Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Speaker Eyebrow Raises in the Transition Space:

Pursuing a Shared Understanding

Rebecca Clift1 & Giovanni Rossi2

1University of Essex

2University of California, Los Angeles

Abstract

In this article, we examine a distinctive multimodal phenomenon: a participant, gazing at a recipient, raising both eyebrows upon the completion of their own turn at talk – that is, in the transition space between turns at talk (Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson, 1974). We find that speakers deploy eyebrow raises in two related but distinct practices. In the first, the eyebrows are raised and held as the speaker presses the recipient to respond to a disaffiliative action (e.g. a challenge); in the second, the eyebrows are raised and quickly released in a so-called eyebrow flash as the speaker invites a response to an affiliative action (e.g. a joke). The former practice is essentially combative, the latter collusive. Although the two practices differ in their durational properties and in the kinds of actions that they serve, they also have something in common: they invoke a shared knowledge or understanding between speaker and recipient.

Keywords: conversation, facial expression, eyebrows, hold, flash, challenge, allusion

1. Introduction

Eyebrow movements are a central component of facial behaviour. Although as interactants we seldom reflect on the importance of the face as a communicative resource, the COVID-19 pandemic put the spotlight on our eyes and eyebrows: the area of our face that is not covered by a mask. But facial behaviour fascinated scholars long before the pandemic, and movements such as eyebrow raising and furrowing have been linked to fundamental aspects of human interaction, from the expression of emotion to the display of attitudes to the accomplishment of social action.

In this study, we examine eyebrow raising in ordinary conversation, focussing on its occurrence in a particular sequential position: the transition space between turns at talk, where speaker change is relevant (Sacks et al., 1974). The eyebrow raises that we focus on are all produced by the speaker of the turn that precedes the transition space (Clayman, 2013) as he or she is gazing at the recipient. We find that speakers can use such eyebrow raises in two ways, in two related but distinct practices. In the first, the eyebrows are raised and held as the speaker presses the recipient to respond to a disaffiliative action (e.g. a challenge); in the second, the eyebrows are raised and quickly released in a so-called flash as the speaker invites a response to an affiliative action (e.g. a joke). Although the two practices differ in their durational properties and in the kinds of actions that they serve, they also have something in common: they invoke a shared knowledge or understanding between speaker and recipient. We conclude by considering what the distinctions in practice and in context tell us about the communicative functions of the eyebrow raise in general. Firstly, however, we situate our study in the context of previous research on eyebrow movement in communicative conduct.

2. Background

Darwin described eyebrow raising as an expression of 'attention', a state that may 'increase into surprise', as reflected in the degree of raising (1872:278). He also described frowning (or the furrowing of the eyebrows) as the expression 'of something difficult or displeasing encountered in a train of thought or in action' (p. 224). Since these writings, the dominant approach to the study of eyebrow movements has been grounded in the view that facial expression is an involuntary manifestation of emotional experience (see Fernández Dols and Russell, 2017, and the introduction to this special issue, for reviews). At the same time, much linguistic research in this area has focused on whether and how eyebrow movements are coordinated with intonation, with the aim of explaining the audiovisual production and perception of words, sentences and discourse structure (e.g. Cavé et al., 1996; Pelachaud, Badler and Steedman, 1996; Swerts and Krahmer, 2010). In the present study, our interest is in how eyebrow raises are used in the accomplishment of distinct social actions in interaction. The following review thus focuses on literature that is relevant to this theme. Along the way, we also discuss research on conversational timing, turn-taking and action sequencing, as these features of conversation are key to understanding our object of study: eyebrow raises produced by speakers in the transition space between turns at talk.

Eyebrow raises have long been associated with questions (Darwin, 1872; Birdwhistell, 1970; Eibl-Ebesfeldt, 1972; Ekman, 1979; Chovil, 1991), and experimental studies have found that speaker eyebrow raises help recipients distinguish questions from statements (Srinivasan and Massaro, 2003; Borràs-Comes et al., 2014). Research based on conversational data, however, puts these findings into perspective, with one study reporting that questions are less frequently accompanied by speaker eyebrow raises than instructions and receipts of new information (Flecha-García, 2010) and another study showing a relatively low co-occurrence (20%) of eyebrow raises with questions (Nota, Trujillo and Holler, 2021). Adding to the complexity of the picture is that, in sign language research, eyebrow raises are considered grammatical markers of polar questions (Coerts, 1992; Baker-Shenk, 1983; Kyle and Woll, 1985; Dachkovsky and Sandler, 2009), a function that interacts with other 'affective' functions of eyebrow movements during questions (de Vos, van der Kooij and Crasborn, 2009).

Besides questions, speaker eyebrow raises have been associated with other types of conversational actions, including greetings (Eibl-Ebesfeldt, 1972; Ekman, 1979; Duranti, 1997), backchannels, news receipts (Chovil, 1991; Dix and Groß, 2023/this issue), as well as with other conversational functions such as topic management and activity transitions (Chovil, 1991; Flecha-García, 2010).

More recent research adopting a conversation-analytic approach has introduced greater control over the sequential placement of eyebrow movements, more specificity in the characterisation of the actions that they accompany, and an analysis of the responses that these actions make relevant. This line of research has found fertile ground, especially in the domain of other-initiated repair (Enfield et al., 2013; Manrique, 2016; Hömke, 2018; Gudmundsen and Svennevig, 2020; Wang and Li, 2023/this issue; Stolle and Pfeiffer, 2023/this issue). Studies in this domain show that speaker eyebrow movements are common in other-initiations of repair, with one study finding a co-occurrence of 40% with eyebrow raises or furrows (Hömke, 2018:76). The same study also shows that raises and furrows are both used across different types of repair initiation including 'open requests' (e.g. Huh? Sorry?), 'restricted requests' (e.g. Who? Forty nine what?) and 'restricted offers' (e.g. You mean the tall guy?) (see Dingemanse and Enfield, 2015 for a definition of these types). At the same time, repair initiations with raises and furrows differ in the types of repair operations they generate: repair initiations with raises are often responded to with confirmation or disconfirmation (57%) and less often with clarification (25%), whereas repair initiations with furrows are more likely to be responded to with clarification (65%), whether or not this is accompanied by other repair operations (Hömke, 2018:81–83). Further, when we consider repair-like sequences initiated by repeating what another interlocutor has just said, eyebrow raises and furrows participate in the distinction between actions that extend beyond initiating repair (Rossi, 2020): raises co-occur with affiliative displays of surprise (see also Dix and Groß, 2023/this issue), whereas furrows co-occur with disaffiliative actions of questioning the acceptability of what has been said. As we will see, however, the relation of eyebrow raises to affiliative versus disaffiliative actions varies depending on the sequential context.

An understanding of eyebrow movements in conversation would not be complete without considering their timing. Like other facial expressions, most eyebrow movements, including raises, occur early relative to the verbal utterance they accompany, before or shortly after its onset (Nota et al., 2021). Eyebrow movements may also precede spoken turns to foreshadow certain kinds of actions or shifts in stance (Peräkylä and Ruusuvuori, 2012; Kaukomaa, Peräkylä and Ruusuvuori, 2013, 2014). Some eyebrow movements, however, are produced late relative to the verbal utterance they accompany (Nota et al., 2021). While we are not aware of any prior research on the actions or functions accomplished by late eyebrow raises in naturally occurring conversation, an experimental study suggests that speaker eyebrow raises produced after an ironic utterance, along with sustained gaze at the recipient, may help the recipient recognise the ironic content (González-Fuente, Escandell-Vidal and Prieto, 2015). As we will see, this pattern is consistent with one of the eyebrow raising practices that emerge in our study.

Just as important as the onset of eyebrow raises relative to the start or end of spoken turns is how long the eyebrows stay raised before being released, that is, their duration. One way of assessing duration is by measuring it in absolute terms, that is, in seconds or milliseconds. For example, Nota et al. (2021) find that eyebrow raises in question-response sequences have a median duration of 640 milliseconds. Although this finding is based on all eyebrow raises produced by both speakers and recipients of questions in a conversational corpus, it suggests a possible baseline for gauging eyebrow raises as being relatively long or short (see also Dix and Groß, 2023/this issue).

