Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Displaying a Critical Stance:

Eyebrow Contractions in Children's Multimodal Oppositional Actions

Vivien Heller, Nora Schönfelder & Denise Robbins

University of Wuppertal

Abstract

This study examines eyebrow contractions within processes of argumentative decision-making in children's interaction. Based on a collection of 23 instances, we examine this subtle resource in two oppositional actions: contradicting and putting something into question. We describe how eyebrow contractions are combined with other facial (e.g. nose wrinkling, squinting/opening the eyes, gaze aversion/confrontational gaze), bodily and verbal and pro-sodic resources to display a critical stance. The analysis demonstrates that the two opposi-tional actions are accomplished through distinct clusters of resources, which either mitigate or increase their confrontational import. Multimodal displays of critical stance thus vary from mild-ly critical to reproachful-critical and ironic-critical and contribute in different ways to the interac-tive trajectory of decision-making.

Keywords: facial expression, eyebrow movement, opposition, critical stance, affective stance

1. Introduction

Disputes constitute a frequent discursive practice in children's families, peer groups and classrooms (e.g. Goodwin, 1990; Danby & Theobald, 2014; Heller et al., 2020). They are characterised by oppositional actions (Marrese et al., 2021) with which participants interactively manifest alternative or incompatible positions. In such actions, affective and epistemic stances serve as crucial meaning components with which speakers display their alignment in relation to their utterance, thereby positioning themselves and (dis)aligning with their co-participants' positions (Ochs, 1996; Heritage & Raymond, 2005; Du Bois, 2007; Du Bois & Kärkkäinen, 2012; Goodwin et al., 2012). The present study focuses on the display of critical stances (Tainio, 2012) in children's argumentative decision-making. Building on recent interactional research on multimodal stance-taking, we examine how a specific communicative resource, the contraction or pulling together of eyebrows, also known as 'frowning' (Darwin, 1872; Ruusuvuori & Peräkylä, 2009; Kaukomaa et al., 2014) or eyebrow furrowing (Li, 2021), is combined with other facial (e.g. nose wrinkling, squint-ing/opening the eyes, gaze), bodily (e.g. posture) as well as verbal and prosodic resources to form publicly visible 'multimodal gestalts' (Mondada, 2014) of critical stance (Tainio, 2012; Waring, 2012). Taking into account their particular turn position and sequential placement, we describe how children use such multimodal critical stance displays to calibrate oppositional actions as more or less confrontational. In our video recordings of children's decision-making, eyebrow contractions are predominantly used for the oppositional actions contradicting and putting something into question. In these actions, eye-brow contractions are distinctive with respect to their prototypical co-occurring facial displays: when contradicting, the eyebrows are consistently contracted and lowered. Common but not obligatory co-occurring resources are narrowing the eyes, averting the gaze from the recipient and wrinkling the nose. In this configuration of facial resources, eyebrow contractions embody a rather 'mild' critical stance. During questioning, on the other hand, the eyebrow contraction is prolonged and accompanied by either an upward or downward movement that can be combined with a gaze directed towards the recipients. Depending on whether the eyes are opened or narrowed and which prosodic resources are used, the contraction of the eyebrows contributes to making the questioning action more or less confrontational. The distinct multimodal gestalts thus allow children to convey and calibrate critical stances, this way making either an elaboration, justification or acceptance of a proposal relevant.

Our analysis of multimodal displays of critical stance is intended to contribute to the emerging research on how facial expressions bring about subtle aspects of interactional conduct (see Goodwin & Goodwin, 1986; Ruusuvuori & Peräkylä, 2009; Goodwin & Alim, 2010; Bavelas et al., 2014; Kaukomaa et al., 2014; Clift, 2021; Heller, 2021; Li, 2021; Feyarts et al., 2022 and Andries et al., 2023 for overviews). Beyond that, the findings also extend research on (children's) multimodal affective and epistemic stance-taking (Haddington, 2006; Streeck, 2009; Cekaite, 2012; Du Bois & Kärkkäinen, 2012; Goodwin et al., 2012; Tainio 2012; Cook, 2014; Iwasaki, 2015; Heller, 2018, 2021; Hübscher et al., 2019).

2. Theoretical Frame

2.1 Contracting eyebrows as a conversational resource

More than other bodily resources, facial expressions are viewed as a direct expression of emotional and cognitive states or processes. This is especially true for the upper parts of the face, the eyebrows and eyelids. For example, the French artist Lebrun (1734/1980) described the contraction of the eyebrows and lowering of their inner corners (combined with a widening of the nose and pulling down the corners of the mouth) as an expression of contempt. According to Darwin (1872), frowning – a facial display that accrues when individuals 'lower the eyebrows and bring them together, producing vertical furrows on the forehead' – is associated with 'the perception of something difficult or disagreeable, either in thought or action' (p. 221).

In the field of psychology, Ekman was the first to describe eyebrow movements systematically. He distinguishes three basic movements (that can also be combined): (i) raising the inner corners of the eyebrows; (ii) raising the outer corners; and (iii) pulling down and drawing together the eyebrows, causing a wrinkling or the deepening of a wrinkle between the brows (Ekman, 1979: 173ff; Ekman, 2007). Similar to Darwin, Ekman associates the latter movement with the expression of 'anger, disgust, perplexity and more generally with difficulty of any kind' (Ekman, 1979: 182). However, Ekman points out that eye-brow movements fulfil two different functions. In addition to expressing emotions, they can also serve as conversational signals to emphasise or punctuate talk (also Chovil, 1991).

In contrast to psychological research, interactional research conceptualises facial displays not as a reflection of inner emotional or cognitive states, but as communicative displays. Thus, they can be understood as culturally evolved and socially shared resources for conveying affective and epistemic stances (Dix & Groß, 2023/this issue). Like pragmatic gestures (Streeck, 2009) or 'operators' (Kendon, 2004) they are used to contextualise what an action is designed to do in a particular interactional moment and signal the speaker's (or recipient's) stance toward this upcoming or ongoing action. In this regard, Kaukomaa et al. (2014) examine frowns as pre-beginning elements of conversational actions. Their analysis of 12 instances of turn-opening frowns shows that they are used in this particular turn position to project that the upcoming action involves difficulties associated with negative evaluation, disaffiliation or epistemic challenge (also Ruusuvuori & Peräkylä, 2009: 381–382; Kääntä 2014: 102). Such turn-opening frowns are typically accompanied by the speaker's gaze aversion and foreshadow a problem that will be addressed in the upcoming turn of talk, this way preparing the recipient to cope with that problem. Thus, they are part of the multimodal stance that is conveyed in the upcoming turn, for example, a negative evaluation or a disaffiliative utterance. It is interesting to note that not all disaffiliative turns are projected by frowns. The authors observe that disaffiliations expressed without frowning are often more straightforward; in contrast, turn-opening frowns convey that the speaker is still 'contemplating' (Kaukomaa et al. 2014: 145) the matter at hand. They also note that co-participants do not seem to show much awareness of the frowns as such; rather, their next action is produced as a response to the whole action that involved the frown.

