Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Geomorphopoetic Vocalisations:

How the Materiality of the Ground Provides Semiotic Structure in

Mountain-bike Crashes

Stina Ericsson & Inga-Lill Grahn

University of Gothenburg

Abstract

Vocalisations - that is, sounds such as oh! or aaah - are highly versatile, obtaining their interactional meaning from the local environment. This study adds to previous research on vocalisations by showing how participants in video clips of mountain-bike crashes interpret the materiality of the ground in meaningful ways using such sounds. The vocalisations are called geomorphopoetic because they imitate the shape of the ground during movement. Three groups of geomorphopoetic vocalisations are identified: (1) sounds that inhabit the evenness and elongation of the ground, (2) sounds that inhabit the smallness of the ground, and (3) sounds that inhabit repeated movements supported by the properties of the ground.

Keywords: vocalisations, multimodal interaction analysis, mountain biking, materiality, semiotic structure

1. Introduction

Vocalisations - sounds such as oh!, oops! or aaah - have highly variable functions in social interaction and can be precisely adjusted to their local environment (Keevallik & Ogden, 2020). Aspects of this local environment identified in recent research include what participants are doing and experiencing, what participants are instructed to do, what tools participants are using, how long embodied actions last and how much effort is needed to perform an action (Grahn et al., 2023; Hofstetter, 2020; Keevallik, 2014; Keevallik et al., 2023; Keevallik & Ogden, 2020; Rohman Roth, 2022; Weatherall et al., 2021). This article explores yet another aspect: movement in relation to the ground, with the ground providing a crucial sense-making materiality to the interaction. Specifically, the ground investigated here is the mountain-bike trail and the movement is that of riders and their bikes when they crash.

Mountain biking is a highly social activity (Cherrington, 2024; Lloyd, 2019). Far from just being a matter for the cyclist and their own body, it is an activity that is frequently shared with other riders and spectators who are physically co-present, and it is often also documented on camera and shared online. That is, mountain biking is also displayed to someone else and recordings are made for a viewer - including the riders themselves. One salient aspect of this social activity is the mountain-bike crash: a rider losing control of their bike and eventually ending up on the ground. As will be seen in this article, vocalisations form an integral part of the social interaction taking place during such crashes, with riders and spectators using vocalisations that convey how they interpret the unfolding mountain-bike crash.

The aim of the article is to identify ways in which the ground - here specifically the mountain-bike trail - and movement combine to provide meaning to the action of bike riding, as evidenced through vocalisations. The vocalisations of riders and spectators in these settings will be referred to as geomorphopoetic1 vocalisations, that is, as sounds that imitate (poetic) the shape (morpho) of the ground (geo) during movement. Examples include an ooooooh produced as a rider moves straight forward along level ground, in contrast to an uh uh uh accompanying a bumpy ride across rocks. These geomorphopoetic vocalisations can be said to inhabit the particularities of a specific portion of the ground across which the rider moves, and it should be noted that the ground in the form of a mountain-bike trail will here be seen to include all types of materialities that riders move across - gravel paths, woodland paths, rocks, wooden constructions, and also air.

The article contributes to the rapidly developing field of vocalisations in interaction, and also to the analysis of interaction more generally, by investigating the materiality of the ground as a meaning-making resource in social interaction.

2. Vocalisations

Vocalisations are highly versatile and flexible in terms of their functions in interaction, their phonology and their relationship with the human bodies that produce them. In and of themselves, vocalisations are semantically underspecified (Deemter & Peters, 1996; Keevallik & Ogden, 2020). Hence they rely on contextual clues for their generation and interpretation, not unlike the kind of short linguistic material sometimes known as elliptical utterances or discourse fragments, which also need context to be fully made sense of (Ericsson, 2005; Schlangen, 2003). For example, such vocalisation-relevant contextual clues - or resources for meaning-making - have been found to include sequential position, iconicity and indexicality, timing and co-ordination in relation to bodies and linguistic features, materiality, and spatiality (Keevallik & Ogden, 2020). It has been shown that, if full account is taken of their context, vocalisations may have quite precise meanings and perform highly specific functions (see also Dingemanse, 2020, p. 191).

In the case of vocalisations produced during mountain-bike crashes, we have identified the following aspects as particularly relevant: embodiment, temporality, prosody and voice quality, and shared emotions and perspectives. They are each described below.

2.1 Embodiment

Vocalisations emanate from a body. This seemingly trivial observation means that vocalisations are shaped and constrained by the body and its doings. A relaxed body can produce other sounds than a strained body, and a highly strained or cognitively occupied body may not be able to produce any sounds at all. For instance, Keevallik and Ogden (2020) argue that a strain grunt produced by a person while lifting a heavy forkful of manure is dependent upon a substantial abdominal push that is also required for the lifting movement, and Grahn et al. (2023) show how series of vocalisations in gym settings are affected by the amount of effort that vocalisers put into their exercising. Similarly, Hofstetter et al. (2021) show how talk is suspended during a turn construction unit (TCU) while a climber is carrying out a strenuous bodily movement, indicating that it is not always possible to strain the body and produce talk (or vocalisations) at the same time.

Another aspect of embodiment is that vocalisations and other bodily actions can constitute a TCU on their own or form part of a TCU together with speech (Keevallik, 2014; Reber & Couper-Kuhlen, 2020). Put differently, vocalisations "are accountable and recognizable indices of bodily events" (Keevallik et al., 2023, p. 13).

2.2 Temporality

The sequential position of vocalisations is one of the resources available for meaning-making that concern temporality. For instance, sniffs have been shown to have varying functions depending on their sequential position: a sniff produced before or during a turn-at-talk can have the function of delaying turn progression, whereas a sniff at the completion of a turn can have the function of indicating that completion (Hoey, 2020). Sniffs have also been shown to preface aroma descriptions, function as confirmation of a previous description or introduce an alternative one (Mondada, 2020). It has also been shown how a doctor's vocalisation of a patient's pain occurs immediately after the patient's display of pain, and how a dance teacher's vocalisation of strain occurs at the precise moment when the dance students are expected to perform a strenuous movement (Keevallik et al., 2023; Weatherall et al., 2021). In general, vocalisations typically seem to convey the "immediacy of something that the body is undergoing" (Keevallik & Ogden, 2020, p. 11) and seem to be timed and co-ordinated with embodied actions (M. H. Goodwin et al., 2012; Keevallik & Ogden, 2020).

The issue of timing may significantly concern not only the start of a vocalisation, but also its end. For example, Keevallik and Ogden (2020) show that the strain grunt produced during the lifting of a heavy forkful of manure is timed with the abdominal push required for both the lifting and the vocalisation. However, they also note that the grunt ends before the spade movement, and they argue that - in the local context that they are analysing - this difference in timing indicates that the strain grunt has a communicative function rather than constituting a physiological necessity. Hence both the beginning and the end of a vocalisation can be relevant to meaning-making.