Another way of assessing the duration of eyebrow raises is by situating them in conversational structure. More specifically, we can ask whether the raise is held across turns or over the course of a sequence of actions. Prior research shows that visible holds, including the holding of gaze direction, hand gestures, body posture and facial expressions are used to indicate the unresolved or ongoing status of a sequence, with the disengagement of the hold indicating its resolution or completion (Rossano, 2012; Sikveland and Ogden, 2012; Groeber and Pochon-Berger, 2013; Li, 2014; Floyd et al., 2016; Manrique, 2016). In this special issue, Dix and Groß document the use of eyebrow raises in the context of news receipts and newsmarks after the delivery of new, unexpected, and affiliative information. They find that rapid eyebrow raises without a hold are associated with news receipts that project sequence closure, whereas newsmarks displaying surprise or astonishment are accompanied by eyebrow raises that are held to encourage sequence expansion.

While Dix and Groß and other contributors to this special issue examine eyebrow raises as recipient behaviour, in this study we examine them as speaker behaviour. Unlike previous research on 'audiovisual prosody', however, our focus is not on the coordination of eyebrow movements with intonation, but rather on movements that are unaccompanied by talk or minimally overlapping with it, thus not produced for purposes of accentuation. Specifically, we examine eyebrow raises in the transition space between turns at talk, where speaker change is relevant (Sacks et al., 1974; Clayman, 2013). The transition space is a window of opportunity that emerges when a speaker's turn-constructional unit (TCU) is coming to a point of possible completion. The space typically opens when the current speaker is in the process of completing the TCU and extends through the silence that may follow the TCU's completion. As such, the transition space is structurally related to turn endings but can be more broadly conceptualised as a sequential position between turns at talk.

By focussing on speaker eyebrow raises in the transition space, we are not looking at anticipatory uses of facial expression, but rather at how it can retrospectively indicate something about the just-prior talk (González-Fuente et al., 2015). Finally, our analysis adds to previous and current research on the timing and durational properties of visible behaviour, drawing a distinction between uses of the same facial expression with and without a hold (see also Dix and Groß, 2023/this issue).

3. Data and Methods

Our data were drawn from a number of sources. One corpus (from which Extracts 1 and 3 were taken) was footage of a British family filmed continuously in their homes across 100 days by over 20 cameras. This footage was broadcast in edited form on British television, and we have permission from Dragonfly Productions, who filmed it, to use it for academic research. We hope it will be apparent that, despite this footage being edited, the data has not been analytically compromised and the phenomenon of focus is robust. Eight hours of this footage were investigated for this study. Another source was the Rossi Corpus of English (RCE), collected across three urban centres in northern England. Many of these recordings were made on a university campus, including interactions among students and among staff, and involving speakers of both British and American English. Informed consent for scientific use of these recordings was obtained from all participants. Of this corpus, we reviewed 15 recordings of a total of approximately seven and a half hours of footage. A third source was six publicly available news interviews conducted in the United States, which altogether added up to about one hour.

In reviewing these data for instances of our phenomenon, we combined two strategies: i) watching recordings in their entirety and ii) targeted searches aimed at junctures in the interactions where we hoped to find speaker eyebrow raises in the transition space. Our final collection consisted of 19 total instances, eight of which we analysed as eyebrow holds and eleven as eyebrow flashes.

We used ELAN (Wittenburg et al., 2006) to measure the duration of eyebrow raises, using the zoom function to increase visibility and creating annotations on a frame-by-frame basis. Since all video files had a resolution of 25 frames per second, our measurements had a time resolution of approximately 40 milliseconds (the duration of a single frame). We took the first frame where eyebrow movement began as the start of the raise and the last frame before its retraction was complete as the end. In two cases from the British TV corpus, both of which are examined here, only a partial measurement was possible as the camera cut away when the raise was still in progress.

Our multimodal transcripts generally follow Mondada's (2019) conventions.

4. Eyebrow Raises with Hold: Pursuing a Response to a Challenge

In this section, we examine instances where a participant, having come to the end of a TCU and turn, and gazing at a recipient, raises her eyebrows, keeping them momentarily raised in a hold (see Figure 1 below). The eyebrow raise is thus visible as being produced unaccompanied by talk and in the transition space between turns.

In Extract 1, which takes place late at night, Jane is trying to persuade her nineteen-year-old daughter Emily not to go out clubbing (l. 3–9) with an assurance that Jane will stay up (by implication to appreciate Emily's obliging conduct). Her imperative plea, '↑Be a nice daughotero.' is initially met by a two-second silence, whereupon Emily responds with 'I am a nice ↓daughte:r.' (l. 18). This response is, in turn, met by one second of silence, whereupon Emily, fixing her gaze on Jane, raises her eyebrows and keeps them raised for over 2.3 seconds (l. 21–27).

Extract 1. Clift_Family_1 'I am a nice daughter'

Open in a separate window

The raise of the eyebrows is produced in an environment where the participants are evidently at odds. Jane is trying to persuade Emily to abandon a course of action, which Emily is clearly resisting. Jane's subsequent change of tack, appealing to Emily's self-image, '↑Be a nice daughotero.' (l. 14), is met by Emily's delayed response, 'I am a nice ↓daughte:r.'. Like the 'do-construction' (Raymond, 2017), which indexes a contrast with a prior understanding, the stress on the auxiliary verb here works to contrast with and undermine the presupposition conveyed in the prior turn, namely that she is currently not 'a nice daughter'. The assessment here plays on the stereotypical assumption that a 'nice daughter' is one who stays at home rather than going out – and, furthermore, complies with her mother's expressed wishes. 'I am a nice ↓daughte:r.' thus works to disengage this assumption from the assessment as applied to her.

