms, this is sequentially organized as a first pair part and a second pair part (Schegloff, 2007). An engaging action or an act of companionship may be constituted similarly in first an engaging act or an egalitarian offer; and second, an engagement or an acceptance of the offer on egalitarian terms. Importantly, to draw attention to engagement, a state of nonengagement (or disengagement) is necessary. This is addressed by the property of conditional relevance as described by Schegloff (1968) as, "given the first, the second is expectable; upon its occurrence it can be seen to be a second item to the first; upon its non-occurrence it can be seen to be officially absent—all this provided by the occurrence of the first item (Schegloff, 1968, p. 1083). In our analysis that follows, in the context of the dance activity, the occurrence of the first item is the ongoing dance activity. Companions in their engaging actions, then, address a form of non-engagement. The engaging act can then be a kind of repair initiation, responding to the non-engagement as a 'trouble', for our purposes, in the embodied sense (Lerner and Raymond, 2021).

In their institutional interaction study, Peräkylä and colleagues (2021) describe a continuum of engagement and disengagement inspired by Goffmanian involvement in notions of participation obligations, conjoint visual attention, and situational proprieties (Goffman, 1963). They operationalize the analysis of engagement in CA terms of collaboration in joint action, postural and perceptual orientation, and sharing in the moral order of the encounter. The definition of engagement in their work is onefold: "to show with one's actions and body that one willingly and wholeheartedly takes part in the encounter at hand and focuses one's attention to it and its participants" (Peräkylä et al., 2021). Building along these lines, the aim of our work is to show how companionship emerges and becomes visible in processes of engagement as it is reciprocated and consequentially results in shared dance. The question is, does the companion in their a priori status act in their role to engage PLWD or does the role of the companion emerge in engaging the PLWD? We posit, in the context of the dance activity, that the nature of the engaging action taken by a participant, and how that is recognized by the consequentially engaged recipient in interaction makes visible the companionship that participants hold together. We look at this using multimodal analysis. Therefore, our definition of engagement is two-fold, i.e., it takes 'one's willing action and one's focusing of attention' and a reciprocating of that action and attention to result in a shared connection of companionship.

The constitutive plurality of multimodality infers that the spoken language of talk is one of many modes of conduct and does not take priority over others. This is especially pertinent in analyses of dance activities, where talk is but one of many resources that may be mobilized in the organization of action towards achieving the embodiment of a dance. Multimodality in CA refers to interactants use of many resources such as touch, gaze, body movements, etc., as well as linguistic, (i.e., not prioritizing talk as the dominant mode of conversation) in intertwined ways to organize action (Mondada, 2014b). For example, embodied behaviour can be the first resort in managing a joint activity (Stevanovic & Monzoni, 2016). The resource of touch has been studied extensively in multimodal studies that have demonstrated how it may accomplish and/or contribute to diverse practices and actions in ordered interaction. Touch can be used in establishing joint attention and action (Keel & Caviglia, 2023); in managing turn-taking (Jakonen & Niemi, 2020); professionally in steering focus (Ma et al., 2023); as a summons, directive, or affiliative gesture; in mutual monitoring, and practices to achieve compliance (Cekaite, 2015; Cekaite & Mondada, 2020). Intersubjectivity of touch is achieved by participants locally in interaction and gaze is critical for both public intelligibility and influences the quality of touch (Mondada et al., 2021). Gaze is intrinsically implicated in engagement of touch before it is accomplished, in the emergent reciprocity of a projected arm reach, for example. As part of a multimodal gestalt, touch, along with gaze and deictic pointing gestures, can contribute to directing recipients' attention in pedagogical activities (Routarinne et al., 2020). A third-party gaze as witness to a touching action is significant in how it may produce social or moral meaning. The nature of the touch, its diagnostic, professional, or personal purpose, the situation and environment it is used in, how it is initiated or responded to and by whom, these details make touch recognizable as specific actions. The hand touch has specific qualities and communicative potential that are accountable social situations and between social actors such as affectionate or affiliating touch. Purposes of touch are oriented to by participants in the course of action and the attribution of who has the right to touch may be determined by social roles, situations, and settings. Asymmetries may be accountable in who is in a position to touch whom and how various responses to touch are obligated. Attention has been brought to the inherent reciprocity of touch in that it also involves being touched, but this reciprocity does not inevitably equate to symmetry. More attention could be paid to how reciprocity of touch is organized and in how initiations and responses are designed in ways that are reciprocal or not (see Cekaite and Mondada, 2020).

This article presents a multimodal EMCA study that explores the role of the companion in supporting the engagement of PLWD in dance activities. We focus particular interest on the use of touch as a resource to achieve engagement in the embodied context of the group dance. Our examples show how companions use touch in different ways to initiate the engagement of PLWD and we discuss how these practices obligate responses, as displayed by recipients.