Other relevant temporal aspects are tempo and duration: vocalisations and talk can be either sped up or slowed down to co-occur with bodily movements (Hofstetter & Keevallik, 2023), and individual sounds can be lengthened to match bodily movements (C. Goodwin, 1979; Hofstetter & Keevallik, 2023; Mondada, 2018a). It is worth noting that the duration aspect places constraints on phonetic selection: vowels and nasals can be lengthened, but stops cannot (M. H. Goodwin et al., 2012).

Timing, tempo and duration can all help vocalisations add rhythm to the shaping of actions. For example, Albert and vom Lehn (2023) show how a novice dancer uses two consecutive and softly vocalised e:hm: and e:hem to co-ordinate his and his dance partner's moves, the two vocalisations being timed with the raising and lowering of their hands. Such vocalised repetitions have been shown to be part of the rhythm of dance in other instructional settings, with Keevallik and Ogden (2020, p. 13) analysing a dance teacher's ZAP pum pum pum pa pu ?a ?u ?a. Based on variation in sounds across several examples, they show that what carries meaning is the rhythm given by the repetition of various sounds, not the individual sounds. In a general way, repetition of both non-lexical and lexical items can be used to organise segments of action (Keevallik et al., 2024).

Repetition has also been shown to play an important role in settings involving strong physical effort. For instance, repetition in the form of serial vocalisations - specifically strain grunts and audible breaths during gym training - has been shown to be meaningful through the way in which changes to such serial vocalisations are treated by participants as accountable (Grahn et al., 2023). Further, the repetition of lexical items can also be used as incitement, for instance the cmo:n cmo:n cmon cmo:n ↑cmo::n! produced by an onlooker while another powerlifter is beginning a bench-press set by pushing the barbell upwards (Reynolds, 2017).

2.3 Prosody and voice quality

Prosody and voice quality can be employed for meaning-making of vocalisations in varying ways. Some non-lexical prosodical features carry conventionalised meanings. For example, Reber and Couper-Kuhlen (2020) show how certain non-melodic whistles have constant and recognisable forms and functions: a tonal whistle is used for summoning and a gliding whistle is used in response to news received. However, vocalisations seem predominantly to obtain their meaning in highly localised contexts.

Variation in the prosody of vocalisations can be used to convey the intensity, sharpness or severity of an embodied experience (Keevallik et al., 2023). For example, loudness can be used to embody strain (Hofstetter & Keevallik, 2023), such as when a dance teacher instructs students to exert themselves through louder and lengthened sounds but makes shorter, quieter and more relaxed sounds to make them perform other movements (Keevallik et al., 2023). Pitch movement, such as an up/down contour, can function as a recognisable pattern during instructions in a Pilates class (Hofstetter & Keevallik, 2023). The up/down pitch contour in question accompanies different bodily movements rather than one specific type of movement. Its function is to co-inhabit moving bodies and to break down a complex exercise into smaller steps. Similarly, Huhtamäki and Grahn (2022) show how assessment-pitch contours mark the transition from one activity to another. Finally, voice quality, such as a strained voice to embody strain (Hofstetter & Keevallik, 2023), can also be used to give vocalisations meaning.

2.4 Shared emotions and perspectives

Studies of emotions in interactional settings have shown how emotions are jointly constructed, are ascribed social meaning and are tied to sequential organisation (Sorjonen & Peräkylä, 2012; Weatherall & Robles, 2021). Such interactional research has convincingly argued that expressions of emotions, such as cries of pain, are often social and interactional in nature and do not simply constitute automatic reflections of an individual's internal state (M. H. Goodwin et al., 2012; Keevallik & Ogden, 2020). What is more, once an expression of emotion has been uttered, it may project ensuing embodied actions by all participants. For example, Goffman (1978) characterises a pain cry such as Oww! or Ouch! in a dentist's chair as a warning from the patient that something has begun to hurt. In other words, the pain cry is not a mere expression of an emotion but provides "a reading for the instigator of the pain" (Goffman, 1978, p. 804).

It is clear from the above that using vocalisations can be a way to take someone else's perspective in an interaction, thereby achieving joint action. Vocalisations can be used to create a sequential slot for "feeling the same", that is, for a jointly felt or witnessed physical experience, as Pehkonen (2020) demonstrates for the Finnish huh huh. Keevallik et al. (2023) explore this phenomenon, which they label "sounding for others", showing that a doctor's uuuw sounds a patient's pain during an examination, that a dance teacher's KRRhahhh and QUOO sound the dancers' strain, and that a mother's lip-smacks and mmmmmmm sound her infant's tasting. The doctor's sounding can be seen as an empathetic acknowledgement whereas the dance teacher's sounding acts as an instruction; the mother's sounding may have elements of both. Grahn et al. (2023) show how a personal trainer co-constructs serial vocalisations with the person who is exercising; this is considered to represent a kind of instruction and is explained in terms of professional vision (C. Goodwin, 2018).

Sounding for others is fundamentally about co-participation and about "participants' displayed sense-making of each other's behavior" (Keevallik et al., 2023, p. 4). This means that the person vocalising another's ongoing experience is "not /…/ an onlooker, but /…/ a coproducer of that very experience" (Keevallik et al., 2023, pp. 13-14). In the case of the mountain bike crash we will show how the vocalisations of riders and spectators coproduce the crash.

3. The actions and semiotic resources of mountain biking

The theoretical starting point of this article is Goodwin's assertion that "material structure in the surround /…/ can provide semiotic structure" (C. Goodwin, 2018, p. 170), that is, that the physical environment can provide meaningful material necessary for "the building of action that could not exist without it" (C. Goodwin, 2018, p. 172). Like the hopscotch grid that Goodwin uses to illustrate his argument, and unlike speech and gestures, the mountain-bike trail is a corporeal, solid and permanent semiotic structure. The material structure of the hopscotch grid is an element in the building of actions such as failed or successful jumps, outs and fouls. In the case of the mountain-bike trail, the material structure is similarly an element in the building of actions such as failed or successful jumps and drops. The materiality of the trail is visibly structured by human action even when no biking is taking place: it can be evidenced by paths that have been cleared or dug, wooden constructions for drops, mounds built for jumps, and the tyre tracks left by hundreds of riders. However, the activity of mountain biking can also take place in an environment previously unstructured by human (mountain-biking) practice, in which case the material structure in the surround builds up as the biking occurs.