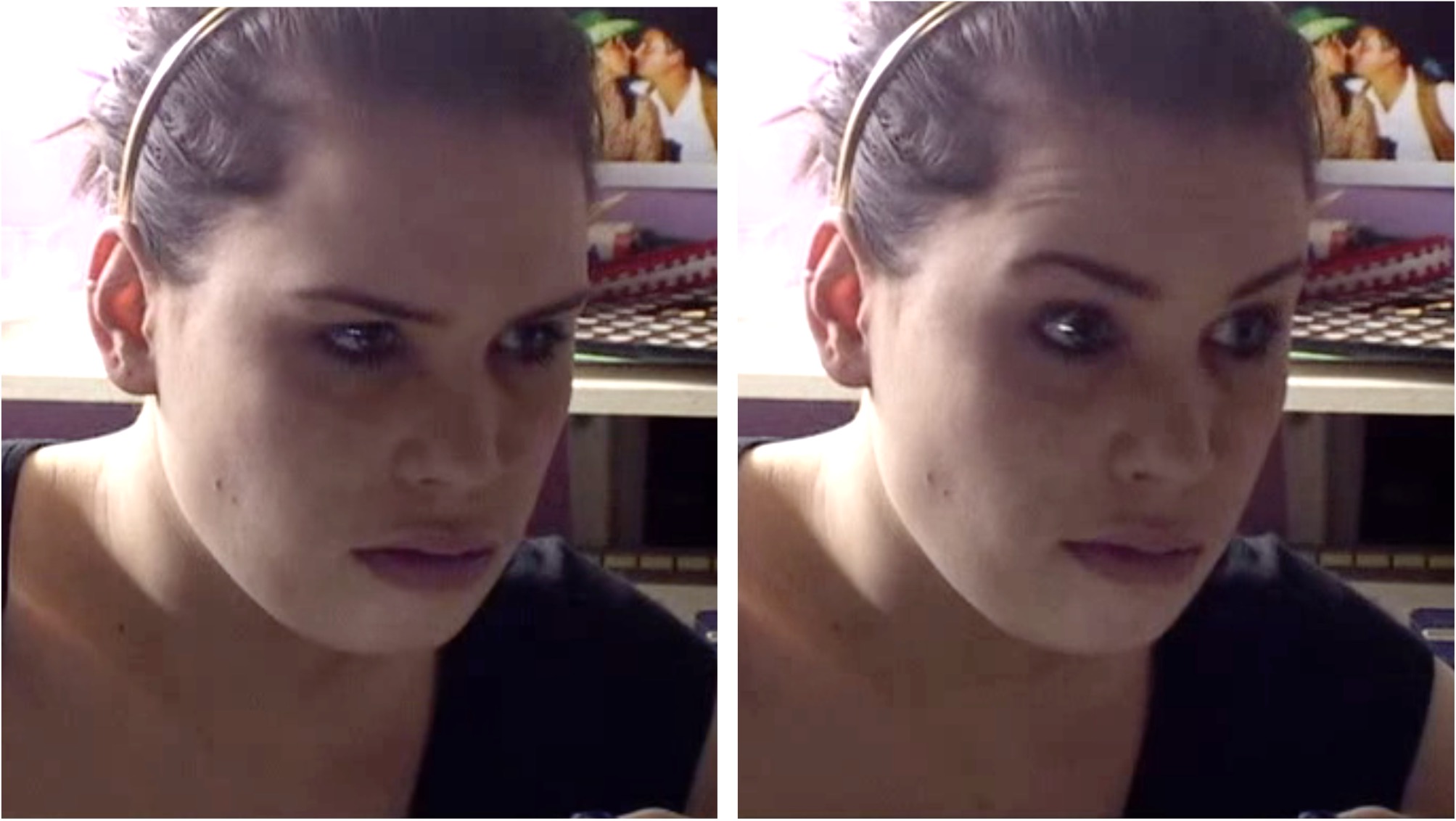

Figure 1. Frames from Extract 1. In (a), Emily is gazing at Jane during the silence that follows her turn 'I am a nice daughter' (l. 23). In (b), later during the same silence, Emily is raising her eyebrows and holding them in raise (l. 25).

The multimodal design of 'I am a nice ↓daughte:r.' includes the speaker's steady gaze at the recipient, a response-mobilising feature (Stivers and Rossano, 2010). In addition, the TCU is an assertion that – as a positive self-assessment – strongly projects a response in its preference for agreement, not least because the recipient is the mother of the speaker. As such, 'I am a nice ↓daughte:r.' is hearable as a challenge. And yet, as is evident from the silence in its wake, Jane resists agreeing with an assertion that would directly undermine the grounds for her earlier injunction to '↑Be a nice daughotero.' (l. 14). It is during the silence of Jane's resistance – 0.6 seconds after Emily has finished her turn – that she produces the eyebrow raise and hold. This gap between the end of the verbal turn and the mobilisation of the eyebrow raise plus hold in a context where the speaker's gaze is already on the recipient underscores the response-pursuing function of the practice (see also Rossano, 2012: Chapter 3, on contexts where a speaker's gaze shifts from looking away or down to looking at the recipient when a response is not forthcoming). This practice can thus be seen as pursuing a response in an environment where the required response has been made plain: in effect, mandating a response, such that its absence is hearable. In this case, more than two seconds of silence pass before Emily herself verbalises, with an imperative, what she is pursuing from Jane: 'Agree.'. Here, the verbal pursuit achieves its aim, albeit weakly. Jane – after a further two seconds of resistance – concedes, albeit minimally and under her breath ('ooOkay then.oo,' l. 30).

A second case shows the same practice mobilised in a similar, albeit less combative, environment of disaffiliation. In Extract 2, Andy, Ben, and Charlie are talking about the British television programme Question Time, in which a political panel, mediated by a chair, takes questions from the studio audience. A recent episode ('That Question Time', l. 1) featured the far-right British National Party leader, Nick Griffin. Andy produces an assessment of it ('shi::t') to which Ben responds, not with the preferred response (an agreement) but with the caveat (l. 5–7) that it was 'set up', by implication rendering the assessment invalid. Andy confirms Ben's assertion by echoing it but reiterates his assessment (l. 8). At this point, Charlie, overlapping Ben's attempt to expand on his assertion about the programme being a fix, states that it 'was always ↑going to be.' (l. 11), upgrading the knowingness already displayed by Ben into a display of absolute epistemic certainty, underscored by the extreme-case formulation (Pomerantz, 1986) and the pitch peak on '↑going'. As Charlie produces this TCU, he extends his left arm outwards in what is recognisable as a one-armed variant on the challenging 'palm-up' gesture in a hold (Clift, 2020) (see Figures 2 and 3a). He then appends to that first TCU a subsequent question: 'What were you expecting.' (l. 11–17), dropping his extended left arm back with a slap of the hand to his left thigh on the second syllable of 'expecting.' (Figure 3b). It is at the end of this question that Charlie raises his eyebrows (l. 20).

Extract 2. RCE07_522696 'What were you expecting?'

Open in a separate window

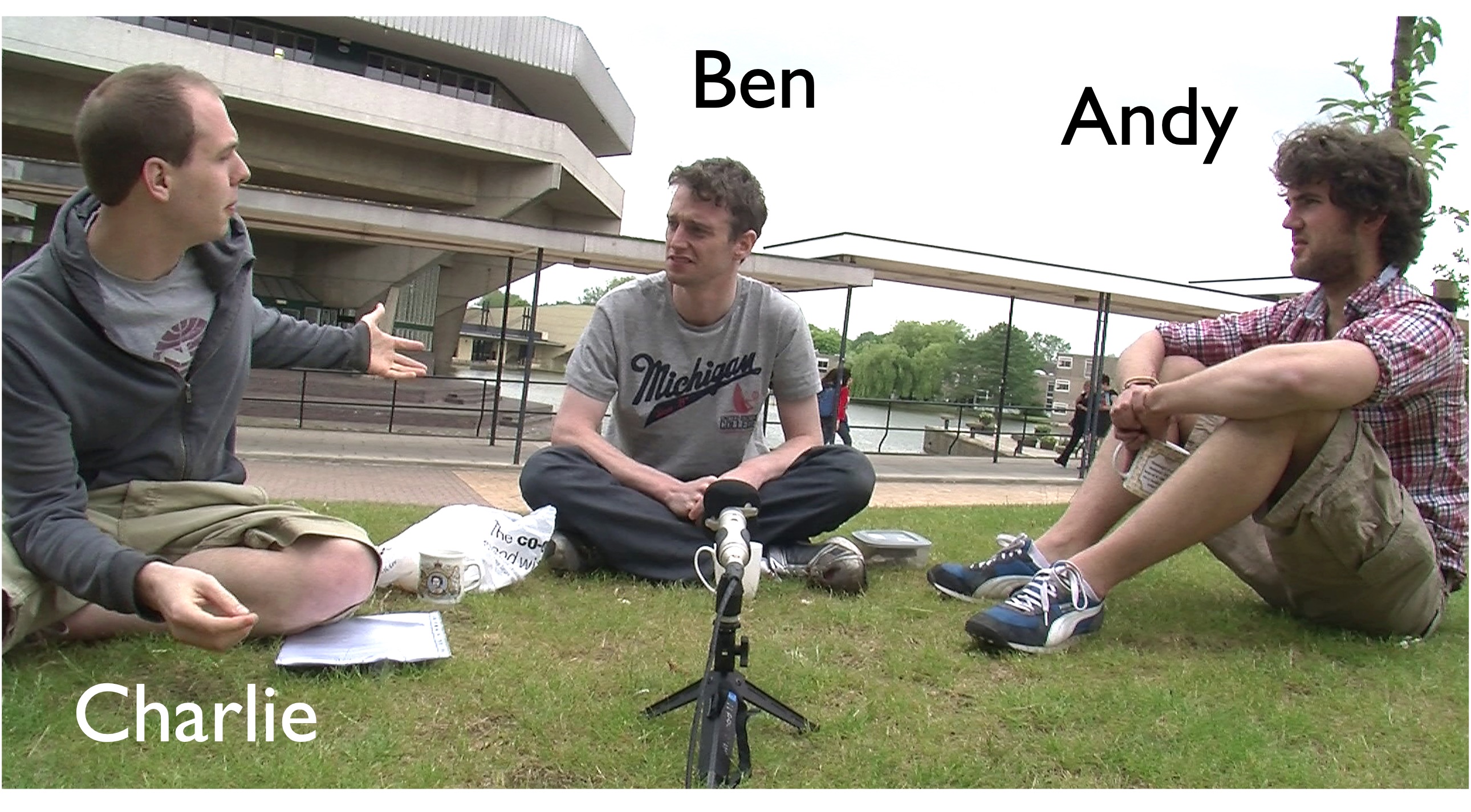

Figure 2. Frame from Extract 2, showing the spatial arrangement of the three participants and Charlie's palm-up gesture as he says '↑going to be.' (l. 11).