2. Data and Methods

Dance data were collected in three previous studies: "Improving social inclusion for Canadians living with dementia and their carers through Sharing Dance" (Skinner et al., 2018); with an extended study in Finland (see Kosurko et al., 2020); and "Getting Things Changed" in the UK (Williams et al., 2023). The co-authors gathered video footage from those studies that shared the common features of dance activities with PLWD and their various companions (family, volunteer, staff) in institutional, long-term residential care (LTRC) settings. We differentiate in the data between 'staff' and 'staff facilitators' because sometimes staff are a participant in the dance, and at other times they specifically occupy the role of facilitator, leading the activity. For the Sharing Dance program, a facilitator was chosen from the group and could be a staff member or volunteer. The full corpus of data includes 34 hours of video recordings of online chair dance classes for older people who live with dementia in three (3) institutional settings in Canada, two (2) in Finland, and 10 hours in UK of various social care interactions and activities. While each of the three studies were conducted in different countries and for different research purposes, and each of the dance activities were structured differently (i.e., remote vs. co-present instruction or social dancing), the copresence of companions and their actions to support PLWD engagement became a common focus of interest in all settings. Ethics approval was secured in Canada by the Research Ethics Boards at Trent University in Ontario, Canada, and Brandon University in Manitoba, Canada; in Finland by the University of Helsinki Ethical Review Board of Humanities and Social and Behavioural Sciences; in UK by Social Care Research Ethics Committee. Informed consent was sought from all participants and was obtained in cooperation with nursing staff and third-party signing authorities (where appropriate).

The process of our analysis began with unmotivated looking (Sacks, 1984) at dance in general as an activity in three datasets (described above). Using multimodal transcripts in data sessions, we were initially interested in the ways in which PLWD may initiate actions involved in dancing together with other participants in the group activity in both structured and unstructured dance activities. In response to the call for proposals for this special edition on the role of the companion, we shifted our analytical focus to how various caregivers supported PLWD in the dance activities and we narrowed down our collection to 22 examples. We noticed that touch was used to support engagement by companions albeit in different actions, sequences, and combinations of multimodal resources. Video excerpts were chosen where a coparticipant conducted interactional work using touch (among other multimodal resources such as gaze, pointing, bodily movements, and talk) towards the goal of engaging a disengaged or nonengaged PLWD in the group dance activity. In our line-by-line action-interaction analysis (shown below), we identified how the touch was initiated, the nature of the obligation to respond, and how these touching actions were recognized and understood by recipients based on participants' responses. We narrowed our examples to six excerpts that illustrate a variety of ways in which companions drew on multimodal resources including touch to support engagement of PLWD, resulting in shared dance activity. In CA studies, talk is more often the focus of the analysis and looking at a particular phenomenon across a collection of its occurrences in a number of interactional examples. Our study uses multimodal interaction analysis to show several different phenomena in a collection of diverse cases that share a commonality in achieving shared engagement of a dance activity, implicating touch as an interactional resource for engagement.

3. Transcripts

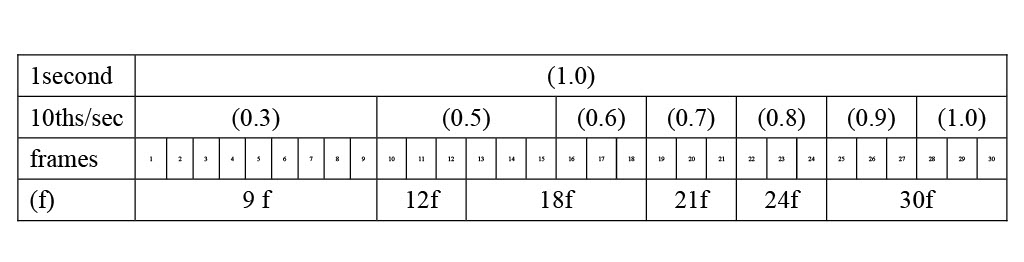

Each example of an engaging interaction below is introduced with a general gloss that describes the situational context and the focus of the interaction, followed by a transcript that annotates all possibly relevant embodied actions following multimodal conventions (Mondada, 2014a), with notations in the talk that follow the system of Jefferson (2004) (see Appendix A). Timing is represented in transcripts in seconds and tenths of seconds that have been converted from frames according to the output settings of QuickTime video application format of 30 frames per second (See Table 1.)

Table 1. Representation of timing in multimodal transcripts of video data, conversion of frames to seconds/tenths of seconds

The sketches included below are anonymized screen captures of moments when companions use touch and are precisely located in time by the symbol # with respect to the relevant line (of talk or timing) of embodied conduct. Following each transcript is a line-by-line action analysis with an analytical summary of the relevance of the example to how the role of the companion emerges through the engaging action in their use of touch.

4. Analysis and Results

The analyses presented below aim to explicate how the role of the companion emerges in action and interaction moment-by-moment in the context of the dance activity and develops sequentially and multimodally, emphasizing touch: first, in the action taken to engage with participants, followed by the recognizable display of the companion that results in dancing together.

4.1 Touch to engage joint attention

In the first example (1), we show how a staff member, as a coparticipant in the dance, uses touch to check in with a participant (Robert) who seems to have fallen asleep during a group dance activity. When Robert opens his eyes and interacts with the staff upon being touched, the staff goes back to participating in the dance and Robert looks to the co-present dance instructor and resumes the activity on his own time. As the sequence begins, Robert is seated between another resident and a staff person whose arms are both raised in participating in the chair dance class. Robert's arms have become still, and his eyes are closed.