In her study of negative assessments, Li (2021) describes eyebrow contractions in another sequential context. She finds that incomplete syntax, eyebrow furrows and head shakes form a set of multimodal resources for performing a negative assessment of a non-present party. By producing eyebrow furrows and pouting the lower lip immediately after abandoning the verbal utterance at the point when the negative assessment term is due, they convey their orienta-tion to the assessment as a delicate matter and interactional problem.

Eyebrow contractions also serve as a conversational resource for initiating a repair, either combined with interjections such as [hɛ] (Oloff, 2020) or without co-occurring verbal means (Stolle & Pfeiffer, 2023/this issue).

All in all, these findings show that eyebrow contractions are not usually used in isolation, but together with other vocal, verbal and bodily resources. In addition to the particular multimodal gestalt of which they are a part, their sequential placement is also decisive for the interactive work they accomplish. Consequently, they constitute a versatile resource serving various communicative functions: from the projection of a negative evaluation or epistemic challenge to the initiation of repair and the contextualisation of delicate actions. What they seem to have in common is the marking of problematic aspects of the interaction. Our study aims to extend the aforementioned research by investigating frowns in a different conversational context: argumentative decision-making in children's interactions.

2.2 Opposition in argumentative interactions

The activity of decision-making has been examined in various contexts, such as planning meetings in workplaces (Stevanovic, 2012, 2013; Stevanovic & Peräkylä, 2012; Huisman, 2001), in healthcare interactions (Stivers et al., 2018; Stivers, 2002) or in group discussions among children (Klein & Miller, 1981; Heller, 2018; Mundwiler & Kreuz, 2018).

Argumentative decision-making is constituted by the participants establishing an open problem or dissent (Quasthoff et al., 2017). In contrast to other discursive practices, the preference for agreement (Pomerantz, 1984) is usually suspended, allowing oppositional actions to be produced without delay (Goodwin, 1987; Kendrick & Holler, 2017). Furthermore, actions such as proposing (Ste-vanovic, 2012; Mondada, 2015; Stivers & Sidnell, 2016), stating (Stivers, 2002), negotiating (Stivers, 2002; Kreuz & Luginbühl, 2020), justifying (Kyratzis et al., 2010), contradicting (Maynard, 1986; Goodwin, 1987; Spranz-Fogasy, 1986), rejecting/mere refusing and accepting/complying (Stevanovic, 2012; Goodwin & Cekaite, 2018), pleading objections (Goodwin & Cekaite, 2018) or (critical) questioning (Koshik, 2003, 2005) are common in this activity type.

This paper focuses on the two actions of contradicting and putting something into question. From Hutchby (1996), we understand these actions as opposi-tional since they 'formulate[ ] the prior action as an arguable' (Hutchby, 1996: 23). This way, the former action is retrospectively contextualised as problemat-ic. Since the proposal or claim is not approved but contradicted or put into question, the progressivity of the decision-making process comes to a halt.

Contradicting often comprises adversative elements on the verbal level, for example, negative particles (e.g. 'no', 'not'), which are often used in format-tied turns ('I would take X' – 'I would NOT take X', see Goodwin, 1990) or adversa-tive connectors (e.g. 'but', see Spranz-Fogasy, 1986). When the speaker justifies his/her counter-position, his/her position may either remain highly implicit or be stated explicitly. The recipient can maintain his/her position either by ex-panding it through justification (Brumark, 2008) or overtly contradicting the other's position (Goodwin, 1990). Recipients can also give in to or be con-vinced by the speaker's arguments and agree with his/her (op)position.

Opposition can also be established by putting something into question. This type of oppositional action entails interrogatively formatted utterances which not only serve as requests for further information or argumentative support, but also indicate the speaker's own position (see Heritage, 2002, for negative interrogatives) as somehow different from that of the co-participant's. For instance, by repeating a prior turn with raising intonation, speakers mark specific discourse elements as problematic and perform a 'complaint [ ] and challenge' (Tracy & Robles, 2009: 134; Goodwin, 1990; Koshik, 2005) or surprise (Rossi, 2020; Selting, 1995), thereby displaying disaffiliation (Steensig & Drew, 2008; Tracy & Robles, 2009).

Affective and epistemic stances (Ochs, 1996; Du Bois, 2007; Du Bois & Kärkkäinen, 2012; Goodwin et al., 2012) serve as crucial meaning components of oppositional actions. Participants draw on various multimodal resources to contextualise their action as more or less critical, as Tainio (2012) shows for prosodic imitation in teachers' repetitions of students' talk. However, facial resources such as frowning (Kaukomaa et al., 2014), thinking displays (Heller, 2021), or rolling the eyes (Clift, 2021) also play a crucial role in displaying a critical stance. Based on previous research on facial expressions (Section 2.1), this study focuses on the role of eyebrow contractions in children's decision-making processes.

3. Data and Method

Our study is based on a data corpus (comprising a total of 73 minutes) consist-ing of 16 videotaped peer interactions among three to five children from grades 3, 4 and 6. Decision-making processes were elicited by providing the children with two fictitious problem scenarios they had to negotiate. The first problem concerned a shipwreck that required the children to jointly agree on three of eight items they considered essential for survival on a desert island (see also Kreuz & Luginbühl, 2020); the second scenario entailed a moral dilemma which required the children to make a joint decision on how to handle this delicate situation. The children sat in a semicircle around a table and were recorded by one camera.

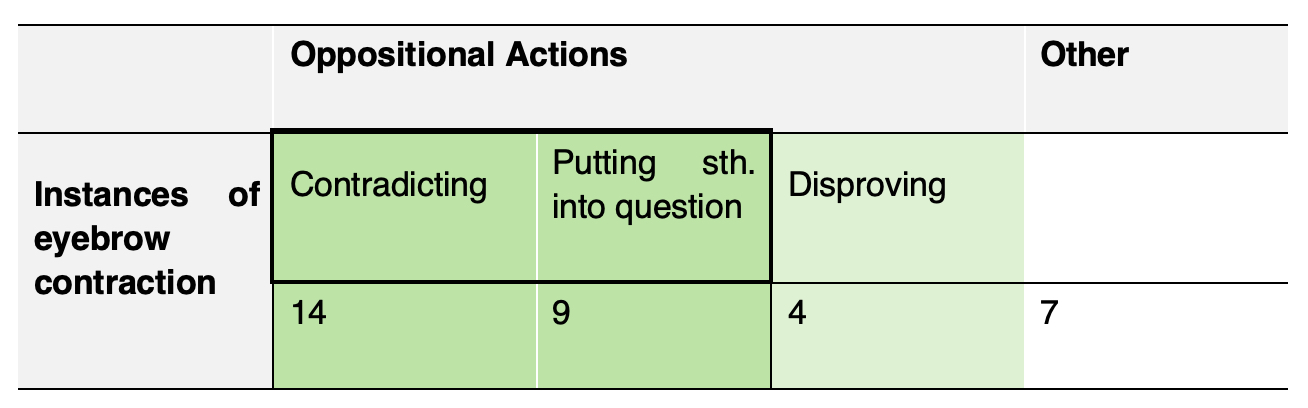

For data preparation, the recordings were annotated by two independent analysts with respect to all eyebrow contractions performed by the speaker. An initial analysis focusing on the social actions revealed that eyebrow contractions occur in various conversational actions (Table 1): in oppositional actions such as contradicting, questioning and disproving, and in other actions such as making a proposal or signalling consent.