In order for action to occur, the embodiment of a material structure is needed. In the case of mountain biking, this embodiment takes the form of a rider acting together with a bike, which also provides material structure. In the video recordings that constitute the data for the present study, embodiment also comes in the form of the person filming the rider, possibly together with one or several other people acting as an audience. Hence the mountain-bike trail provides a public framework (C. Goodwin, 2018, p. 172) for the constitution of action. Being public, the actions are available to, and possibly co-constructed by, all participants, both rider and audience.

The hopscotch grid and the mountain-bike trail also resemble speech and gestures as semiotic resources in certain respects. Above all, Goodwin notes about the hopscotch grid that it "parses its structure into relevant units that are comparable to those being picked out with the language structures used to refer to it" (C. Goodwin, 2018, p. 173), exemplifying this with deictic expressions such as "this" referring to a specific square in the grid, where both the expression and the square are bounded units. In our analysis below, we will identify various patterns in how vocalisations and the mountain-bike trail parse their respective structure in comparable ways.

4. Data and Method

The data analysed here come from the Pinkbike channel on YouTube, self-described as "the world's largest mountain-bike community". Launched in 2015, this channel had 721,000 subscribers and over 245 million views in March 2024. The videos posted on Pinkbike include weekly "Friday Fails" compilations of user submissions of mountain-bike rides gone wrong, such as a rider crashing into a tree or crash-landing after being airborne. The data analysed here are taken from these Friday Fails video compilations. Friday Fails #1 was published in 2017 and Friday Fails #316 was published in mid-March 2024. A Friday Fails compilation is typically three to four minutes long and contains about 20-30 different video clips, or fails, meaning that an individual clip is typically a few seconds long.

Fail videos are filmed using either a head-mounted action camera or a hand-held device, typically a mobile phone. They are filmed from either a first-person perspective or a third-person perspective. In the dataset, the first-person perspective may involve a rider with a head-mounted camera having filmed a lengthy part of a ride, with the crash happening at some point during that ride. The third-person videos include one or more spectators, one or more of whom are filming. In some videos, spectators can be seen on-screen; in some, they can be heard off-screen. The spectators are typically stationed at some specific point along a mountain-bike trail, usually right next to some challenging part - or feature - of the trail. Such features include:

- the jump: a construction typically made of soil or wood that propels a rider upwards into the air at high speed;

- the gap jump: a jump construction as above followed by an opposite landing construction, with a void - a gap - in between;

- the drop: a construction typically made of wood or rock that causes a rider to continue straight out into the air - the impression being that the ground disappears beneath the bike;

- the skinny: a narrow and elevated part of the trail, such as a fallen log, which requires balance and control.

In order to successfully negotiate these features, the rider has to maintain appropriate speed, be positioned in a suitable way on the bike right before the feature, and then move in an appropriate way in relation to the bike and the feature while traversing the feature.

The selection of Friday Fails videos for the analysis presented here resulted from repeated viewing of a subset of these videos. The idea to analyse this type of material originated from an informal observation that there seemed to be vocalisations happening in these videos that could merit systematic investigation. In contrast with various online fail videos that contain voiceover sounds, the vocalisations in the Friday Fails videos are produced by participants in situ.

In a first iteration, nine Friday Fails compilations (#199-203 and #239-242) were viewed in their entirety. Those nine compilations were chosen for no other reason than to get the systematic investigation started somewhere. Notes were made about all fail sequences that contained some form of vocalisation produced by a rider or spectator (some fails are entirely silent, at least as far as what is captured in the video, and some of them are partly silent because swear words have been edited out). Anything from a cry by a rider to laughter or a wohoo by the person filming qualified as a vocalisation at this stage. This yielded a total of 229 fails each containing one or more vocalisations. Notes were made of anything worthy of further analysis.

In the second iteration, the fails were assigned to tentative chronological phases of a mountain-bike crash (e.g., "something goes wrong") and to different categories (such as bodily movement, speech, laughter or (other) vocalisation), and they were categorised depending on which participant produced the movement or the sound. In a third iteration, the phases were finessed into the five phases presented in the analysis below. At this point, the analysis was also restricted to include only videos filmed from a third-person perspective. Such videos had been found to typically contain more, and more varied, vocalisations, and this also represented a way to impose a certain coherence on the dataset selected. In a fourth iteration, eight other Friday Fails compilations (#1, 11, 21, 31, 41, 51, 61, 71) were viewed to verify the previous observations and to identify any additional aspects of interest. In the fifth and final iteration, the analysis focused on vocalisations pertaining to movement in relation to the ground. Hence the extracts analysed have been qualitatively selected with reference to the aim of the article, which is to gain an understanding of vocalisations in relation to movement and the ground in mountain-bike crashes. For this reason, the analysis presented below is not representative of all the Friday Fails data, nor of all mountain-bike crashes.

The data were analysed using multimodal interaction analysis (Broth & Keevallik, 2020; Mondada, 2018b). The transcriptions presented focus on three aspects: (i) the vocalisation, (ii) the trail and (iii) the movements of the rider, including the bike.

The first author of this article has been a sporadic mountain-bike rider for four years. The technical aspects of mountain biking presented in this article have been fact-checked by an experienced rider.