Extract 1. Dance Instructor, (dan) (not pictured), Other participant (p) (on left), Robert PLWD (rob) Δ (in middle), Staff (sta) + (on right)

Open in a separate windowThe staff member looks at Robert (1a) (Figure 1) and suspends her own arm movements, reaches to and then gently covers his hand with her own (1a) (Figure 2), using diagnostic touch that checks for sensitivity (Ma et al., 2023), relevant as Robert opens his eyes and looks to staff as source of the touch, his smile displays a non-negative stance on the moment of being wakened (1b). In his next action (reaching into his pocket for a handkerchief), Robert holds the gaze and hand of the staff, (2a) who mirrors Robert with a head tilt and smile, (2b) (Figure 3). As Robert blows his nose, (lines omitted), the Staff shifts their gaze to and aligns their arm movements with another participant's, (6a-c). Four seconds later, Robert looks to the dance instructor, raises his arms in synchronized movements with others (6a). The excerpt closes as all three participants are moving together in the dance, with matching arm movements (Figure 4).

Engagement was projected from the beginning of the sequence when the staff member used touch to check in with Rob (1a-1b). The staff oriented to Rob's noticeably absent engagement as a missing response to a previous, implicit invitation to join the dance. The Staff's action taken to engage Rob using touch was a post-expansion to an already ongoing extended sequence. The soft nature of the touch neutralized any obligation of a response, (i.e., if Rob had fallen asleep, that would have accounted for his disengagement), similar to a pre-invitation, checking the availability of the recipient. The subsequent extended hold of the touch in shared gaze displayed Rob's accepting receipt of the touch in engagement, and the withness of the two participants in a shared moment, ratifying the Staff as companion in that moment. At that point, with the participant engaged in mutual joint attention (Peräkylä et al., 2021), the companion resumed her own participation in the dance, with no further invitation or directive to participate. In this example, Rob was brought into joint attention with others in the activity and he engaged in the dance activity of his own volition, in his own time, in his own way. The result of the interaction was that all participants were engaged in the dance together as a group.

4.2 Touch to connect to synchronous choreography

In the next example (2), we analyse how a staff member uses touch to establish connectedness between coparticipants. In her role, the facilitator is oriented toward the achievement of a shared dance as directed by an on-screen instructor (OSI). Lena and Sue are seated on either side of the staff facilitator, the three of them in a side-by-side arrangement of chairs facing the screen. The OSI provides multimodal directives throughout the excerpt and both Lena and Sue respond with embodied actions of their own individual design. The staff facilitator monitors the participants and joins in with their movements, using touch to connect them together as a group.

Extract 2. On-screen instructor (OSI) (not pictured), PLWD Lena (len) • (on left), PLWD Sue Δ (on right), Staff Facilitator (fac) + (in middle)

Open in a separate windowThe OSI gives a multimodal directive (1, 1a) as Lena and Sue focus on the screen in front of them (1b,1c). Sue moves her fingers but not her feet (1b). Lena moves her foot "out" and "in" as directed (1c). At the same time the facilitator's gaze shifts to Lena's moving foot; she places a hand on Lena's arm (Figure 5); and moves her heel out synchronously (1 d-f), which continues on two alternating feet (2a,b). During these repetitions, the facilitator's gaze shifts first to the screen(1d), then to Sue (2c). The facilitator touches Sue's leg with the tip of her fingers before returning her gaze to the screen (2c). Sue gently taps her foot (2e) synchronously with the facilitator, Lena, and OSI. The excerpt ends with all three participants moving their feet synchronously, while physically connected through the touch of the facilitator (Figure 6).

The connecting touch of the staff brought the participants together in synchronous dance movements in parallel, facing the screen together. In this example, it was the staff who was disengaged from the activity and used touch in mutual monitoring to align with the rhythm of Lena's following of the OSI, looking at Lena's feet, then the screen. Lena's continuation of her leg movements in the dance without responding to the staff's touch displayed her acceptance of the touch without looking for an account. After connecting with Lena and continuing with her synchronous leg movements, the staff used her other hand to touch Sue's leg. The nature of the touch contrasted in its quality and reference point. Using the tips of her fingers, the staff touched Sue's leg, which had not been moving up to that point. Sue responded with foot tapping in alignment with the rhythm of the other participants in the activity. It was Lena's accepting action of the staff's touch in which the companion role was ratified and subsequently shared between them. This afforded the Staff to subsequently connect Sue to the same rhythm, whose response to the leg touch brought the three together in that moment of the dance.

4.3 Assisting with a touch of summons and requests

In the next example, we analyse how a staff member conducts interactional work to facilitate understanding between spouses in the achievement of a shared dance as directed by an on-screen dance instructor (OSI). In Excerpt (3), a visiting spouse (Peter) tries to get his spouse (Sally), a resident PLWD, to follow the instructions of a dance instructor on the screen in front of them. He taps her arm to get her attention and points at the screen, asking her if she can "do it". When Sally doesn't respond, Peter looks to the staff nearby, who, while monitoring participants in her role as facilitator, intervenes to help Sally accomplish the task. Just prior to the beginning of the excerpt, the OSI has directed participants to move their arms outwards as if opening a book. Sally is looking at the screen, her hands in her lap.