Table 1. Eyebrow contractions in children's decision-making.

As Table 1 shows, eyebrow contractions are particularly prevalent in oppositional actions. For this reason, our analysis focuses on oppositional actions, in particular on contradicting and putting something into question. Cases of disproving were excluded, since they entail the production of big packages and therefore differ in their temporal unfolding. Thus, a collection of 23 instances was compiled, which constitutes the data basis of this study. Note that the specification of the respective social action was not predetermined but was the result of a circular analysis process: the initial categorisation of instances in the preparation of the corpus was re-examined and modified if necessary in the course of the in-depth analyses. All instances were analysed in detail, using multimodal interaction analysis (Goodwin, 2000). This methodological approach builds, among other things, on insights evolved from conversation analysis (Sacks, 1995; Sidnell & Stivers, 2013) and 'takes into account simul-taneously the details of language use, the semiotic structure provided by the […] material world, the body as an unfolding locus for the display of meaning and action, and the temporally unfolding organization of talk-in-interaction' (Goodwin, 2000: 1517).

In line with Mondada (2014), we conceive of critical stance displays as 'complex multimodal gestalts' composed of multiple finely coordinated resources, 'mobilized and packaged in an emergent, incremental, dynamic way' (p. 140). Thus, our analysis focuses on the type of eyebrow movement (i.e. contraction combined with raising or lowering), its duration and combination with other facial (e.g. forehead, mouth and nose) and bodily resources (e.g. gestures, body posture, gaze), its turn position (pre/post-turn, accompanying verbal speech) and the visual perception by the recipient. Beyond that, we consider prosodic designs of verbal utterances as a component of the multimodal critical stance displays.

To show how multimodal displays of critical stance contribute to the contextualisation of conversational actions, we also examine their interactional trajectories. In particular, we consider the recipient's response; in our multiparty interactions, this can be produced either immediately after the speaker's utterance or sometimes, if another participant intervenes first, at later point in the interaction.

The transcription follows the GAT2 conventions developed by Selting et al. (2011).1 Additionally we adopted the multimodal annotation system proposed by Mondada (2018). For the depiction of facial expressions, we inserted still images captured from the video recordings. For privacy reasons, the children's names and still images were anonymised, thus we captured only the most relevant facial traits and bodily features. In the following, we present prototypical examples of critical stance displays in children's oppositional actions.

4. Multimodal Displays of Critical Stance in Different Oppositional Actions

During oppositional actions, children may use clusters of multimodal resources to display different degrees of criticism toward a previously stated position. These clusters comprise the degree of eye opening, gaze direction, ten-sions in the mouth and/or nose area, prosodic contours and eyebrow contractions while simultaneously lowering/raising them. We refer to these multimodal gestalts as critical stance displays. In what follows, we present two prototypical examples of contradicting (Section 4.1) and questioning (Section 4.2), each showing subtle differences in the degree of criticism and the interactive trajec-tories. The sequence of the four examples is organised in such a way as to reveal an increasing degree of confrontationality of oppositional actions.

4.1 Critical stance displays in acts of contradicting

Acts of contradicting may be accompanied by brief eyebrow contractions. This is consistently associated with lowering the inner corners of the brows, (slightly) squinting the eyes and tensions in the mouth and/or nose area. Optionally, prosodic markers may be used to intensify the speaker's critical stance. Such multimodal critical stance displays generally enhance the criticism expressed in the verbal contradiction. However, microscopic changes in the eyebrow movement – raising the inner brows – can induce a shift in the speaker's stance from rather factual-critical to rather concerned-critical. In this way, the confrontationality of the critical stance display can be mitigated to invite recipients to reconsider their position and/or to justify it more convincingly.

The following sequence unfolds between the third graders Walid, Carolin, Moritz and Fiete and is taken from the very beginning of their negotiation of the shipwreck scenario (Section 3). Extract 1 shows how Carolin2 contracts her eyebrows to display a mild critical stance toward Fiete's proposal, leading Fiete to further support his opposite standpoint in the further course of interaction.

Extract 1.

Open in a separate window

Context. Moritz is the first to state which items he would choose (i.e. flashlight, first aid kit and tent, l. 047), and he receives approval from Carolin (l. 048). Fiete, however, rejects Moritz's selection ('no', l. 049), suggests the mobile phone as essential and justifies its relevance: 'no look one needs the mobile phone PTCL/to call' (l. 049f.). Even before Fiete produces a reason, Moritz agrees with him, although this agreement is uttered rather softly (l. 050).

Contradicting with mild critical stance display. After Walid subsequently raises a question concerning the task (l. 053), Carolin, in overlap with Moritz's ratification, turns her body to Fiete and contradicts his proposal (l. 055). Although she does not explicitly refuse the mobile phone, this utterance involves a verbal rejection, marked by the adversative connector 'aber' ('but') and prosodically by raising her voice and the strong emphasis on the evaluative term '!WICH!tigste' ('the most important', l. 055). In this way, she reveals that, in her view, the mobile phone does not meet the selection criteria. While the rejection of the mobile phone remains rather implicit, Carolin enhances its critical import through the finely coordinated integration of bodily and, in particular, facial resources, yet in a rather 'mild' and emotionally concerned way.

Thus, immediately at the beginning of her turn, she contracts and lowers her eyebrows (#1). Furthermore, she squints her eyes, tightens her upper lip and wrinkles her nose. The wrinkling of the nose has been described by Hübscher et al. (2019) as a bodily resource for 'distancing oneself from [...] unpleasant, uncertain [situations]' (p. 376). Eventually, the verbal, prosodic and facial re-sources applied culminate on the strong focus accent when Carolin accom-plishes an embodied summons (Kidwell, 2006) and lifts her head slightly (#2) towards Fiete, who as a consequence directs his gaze at Carolin (#3). Note that the rigid position of Carolin's upper body position (resting the arms on the table, refraining from hand movements) directs the recipient's attention to her face, thereby enhancing its perceptibility (Heller, 2021). Up to this point, the critical stance display emerges incrementally and its intensity increases gradually. Immediately after the concurrence of all resources at the culmination point (see multimodal compaction zone, Stukenbrock, 2018: 40), the eyelids and the nose return to resting position. Only the upper lip is further tightened until the end of Carolin's turn. Additionally, the eyebrows remain contracted, but after the point of culmination has passed, Carolin raises the inner brows and lowers them briefly solely on the first syllable of 'mitnehmen' ('taking with you', l. 055, #3). With this change in eyebrow movement, a transformation from a (rather) factual to a (rather) concerned critical stance manifests. In this way, she conveys her meta-discursive position of taking the task seriously and pro-ceeding attentively in the selection of items in an emotionally involved manner, that is, full of concern that this maxim may be disregarded in the group's decision-making process. This qualitative shift in Carolin's affective stance mitigates the confrontationality of her opposition.