5. Analysis

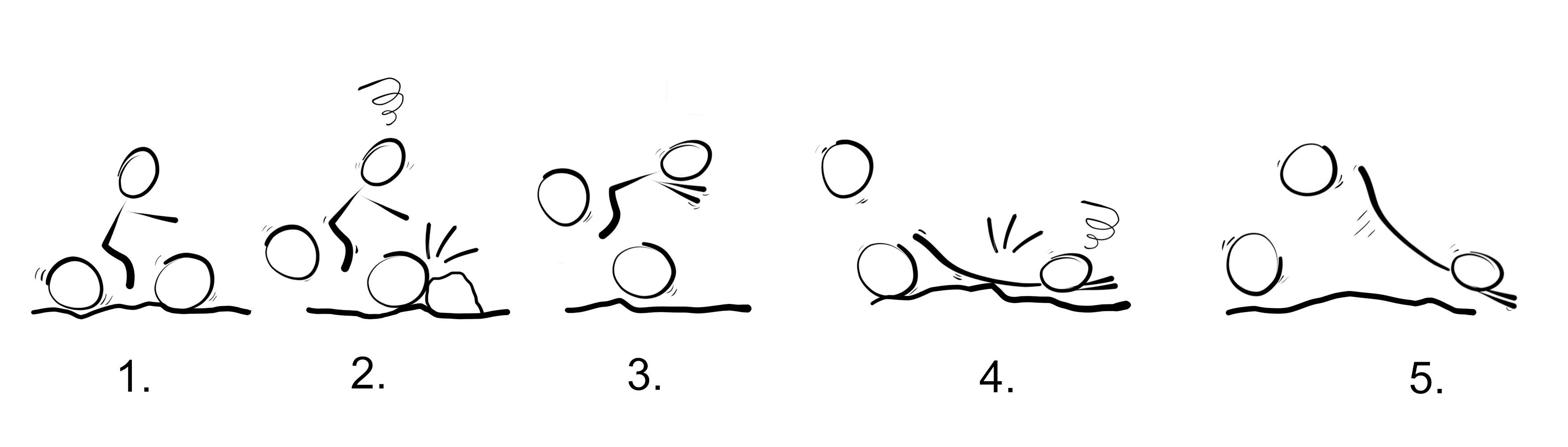

Based on the movement of the rider in relation to the mountain-bike trail and on the co-ordinated vocalisations, the phases of a mountain-bike crash as reflected in our data can be illustrated as in Figure 1. Phase 1 involves the rider cycling along. Phase 2 is when something goes wrong, endangering the continued ride. Next, Phase 3 is continued movement, either in the air as in Figure 1 or in contact with the ground. Phase 4 is the impact part of the crash, that is, the "crash proper", when the movement of the rider and/or the bike is stopped by a material structure in the surround; this often involves the rider coming into contact with the ground. The final Phase 5 is the movement of the rider and the bike post-impact, before they come to a complete stop or the rider initiates a new (controlled) movement.

Figure 1. The five phases of a mountain-bike crash.

Each of these phases can be vocalised, either by the rider or by the audience, but need not be (and most often is not). Not all phases are necessarily present or discernible in all crashes. For instance, Phases 2 and 4 may occur just about simultaneously, so that there is no Phase 3, and there need not be a precise moment when Phase 2 turns into Phase 3. The duration of vocalisations can be bounded to a single phase or to more than one phase. It should be noted that the phases of the mountain-bike crash are described from the analyst's perspective, as an idealised or maximally possible rendering of the crash. By contrast, whether participants' vocalisations occur within or across phase boundaries is an indication of what they themselves orient to.

Two kinds of participants appear in the extracts: riders (RID) and spectators (SPE). A spectator may be the person filming or someone else who is watching. In most cases it is possible to make a reasonable guess as to whether it is the person with the camera or someone else in the audience who is vocalising, but not always. Since this distinction is not relevant for the analysis performed here, a common SPE category is used. The extracts are assigned the number of the Pinkbike Friday Fails video compilation in which they appear. The time stamp given represents the start of the extract in minutes and seconds from the beginning of the compilation. The analysis below proceeds phase by phase, with extracts selected to show how vocalisations have the function of imitating the mountain-bike trail - that is, a geomorphopoetic function.

5.1 Phase 1: Cycling along

During Phase 1 of a mountain-bike crash the rider is making their way along the trail, with seemingly nothing untoward happening. In Extract 1, Figure 0 shows the whole-screen view at the beginning of the video clip. At the bottom of the image, we see part of a helmet, indicating that the filming is done by a head-mounted camera worn by a spectator. The camera is pointing towards a location where a rider will emerge into the open from a woody part of a trail. Soon after leaving the wood, the trail passes a bump, which is a gravel jump (top middle in the image). Further on, towards the bottom right in the picture, there is a fairly high wooden jump construction. This is the feature to be attempted by the rider. Figure 1 is a close-up (of the rider having emerged from the woods and passed the gravel jump). In other words, this is a screen-dump of only part of the video screen. All of the remaining images in the analysis below are close-ups of the same type that visually focus on what is relevant for the analysis.

Figure 1 in Extract 1 shows the rider at the beginning of a vocalisation, namely an UEH: produced by the spectator as the rider lands after the gravel jump (line 01). Immediately following this, the spectator vocalises ten consecutive PAP, co-ordinated with the rider pedalling to build speed in the approach to the wooden jump (line 02). Figure 2 shows the rider in the middle of pedalling, about one-third of the way to the jump, and Figure 3 shows the rider at the end of the last PAP, having just reached the ramp.

Extract 1. Friday Fails #21, 01:24

Open in a separate windowIn line 02, the rider is moving along an even and fairly level gravel trail. The vocalisation is produced by the spectator, who is not vocalising their own action but rather sounding for the other (Keevallik et al., 2023), in this case inhabiting the rider's effort as a way of encouraging their ride towards the challenging jump. There are a number of factors supporting this interpretation. First, both the beginning and the end of the sequence of PAP sounds in line 02 co-occur precisely with the part of the trail where the rider is pedalling towards the jump. Second, the tempo of the vocalisation is fast, mimicking the high speed that the rider needs to build in order to manage the jump. Third, it is the same sound - PAP - that is being repeated, and that sound can be seen as inhabiting the pedalling movement that needs to be performed again and again by the rider. The loudness of the vocalisation may have a dual function here: it embodies the intensity of the rider's movement along this part of the trail, and it is shaped to be perceived by the rider.

This tempo, the prosody, and the voice quality of the vocalisation together form a rhythm that inhabits the rider's effort and movement across the ground. The repetitive vocalisation, which is presumably hearable by the rider, is reminiscent of other repetitions used as incitement in settings involving strong effort (Grahn et al., 2023; Reynolds, 2017). PAP does not carry a conventionalised meaning but obtains its meaning from the local context. Significantly, the vocalisation ends at the point where the material properties of the ground change (line 02, Figure 3). This is where the rider needs to shift their attention from just building speed to positioning themselves for the jump, which requires a change in both physical and cognitive effort. The spectator's ensuing silence (not shown in Extract 1) may be in recognition of this.

In sum, this analysis of Extract 1 has shown how Phase 1 - cycling along - is geomorphopoetically vocalised by the spectator as a way of encouraging the rider.

5.2 Phase 2: Something goes wrong

During Phase 2, something occurs that is oriented to by the participants as "something goes wrong".

In Extract 2, a rider is balancing along a skinny a couple of decimetres above the ground when the front wheel veers off. Figure 1 shows the moment when the front wheel hits the ground below the skinny. This co-occurs with the rider emitting a short muffled OH.

Extract 2. Friday Fails #240, 01:28

Open in a separate windowThe vocalisation in Extract 2 is brief and corresponds to a small part of the front wheel of the bike coming into contact with a correspondingly small portion of the ground below the skinny (line 01, Figure 1). Hence the brief duration of the vocalisation matches the restricted size of the point of contact between the bike and the ground, signalling that something is happening highly momentarily. In the terms used by Goodwin (2018), the temporally bounded vocalisation is comparable to the spatially bounded portion of the trail. Figure 1 shows that the rider's left leg has come off the pedal and that the saddle is in a raised position. Having the saddle lowered when riding along a skinny will lower the rider's centre of gravity and enable better balance; with the saddle raised, the rider is pushed down into it. The brevity, loudness and muffled quality of the OH, together with the movement of the body in relation to the bike and the ground, indicate that this is an expression of pain. However, as it occurs in a social setting, this geomorphopoetic vocalisation may go beyond that and also be intended to provide the spectator with a reading (Goffman, 1978) of what is happening and how it is to be understood, that is, as a quick and painful deviation from the ride along the skinny.