Extract 3. Sally (sal): resident PLWD Δ (on left) , Peter (pet) visiting spouse • (in middle), Staff Facilitator (fac) + (on right), On-screen Instructor (osi) © (not pictured)

Open in a separate windowThe sequence begins when Peter's gaze shifts to Sally and he taps her three times on the arm, projecting a relevant possible next for Sally (1a). Sally looks to Peter in response to the tap (1b), making his summons accountable. The Staff's gaze is towards Peter and Sally, accountable as a third-party witness to a touch. She is monitoring the coparticipants in her role as facilitator, while completing the instructed arm movements (1c) (Figure 7). Peter's request "can you do it," (2) again projects a relevant possible next for Sally, based on her ability to complete the action (Curl & Drew, 2008), while at the same time providing an account for his initial summons (1a), orienting to Sally's nonengagement. By pointing to the screen (2a) with his finger and following that with his gaze, Peter's complex multimodal gestalt directs Sally's attention (Routarinne et al., 2020) indexing the OSI as the referent object to which he ascribes "do it." He then moves his own hand in compliance with the OSI (3c). Sally's gaze shifts first to the staff facilitator, who closes her arms (2c) then to the screen (possibly displays her understanding of Peter's deictic gesture), she does not move her hands, making visible an absent embodied second pair part to his first in an initial request (Keevallik, 2018; Schegloff, 2007). Peter looks at the facilitator (3b), making visible the facilitator's monitoring gaze (1c) and potential noticing of Sally's missing response made relevant by the facilitator's next action (5,5a below), that confirms her joint seeing (Haddington et al., 2022) of Sally's noncompliance. Peter resumes his gaze and movements orienting to the OSI (3b,c).

The facilitator's multimodal directive (5,5a) reformulates the OSI's multimodal directive for Sally (i.e., a verbal directive on Line 4 accompanied, on 4a). The facilitator shortens the OSI's verbal directive "can you take one hand and circle" to "can you circle your hand" adding the name token, "Sally" in the design of the turn for Sally's recipiency (5). At the same time, the facilitator extends her arm towards Sally and circles her wrist to demonstrate how the movement is done (5a) in a depictive gesture that supports the verbal request (Lilja et al, 2021). Sally's response to the co-present facilitator displays her understanding that the facilitator is talking to her, with a repair initiator "pardon" that indicates she did not hear the facilitator (6). In her pursuit of a response (Pomerantz, 1984) the facilitator further simplifies the requested action and upgrades her reformulation, dropping the name token, increasing her volume, and adding an indexical "like this" in reference to her own movement. Sally responds at this point (7b) with the compliant, embodied second pair part, circling her wrist (Figure 8). The consequence of the action at the close of the sequence is all three parties moving their hands in the same way at the same time in synchronized participation in the shared dance activity.

In comparison to the previous two examples, this excerpt shows how a compliant response was obligated by a visiting spouse in brokering an embodied understanding of a request. Similar to Example 1, the touch engaged the attention of the disengaged PLWD but the nature of the touch (a triple tap on the arm) set up a response relevance in Sally's reply whose embodied response was a gaze shift in his direction, making an account for his touch relevant. The husband then initiated Sally's response to a request that obligated her based on her ability to complete the request (Curl & Drew, 2008). Her non-response to his next request, "can you do it," was a noticeable absence that potentially did two things: 1. displayed a breach of prosociality (Schegloff, 1996) or 2. revealed an interactional incompetence, the former face threatening to the spouse, the latter threatening the face of Sally. When the husband looked to the staff member, the staff member responded by initiating a series of upgraded requests to Sally, emerging herself in the role of a companion in her action of "being with" both the husband and Sally to assist in the shared understanding of the dance instruction. The upgraded requests of the facilitator made it easier for Sally to comply, while at the same time making the possibility of noncompliance more accountable regarding her capabilities. The non-compliance with the husband's request was also a potentially delicate matter handled by the staff. The staff's action also emerged her in the role of a companion to both parties by conducting facework (Goffman, 1984) that brought everyone together in a withness at the close of the sequence.

4.4 Shepherding touch in trouble on the dancefloor

In the next example (4), we analyse how a staff member brokers shared understanding between another staff member and Pat (a resident PLWD), to coordinate a sequence of dance steps together. Staff 1 uses touch to shepherd Pat, while at the same time using talk to direct Staff 2. As the excerpt begins, the trio is in the process of getting organized. Pat is midstep when Staff 1 holds her back while she directs the future action in coordination with herself and Staff 2.

Extract 4. Staff 2 (st2)* (on left), Piano Player (2nd to left) Pat (resident PLWD) Δ (in middle), Staff 1 (st1) + (on right).

Open in a separate windowThe sequence begins as Staff 1 uses talk to index the group on common ground "here we are now," (1) holding Pat and Staff 2's attention in mutual gaze (1a,d,e). She steps backwards, points at Staff 2 with an indexical nod and a verbal directive, "you stand there" (1b) her hand on Pat's arm (1c) in a shepherding action (Cekaite, 2015) to manage the turn taking of upcoming action (Jakonen & Niemi, 2020). Staff 2 stands still (1d) while Pat steps forward and then stops (1e) both in compliance with Staff 1's multimodal directives (1d). Staff 1 says, "so we go like this," (Figure 9), her "so" acknowledging achievement of the triadic alignment, making it possible to continue, her prosody as slight pitch fall on "like this" (1), projects a future additional directive to follow on line 2 (below) with "and then like this,":

Staff 1 issues the next multimodal directive, verbally continuing from the previous, "and then like this," (2) indexing her shared embodied demonstration of the arm link with Pat, opening her arm to Pat, who displays her understanding by opening her arm and linking with Staff 1 (2a,b) ratifying Staff 2 as an observer of their example, who is projected to follow in the next turn, which she does (3b) in response to Staff 1 extends her arm to link with (3a) (Figure 11).