Figure 3. Frames from Extract 2. In (a), Charlie is saying '↑going to be.', gazing at Ben and making a palm-up gesture (l. 16). In (b), he is saying 'expecting.', with the palm-up gesture now fully retracted (l. 19). In (c), he is raising his eyebrows and holding them in raise in the transition space (l. 22).

Charlie's eyebrow raise, beginning at the end of his turn, 'What were you expecting.' (l. 20) – detectable in Figure 3c also by dint of a horizontal wrinkle over the eyebrow – is produced in a comparable sequential context to Emily's in Extract 1: following a challenge (see also Heritage, 2012 on so-called 'rhetorical questions' in the How can/could you format and how they are framed as unanswerable).1

Both instances of eyebrow raising in Extracts 1 and 2, then, are produced immediately after challenges in disaffiliative environments – the former highly confrontational, the latter less so, but still discordant. In such contexts, they constitute pursuits to responses that are yet to be produced. In both cases, the recipients respond in a dispreferred manner: in Extract 1, Jane declines to respond and only does so, weakly, when Emily produces a further, imperatively-formatted verbal pursuit ('Agree.'); in Extract 2, Ben meets Charlie's questioning challenge and eyebrow raise with a turn launched by the counter-positional 'W'l no,' (l. 23).

A third instance illustrates the generic features of this practice. The participants are Emily and her mother Jane, who featured in Extract 1. In common with Extracts 1 and 2, the eyebrow raise in Extract 3 is again produced in a disaffiliative environment. Here, Emily, who works in a shop run by a woman called Pauline, has been summoned by her father, Simon, to the dining room to talk to her mother. Despite Emily asking Simon why she has been summoned, he has resisted telling her. The extract starts as Emily enters the dining room where Jane is seated.

Extract 3. Clift_Family_1 'Because you're in the wrong?'

Open in a separate window

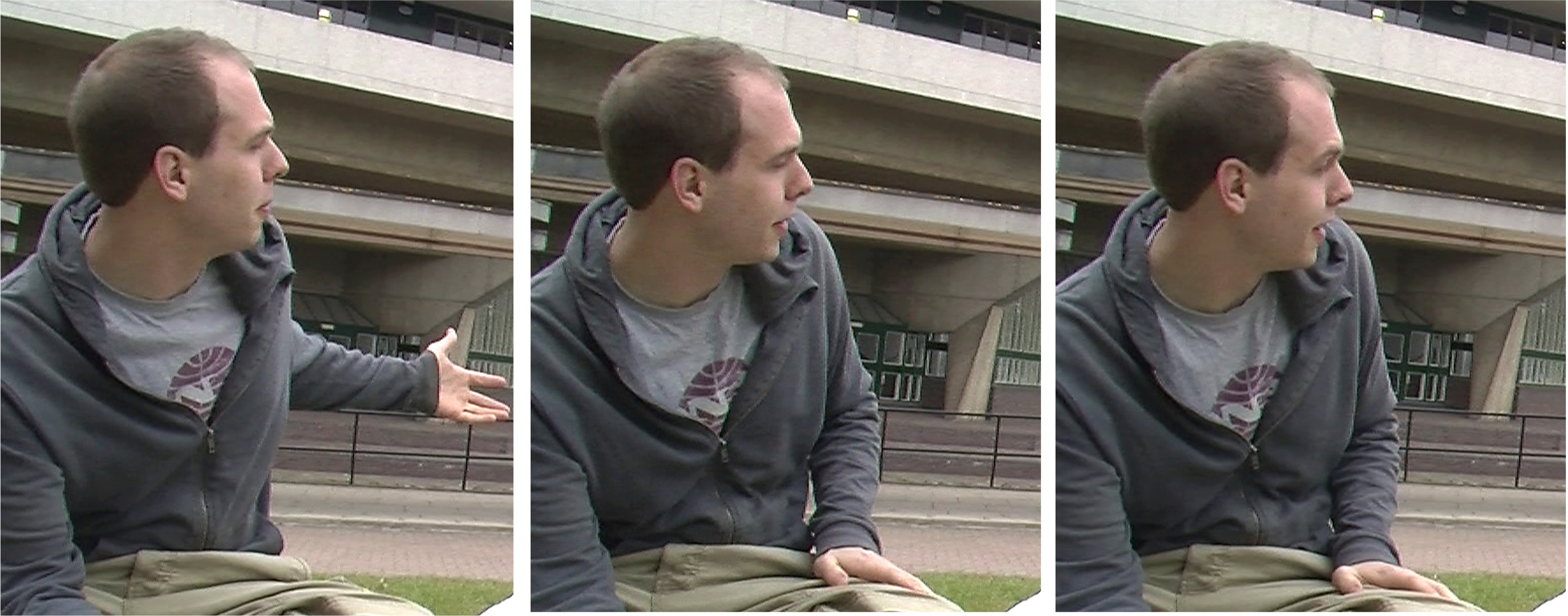

The summoning of Emily, Jane's launch of a recognisable story (l. 1), and her subsequent directive, 'Sit down.' (l. 3), avoiding Emily's gaze, all adumbrate some form of admonishment for Emily. As Jane reports to Emily the 'little ↑chat' (l. 8) she had with Emily's boss '<Abou:t the fact that you're always ill>.' (l. 10), Emily, clearly recognising this extreme-case formulation as a complainable and thus an implicit accusation, turns away from Jane (l. 12) and gets up to go (l. 15), which Jane intercepts with multiple 'no's' (l. 16) (Stivers, 2004). However, Emily proceeds with her course of action, whereupon Jane asks a question glossing Emily's behaviour: 'Why you getting all defensive.' (l. 19), then immediately appending to this a TCU that is syntactically formed as a candidate answer, but which is prosodically formed as another question: 'Because you're in the ↑wrong?' (l. 23). Figure 4a shows Jane as she produces the word '↑wrong?'. Immediately on the completion of the turn, Jane raises her eyebrows (Figure 4b), keeping them held.

Figure 4. Frames from Extract 3. In (a), Jane is in the middle of saying '↑wrong?', gazing at her daughter Emily (l. 25). In (b), during the silence that follows, Jane is raising her eyebrows and holding them in raise (l. 28).

Jane thus raises her eyebrows at the point at which she has just asked a question with her own candidate answer – an answer, moreover, that is hearable as an explicit accusation in assessing Emily as having committed wrongdoing. Epistemic status here trumps prosodic form (Heritage, 2012), so that while the eyebrow raise is seen to pursue a response from Emily, it is a response which Jane has all too clearly just voiced herself. Jane's apparent question thus resembles what Koshik (2005) calls assertive questions, which, far from seeking information, seek to challenge, implying the opposite of what they are asking. Here, 'Because you're in the ↑wrong?' clearly implies its corresponding assertion: 'because you're in the wrong!'. The eyebrow raise is thus produced in an environment in which the nature of the response being pursued has been made already clear by its producer. This appeal to what is already known by both speaker and recipient can be compared to the effect of Charlie's unanswerable question 'What were you expecting.' in Extract 2 and of Emily's hard-to-refute assertion 'I am a nice ↓daughte:r.' in Extract 1.

In these three cases, we thus see that a speaker raises their eyebrows and holds them in a raise in the transition space after producing a challenge or an otherwise disaffiliative action. By looking at the recipient and raising the eyebrows with a hold, the speaker pursues a response, the nature of which has been made all too clear. As such, this practice stands in contrast with other ways of pursuing response where the speaker elaborates on or repairs their prior talk, ostensibly addressing a problem of understanding (e.g. Bolden, Mandelbaum and Wilkinson, 2012). In our cases, the speaker clearly does not treat the problem as one of understanding but rather as one of disagreement and/or disaffiliation.