In Extract 3, it is instead a spectator who vocalises the something-goes-wrong phase. As in Extract 2, this is a very short vocalisation, but this time it is an ingressive .HH (Extract 3, line 01) - that is, a gasp (Ben-Moshe, 2023). Here, a rider is attempting a gap jump. At the point in time when the spectator's gasp is emitted, it is clear that the rider is too low in the air to successfully make it onto the landing ramp. Hence in this case the relevant materiality of the mountain-bike trail providing semiotic structure (C. Goodwin, 2018) is the air space between the two ramps of the gap jump. Relatedly, Lloyd (2019) shows how a rider's too slow pace and too low centre of gravity lead to a crash in a gap jump.

Extract 3. Friday Fails #200, 01:23

Open in a separate windowThe brevity of the vocalisation matches the short time that the rider is airborne and too low in the air. As in Extract 1, this is an example of the spectator taking another's perspective (Keevallik et al., 2023). However, instead of voicing encouragement, the vocalisation in Extract 3 seems to be an emotional expression of fright. Further, as in Extract 2, there is an element of pain, but rather than immediate pain it is here anticipated pain: the current position is not painful for the rider, but their landing may be very painful. The spectator's gasp can be seen as a point of departure for ensuing embodied actions by participants (Goffman, 1978; M. H. Goodwin et al., 2012; Keevallik & Ogden, 2020). For instance, the spectator may be readying themselves to rush towards the rider in the next phase.

Extract 4 is another example of Phase 2: something going wrong. It again involves a gap jump, again with a rider in the air, but this time it is the rider who vocalises. Figures 1 and 2 show the situations when the rider starts and stops vocalising, respectively.

Extract 4. Friday Fails #71, 00:02

Open in a separate windowThe vocalisation in Extract 4 is a loud and long O::AH:::: that geomorphopoetically vocalises the rider's flight through the air. As in Extract 3, the rider is positioned too low in the air to be able to make it onto the landing part. It is worth noting that both the length of the air space and the duration of the vocalisation are greater in Extract 4 than in Extract 3, reflecting how vocalisations inhabit movement along the trail.

As in Extract 3, the vocalisation in Extract 4 may carry an anticipation of pain. It may also, given its longer duration, embody the rider's feeling of a lack of control over the ride. The expression of a lack of control and the anticipation of pain may also go together with the loudness of the vocalisation.

An alternative analysis of Extract 4 is that the vocalisation inhabits both the something-goes-wrong phase and the next phase - continued movement. At any rate, the vocalisations in Extracts 3 and 4 both end before the rider hits the ground. This can be assumed to be part of the meaning-making in both extracts: other actions are needed next.

5.3 Phase 3: Continued movement

After something has gone wrong, the movement of the rider and the bike continues. This is Phase 3 of the mountain-bike crash. In some cases, this phase is so brief that there is no room for vocalisation. For example, this is so in Extract 3, where the rider hits the landing ramp immediately after the spectator's gasp.

Right before Extract 5, a rider has started going downhill from a stationary position but has failed to achieve a proper position on the bike (this is Phase 2, something going wrong). The downhill trail contains roots and bumps, and the rider proceeds slowly downwards. Their right foot is not on the pedal, as can be seen in Figure 1, meaning that they do not have full control over the bike. The ride is accompanied by a vocalisation produced by a spectator - whose helmet can be seen at the bottom of Figures 1 and 2 - taking the form of three yo: sounds uttered with a laughing voice.

Extract 5. Friday Fails #41, 01:02

Open in a separate windowThe rider in Extract 5 bounces up and down three bumps in the trail (lines 01-03). Figure 1 shows the rider at the end of the first bounce and Figure 2 shows them at the end of the third bounce. The spectator vocalises in overlap with the third bounce: <*yo: yo: yo:*>. The laughter, slowness and moderate intensity of the vocalisation shape the rider's movement along the trail as amusing and relaxed (compare with the loudness of the vocalisations in Extracts 2-4).

As in Extract 1, there is repetition involved, but the encouraging function of repetitions seen in certain physically strenuous situations (Grahn et al., 2023; Reynolds, 2017) seems to be absent. Instead, the repeated vocalisations in Extract 5 seem to represent more of an empathetic acknowledgement (Keevallik et al., 2023): the spectator inhabits the rider's movements up and down the bumpy trail. The yo: sounds geomorphopoetically inhabit the type of movement involved, that is, the bounces along the trail.

It is also worth noting that the vocalisation in Extract 5 differs from those in the extracts discussed above in terms of the timing of its beginning and end. In Extracts 1-4 above, the vocalisations were all precisely timed with the movement and the part of the trail that they inhabited. By contrast, the spectator's vocalisation in Extract 5 begins only after the first two bounces and is timed with the third bounce. It is quite possible that a repeated pattern such as this can only be inferred and inhabited vocally after repeated bounces have occurred.

Extract 6 is another example of Phase 3: the continued movement after something has gone wrong. Here the rider has lost their balance going downhill in Phase 2. This is followed by movement at great speed along a wide and even trail. This continued movement is a wobbly ride with the rider veering left and right (to successfully manage this part of the trail at this speed, the rider would need to go straight).

Extract 6. Friday Fails #200, 03:16

Open in a separate windowAfter the rider has veered left and right (line 01) a spectator vocalises >oh LO LO LO LO(::)< as the rider veers left again and starts falling (line 02). This vocalisation is fast and loud, embodying urgency and severity. As with yo in Extract 5, the repetition of LO in Extract 6 geomorphopoetically inhabits the movement of the rider in relation to the trail; in this context, the repeated LO sounds indicate an undulating movement. Further, also as in Extract 5, the vocalisation is timed with the latter part of the movement, which may again indicate that the spectator first had to infer a pattern from visual cues before vocalising it.

Right before Extract 7, a rider has failed a landing after a jump. Phase 3 for this rider involves continued forward movement along a level trail, with the rider's body moving forward across the bike. This is vocalised by a spectator as OH::::: (lines 01-02), starting immediately after the failed landing (Figure 1) and ending right before - or possibly even at - the point of impact (Figure 2). In other words, the whole of Phase 3 is vocalised.

Extract 7. Friday Fails #199, 00:43

Open in a separate windowThe vocalisation is a continuous and loud sound with a level pitch, geomorphopoetically inhabiting the rider's forward motion in relation to the bike and the trail.

5.4 Phase 4: Impact

The impact phase is the "crash proper" part of the crash where the ride is stopped by a material structure in the surround.