When Staff 2 accepts Staff 1's arm link (3a,b) and steps around (4a), her projected trajectory is set to move towards Pat, swung by the momentum created in the arm link and stepping action of Staff 1. Staff 2 then extends her arm to Pat, following the example just demonstrated by the companions (2a,b) completing the instructed action of Staff 1, who acknowledges the group dance accomplishment with a verbal marker "that's it" (4b). In each turn, the participants' linked arms afford a mutual monitoring through touch (see Cekaite & Mondada, 2020), appropriate to the dance activity and to support engagement in the progressivity of the weaving dance step. Staff 1 self-initiated the sequence and obligated responses equally from both Pat and Staff 2, drawing on touch, talk, and gaze to direct each of the other two participants in the dance. When Staff 1 orients to Pat as a partner, she becomes recognizable as a companion in the dance. Staff 1's use of talk to direct Staff 2 while using touch to shepherd Pat in the same sequential position makes her role visible as a broker of understanding between the two participants in two different modes. Staff 1's use of the word "we" equalized the status of Pat and Staff 2 who both complete her instructions as she organizes each partner's turn and managed the progressivity of the dance. The result was that all three participants achieve the dance together in embodied engagement.

4.5 Affiliating touch in engaged disaffiliation

The next example (extract 5) showcases a flower-picking scenario as part of the dance. The on-screen instructor (OSI) is demonstrating the movements and directing the group to embody flower picking followed by sharing their bouquet with others. PLWD (Gloria) has indicated that she does not like this activity. A volunteer beside her and the staff facilitator across from her support her choice to not participate while they maintain her engagement of their performance in the activity. Just prior to the excerpt below, the group has finished picking their imaginary flowers and participants are holding their invisible bouquets in clasped hands. Gloria is watching, but not moving.

Extract 5. On-screen instructor (OSI) (not pictured), Gloria (glo) Δ, resident PLWD Δ (on left), Volunteer (vol) • (in middle), Staff Facilitator (fac) + (on right)

Open in a separate windowThe on-screen instructor (OSI) issues a multimodal directive to "give it" (the imaginary bouquet) "to someone" (1). The volunteer looks at and extends her clenched hands to Gloria and holds them there, offering her bouquet, completing the instructed action and inviting a response from Gloria (1a,b). The facilitator also extends her clenched hands towards Gloria and holds them suspended (2a) in an additional embodied offering (Figure 13). Gloria shifts her gaze to the volunteer's outstretched arms first before turning her head completely (2b) to gain eye contact, which she holds with her for a full second (2b-3), not looking at either bouquet. Gloria then closes her eyes and shakes her head with a grin (3a), displaying her refusal, with a stance display that marks the moment as non-serious (3b) which continues beyond the end of the excerpt (3a). The volunteer and facilitator laugh, dropping their extended arms at the same time (3b-e) while the volunteer caresses Gloria's arm in a manner that physically connects them in a softening of their laughter as laughing "with", not at.

Using the next-turn proof procedure (Sacks et al., 1974), the volunteer and facilitator together treat Gloria's headshake and closed eyes as a laughable, ratifying her action as the punchline of their collaborative joke and effectively sanctioning her choice to not respond to the make-believe sequence. Gloria's head shake and grin continue beyond the end of the excerpt (3a) in maintaining ongoing involvement in the joke. The volunteer emerges as companion when she caresses Gloria's arm with the back of her fingers twice in an affectionate manner using affiliative touch (Cekaite & Mondada, 2020), emphasizing their laughter as non-hostile, connecting to Gloria physically and to the facilitator in laughter. The result is the three dancers connected through the volunteer - using touch on the one side and in laughter with the facilitator in a shared performance of their own.

4.6 Touch in turns to move together and move apart together

In the final example (6), we return to Pat, a PLWD and two social care workers (as seen in extract 3) to show how the role of the companion shifts the participation framework in response to trouble on the dance floor and how each participant takes the role of the companion in turns. A musician at the keyboard provides the musical accompaniment to the dancers, and when he speeds up the rhythm of the music, the shared rhythm and coordination of the dance is lost.

Extract 6. Piano Player (pia), Music (mus) ♫ (right), Pat (on left) Δ, Dave (dav) +, Staff 2 (st2) * (middle), Staff 1 (st1) + (on right)

Open in a separate windowAt the beginning of the sequence, the musician indexes a new challenge to the dancers (1) by increasing the rhythmic pace of the song (1a). Reducing the time in which to move constrained the dancers' shared ability to coordinate. As a result, the dancers cover less distance and share closer proximity to each other in the interactional space. Pat does not have enough time to switch arms, so she offers the "wrong arm" to Staff 2, who brushes past it with her extended arm to link with the "correct arm" (2a) (Figure 15). Her brushing past the incorrect arm causes Pat to lower the "wrong arm" (2c) and then to step through the space left between the two staff members.