As for the timing of the eyebrow raise, the movement can begin at the end of the speaker's turn (Extracts 2 and 3) or after a silence (Extract 1). The raise lasts 620 milliseconds in Extract 2, at least 720 milliseconds in Extract 3, and at least 2300 milliseconds in Extract 1.2 It is possible to speculate that the longer duration of the hold in Extract 1, and possibly in Extract 3, correlates with a more vigorous pursuit of a response in what is a more disaffiliative and confrontational environment. That said, in all cases the hold of the raised eyebrows pursues a response that is due and iconically embodies the unresolved nature of the sequence at that point, a finding which underscores previous work on bodily holds (see Background). It is therefore an essentially combative practice.

5. Eyebrow Flashes: Signalling an Allusion

In this section, we examine a related but distinct practice of raising the eyebrows in the transition space. Unlike eyebrow raises with a hold, flashes are relatively quick movements where the eyebrows are raised and released without being visibly kept in position. The rapid realisation of the gesture, as we will see, makes possible its repetition, with two or three flashes produced in quick succession. Typically, however, these eyebrow flashes are single gestures. We will also see that these movements can be accompanied by other nonverbal features in the service of the same action (e.g. hand and head gestures, smiling, clicks).

The goal of this section is two-fold: i) to illustrate how eyebrow flashes work as a distinctive communicative practice for speakers in the transition space and ii) to shed light on the kinds of actions that eyebrow flashes contribute to producing and how these differ from those examined in the previous section.

In Extract 4, Roger has stopped by a university cafeteria table where his friend Max is sitting with two other students, Jamie and Will (see Figure 5). Roger and Max are both acting in a play titled Art which, as Max previously described, 'is about three friends' who fall out over the purchase of an expensive painting. We join the interaction as Roger asks Jamie and Will if they are going to see the play that weekend (l. 1), to which Jamie responds affirmatively (l. 2), adding that, since he has seen the play before, he is going to be 'critically judging. […] Everything:.' (l. 8, 11). A moment later, Will elaborates on Jamie's quip by parodying Jamie writing down critical notes on his notepad (l. 14), generating laughs from Max and Jamie (l. 16–17). Meanwhile, Roger has begun telling a joke based on the play's theme. After an initial attempt to launch the joke is overlapped by Will (l. 12–14), Roger goes on to tell the joke in the clear (l. 19–21).

In the joke, Roger announces that there is 'a different version' of the play coming up, a version that is 'about three guys who break wind?'. The implicit punchline draws a parallel between a play about three friends called Art and a play about three guys who break wind called, as Max later articulates (l. 29), 'F:A:::RT_'. Our focus is on how Roger delivers the joke and invites his recipients to infer the punchline.

Extract 4. RCE15b_948085 'Three guys who break wind'

Open in a separate window

Roger delivers the joke while looking at Jamie and Max, maintaining a straight face through the focal line: 'it's about three guys who break wind?' (l. 21–22, Figure 5). The eyebrow flash begins in the transition space (l. 28), just as Jamie and Will are beginning to laugh a little, with Roger now looking specifically at Max, his fellow actor. Roger's focus on Max is further indicated by a pointing gesture toward him that accompanies the eyebrow flash (l. 27, 30, Figure 6a). At this point, Max launches into a full uptake of the joke by articulating the implicit punchline: 'it's called F:A:::RT_' (l. 29), turning around to Jamie (l. 34, Figure 6b) and instigating a choral and now unequivocal appreciation of the joke by all three recipients (l. 38–40).

Figure 5. Frame from Extract 4, line 22. Roger stands by the table where Max, Jamie, and Will are seated as he delivers the focal line of his joke ('it's about three guys who break wind?').

Figure 6. Frames from Extract 4. In (a), Roger's eyebrows are raised as he looks and points toward Max (l. 33). In (b), Roger walks off as Max says 'F:A:::RT_' while looking at Jamie (l. 35).

At first glance, it seems that the function of Roger's eyebrow flash – along with his gaze and pointing gesture – is to pursue a response from Max after the half-second silence that follows the joke. Note, however, that the eyebrow flash begins after Roger has already begun to step away from the table (l. 24) and ends before Max demonstrates full understanding of the joke by saying the word 'fart' (l. 29, 32). Along with its short duration of only 280 milliseconds, the timing of the eyebrow flash suggests that, although it does invite a response, it does not mandate it; in other words, the practice is not designed to sustain conditional relevance (Floyd et al., 2016). Appreciation of the joke is not being vigorously pursued here in the way that a response in Extracts 1 to 3 is. In fact, not only does the eyebrow movement end before the critical word 'fart', so do other nonverbal behaviours that accompany it, including the speaker's pointing gesture (l. 30), gaze, and postural orientation to the recipient (l. 31). Note, finally, that Roger ratifies Max's uptake of the joke while walking away ('A:h,' l. 37), another sign that his earlier eyebrow flash was not tied to sequence closure.

With respect to the nature of the action that the speaker's eyebrow raise serves here, it is antithetical to the disaffiliative actions seen in the previous section: it is a joke that seeks affiliation. It is also a particular kind of joke, one with an implicit punchline to be inferred by the recipient – a quintessentially allusive action. The eyebrow flash contributes to signalling the allusion by inviting the recipient to make the inference based on shared knowledge. In Extract 4, of the three recipients of his joke, Roger specifically gazes at Max, his fellow actor in the play and thus the most knowing recipient.