Interactive trajectory. The interactive consequences of this multimodal stance display only become visible in the further course of the conversation. After an intense discussion of the objects Moritz had already introduced at the beginning of the sequence (i.e. flashlight, first aid kit and tent), Fiete resumes the discussion about the mobile phone (l. 099f.). Since he directs his gaze to Carolin at the end of his turn, his orientation to Carolin, as the opponent who needs to be convinced, is evident (see Auer, 2017: 8ff.). In contrast to his first attempt (l. 049f.), he elaborates his argumentation and presents an argument that qualifies the phone over the flashlight: 'I would take the mobile phone/and then you can make light with it' (l. 099f.). In this way, he refutes the necessity of the flashlight in favour of the phone. His elaboration leads Carolin to finally accept his proposal (l. 106). Hence, what Extract 1 reveals is that Carolin's mild critical stance display invites Fiete to substantiate and elaborate an argument.

Acts of contradicting may also be accompanied by critical stance displays that serve to project the speaker's elaboration of his/her own position. We demonstrate this case with Extract 2. Here, the speaker's stance is more confrontational: compared to Extract 1, the speaker's contradiction and counterclaim are more explicit and assertive. Furthermore, the facial expression that signals the critical stance is not modified but held, so that the criticism is not mitigated through displays of affective concern.

While discussing the shipwreck scenario, Kim assumes an oppositional position relative to her co-participant Fabrizio. Because Greta also contradicts Fabrizio, Kim has to compete for the right to speak in order to get the opportunity to expose and/or elaborate her own position.

Extract 2.

Open in a separate window

Context. After Fabrizio has stated his personal choice (flashlight, knife and matches, l. 090), Greta vehemently rejects his proposal using a high-pitched and forcefully or emphatically (Selting, 1994) expressed negation: 'NEI:[N];' ('no', l. 091), indicating that she will further elaborate her position (see Ford et al., 2004, for no-plus turns in topic proffers).

Contradicting with a strong critical stance display. Even before Greta completes her negation, Kim interrupts her by producing another emphatic contradiction (l. 092), thus verbally and prosodically displaying a strong critical stance towards Fabrizio. Additionally, she contracts her eyebrows and tightens her upper lip (#1). Kim also squints her eyes slightly and puffs out her cheeks. These two components start successively and do not persist throughout the entire turn, so the verbal, prosodic and bodily resources culminate only momentarily. Kim's gaze is constantly directed at the handout (even beyond her turn), which seems to mitigate the intense affective and confrontational charge of her verbal contradiction. With the beginning of her turn, however, Kim also changes her body posture and sits up, which signals her vigilance and readiness to defend her position. Due to the seating arrangement, this change in posture and the emergence of the whole gestalt occurs in the o-space (Ciolek & Kendon, 1980: 243; Kendon, 1990) shared by the children. Consequently, it is at least to some extent visually perceptible to Fabrizio, even if he is not directly looking at Kim. While elaborating her contradiction, Kim still tightens her mouth and dissolves this only just before finishing her counter-proposal (i.e. matches, blanket and flashlight, l. 094). Consequently, her multimodal stance display is still visible in the following turn.

Interactive trajectory. The critical stance display in this sequence serves here to indicate the speaker's rejection (as in Extract 1) and to project his own elaboration of a counter-proposal. Kim's formatting of her assertions, her sitting up and the interruptions of her co-participants (l. 091f.; 093f.) reveal that she is acting quite confrontationally, aiming to maintain the turn in order to persuade the other group members of her position. The constant focus of the gaze on the handout also provides evidence for Kim not intending to give someone else the turn (see Kendon, 1973: 63). Greta tolerates Kim holding the floor and abandons her utterance (l. 093). Furthermore, the children give Kim sufficient conversational space to bring forth her argumentation (l. 094–104). Thus, the analysis of Extract 2 demonstrates how the composition and unfolding of the critical stance display enhance the confrontational charge of Kim's opposition-al move and enable her to keep the floor and bring forth a counter-proposal. However, as Kim proceeds, she adds a barely understandable 'I think' (l. 095) in a low voice and interrupts her turn with a help-seeking look (l. 096f.) when she has difficulties in producing her argument. She thus displays epistemic uncertainty and ultimately fails to be convincing (l. 105).

The analyses showed that children combine resources from multiple modalities to display their critical stance. In contradictory actions, these multimodal displays serve to reinforce the verbally marked ('but', 'no') opposing position expressed by the contradiction. In particular, the contraction and lowering of the eyebrows, the (slight) squinting of the eyes and various forms of tension in the mouth, and often also in the nose area, are recurring and thus stylised means of indicating doubt and criticism. Since the slightest changes in the eyebrow movement can cause a transformation of the speaker's affective stance (e.g. from (rather) factual-critical to (rather) concerned-critical as in Ex-tract 1), the eyebrows are considered to be of crucial importance. Supplemen-tary prosodic resources, such as emphatic contours (Selting, 1994), are used to calibrate and intensify the displayed stance (see also Tainio, 2012; Couper-Kuhlen, 2004). Regarding the temporal unfolding, the analysis further revealed that verbal, prosodic and bodily resources within contradictions generally commence simultaneously, although the bodily resources may unfold incrementally. The specific multimodal stance displays calibrated the children's oppositional actions in such a way that they occasioned different interactive trajectories. 'Mild' displays of critical stance, followed by expressions of affec-tive concern, invited the recipient to elaborate his argumentation and thus enabled a more detailed examination of a proposal without rendering the decision-making confrontational (Extract 1). Multimodal gestalts of strong criticism projected the speaker's rejection and counter-proposal and thus contributed to a more confrontational framing (Extract 2).

4.2 Critical stance displays in acts of questioning

A second environment of critical stance displays are actions by which children put (aspects of) a previously stated position into question. In contrast to acts of contradicting, which usually mark the opposition on the lexical level, the oppositional import in acts of questioning depends on interrogative syntax as well as prosodic and bodily resources. In acts of questioning, eyebrow contractions (combined with either lowering or raising the brows) are consistently accom-panied by prosodic cues that indicate the speaker's affective stance. Another component is what we will call confrontational gaze. With this type of gaze the current speaker addresses a previous speaker as the target of their opposition. Optionally, further embodied resources such as inflating the nasal wings or raising the upper lip are used.

In Extract 3, the speaker uses these resources to hand over the epistemic responsibility for handling the critical aspect to the recipient. The multimodal display of critical stance culminates at the end of the speaker's turn and thus renders the action as highly confrontational. By holding the confrontational gaze beyond the turn, the speaker demands a justification from the recipient. Furthermore, the speaker's stance is not only critical, but also reproachful in that it indicates negative surprise about the previous speaker's proposal.

The following analysis shows how Kim puts Greta's proposal of three survival items into question. By contracting her eyebrows and directing a confrontational gaze at Greta, Kim displays an intense critical and affectively charged stance and addresses Greta as the recipient of her reproach.

Extract 3.