Staff 1 links Pat's R arm (2a) and Pat is "stuck" between the two staff members, who both release her arms (3a,b). Pat turns around, her gaze first to Staff 2, who steps back (out of the image above) and claps to the beat in place (3a). Staff 2 responds to the change in rhythm by moving her body back from the other participants and clapping rhythmically in place, changing the participation framework (Goffman, 1981) from an ensemble to individually based. Pat then looks to Staff 1, who alternates her arms in a marching fashion while dancing on the spot, marking her arms as unavailable for further arm linking (3b) (Figure 16). Pat maintains her gaze with Staff 1 and follows her lead in moving her arms and dancing on the spot (3c). Staff 1 breaks her gaze with Pat and looks at her own feet (4b), clapping her hands as she orients to dancing as a single individual. The three are connected in the shared interactional space of the dance floor, with their bodies facing each other, moving to the shared rhythm set by the piano player and timing provided by the music.

At the point where Staff 1 shifts her gaze to her own feet (4a), Pat shifts her gaze to another PLWD, Dave, who is not engaged in the dance activity. Pat walks towards Dave (4c) (Figure 17).

Pat extends her hands towards Dave (5a), who walks towards Pat and extends his arms toward her (5b) treating her outstretched arms as an invitation (Figure 18a). Pat grasps Dave's hand at the same time that Dave grasps Pat's hands (Figure 18b), at which point they are engaged in the dance together with others on the dancefloor. Pat's role as a companion emerged from this space where she self-selected and drew on embodied resources, reaching out to initiate the engagement of an additional participant, inviting Dave to engage in the dance (5a) (Figure 18b). In Dave's reciprocal reach and their mutual hand-grasping, the embodied resources of each become shared in physical connection toward dancing together.

In the final example above, the role of the companion emerged sequentially in the actions of each of three participants who responded to another participant's disengagement from the ongoing activity. The first, a rejection of a projected arm reach caused an adjusting action in response to body trouble (Lerner and Raymond, 2021) when Pat offered the wrong arm to Staff 2, whose touch corrected the arm link, and hence positioned her as a companion that reengages Pat into the dance; the second, the release of both Staff 1 and Staff 2's arm links led to Pat's turn on the spot followed by her searching gaze for an account, to which Staff 1 displayed a shift to dancing as a single individual in her bodily movements, shifting gaze down with clapping, (a self-touch that marked her arms as unavailable for further linking). Staff 1's role as a companion emerged through this displayed sequence of embodied actions. This led to the third emergence of the role of the companion, this time enacted by one of the PLWD, when Pat's gaze shifted to another participant who was not engaged in the dance, and offered her reaching hand, which was accepted in a mutual grasp to join in the dance.

5. Concluding Discussion

Presented above is a selection of six examples in transcripts and multimodal line-by- line action analyses. We demonstrated how the role of the companion emerged through participants' actions to address another participant's absence of withness or engagement in dance activities in the institutional setting. In each example, the absence of a participant's engagement presented itself in different ways and touch was implicated in the companionable action towards engagement. In disengagement from joint attention (example 1), the touching action engaged joint attention in a non-obligating manner. In the staff's missing alignment with the choreography, her touch aligned her with a coparticipant's rhythm (example 2). In a missing response to a request following a husband's touch (example 3), the gaze in the witness led to multimodal instructed action that brought participants together. In troubled coordination of choreography and music, (examples 4 and 6), shepherding touch in sequential turns coordinated joint action and transitions to the next phases of participation. In disaffiliation with stance on participation (example 5), touch was used to affiliate with the participant's stance, marking their nonengagement as allowable. In every example, the role of the companion emerged when a participant initiated an engaging sequence that: a❩ oriented to the absence of another participant's withness; and b❩ took action to engage the participant, with varying responses; c❩ consequentially resulting in withness in the shared activity of the group. Our analysis explicated the engaging actions in multimodal terms, with embodiment being a privileged mode in the context of the dance activity. Each of our examples focused on how touch was implicated in diverse ways (together with gaze, talk, and body movements) to support engagement actions. The consequence of each of the engaging actions was realized as members engaged together with the group in the activity.

As we noted earlier, the accountable relevance of the companion must be visibly displayed or demonstrably understood in terms of egalitarian withness. Evidence of asymmetry, however, may be present in the nature of the obligated response. In each of our examples, actions supported recipients to engage in the shared activity in ways that constrained their choice to respond. That Rob eventually joined in the dance of his own volition (example 1) indicates that he was not obligated to do so because of the touch of the staff to whom he opened his eyes. His engagement in joint attention to the activity provided sufficient opportunity for him to choose to participate. In example 2, in Lena's continued stepping to the beat, the staff was supported to align with her rhythm through her arm touch, thus ratifying the companions in synchronicity. The staff in this case self-selected as having the right to touch both Lena and Sue, which both allowed, however Lena's obligation to do so would have been high because any rejection would disrupt her own and others' ability to maintain alignment with the ongoing activity.

In Example 3, the role of the companion emerged through explicit instructions that assisted Sally to comply with her husband's request. In this case, Sally was doubly obligated to respond to both "companions" in sequentially upgraded requests that were based on her ability to complete the instructed action. In this example, the role of the companion shifted in the actions of each of the spouse and of the facilitator, and the shared companionship operated in two relationships at the same time. In Example 4, both participants were equally obligated to comply in sequence, in order to proceed in the choreography of the dance. While the initial touch of companionship came from Staff 1, Pat was also ratified as a companion in the shared display exemplifying the correct dance moves together for Staff 2.