In Extract 8, a rider runs straight into a tree (Figure 1). A spectator simultaneously vocalises UH. This is a brief and loud vocalisation, inhabiting a severity of the situation and feeling the other's pain (Keevallik et al., 2023).

Extract 8. Friday Fails #200, 00:30

Open in a separate windowThe brevity of the vocalisation in Extract 8 geomorphopoetically matches the short period of time in which the rider hits the tree as well as the small amount of space that the impact phase occupies along the trail - if space is seen as the trajectory of a rider along a horizontal axis.

In Extract 9, it is also a spectator who vocalises the impact phase. Here, however, the vocalisation is a lengthened OH:::::. Right before this extract, a rider has attempted a jump but is infelicitously positioned (Phase 2) and begins a forward rotation, toppling over the bike in the air (Phase 3). The vocalisation is produced by one of the spectators and begins towards the end of Phase 3 as the front wheel is about to touch the ground (Figure 1, line 01). It continues during Phase 4: impact (Figure 2, line 02) and even into Phase 5: post-impact movement (Figure 3, line 03). Throughout Phases 1-5 of this crash there are several vocalisations from different spectators, but the analysis here focuses on this one vocalisation that begins right before the impact phase.

Extract 9. Friday Fails #199, 03:08

Open in a separate windowThe voice quality of this vocalisation indicates that it is more controlled and relaxed than the one in Extract 8, inhabiting a less severe understanding of the situation. This is also evidenced by the tapering-off of the OH::::: towards the end. Geomorphopoetically, this vocalisation inhabits the rider's continuous downward movement during the landing part of the jump (see Figures 1-3). It should also be noted that the impact is already predictable when the rider is in the air after the jump (Phase 3), which may have contributed to the duration of the vocalisation (by causing it to begin sooner). By contrast, the impact in Extract 8 occurs very suddenly and unpredictably, with Phases 2 and 3 (something going wrong and continued movement, respectively) occurring only tenths of a second before the rider hits the tree.

5.5 Phase 5: Post-impact movement

After the rider's trajectory has momentarily stopped at the point of impact, the rider's and the bike's momentum make them continue moving post-impact. This is the final phase of the crash, Phase 5. The rider and the bike may either maintain physical contact with each other or go off in different directions.

Extract 10 overlaps with the end of Extract 9 and shows Phase 5 of the same crash, during which the rider continues gliding down the slope. Here, three spectators are vocalising in overlap. Figure 1 shows the rider at the end of Spectator 2's vocalisation (a shoulder and an arm can be seen sticking up from behind the slope). At this point, the rider is near the bottom of the slope and the bike has flown off behind the tree to the left in the image.

Extract 10. Friday Fails #199, 03:08

Open in a separate windowSpectator 1 is the person who produced the vocalisation in Extract 9, and the last part of their lengthened vocalisation extends into Extract 10. Spectator 3 says something that is difficult to decipher. Spectator 2 begins vocalising at the beginning of Phase 5, using repeated OH sounds (OH OH:::↓). The voice quality of Spectator 2's vocalisation seems to convey disappointment, inhabiting the rider's failure to successfully complete the jump. Indeed, the vocalisation here resembles a conventionalised oh oh that marks surprise or disappointment about some untoward event. What is more, Spectator 2's vocalisation has a relaxed and controlled quality to it, portraying the situation as non-urgent. The lengthening of the second OH:::↓ geomorphopoetically inhabits the rider's continued movement, and the lowered pitch is congruent both with a conventionalised oh oh expression and with the rider's downward movement along the slope.

In Extract 11, it is the rider who vocalises the phase of post-impact movement along the trail. They have attempted a jump at high speed but were positioned too far forward on the bike, resulting in a crash landing (Phases 1-4). In Phase 5, the rider and the bike are propelled into a rolling forward movement along the trail (line 01, Figure 1). As this rolling movement continues, the rider vocalises a series of AH:: sounds (line 02, Figure 2). These sounds end as the rider and the bike come to a final stop behind a tree (line 02, Figure 3).

Extract 11. Friday Fails #21, 00:49

Open in a separate windowThe vocalisation has a tremulous and staccato-like quality, embodying the rider's strain and, presumably, pain. The repetition and the rising and falling pitch of the second and third units geomorphopoetically inhabit the forward-up and forward-down movements of the rider's and the bike's cycloid trajectory along the ground.

6. Conclusion

This article has identified some of the ways in which mountain-bike riders and spectators employ movement in relation to the mountain-bike trail as a semiotic structure in interaction by means of vocalisations. It is clear that vocalisations in conjunction with mountain-bike crashes fulfil a number of different functions, such as encouragement or the expression of pain, fright, amusement or disappointment. The characteristics of these vocalisations are dependent on what the relevant bodies are doing, such as flying through the air or rolling along the ground post-impact. Those characteristics are also finely tuned to the duration, repetitiveness and various other qualities of the relevant events. In conclusion, we will take a closer look at the vocalisations in relation to the associated movement across the ground, clustering these geomorphopoetic vocalisations by similarities and differences rather than by crash phase.