Open in a separate window

Context. Right from the beginning of the sequence, Kim argues for the matches (l. 045–51) and re-establishes them as an essential item (l. 056). Beyond that, epistemic certainty markers such as 'auf jeden fall' ('definitely') and the use of deictic gestures (tapping with the index finger on the matches) emphasises the relevance Kim attributes to the item. Subsequently, Greta proposes her list of items, which consists of the blanket, the flashlight and the tent. After a response of the group remains absent, the list is expanded by a justification ('because you need the tent', l. 063), which then overlaps with Kim producing an oppositional action and putting Greta's pro-posal into question ('not the matches', l. 064).

Questioning with reproachful-critical stance display. Beginning with the nega-tive particle 'nicht' ('not'), Kim conveys opposition3 at the earliest possible moment of the turn (Goodwin & Goodwin, 2001) and further indicates a breach of her expectation by prosodic cues (Selting, 1994; 1995): the focus accent on the first syllable of 'STREICHhölzer' ('matches') as well as the final lengthening and the rising intonation indexes negative surprise about Greta's disregard of the matches and thus contextualises the reproachful meaning of the questioning. The entire unfolding multimodal gestalt comprises multiple contextualisation cues for her reproachful-critical stance: while still gazing at the handout at the beginning of her turn, Kim orients to the matches by naming and simultaneously pointing at them (l. 064). Kim then turns her head and shifts her gaze with open eyes to Greta, making her the addressee (Auer, 2017) of the critical question. In doing so, she contracts her eyebrows and inflates her nasal wings while saying 'matches'. This is where various multimodal resources come together as a complex multimodal gestalt in a culmination point (#1). Due to the culmination of all these resources at the end of the turn and the maintenance of the body posture and the eyebrow contraction which are sustained throughout the pause, a mitigation of the critical stance is prevented. The gaze towards the recipient plays a decisive role in this. The usual preference organisation entails that in dispreferred responses the gaze is averted to mitigate the disaffiliative import of the action (Haddington, 2006). However, this normal association between dispreferred actions and turn formats can be in-verted (Kendrick & Holler, 2017). When dispreferred actions are produced in preferred turn formats – staring at the recipient and maintaining eye contact – this does not mitigate, but instead amplifies the critical and confrontational im-port of the action (see Kendrick & Holler, 2017: 28). We therefore refer to this practice as confrontational gaze. The confrontational charge of the action is accompanied by the speaker rejecting the responsibility for dealing with the critical item and assigning the responsibility to the recipient. Although Greta is looking at the handout, it is expectable that Kim's gaze shift and turn of her head which select Greta as the next speaker are at least peripherally visible for Greta.

Interactive trajectory. This results in a longer pause (l. 065) in which the eyebrow contraction is dissolved. While Greta does not immediately take over the next turn, Kim's facial resources are transformed into a smile (l. 065) before she again argues for the matches (l. 066). After first sticking to her initial position (the flashlight, l. 067), Greta then abandons it and even provides reasons for Kim's choice ('then you just make yourself a torch with the matches', l. 069). Thus, Kim's multimodal critical stance display rejects her own epistemic responsibility for dealing with the critical item and establishes a strong demand for the recipient to take on this task.

Acts of questioning can also be accompanied by multimodal critical stance displays that cast a proposal of another participant as not worthy of discussion. Such displays entail contracted eyebrows, wide opened eyes and confrontational gaze, and they also culminate at the end of the speaker's turn. In con-trast to Extract 3, however, additional resources such as raised eyebrows and confrontational 'or what' tags increase the criticism to a degree that the recipient refrains from further discussion of the disputed item.

In Extract 4, Damira makes two suggestions for a third item. One of the sugges-tions is taken up by Sila and vehemently called into question.4 During the sec-ond questioning, the contracting of the eyebrows occurs. Again, the dispre-ferred action is accompanied by the speaker's (Sila's) gaze at the recipient and wide opened eyes. In contrast to Extract 3, however, the eyebrows are raised rather than lowered and the utterance is produced with a dismissive intonation contour, which increases the degree of confrontation. The act of questioning is thus even more affectively charged and turned into a personal attack.

Extract 4.

Open in a separate window

Context. After the children have agreed on two items, Damira, who is standing at the table, suggests two objects for the third item to be chosen: she points to the knife and the matches (l. 075). The first proposal, 'knife', is immediately taken up by Sila, who produces a polar question (l. 076: 'a knife?'). Its multimodal design conveys that this question is not a request for confirmation or repair initiator but instead serves to indicate the speaker's lack of commitment to the propositional content: the final syllable of 'MESse::r,' ('knife') is lengthened and produced with first a falling and then rising intonation contour, con-veying negative surprise and indignance. Furthermore, the first syllable of 'knife' ('MES') is temporally aligned with a slap on the table with the open hand palm up, a gesture which is often used to solicit a reason (Streeck, 2007; Schönfelder & Heller, 2019). Beyond the end of the turn-constructional unit, the gaze is directed at Damira. This multimodal packaging contextualises the action as putting a proposal into question. The questioning is expanded in line 078 where, through another and more spacious trajectory of a palm up gesture, a reason is given, which is, however, at the same time invalidated by an ironic keying (Goffman, 1974). The communicative function of the held palm up, with which speakers usually solicit a reason from their counterpart, is here turned into its opposite: by producing the gesture not in combination with a request for a reason but the giving of a reason, the speaker indicates that the reason (l. 078: 'so that you can kill him') is evaluated as invalid. The change in body posture – a distancing leaning back – and confrontational gaze (see Section 4.2.1) toward the proponent also serve to contextualise the irony. In the present case, the confrontational framing is additionally reinforced by the rather blunt tag 'or what' which suggests that no valid reason exists.

As a response, Damira produces a format-tied (Goodwin, 1990) counter-argument (l. 080: 'so that you…'). The turn-final 'vielleicht' ('perhaps') is not used to convey epistemic uncertainty; rather, the turn-final placement, the lengthening of the final syllable and the rising intonation mark the propositional content, that is, the reason, as obvious. The obviousness of this reason – and thus the dispensability of questioning – is additionally indicated by the raising of the eyebrows and the shaking of the head. Furthermore, Damira stares at her opponent and thus reciprocates the confrontational gaze. Together, these resources contribute to the confrontational charge of the response and serve to reject Sila's attack on her epistemic rights.