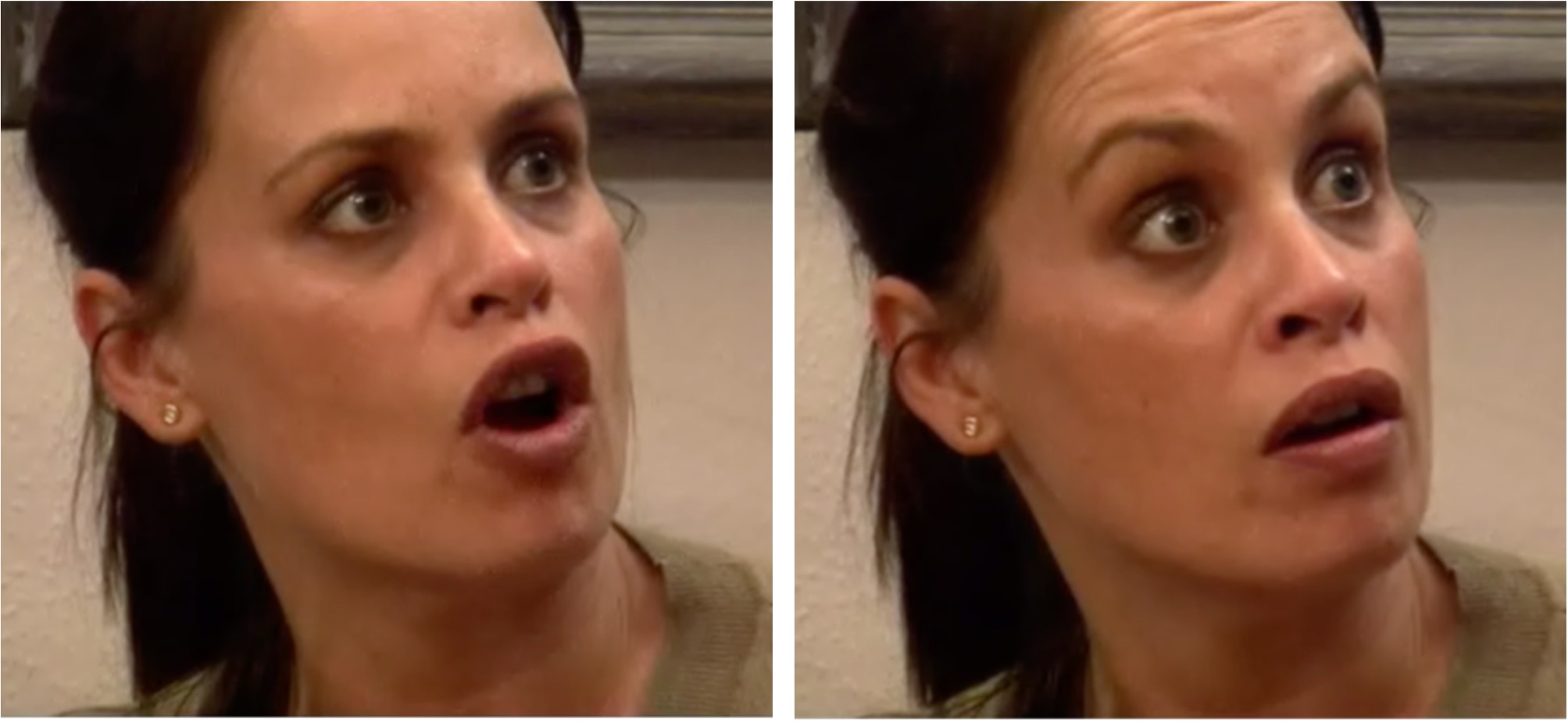

Consider another case involving an allusive assessment. Heather and Kelly are sitting outside, talking about their academic standing as the year comes to an end. Heather is encouraging Kelly to think positively about what she has accomplished: 'I think you'll do quite we:ll, Beca::use_ you've_ put the effort into your research, so_' (l. 3–4, 7), to which Kelly offers only minimal uptake (l. 9, 11). Heather then continues to reassure Kelly with a positive assessment of her research participants: 'And you have the ↑best participants,', using an extreme-case formulation (Pomerantz, 1986) that makes the turn come off as overbuilt. Her facial expression remains neutral, gaze down, through most of the assessment (Figure 7a), until about halfway through the last word 'participants,'. At this point, Heather begins to smile, raises her eyebrows, and gazes up to Kelly (l. 14–16), in an allusion to the fact that she is one of Kelly's participants.

Extract 5. RCE28_1288820 'Best participants'

Open in a separate window

Figure 7. Frames from Extract 5. In (a), Heather's facial expression is still neutral, her gaze down (l. 13). In (b), she is smiling, gazing at Kelly, and her eyebrows are raised as she produces a first lateral click (l. 19). In (c), Kelly is smiling and her eyebrows are raised as she says '£Hooray:::_£' (l. 24).

In this case, the speaker's eyebrow flash is repeated three times in quick succession, each instance lasting between 280–320 milliseconds. The first iteration is produced at the very end of the focal turn (l. 15). The second and third iterations are aligned with the two lateral clicks that follow the end of the verbal turn (l. 17–18, Figure 7b). Post-positioned lateral clicks have been shown to be used after turns that convey 'some element of implicit self-praise and/or an impropriety', where they invite an 'affiliative "knowing" response from the recipient, which includes an appreciation of the action' (Ogden, 2020:83). Heather's lateral clicks here are further evidence of the allusive nature of her reference to Kelly's research participants. Heather's eyebrow flashes are closely coordinated with this vocal gesture, but their contribution to signalling the allusion is arguably independent: the first flash is produced before any click (l. 15) and the recipient's uptake of the allusive action begins in overlap with the first click (l. 17, 20).

What is especially notable about this case is that the eyebrow flashes and the lateral clicks are reciprocated in the recipient's uptake (Ogden, 2020:85). Moreover, the multimodal design of the reciprocation mirrors that of the initiating action. As Kelly says '£Hooray:::_£', she smiles and flashes her eyebrows (l. 20–21, Figure 7c). The eyebrow flash is then repeated as she goes on to produce a lateral click, followed by a '£Yeah,' (l. 20–21). Kelly's response underscores a shared understanding of Heather's allusion, expresses appreciation of it, and displays strong affiliation between them. A moment later, as Heather gazes back down to her phone (l. 23), the interaction shifts back to an earlier topic (l. 27).

Consider now another case involving Heather and Kelly where the allusion carried by the speaker's action is not picked up by the recipient but is revealed in how the speaker follows up on it. Kelly is talking about her brother, an athletic type who often cycles long distances for charity. The prior conversation has revealed that Heather knows Kelly's brother and that she too has an athletic brother who enjoys sports challenges.

When the extract begins, Kelly is explaining what kind of charity her brother will be cycling for next: 'It's not for one specific thing:. So: it'll help. […] Like little ho- like homes in Africa and stuff.But no:t_ (0.3) one:_ (0.7) thing.' (l. 1, 4–5). Plausibly touched off by the mention of Africa, Kelly then goes on to announce that her brother 'wants to climb: Kilimanjaro,' (l. 8–9). The announcement is accompanied by an eyebrow flash that begins around the last syllable of 'Kilimanjaro,' (l. 11) and co-occurs with a head tilt (l. 12, 16) and a slight smile (Figure 8b), indicating that what she has said is not straightforward (see González-Fuente et al., 2015). These movements continue into the following silence (l. 14–16), with the eyebrow raise lasting a total of 280 milliseconds.

Extract 6. RCE28_942449 'Kilimanjaro'

Open in a separate window

Figure 8. Frames from Extract 6. In (a), Kelly is saying 'Kilimanjaro' with no visible eyebrow or head movement or smile (l. 13). In (b), Kelly has just finished saying 'Kilimanjaro' and now has her eyebrows raised, the head tilted, and a slight smile (l. 17). In (c), Kelly continues to look at Heather after lowering her eyebrows, as her head is moving back to home position (l. 18).

Kelly's announcement is followed by one second of silence (l. 14). Although part of the silence is taken up by Kelly's visible behaviour (eyebrow raise, head tilt, smile), it is nonetheless noticeably long and, as it turns out, a harbinger of trouble. When Heather finally speaks, she treats Kelly's announcement as a boast, by giving a competitive response ('Brother's already done it_', l. 19). By pointing out that her own brother has already climbed Kilimanjaro, Heather diminishes rather than celebrates Kelly's brother's plan. In addition, her informing presumes that Kelly did not know or remember that Heather's brother has already achieved the same feat.

What Kelly does next, however, suggests that her announcement was not designed to boast but rather to affiliate, and that Heather's response did not pick up on Kelly's allusion. By saying 'Exactly:,' (l. 20), Kelly not only claims prior knowledge of Heather's brother's achievement but also that the achievement is in fact part of what she was alluding to. Note also the dysfluency ('Can- they can…', l. 23) when she goes on to propose that the two brothers 'exchange tips.' about climbing Kilimanjaro, another indication of the trouble that she is having to repair. Kelly's continuation (l. 23–34) strongly suggests that her earlier announcement was designed to hint at the common interest of their two brothers, and for the two sisters to affiliate rather than compete over it. Note, finally, that while saying 'Exactly:,', Kelly raises her eyebrows again, echoing her earlier eyebrow flash.

In sum, in this case the recipient of an eyebrow flash does not pick up on the allusion carried by the speaker's action. Instead of capitalising on Kelly's hint that their brothers have something in common, Heather's response pits them against each other. What Kelly does in third position, however, sheds light on what her announcement and accompanying eyebrow flash were designed to achieve.

To appreciate an allusion, the recipient has to draw on prior knowledge that speaker and recipient share. In Extract 4, it is knowing that Art – the play that Roger and Max are acting in – is about three friends, which Roger's 'three guys who break wind?' parallels, hinting at but not saying the word 'fart'. The eyebrow flash underscores that there is something not straightforward about what Roger has just said and invites Max to make the inference based on their shared knowledge. In the same way, in Extract 5, the assessment 'And you have the ↑best participants,', with its extreme case formulation, is, on the face of it, a compliment building on a prior positive assessment ('I think you'll do quite we:ll, Beca::use_ you've_ put the effort into your research, so_'). It is only by drawing on their shared knowledge, indexed by the speaker's eyebrow flashes, that the recipient can understand that the speaker herself was one of her participants, thus adding self-praise to the compliment. Finally, in Extract 6, Kelly's report that her brother 'wants to climb: Kilimanjaro,' is, on the face of it, a boast on her brother's behalf, but the eyebrow flash in its wake signals once again that the recipient should not take this at face value and look beyond it for an allusion to Heather's brother's earlier achievement.