When the projected expectation of the recipient was one of non-compliance (example 5), two companions maintained the engagement through affiliation with a participant's stance to not participate. Together the companions displayed their shared stance with Gloria who accepted the volunteer's affiliative touch of laughing "with". When the structure of the activity was jointly accomplished in an informal dance activity (example 6), each participant had equal status to initiate the next action and to self select in supporting a fellow dancer in their engagement with the dance. Participants were equally obligated because the progressivity of the action was collaboratively coordinated from moment to moment.

In varying asymmetries of obligation, companions in our definition are recognized as such by participants when they emerge in interaction, not a priori to it. The role, then, manifests in the evidence of their action. In our examples, companions become such through their engaging actions in the service of the overarching activity of (or sub-activities within) dance in institutional settings. The different ways that touch was used in actions that consequentially resulted in withness in the dance help us to think about rights to touch, rights to engage, and how these practices may obligate PLWD socially. Together our examples illustrated how companions' actions obligate responses in various ways, constraining participants' choices to engage with others in dance activities. We have also demonstrated that the role of the companion may shift from participant to participant, be shared by more than one participant, and be oriented to companionship with more than one participant at a time, including in how PLWD themselves can emerge as companions and shape the course of action. Companions in their actions treat themselves as responsive to others in supporting engagement in a number of ways. A crucial distinction between this study and past research on companions is that it focuses on the role of companions in a primarily embodied activity, and in situations where the boundaries of roles are not so prescribed, as, arguably they have been in previous studies of healthcare encounters. Companionship in action requires a sensitivity to how a person is responding moment-to-moment. We recommend a sensitivity to the obligating nature of engaging actions in supporting PLWD. These may well serve to support the choice of the PLWD when they are designed in egalitarian ways in which companionship is held together. Further to this, in supporting PLWD in engagement in any activity, we recommend attentiveness and reciprocity to how PLWD, as they take on the role of the companion, may initiate and support the engagement of others.

References

Antaki, C., & Chinn, D. (2019). Companions' dilemma of intervention when they mediate between patients with intellectual disabilities and health staff. Patient education and counseling, 102(11), 2024-2030.

Laidsaar-Powell, R. C., Butow, P. N., Bu, S., Charles, C., Gafni, A., Lam, W. W., ... & Juraskova, I. (2013). Physician-patient-companion communication and decision-making: a systematic review of triadic medical consultations. Patient education and counseling, 91(1), 3-13.

Banovic, S., Zunic, L. J., & Sinanovic, O. (2018). Communication difficulties as a result of dementia. Materia socio-medica, 30(3), 221.

Cekaite, A. (2015). The coordination of talk and touch in adults' directives to children: Touch and social control. Research on language and social interaction, 48(2), 152-175.

Cekaite, A., & Mondada, L. (Eds.). (2020). Touch in social interaction: Touch, language, and body. Routledge.

Chinn, D. (2022). 'I Have to Explain to him': How Companions Broker Mutual Understanding Between Patients with Intellectual Disabilities and Health Care Practitioners in Primary Care. Qualitative Health Research, 32(8-9), 1215-1229.

Curl, T. & Drew, P. (2008) 'Contingency and Action: A Comparison of Two Forms of Requesting', Research on Language and Social Interaction 41(2): 129-53.

Ekberg, K., Meyer, C., Scarinci, N., Grenness, C., & Hickson, L. (2015). Family member involvement in audiology appointments with older people with hearing impairment. International Journal of Audiology, 54(2), 70-76.

Fernandez-Duque, D., & Black, S. E. (2008). Selective attention in early dementia of Alzheimer type. Brain and Cognition, 66(3), 221-231.

Garfinkel, Harold. (1984). Studies in Ethnomethodology. Malden: Polity Press Malden. First published 1967.

Goffman, E. 1981. Forms of talk. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Goffman, E. 1963. Behavior in Public Places: Notes on the Social Organization of Gatherings. New York, NY: Free Press.

Guzmán-García, A., Hughes, J. C., James, I. A. & Rochester, L. (2013). Dancing as a psychosocial intervention in care homes: a systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28, 914-924.

Haddington, P., Kamunen, A., & Rautiainen, I. (2022). Noticing, monitoring, and observing: Interactional grounds for joint and emergent seeing in UN military observer training. Journal of Pragmatics, 200, 119-138.

Jakonen, T., & Niemi, K. (2020). Managing participation and turn-taking in children's digital activities: Touch in blocking a peer's hand. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 3(1).

Keel, S., & Caviglia, C. (2023). Touching and being touched during physiotherapy exercise instruction. Human Studies, 46(4), 679-699.

Keevallik, L. (2018). What does embodied interaction tell us about grammar?. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 1-21.

Kindell, J., Keady, J., Sage, K., & Wilkinson, R. (2017). Everyday conversation in dementia: A review of the literature to inform research and practice. International journal of language & communication disorders, 52(4), 392-406.

Kohlenberg, C. J., & Kohlenberg, N. J. (2020). Dementia, Etiologies, and Implications on Communication. Learning from the Talk of Persons with Dementia: A Practical Guide to Interaction and Interactional Research, 15-30.

Kontos, P., Grigorovich, A., Kosurko, A., Bar, R., Herron, R., Menec, V., & Skinner, M. (2020). Dancing with dementia: Exploring the embodied dimensions of creativity and social engagement. The Gerontologist 61: 714-23.