Questioning with an ironic-critical stance display. Already during Damira's turn, Sila leans forward, brings her hand briefly to her chin and then crosses her arms, adopting a dismissive posture. In addition, her gaze aversion signals that she has taken the turn (Auer, 2017). Next, she gazes upwards and raises her eyebrows, then contracts her brows and widens her eyes. Ignoring Sejla's reference to the flashlight (l. 081) and Faris' multimodal response (l. 083), she then expands her questioning by demonstrating the function of the knife invoked by Damira in an exaggerated and ironic way (l. 082): the four stabbing motions are accompanied by a dull gaze and mockingly produced moans. In addition, Sila inflates her nasal wings, raises her upper lip and contracts her brows (#1). This dense cluster of multimodal resources is held for almost the entire enactment (#2), with the contraction of the eyebrows outlasting the other resources and thus being particularly visible. Indeed, the eyebrow contraction is seen not only by Damira, who turns her gaze to Sila, but also by Faris. To-gether with the other facial, prosodic and bodily resources, the contracted and raised eyebrows amplify the speaker's ironic-critical stance and contribute to making a mockery of Damira's reasoning. At the same time, this has the effect of denying the proponent the ability to think rationally and thus attacks her personally. The contracted brows are dissolved just before a second, even more dismissive, 'or what' tag. The high degree of confrontation is reinforced by a shoulder shrug, slapping the hand palm up on the table and maintaining the confrontational gaze at Damira. This culmination of resources has the effect of making the question appear unanswerable and preventing further discussion, which also becomes apparent in the further course of the conversation.

Interactive trajectory. After both girls have looked at each other for one second, Damira is the first to avert her gaze. Due to the fact that Damira does not claim the next turn, her gaze aversion may be interpreted as 'giving up'. Instead of Damira, Sejla becomes the next speaker and suggests choosing the flashlight (l. 086), which is confirmed by Sila (l. 087). Damira's proposal, the knife, is thus dropped.

As in Extract 3, the culmination of the critical stance display at the end of the turn increases the degree of confrontation. The open 'presentation' of the contracted eyebrows during the confrontational gaze plays a significant role in this. Unlike in Extract 3, however, the 'or what' tags do not make the proponent responsible for further justification, but instead deny her the opportunity to provide reasons, in this way preventing further discussion of the disputed object.

The analyses of Extracts 3 and 4 demonstrate that the confrontational import of acts of questioning can be aggravated by multimodal displays of critical stance. While the action of putting something into question itself indicates that the speaker's position is somehow different from the co-participant's (e.g. 'not the matches'), the multimodal display reinforces the recipient's criticism and indicates that specific elements of the recipient's position are evaluated as problematic. The emerging multimodal gestalts entail eyebrow contractions (combined with either downward or upward movements), inflation of the nasal wings and gaze with open eyes at the recipient. Furthermore, prosodic resources may indicate the speaker's negative surprise.

The stance displays can either occur rather late in the turn (Extract 3) or in turn-initial position (Extract 4). In both cases, the speakers shift their gaze to the recipient in the course of the turn and hold it until the tension is released, such as when the recipient averts her gaze or the speaker starts to smile. By holding the gaze beyond the turn, the degree of confrontation increases: the challenged recipient is addressed directly (see confrontational gaze) and made responsible for the critical discourse element through the hold of the multimodal gestalt. The multimodal gestalts differ, however, in terms of their quality and degree of confrontation. They contextualise the act of questioning as either reproachful or highly ironic. Depending on their particular quality they either shift the epistemic responsibility to deal with the counter-position to the recipient (Extract 3) or attacked the recipient personally and deny her the opportunity to support her position (Extract 4).

5. Conclusion

Based on previous research on how facial expressions bring about subtle aspects of interactional conduct, this study examined multimodal displays of critical stance that entailed eyebrow contractions as a crucial component. Using a corpus of children's argumentative decision-making, we described different multimodal gestalts of critical stance displays in oppositional acts of contradicting and questioning and traced their interactional trajectories.

Our analyses of the 23 instances in our corpus demonstrated that the two op-positional actions are accomplished through distinct clusters of resources, embodying the speaker's mild critical stance (Extract 1), strong critical stance (Extract 2), reproachful-critical stance (Extract 3) or ironic-critical stance (Ex-tract 4). In the case of contradicting, the contraction and lowering of the eyebrows, the (slight) squinting of the eyes and the tightening of the mouth and/or nose area combined in recurring, incrementally unfolding resource cluster. A microscopic change in movement (raising the inner corners of the brows) caused a qualitative shift in the speaker's affective stance and signalled affective concern, mitigating the confrontational import of the display. In comparison, the display was constituted somewhat differently in the context of putting something into question. Here, the eyebrow movement was more variable, since the eyebrows can be both raised and lowered during contraction without affecting the quality of the affective stance. Moreover, inflating the nasal wings and leaving the eyes open or even opening them wide are stylised resources in this respect. In both actions, however, prosodic contours can be employed to increase the confrontational meaning of the action. Likewise, we found that gaze was used to calibrate the degree of confrontation. While speakers commonly avert their gaze when contradicting (directing it instead to the handout on the table) and this way mitigating the confrontational import, their gaze is often directed to the recipient, even beyond the turn, when putting something into question. As a consequence, and as the single resources culminate in turn-final position, the critical and confrontational import is increased significantly (see also Andries et al., 2023).

Depending on the distinct clusters of resources and the duration of the multimodal gestalt, a more or less intense critical stance display is thus created. Considering that even the smallest changes in the calibration of resources may change the intensity (and possibly also the quality) of the affective stance of the speaker, we argue that the different manifestations constitute a continuum from mildly critical to highly confrontational critical stances. The analyses demonstrated that the different displays of criticism occasion different interactive trajectories of decision-making. They were followed by an elaboration of an argument (either by the recipient or the speaker, as in Extract 1 and 2), a justification and the abandonment of one's position (Extract 3) or the termination of the discussion of a specific item (Extract 4).

In line with previous research (Kaukomaa et al., 2014; Li, 2021), our analysis thus confirms that eyebrow contractions serve to mark problematic aspects of an interaction. In contrast to the cases studied by Kaukomaa et al. (2014), however, our examples show that eyebrow contractions are not only used in turn-initial position, but also in other turn positions to retrospectively point out problematic aspects of a previous action. They help to slow down decision-making and to make a seemingly unproblematic aspect the subject of critical discussion. Furthermore, while Kaukomaa et al. (2014: 145) observed that 'disaffiliations expressed without frowning were often more straightforward' and that 'turn-opening frowns conveyed that the speaker was still “contemplating”' our analysis reveals that the degree of confrontation of the oppositional turn strongly depends on the speaker's gaze behaviour. On the one hand, the gaze aversion help to mitigate the confrontational potential of the action. On the other hand, when the gaze remained directed toward the recipient, the confrontational charge was amplified, as the critical stance display was pre-sented directly and openly. This confrontational gaze was part of an inversion of the usual preference organisation (Kendrick & Holler, 2017): the dispreferred action was produced in a format typically used for preferred actions. As a consequence, the critical and confrontational import of the action was not mitigated but instead amplified.

Altogether, our study shows that eyebrow contraction is used in different social actions and forms an important element of more or less stable action-specific clusters of multimodal resources. As one element of embodied critical stance displays, eyebrow contractions help to indicate that the other's position has 'touched' or 'affected' the speaker and provoked a critical response. In com-parison to the transient quality of verbal resources, these multimodal gestalts entail particular affordances (see also Marrese et al., 2021): they can be held, averted or openly shown to the recipient. These affordances allow speakers to calibrate the criticism and the confrontational import of their oppositional action. By mitigating or aggravating oppositional actions, they thus contribute to the management of affectivity and epistemic responsibility in decision-making processes.