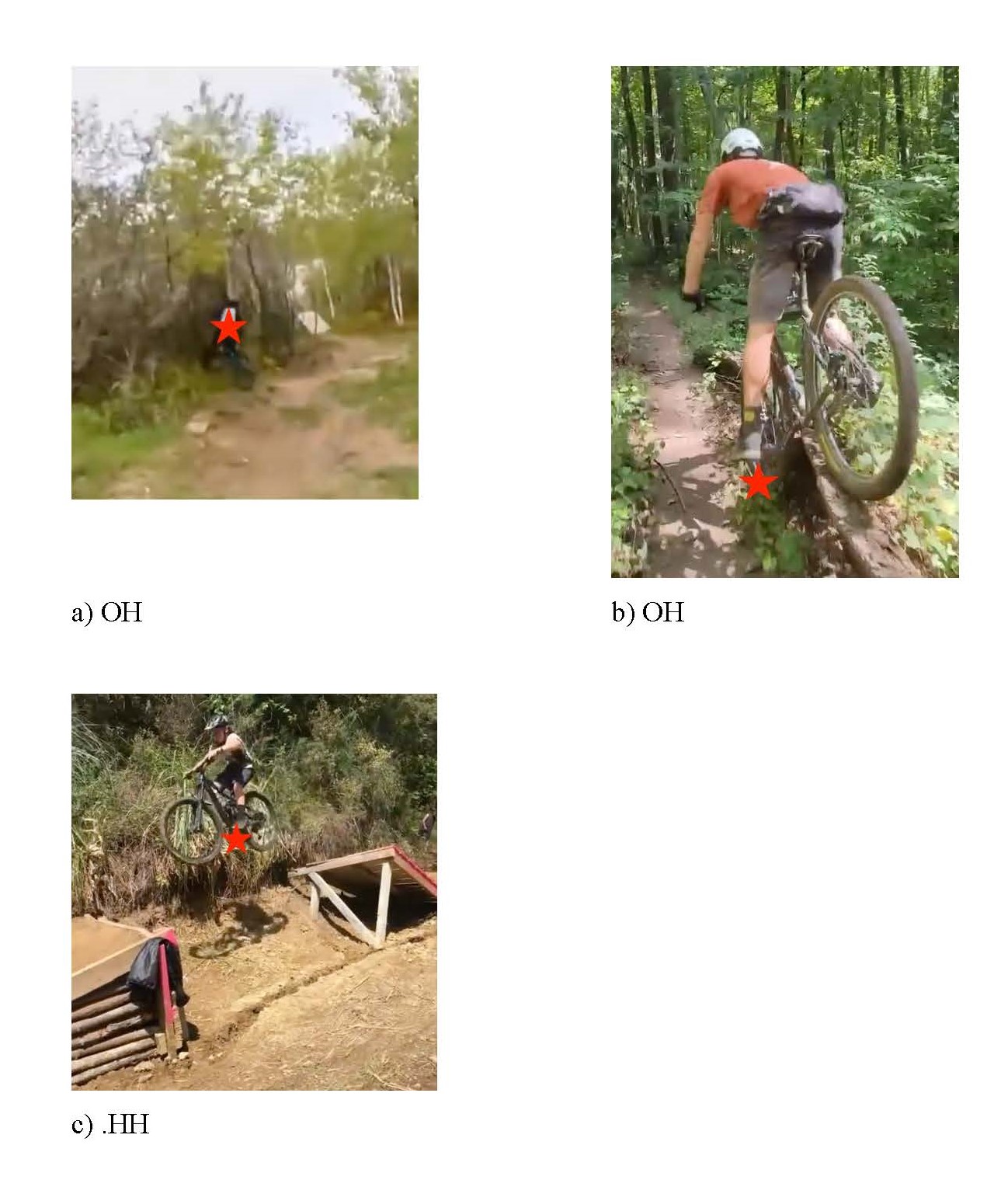

One group of geomorphopoetic vocalisations are characterised by lengthened vocalisations of vowels: OH::: and AH:::. These vocalisations inhabit extended and continuous movement along a fairly even part of the trail, either in the air (Figure 2a and the bike (top arrow) in Figure 2d) or on the ground (Figure 2b and 2c, and the rider (bottom arrow) in Figure 2d).

Figure 2. Geomorphopoetic vocalisations inhabiting extended and continuous movement along a fairly even part of the trail.

A second group of geomorphopoetic vocalisations are very brief and take the form either of an UH, OH or of an ingressive .HH. These vocalisations sometimes inhabit a brief contact between, on the one hand, the rider and/or the bike and, on the other, an unyielding surface along the trail such as a tree (Figure 3a) or the ground below a skinny (Figure 3b). Alternatively, they inhabit a very brief portion of a ride, such as a situation where a cyclist is too low in the air during a quick jump (Figure 3c).

Figure 3. Geomorphopoetic vocalisations inhabiting a brief contact with an unyielding surface or a brief portion of a ride.

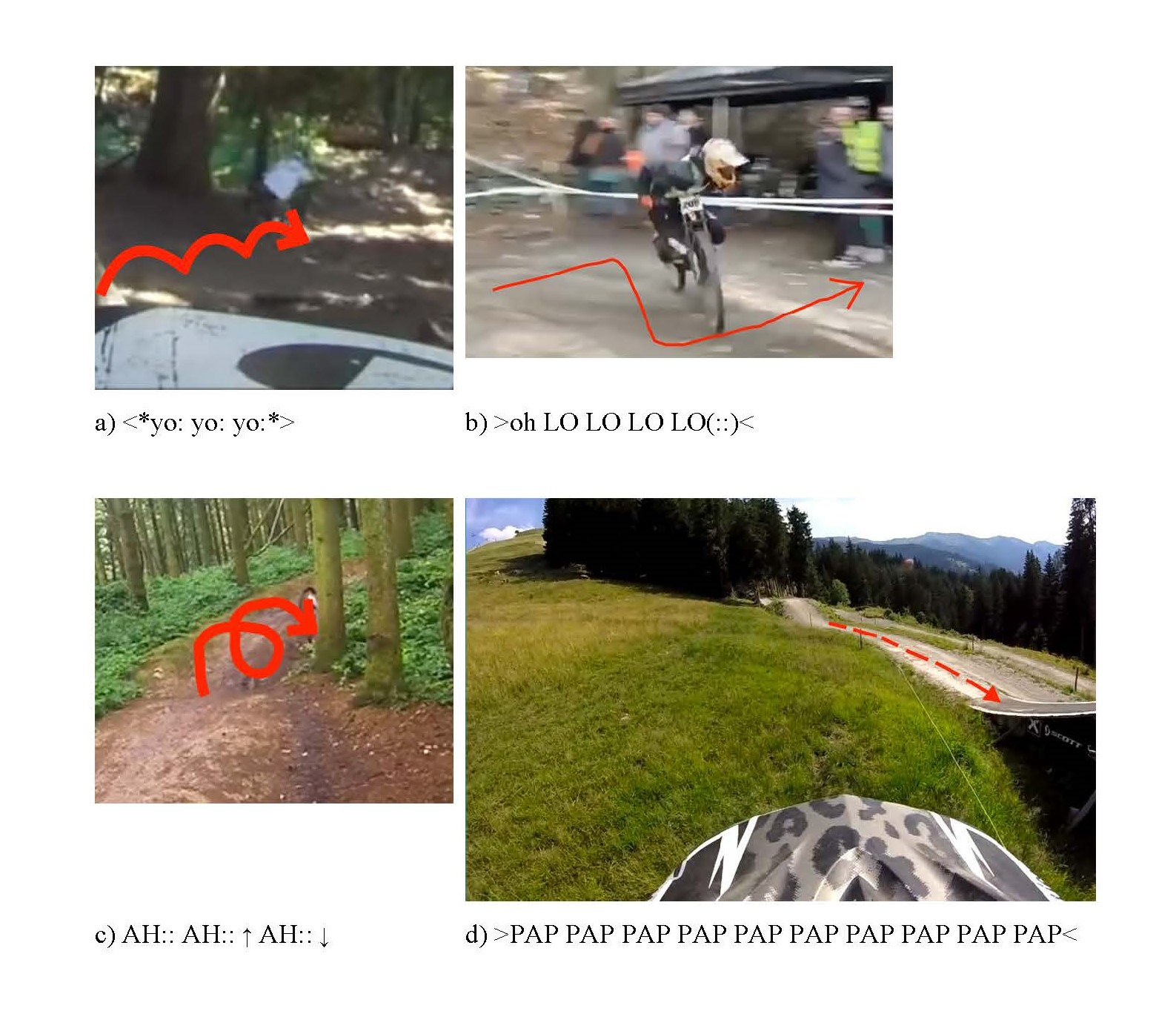

The third and final group of geomorphopoetic vocalisations inhabit the repetition of a specific movement and a property of the ground, such as bumps going downhill (Figure 4a), veering left and right along a level slope at high speed (Figure 4b), tumbling along the trail (Figure 4c) or repeated pedalling along a level surface (Figure 4d).