All the TCUs that precede the eyebrow flashes subvert the sequences in which they are produced from serious to humorous or whimsical, the first by introducing a set-piece joke, the second by adding knowing self-praise to a compliment (playing on norms against self-praise), and the third by turning an apparent boast into an opportunity to affiliate. The eyebrow flashes serve to indicate that what the speaker has just said is more than what it seems, signalling its allusive nature. The allusiveness plays on norms of delicacy or propriety: the indelicacy of saying the word 'fart' (Extract 4), the impropriety of self-praise (Extract 5), and the apparent brazenness of a boast on another's behalf (Extract 6). In their delicacy they are collusive.

6. Conclusion

The conversation-analytic literature on eyebrow raises typically starts by identifying the particular actions with which such raises are associated. While identifying the social actions implemented by eyebrow raises was a central aim of this study, its analytic starting point was not the actions as such, but rather a sequential position: the transition space. By examining eyebrow raises produced by the speaker of a turn at talk in the transition space between that turn and the next, we have been able to identify both the actions they implement and the interactional environments they inhabit. We have shown that, in this position, the eyebrow raise can take two compositional forms in terms of duration and implementation. These constitute two related but distinct practices, which are deployed in different interactional contexts.

The first practice is the eyebrow raise with a hold, where the eyebrows are kept visibly raised for some moments (in the cases examined here, between 620 and over 2300 milliseconds). This practice is used in broadly disaffiliative environments where the participants are at odds, sometimes strongly, as in Extracts 1 and 3, at other times weakly, as in Extract 2. The TCU that precedes the eyebrow raise projects a particular response (e.g. a backdown or concession), the nature of which has been made clear. Whether the TCU is grammatically constructed as a question (e.g. 'What were you expecting') or an assertion (e.g. 'I am a nice daughter'), it is hearable as a challenge. The eyebrows are raised and held in the wake of this challenge, visibly mandating a response – sometimes after it has become evident that a response will not be immediately forthcoming. The fact that the lack of response is met by a raising and holding of the eyebrows (rather than elaboration or repair, for example) is evidence that the speaker does not take understanding to be at issue, underscoring instead the challenging nature of the practice.

The second practice involves the rapid raising and lowering of the eyebrows in a so-called 'flash' (in the cases examined here, lasting about 300 milliseconds), sometimes more than once. This practice is produced in environments that are broadly affiliative. In contrast to the generally prospective, forward-looking nature of the eyebrow hold, the eyebrow flash is primarily retrospective. An eyebrow flash in the transition space indicates that there is something not straightforward about what has just been said, signalling an allusion. The flash may be accompanied by other embodied practices that contribute to the action being done, such as the hand gesture toward the recipient while moving away from the scene in Extract 4, the lateral clicks in Extract 5, or the slight smile in Extract 6. The allusiveness in each case is grounded in norms of delicacy and propriety. In pointing to prior common knowledge on which the recipient is thereby prompted to draw, the eyebrow flash is subversive, transforming what has hitherto been serious talk into something humorous or whimsical. The eyebrow flash in this position therefore indicates that what has just been said should not be taken at face value. In two of these cases examined here, Extracts 4 and 5, the allusions are immediately understood and appreciated, generating affiliation between speaker and recipient. In Extract 6, the fact that the allusion is not grasped by the recipient results in the speaker undertaking repair work.

Formally, the two practices differ in duration, both absolute and relative. In terms of absolute duration, eyebrow flashes last about 300 milliseconds, while eyebrow holds are at least twice as long (600 milliseconds or more), and sometimes much longer (over two seconds). These findings are broadly consistent with those of Dix and Gross (2023/this issue), who examine recipient eyebrow raises that accompany news receipts and newsmarks. In this context, Dix and Gross find that eyebrow flashes have a duration of between 300 and 700 milliseconds, while eyebrow holds can last from 600 to over 2000 milliseconds.

A reason for greater variability in the duration of eyebrow holds is that their timing is best understood not in absolute terms but, rather, relative to the sequential development of the interaction. Like visible bodily holds found in other environments (e.g. question-answer sequences or other-initiated repair), speaker eyebrow holds in the transition space iconically embody the unresolved or ongoing status of a sequence at that point. As such, their duration is contingent on the resolution of the sequence, which means that the hold may end up lasting longer, as in Extracts 1, or shorter, as in Extract 2, depending on when and whether a response is given. This dovetails with our suggestion that the duration of the eyebrow raise in hold correlates with the intensity of the challenge that it follows. Standing in contrast with this is the brevity of the eyebrow flash, embodying the allusive nature of that which it indexes.

Both practices of eyebrow raising convey a knowingness on the part of the speaker that either mandates, in disaffiliative contexts, or invites, in affiliative contexts, the recipient to respond. So while the eyebrow raise plus hold is an essentially combative practice, the eyebrow flash is essentially collusive. Taken together, these two practices of raising the eyebrows in the transition space show that, in this sequential position, this facial expression is used, at its most generic, to invoke shared knowledge between the speaker and recipient: knowledge that the recipient needs to draw on in responding appropriately.

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to Alexandra Groß, Carolin Dix, and two anonymous reviewers, for comments on our original draft which helped us strengthen and sharpen the argument. We also benefitted from the feedback we received from the audience at the 2023 International Conference on Conversation Analysis (ICCA). Any shortcomings are ours alone.

References

Baker-Shenk, Charlotte L. 1983. "A Microanalysis of the Nonmanual Components of Questions in American Sign Language." Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

Birdwhistell, Ray L. 1970. Kinesics and Context: Essays on Body Motion Communication. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bolden, Galina B., Jenny Mandelbaum, and Sue Wilkinson. 2012. "Pursuing a Response by Repairing an Indexical Reference." Research on Language & Social Interaction 45(2):137–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.673380

Borràs-Comes, Joan, Constantijn Kaland, Pilar Prieto, and Marc Swerts. 2014. "Audiovisual Correlates of Interrogativity: A Comparative Analysis of Catalan and Dutch." Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 38(1):53–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-013-0162-0

Cavé, Christian, Isabelle Guaïtella, Roxane Bertrand, Serge Santi, Françoise Harlay, and Robert Espesser. 1996. "About the Relationship between Eyebrow Movements and Fo Variations." Pp. 2175–78 in Proceeding of 4th International Conference on Spoken Language Processing. Vol. 4.

Chovil, Nicole. 1991. "Discourse‐oriented Facial Displays in Conversation." Research on Language and Social Interaction 25(1–4):163–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351819109389361

Clayman, Steven E. 2013. "Turn-Constructional Units and the Transition-Relevance Place." Pp. 150–66 in Handbook of Conversation Analysis, edited by J. Sidnell and T. Stivers. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Clift, Rebecca. 2020. "Stability and Visibility in Embodiment: The 'Palm Up' in Interaction." Journal of Pragmatics 169:190–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.09.005

Coerts, Jane. 1992. "Nonmanual Grammatical Markers: An Analysis of Interrogatives, Negations and Topicalisations in Sign Language of the Netherlands." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Amsterdam.

Dachkovsky, Svetlana, and Wendy Sandler. 2009. "Visual Intonation in the Prosody of a Sign Language." Language and Speech 52(2–3):287–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0023830909103175

Darwin, Charles. 1872. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. London: J. Murray.

Dingemanse, Mark, and N. J. Enfield. 2015. "Other-Initiated Repair across Languages: Towards a Typology of Conversational Structures." Open Linguistics 1:96–118. https://doi.org/10.2478/opli-2014-0007

Dix, Carolin, and Alexandra Groß. 2023/this issue. "Surprise about or Just Registering New Information? Moving and Holding Both Eyebrows as Visual Change-of-State Markers." Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality 6(3).

Duranti, Alessandro. 1997. Linguistic Anthropology. Cambridge University Press.