Acknowledgements

We thank the children who participated in the study for the opportunity to gain videographic insights into their peer group interactions. Further thanks go to Alexandra Groß, Carolin Dix, the two anonymous reviewers and the members of the Child Interaction Group for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

References

Andries, F., Meissl, K., de Vries, C., Feyaerts, K., Oben, B., Sambre, P., Vermeerbergen, M., & Brône, G. (2023). Multimodal stance-taking in interaction – A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Communication, 8:1187977. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1187977

Auer, P. (2017). Gaze, addressee selection and turn-taking in three-party interaction. Interaction and Linguistic Structures, 60, 1–32.

Bavelas, J., Gerwing, J., Healing, S. (2014). Including facial gestures in gesture-speech ensembles. In M. Seyfeddinipur & M. Gullberg (Eds.), From Gesture in Conversation to Visible Action as Utterance. Essays in honor of Adam Kendon (pp. 15–34). Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Brumark, Å. (2008). "Eat your Hamburger!"—"No, I don't Want to!". Argumentation and Argumentative Development in the Context of Dinner Conversation in Twenty Swedish Families. Argumentation, 22, 251–271.

Cekaite, A. (2012). Affective stances in teacher-novice student interactions: Language, embodiment, and willingness to learn in Swedish primary classroom. Language in Society, 41, 641–670.

Chovil, N. (1991). Discourse‐oriented facial displays in conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 25(1) 163–194.

Ciolek, T. M., & Kendon, A. (1980). Environment and the Spatial Arrangement of Conversational Encounters. Sociological Inquiry, 50, 237–271.

Clift, R. (2021). Embodiment in Dissent: The Eye Roll as an Interactional Practice. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 54(3), 261–276.

Cook, H. M. (2014). Language socialization and stance-taking practices. In A. Duranti, E. Ochs & B.B. Schieffelin (Eds.), The handbook of language socialization (pp. 296–321). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2004). Prosody and sequence organization in English conversation. The case of new beginnings. In E. Couper-Kuhlen & C. Ford (Eds.), Sound patterns in interaction (pp. 335–376). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Darwin, C. (1872). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. New York: Philosophical Library.

Du Bois, J. W., & Kärkkäinen, E. (2012). Taking a Stance on Emotion: Affect, Sequence, and Intersubjectivity in Dialogic Interaction. Text & Talk, 32(4), 433–451.

Egbert, M. (1993). Schisming: The Transformation from a Single Conversation to Multiple Conversations. Dissertation. University of California Los Angeles.

Ekman, P. (1979). About brows: emotional and conversational signals. In M. van Cranach, K. Foppa, W. Lepenies, & D. Ploog (Eds.), Human Ethology (pp. 169–249). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ekman, P. (2007). Emotions Revealed. New York: Henry Holt.

Feyaerts, K., Rominger, Ch., Feyaerts, K., Rominger, Ch., Lackner, H.K., Brône, G., Jehoul, A., Oben, B., Papousek, I. (2022). In your face? Exploring multimodal response patterns involving facial responses to verbal and gestural stance-taking expressions. Journal of Pragmatics 190, 6–17.

Ford, C. E., Fox, B. A., & Hellermann, J. (2004). “Getting past no”: Sequence, action and sound production in the projection of no-initiated turns. In E. Couper-Kuhlen & C. E. Ford (Eds.), Sound Patterns in Interaction: Cross-linguistic Studies from Conversation (pp. 233–269). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Goodwin, C. (2000). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 32, 1489–1522.

Goodwin, C. (2018). Co-Operative Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goodwin, M. H., & Goodwin, C. (1986). Gesture and coparticipation in the activity of searching for a word. Semiotica, 62(1-2), 51–75.

Goodwin, M. H., & Goodwin, C. (1987). Children's arguing. In: S. Philips, S. Steele, & C. Tanz (Eds.), Language, Gender, and Sex in Comparative Perspective (pp. 200–248). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goodwin, M. H. (1990). He-said-she-said. Talk as social organisation among black children. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Goodwin, M. H., & Goodwin, C. (2001). Emotion within Situated Activity. In A. Duranti (Ed.), Linguistic Anthropology: A Reader (pp. 239–257). Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Goodwin, M, H., & Alim, H. S. (2010). “Whatever (Neck Roll, Eye Roll, Teeth Suck)”. The Situated Coproduction of Social Categories and Identities through Stancetaking and Transmodal Stylization. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 20(1), 179–194.

Goodwin, M. H., Cekaite, A., & Goodwin, C. (2012). Emotion as Stance. In A. Peräkylä & M.-L. Sorjonen (Eds.), Emotion in interaction (pp. 16–41). Ox-ford: Oxford University Press.

Goodwin, M.H.; Cekaite, A. (2018): Embodied family choreography. Practices of control, care, and mundane creativity. London: Routledge.

Haddington, P. (2006). The organization of gaze and assessments as resources for stance taking. Text & Talk, 26(3), 281–328.

Heller, V. (2018). Embodying epistemic responsibility. The interplay of gaze and stance-taking in children's collaborative reasoning. Research on Children and Social Interaction, 2(2), 262–285.

Heller, V. (2021). Embodied Displays of “Doing Thinking.” Epistemic and Interactive Functions of Thinking Displays in Children's Argumentative Activities. Frontiers in Psychology, 12:636671, 1–21.

Heritage, J. (2002). The limits of questioning: Negative interrogatives and hostile question content. Journal of Pragmatics, 34(10-11), 1427–1446.

Heritage, J., & Raymond, G. (2005). The Terms of Agreement: Indexing Epis-temic Authority and Subordination in Talk-in-Interaction. Social Psychology Quarterly 68(1),15–38.

Hübscher, I., Vincze, L., & Prieto, P. (2019). Children's signaling of their uncertain knowledge state: prosody, face and body cues come first. Language, Learning and Development, 15(4), 366-389.

Huisman, M. (2001). Decision-Making in Meetings as Talk-in-Interaction. International Studies of Management & Organization, 31(3), 69–90.

Hutchby, I. (1996). Confrontation Talk: Arguments, Asymmetries, and Power on Talk Radio. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Iwasaki, S. (2015). Collaboratively organized stancetaking in Japanese: Sharing and negotiating stance within the turn constructional unit. Journal of Pragmatics, 83, 104–119.

Kääntä, L. (2014). From noticing to initiating correction: Students' epistemic displays in instructional interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 66, 86–105.

Kaukomaa, T., Peräkylä, A., & Ruusuvuori, J. (2014). Foreshadowing a problem: Turn-opening frowns in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 71, 132–147.

Kendon, A. (1973). The role of visible behavior in the organization of social interaction. In M. Cranach & I. Vine (Eds.), Social Communication and Movement: Studies of Interaction and Expression in Man and Chimpanzee (pp. 29-74). New York: Academic Press.

Kendon, A. (1990). Conducting interaction. Patterns of behavior in focused encounters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture. Visible action as utterance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kendrick, K. H., & Holler, J. (2017). Gaze direction signals response preference in conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 50(1), 12–32.