Figure 4. Geomorphopoetic vocalisations inhabiting the repetition of a specific movement and a property of the ground.

Across these three groups of geomorphopoetic vocalisations, it is clear that the mountain-bike trail parses its own structure into units (C. Goodwin, 2018) that are relevantly picked out by the vocalisers. Specifically, the vocalisations in Figure 2 pick out the extended duration of the movement and the evenness of (that portion of) the trail, whereas those in Figure 3 pick out the brevity of the movement and the small space involved. The vocalisations in Figure 4 pick out the repeated movements supported by the properties of the trail. All of these cases support the claim that the mountain-bike trail provides a public framework (C. Goodwin, 2018) for identifying and interpreting mountain biking, within which both riders and spectators convey their understanding of the ongoing biking event. In this context, mountain-bike riders and spectators exploit the highly versatile nature of vocalisations (Keevallik & Ogden, 2020) for rapid, varied and finely tuned interaction, with geomorphopoetics at its core.

References

Albert, S., & vom Lehn, D. (2023). Non-lexical vocalizations help novices learn joint embodied actions. Language & Communication, 88, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2022.10.001

Ben-Moshe, Y. M. (2023). Hebrew stance-taking gasps: From bodily response to social communicative resource. Language & Communication, 90, 14-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2022.12.006

Broth, M., & Keevallik, L. (2020). Multimodal interaktionsanalys (Upplaga 1). Studentlitteratur.

Cherrington, J. (Ed.). (2024). Mountain Biking, Culture and Society. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003361626

Deemter, K. van, & Peters, S. (1996). Semantic ambiguity and underspecification. CSLI Publ.

Dingemanse, M. (2020). Between Sound and Speech: Liminal Signs in Interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 188-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1712967

Ericsson, S. (2005). Information Enriched Constituents in Dialogue [Thesis]. http://hdl.handle.net/2077/16609

Goffman, E. (1978). Response Cries. Language, 54(4), 787-815. https://doi.org/10.2307/413235

Goodwin, C. (1979). The Interactive Construction of a Sentence in Natural Conversation. In G. Psathas (Ed.), Everyday Language: Studies in Ethnomethodology(pp. 97-121). Irvington Publishers.

Goodwin, C. (2018). Co-operative action. Cambridge University Press.

Goodwin, M. H., Cekaite, A., & Goodwin, C. (2012). Emotion as Stance. In A. Perakyla & M.-L. Sorjonen (Eds.), Emotion in Interaction (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199730735.003.0002

Grahn, I.-L., Lindholm, C., & Huhtamäki, M. (2023). Accounting for changes in series of vocalisations - Professional vision in a gym-training session. Journal of Pragmatics, 212, 72-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2023.05.006

Hoey, E. M. (2020). Waiting to Inhale: On Sniffing in Conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 118-139. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1712962

Hofstetter, E. (2020). Nonlexical "Moans": Response Cries in Board Game Interactions. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 42-65. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1712964

Hofstetter, E., & Keevallik, L. (2023). Prosody is used for real-time exercising of other bodies. Language & Communication, 88, 52-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2022.11.002

Hofstetter, E., Keevallik, L., & Löfgren, A. (2021). Suspending Syntax: Bodily Strain and Progressivity in Talk. Frontiers in Communication, 6 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2021.663307

Huhtamäki, M., & Grahn, I.-L. (2022). Explicit positive assessments in personal training: Their design and sequential and embodied environment. Journal of Pragmatics, 188, 108-128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2021.12.001

Keevallik, L. (2014). Turn organization and bodily-vocal demonstrations. Journal of Pragmatics, 65, 103-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.01.008

Keevallik, L., Hofstetter, E., Löfgren, A., & Wiggins, S. (2024). Repetition for real-time coordination of action: Lexical and non-lexical vocalizations in collaborative time management. Discourse Processes, 0(0), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2023.2165027

Keevallik, L., Hofstetter, E., Weatherall, A., & Wiggins, S. (2023). Sounding others' sensations in interaction. Discourse Processes, 0(0), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2023.2165027

Keevallik, L., & Ogden, R. (2020). Sounds on the Margins of Language at the Heart of Interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1712961

Lloyd, M. (2019). "You just took the jump too slowly": A single case analysis of a mountain bike crash. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v2i2.113197

Mondada, L. (2018a). Greetings as a device to find out and establish the language of service encounters in multilingual settings. Journal of Pragmatics, 126, 10-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2017.09.003

Mondada, L. (2018b). Multiple Temporalities of Language and Body in Interaction: Challenges for Transcribing Multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85-106. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878

Mondada, L. (2020). Audible Sniffs: Smelling-in-Interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 140-163. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1716592

Pehkonen, S. (2020). Response Cries Inviting an Alignment: Finnish huh huh. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 19-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1712965

Reber, E., & Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2020). On "Whistle" Sound Objects in English Everyday Conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 164-187. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1712966

Reynolds, E. (2017). Description of membership and enacting membership: Seeing-a-lift, being a team. Journal of Pragmatics, 118, 99-119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2017.05.008

Rohman Roth, A.-C. (2022). ‘Här ska kraften vara på!' Interaktion vid körövningar: En studie av instruktioner om luft och andning. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-117610

Schlangen, D. (2003). A Coherence-Based Approach to the Interpretation of Non-Sentential Utterances in Dialogue [Thesis]. https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/1992167

Sorjonen, M.-L., & Peräkylä, A. (2012). Introduction. In A. Perakyla & M.-L. Sorjonen (Eds.), Emotion in Interaction (pp. 3-15). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199730735.003.0001

Weatherall, A., Keevallik, L., La, J., Dowell, T., & Stubbe, M. (2021). The multimodality and temporality of pain displays. Language & Communication, 80 56-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2021.05.008

Weatherall, A., & Robles, J. S. (2021). How emotions are made to do things: An introduction. In J. S. Robles & A. Weatherall (Eds.), How Emotions Are Made in Talk (pp. 1-24). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

1 The authors wish to thank Jonas Lindberg at the University of Gothenburg for coming up with this term to match our concept, and for letting us use it.↩