Eibl-Ebesfeldt, Irenäus. 1972. "Similarities and Differences between Cultures in Expressive Movements." Pp. 297–311 in Non-verbal communication, edited by R. A. Hinde. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ekman, Paul. 1979. "About Brows: Emotional and Conversational Signals." Pp. 169–202 in Human ethology: Claims and limits of a new discipline, edited by M. von Cranach, K. Foppa, W. Lepenies, and D. Ploog. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Enfield, N. J., Mark Dingemanse, Julija Baranova, Joe Blythe, Penelope Brown, Tyko Dirksmeyer, Paul Drew, Simeon Floyd, Sonja Gipper, Rósa S. Gísladóttir, Gertie Hoymann, Kobin H. Kendrick, Stephen C. Levinson, Lilla Magyari, Elizabeth Manrique, Giovanni Rossi, Lila San Roque, and Francisco Torreira. 2013. "Huh? What? – A First Survey in Twenty-One Languages." Pp. 343–80 in Conversational repair and human understanding, edited by M. Hayashi, G. Raymond, and J. Sidnell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fernández Dols, José Miguel, and James A. Russell, eds. 2017. The Science of Facial Expression. New York: Oxford University Press.

Flecha-García, María L. 2010. "Eyebrow Raises in Dialogue and Their Relation to Discourse Structure, Utterance Function and Pitch Accents in English." Speech Communication 52(6):542–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2009.12.003

Floyd, Simeon, Elizabeth Manrique, Giovanni Rossi, and Francisco Torreira. 2016. "Timing of Visual Bodily Behavior in Repair Sequences: Evidence From Three Languages." Discourse Processes 53(3):175–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2014.992680

González-Fuente, Santiago, Victoria Escandell-Vidal, and Pilar Prieto. 2015. "Gestural Codas Pave the Way to the Understanding of Verbal Irony." Journal of Pragmatics 90:26–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2015.10.002

Groeber, Simone, and Evelyne Pochon-Berger. 2013. "Turns and Turn-Taking in Sign Language Interaction: A Study of Turn-Final Holds." Journal of Pragmatics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2013.08.012

Gudmundsen, Jenny, and Jan Svennevig. 2020. "Multimodal Displays of Understanding in Vocabulary-Oriented Sequences." Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality 3(2). https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v3i2.114992

Heritage, John. 2012. "Epistemics in Action: Action Formation and Territories of Knowledge." Research on Language and Social Interaction 45(1):1–29.https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.646684

Hömke, Paul. 2018. "The Face in Face-to-Face Communication. Signals of Understanding and Non-Understanding." Ph.D. dissertation, Radboud University Nijmegen.

Kaukomaa, Timo, Anssi Peräkylä, and Johanna Ruusuvuori. 2013. "Turn-Opening Smiles: Facial Expression Constructing Emotional Transition in Conversation." Journal of Pragmatics 55:21–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2013.05.006

Kaukomaa, Timo, Anssi Peräkylä, and Johanna Ruusuvuori. 2014. "Foreshadowing a Problem: Turn-Opening Frowns in Conversation." Journal of Pragmatics 71:132–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.08.002

Kendrick, Kobin H. 2015. "The Intersection of Turn-Taking and Repair: The Timing of Other-Initiations of Repair in Conversation." Frontiers in Psychology 6:250. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00250

Kendrick, Kobin H., and Francisco Torreira. 2015. "The Timing and Construction of Preference: A Quantitative Study." Discourse Processes 52(4):255–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2014.955997

Koshik, Irene. 2005. Beyond Rhetorical Questions: Assertive Questions in Everyday Interaction. Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Kyle, Jim G., and Bencie Woll. 1985. Sign Language: The Study of Deaf People and Their Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Li, Xiaoting. 2014. "Leaning and Recipient Intervening Questions in Mandarin Conversation." Journal of Pragmatics 67:34–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.03.011

Li, Xiaoting, and Xiaoyung Wang. 2023/this issue. "Teacher Eyebrow and Head Movements as Repair-Initiation in Second-Language Classrooms." Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality 6(3).

Manrique, Elizabeth. 2016. "Other-Initiated Repair in Argentine Sign Language." Open Linguistics 2(1):1–34. https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2016-0001

Mondada, Lorenza. 2019. "Conventions for Multimodal Transcription (v. 5.0.1)."

Nota, Naomi, James P. Trujillo, and Judith Holler. 2021. "Facial Signals and Social Actions in Multimodal Face-to-Face Interaction." Brain Sciences 11(8):1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11081017

Ogden, Richard. 2020. "Audibly Not Saying Something with Clicks." Research on Language and Social Interaction 53(1):66–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1712960

Pelachaud, Catherine, Norman I. Badler, and Mark Steedman. 1996. "Generating Facial Expressions for Speech." Cognitive Science 20(1):1–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0364-0213(99)80001-9

Peräkylä, Anssi, and Johanna Ruusuvuori. 2012. "Facial Expression and Interactional Regulation of Emotion." Pp. 64–91 in Emotion in interaction, Oxford studies in sociolinguistics, edited by A. Peräkylä and M.-L. Sorjonen. New York: Oxford University Press.

Pomerantz, Anita. 1986. "Extreme Case Formulations: A Way of Legitimizing Claims." Human Studies 9(2–3):219–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00148128

Raymond, Chase Wesley. 2017. "Indexing a Contrast: The Do-Construction in English Conversation." Journal of Pragmatics 118:22–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2017.07.004

Roberts, Felicia, Alexander L. Francis, and Melanie Morgan. 2006. "The Interaction of Inter-Turn Silence with Prosodic Cues in Listener Perceptions of 'Trouble' in Conversation." Speech Communication 48(9):1079–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2006.02.001

Rossano, Federico. 2012. "Gaze Behavior in Face-to-Face Interaction." Ph.D. dissertation, Radboud University Nijmegen.

Rossi, Giovanni. 2020. "The Prosody of Other-Repetition in Italian: A System of Tunes." Language in Society 49(4):619–52. https://doi.org/10.1017=S0047404520000627

Sacks, Harvey, Emanuel A. Schegloff, and Gail Jefferson. 1974. "A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation." Language 50(4):696–735.

Sikveland, Rein Ove, and Richard Albert Ogden. 2012. "Holding Gestures across Turns: Moments to Generate Shared Understanding." Gesture 12(2):167–200.

Srinivasan, Ravindra J., and Dominic W. Massaro. 2003. "Perceiving Prosody from the Face and Voice: Distinguishing Statements from Echoic Questions in English." Language and Speech 46(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/00238309030460010201

Stivers, Tanya. 2004. "'No No No' and Other Types of Multiple Sayings in Social Interaction." Human Communication Research 30(2):260–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2004.tb00733.x

Stivers, Tanya, N. J. Enfield, Penelope Brown, Christina Englert, Makoto Hayashi, Trine Heinemann, Gertie Hoymann, Federico Rossano, Jan Peter de Ruiter, Kyung-Eun Yoon, and Stephen C. Levinson. 2009. "Universals and Cultural Variation in Turn-Taking in Conversation." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106(26):10587–92. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0903616106

Stivers, Tanya, and Federico Rossano. 2010. "Mobilizing Response." Research on Language & Social Interaction 43(1):3–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810903471258

Stolle, Sarah, and Martin Pfeiffer. 2023/this issue. "Facial Gestures as a Resource for Other-Initiation of Repair: The Role of Eyebrow Lowering." Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality 6(3).

Swerts, Marc, and Emiel J. Krahmer. 2010. "Visual Prosody of Newsreaders: Effects of Information Structure, Emotional Content and Intended Audience on Facial Expressions." Journal of Phonetics 38(2):197–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wocn.2009.10.002

de Vos, Connie, Els van der Kooij, and Onno Crasborn. 2009. "Mixed Signals: Combining Linguistic and Affective Functions of Eyebrows in Questions in Sign Language of the Netherlands:" Language and Speech. https://doi.org/10.1177/0023830909103177

Wittenburg, Peter, Hennie Brugman, Albert Russel, Alex Klassmann, and Han Sloetjes. 2006. "ELAN: A Professional Framework for Multimodality Research." in Proceedings of Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC).

1 Charlie's subsequent assertion that 'the issue of that w(h)eek w(h)as (0.2) him being on Question Time.' (l. 29–30) reinforces his point that the programme was by its very nature set up and thus not validly assessable as a normal programme.↩

2 The exact duration of the movement in Extracts 1 and 3 is not possible to establish because there is a cut to a different camera. The durations provided here are the minimum evidenced by the data.↩