Kidwell, M. (2006). “Calm down!”: The role of gaze in the interactional management of hysteria by the police. Discourse Studies, 8(6), 745-770.

Klein, W., & Miller, M. (1981). Moral argumentation among children. A case study. Linguistische Berichte, 74(81), 1–19.

Koshik, I. (2003). Wh-questions used as challenges. Discourse Studies, 5(1), 51–77.

Koshik, I. (2005). Beyond Rhetorical Questions: Assertive Questions in Everyday Interaction. Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Kotthoff, H. (1993). Disagreement and Concession in Disputes. On the Context Sensitivity of Preference Structures. Language in Society, 22(2), 193–216.

Kreuz, J., & Luginbühl, M. (2020). From flat propositions to deep co-constructed and modalized argumentations: Oral argumentative skills among elementary-school children from grades 2 to 6. Research on Children and Social Interaction, 4, 93–114.

Kyratzis, A., Ross, T. S., & Kroymen, S. B. (2010). Validating justifications in preschool girls' and boys' friendship group talk: Implications for linguistic and socio-cognitive development. Journal of Child Language, 37, 115–144.

Lebrun, C. (1734/1980). A Method to Learn to Design the Passions Proposed in a Conference on the General and Particular Expression, etc. Translat-ed by John Williams. Los Angeles: Augustan Reprint Society, Publication Numbers 200-201.

Li, X. (2021). Multimodal practices for negative assessments as delicate matters: Incomplete syntax, facial expressions, and head movements. Open Linguistics, 7(1), 549–568.

Maynard, D. W. (1986). Offering and soliciting collaboration in multi-party dis-putes among children (and other humans). Human Studies, 9, 261–285.

Mondada, L. (2014). The local constitution of multimodal resources for social Interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 65, 137–156.

Mondada, L. (2015). The facilitator's task of formulating citizens' proposals in political meetings: Orchestrating multiple embodied orientations to recipients. Gesprächsforschung – Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion, 16, 1–62.

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction. Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language Social Interaction, 51, 85–106.

Mundwiler, V., & Kreuz, J. (2018). Collaborative Decision-Making in Argumentative Group Discussions Among Primary School Children. In S. Oswald, T. Herman, & J. Jacquin (Eds.), Argumentation and Language — Linguistic, Cognitive and Discursive Explorations (pp. 263–285). Cham: Spring-er.

Oloff, F. (2020): "Hm? He? Hä? - Some Embodied Features of Open Class Repair Initiation in Spoken German [talk]," in International Workshop "Facial Gestures in Interaction" (Bayreuth, Germany).

Quasthoff, U., Heller, V., & Morek, M. (2017). On the sequential organization and genre-orientation of discourse units in interaction. An analytic framework. Discourse Studies, 19(1), 84–110.

Rossi, G. (2020): Other-repetition in conversation across languages: Bringing prosody into pragmatic typology. Language in Society, 49, 495–520.

Ruusuvuori, J., & Peräkylä, A. (2009). Facial and Verbal Expressions in Assessing Stories and Topics. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 42(4), 377–394.

Sacks, H. (1995). Lectures on Conversation. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Schönfelder, N., & Heller, V. (2019). Embodied reciprocity in conversational argumentation. Soliciting and giving reasons with Palm Up Open Hand gestures. Proceedings of the 6th Gesture and Speech in Interaction GESPIN, 81–86.

Selting, M. (1994). Emphatic speech style – with special focus on the prosodic signaling of heightened emotive involvement in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 22(3), 375–408.

Selting, M. (1995). Prosodie im Gespräch. Aspekte einer interaktionalen Phonologie der Konversation. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.

Selting, M. et al. (2011). A system for transcribing talk-in-interaction: GAT 2. translated and adapted for English by E. Couper-Kuhlen and D. Barth-Weingarten. Gesprächsforschung - Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Inter-aktion, 12, 1–51.

Sidnell, J., & Stivers, T. (2013). The handbook of conversation analysis. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Sidnell, J. (2013). Basic Conversation Analytic Methods. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 77–99). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Spranz-Fogasy, T. (1986). „widersprechen“. Zu Form und Funktion eines Aktivitätstyps in Schlichtungsgesprächen. Eine gesprächsanalytische Untersuchung. Tübingen: Narr.

Steensig, J., & Drew, P. (2008). Introduction: Questioning and affiliation/disaffiliation in interaction. Discourse Studies, 10(1), 5–15.

Stevanovic, M., & Peräkylä, A. (2012). Deontic Authority in Interaction: The Right to Announce, Propose, and Decide. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 45(3), 297–321.

Stevanovic, M. (2012). Establishing joint decisions in a dyad. Discourse Studies, 14(6), 779–803.

Stevanovic, M. (2013). Constructing a proposal as a thought. A way to manage problems in the initiation of joint decision-making in Finnish workplace interaction. Pragmatics, 23(3), 519–544.

Stivers, T. (2002). Participating in decisions about treatment: overt parent pressure for antibiotic medication in pediatric encounters. Social Science & Medicine, 54, 1111–1130.

Stivers, T., Heritage, J., Barnes, R. K., McCabe, R., Thompson, L., & Toerien, M. (2018). Treatment Recommendations as Actions. Health Communication, 33(11), 1335–1344. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2017

Stivers, T., & Sidnell, J. (2016). Proposals for Activity Collaboration. Research on Children in Social Interaction, 49(2), 148–166.

Streeck, J. (2007). Geste und verstreichende Zeit. Innehalten und Bedeutungswandel der „bietenden Hand“. In H. Hausendorf (Eds.), Gespräch als Prozess. Linguistische Aspekte der Zeitlichkeit in verbaler Interaktion (pp. 155–177). Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag.

Streeck, J. (2009). Forward-Gesturing. Discourse Processes 46(2-3), 161–179.

Stukenbrock, A. (2018). Forward-looking. Where do we go with multimodal projections? In A. Deppermann & J. Streeck (Eds.), Time in Embodied Interaction: Synchronicity and Sequentiality of Multimodal Resources (pp. 31–68). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Tainio, L. (2012). Prosodic imitation as a means of receiving and displaying a critical stance in classroom interaction. Text & Talk, 32(4), 547–568.

Tracy, K., & Robles, J. (2009). Questions, questioning, and institutional practices: An introduction. Discourse Studies, 11(2), 131–152.

Waring, H. Z. (2012). Yes-no questions that convey a critical stance in the lan-guage classroom. Language and Education, 26(5), 451–469.

1 GAT follows as many principles and conventions as possible of the Jefferson-style transcription but additionally entails conventions that are relevant for linguistic analyses.↩

2 The focus child's bodily resources are consistently highlighted in red in all transcripts.↩

3 By virtue of the elliptical question format in which the verb and the personal pronoun are missing, it remains open whether it is a negative interrogative such as 'don't you take the matches?' (Heritage, 2002) or a declarative question 'you don't take the matches?' (Koshik, 2005).↩

4 Note that in this interaction a schisming (Egbert, 1993) occurs. While Sila and Damira discuss the knife, Faris and Seyla negotiate the flashlight.↩