Kosurko, A., Arminen, I., Herron, R., Skinner, M., & Stevanovic, M. (2021, July). Observing social connectedness in a digital dance program for older adults: An EMCA approach. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 393-404). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Landmark, A. M. D., Nilsson, E., Ekström, A., & Svennevig, J. (2021). Couples living with dementia managing conflicting knowledge claims. Discourse Studies, 23(2), 191-212.

Lerner, G. H., & Raymond, G. (2021). Body trouble: Some sources of difficulty in the progressive realization of manual action. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 54(3), 277-298.

Lilja, Niina, & Arja Piirainen-Marsh. (2022). Recipient Design by Gestures: How Depictive Gestures Embody Actions in Cooking Instructions. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 5: 1-30.

Ma, W., Zhang, S., Cheng, M., & Liu, H. (2023). Configuring the Professional Touch in Physical Examinations in Chinese Outpatient Clinical Interaction: Talk, Touch, Professional Vision, and Intersubjectivity. Health Communication, 1-16.

Mabire, J. B., Aquino, J. P., & Charras, K. (2019). Dance interventions for people with dementia: systematic review and practice recommendations. International psychogeriatrics, 31(7), 977-987.

Mondada, L. (2014a). Conventions for multimodal transcription.

Mondada, L. (2014b). The local constitution of multimodal resources for social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 65, 137-156.

Mondada, L., Bouaouina, S. A., Camus, L., Gauthier, G., Svensson, H., & Tekin, B. S. (2021). The local and filmed accountability of sensorial practices: The intersubjectivity of touch as an interactional achievement. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 4(3), 30.

O'Brien, R., Beeke, S., Pilnick, A., Goldberg, S. E., & Harwood, R. H. (2020). When people living with dementia say 'no': Negotiating refusal in the acute hospital setting. Social Science & Medicine, 263, 113-188.

Pino, M., Doehring, A., & Parry, R. (2021). Practitioners' dilemmas and strategies in decision-making conversations where patients and companions take divergent positions on a healthcare measure: an observational study using conversation analysis. Health Communication, 36(14), 2010-2021.

Peräkylä, A., Voutilainen, L., Lehtinen, M., & Wuolio, M. (2021). From engagement to disengagement in a psychiatric assessment process. Symbolic Interaction, 45(2), 257-296. https://doi.org/10.1002/symb.574

Pomerantz, A. (1984). Pursuing a response. Structures of social action, 152-166.

Routarinne, S., Heinonen, P., Karvonen, U., Tainio, L., & Ahlholm, M. (2020). Touch in achieving a pedagogically relevant focus in classrooms. Social interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality.

Sacks, H. (1984). Notes on methodology. Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis, 21-27.

Sacks, Harvey, Emanuel A. Schegloff, and Gail van Jefferson. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organisation of turn-taking in conversation. Language, 50, 696-735.

Schegloff, E. A. (1968). Sequencing in conversational openings. American Anthropologist, 70, 1075-1095.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. (2007). Sequence Organization in Interaction: A Primer in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Skinner, Mark W., Rachel V. Herron, Rachel J. Bar, Pia Kontos, & Verena Menec. (2018). Improving social inclusion for people with dementia and carers through sharing dance: A qualitative sequential continuum of care pilot study protocol. BMJ Open 8: E026912.

Stevanovic, M., & Monzoni, C. (2016). On the hierarchy of interactional resources: Embodied and verbal behavior in the management of joint activities with material objects. Journal of Pragmatics, 103, 15-32.

Williams, V., Gall, M., Mason-Angelow, V., Read, S., & Webb, J. (2023). Misfitting and social practice theory: incorporating disability into the performance and (re) enactment of social practices. Disability & society, 38(5), 776-797

Zeiler, K. (2014). A philosophical defense of the idea that we can hold each other in personhood: Intercorporeal personhood in dementia care. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 17(1), 131-141.

Appendix A: Transcript Conventions

Talk was transcribed according to conventions developed by Gail Jefferson (2004) (see, e.g., Schegloff 2007 for a full description).

| gz | gaze |

| ( ) | unheard or unclear utterance[ ] overlapping speech |

| (.) | just noticeable pause |

| (1.0) | timed pauses |

| , | slight rise of intonation in the last syllable |

| (( )) | transcriber's comments or descriptions. |

| wo:rd | colons show that the speaker has stretched the preceding sound |

| word | underlined sounds are louder, capitals louder still |

| = | no discernible pause between two speakers' turns |

Embodied and multimodal actions were transcribed according to the following conventions developed by Lorenza Mondada:

https://www.lorenzamondada.net/multimodal-transcription

| * * | Descriptions of embodied actions are delimited between |

| + + | two identical symbols (one symbol per participant and per type of action) |

| Δ Δ | that are synchronized with correspondent stretches of talk or time. |

| *---> | The action described continues across subsequent lines |

| ---->* | until the same symbol is reached. |

| >> | The action described begins before the excerpts beginning. |

| --->> | The action described continues after the excerpts end. |

| . . . .. | action's preparation |

| ---- | action's apex is reached and maintained |

| „„, | actions retraction |

| ric | participant doing the embodied action is identified in small caps in the margin. |

| fig | The exact moment at which a screen shot has been taken |

| # | is indicated with a sign (#) showing its position within the turn/a time measure. |

| ♫ | delimits musical actions |