Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Teachers' Eyebrow and Head Movements and Repeats as Other-Initiations of Repair in Second-Language Classrooms

Xiaoyun Wang & Xiaoting Li

University of Alberta

Abstract

This study investigates how teachers use language and bodily-visual practices, and particularly facial gestures, to initiate repair of problems in students' utterances in Chinese as a Second Language classroom interactions. We identify two multimodal practices used by teachers for other-initiation of repair. First, teachers use a "visual repair initiator" of eyebrow raises and head tilts to address apparent language errors in students' utterances without specifying the trouble-source. Second, teachers use full or partial repeats with marked prosody and eyebrow raises to display problems with accepting a student's response. We argue that the two practices are deployed to deal with different types of problems in students' utterances.

Keywords: other-initiation of repair, eyebrow movements, head movements, Chinese as a Second Language classroom interactions

1. Introduction

In everyday interaction, repair is used to maintain mutual understanding and deal with problems in speaking, hearing, understanding, or expectation (Egbert, 1996, 1997; Kim, 1999, 2001; Jefferson, 1974, 1987; Schegloff, 1979, 1987, 1992; Schegloff, Jefferson, & Sacks, 1977; Selting, 1996; Svennevig, 2008). In other-initiation of repair, the recipient of the trouble-source turn locates the trouble by initiating repair but leaves the repair to the producer of the trouble-source. Practices for other-initiation of repair have two tasks: locating the trouble-source and "categorizing" the trouble (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, 2018:139). Different practices of other-initiation of repair differ in their ability to locate the trouble-source and the effectiveness with which they do so (Egbert, 1996; Schegloff, Jefferson, & Sacks, 1977:369; Sidnell, 2010:118). For example, open class repair initiators (e.g., sorry? and huh? in English) are weaker forms of other-initiation that have a lower degree of specificity in locating the trouble-source in prior talk (Drew, 1997; Kendrick, 2015). In contrast, category-specific repair initiations which take the form of question-word interrogatives (e.g., who? and when? in English) are stronger other-initiation forms that show which type of information needs to be repaired (Schegloff, 2007). Repair-initiations which take the form of partially repeating the trouble-source or providing a candidate understanding directly locate the trouble-source (Clift, 2016; Robinson & Kevoe-Feldman, 2010; Schegloff, 1997). Schegloff et al. (1977) have argued that there is a preference for stronger other-initiation forms over weaker ones in everyday conversation. In classroom interaction, other-initiation of repair is commonly used by teachers to address problems in students' talk, not only for mutual understanding but also for student learning (e.g., Kasper, 1985; Liebscher & Dailey-O'Cain, 2003; McHoul, 1990; Mortensen, 2016; Seedhouse, 2004). However, in classroom interaction, the deployment and preferences of other-initiation forms seem to be relevant to other interactional-pedagogical factors (see a literature review in Section 2). This paper investigates how teachers' repair initiations are used to accomplish pedagogical tasks, and how teachers use verbal, vocal, and bodily-visual resources, and particularly facial gestures, to initiate repair in Chinese as a Second Language (CSL) classrooms.

In this study, we identify two multimodal practices for other-initiation of repair involving raised eyebrows performed by teachers in our CSL classroom data. One practice is an embodied repair initiator of eyebrow raising and head tilting without specifying the trouble-source verbally; the other practice is repeats produced with marked prosody and raised eyebrows. The two practices differ in their strengths in locating the trouble-source and the tasks they are used to accomplish. The first practice indicates teachers' orientation to students' talk as having language errors that the students may be able to locate and repair themselves, whereas the second practice displays teachers' problems with expecting or accepting the repeated elements in students' prior talk. By focusing on the participants' orientation to teacher-initiated repairs, our analyses also examine how students respond to different types of repair initiations and the relation this has to the problems needing repair.

2. Repair in Second Language Classrooms

To analyze the functions of teachers' multimodal practices for repair initiation, it is necessary to analyze the sequential positions of those practices. Different from everyday conversation in which the basic form of a sequence is an adjacency pair consisting of two adjacent turns (Schegloff, 2007), classroom interaction typically has a three-part sequence, called Initiation-Response-Evaluation (henceforth IRE) (Mehan, 1979). An IRE sequence is composed of a teacher question (Initiation), followed by a student answer (Response), and then teacher feedback (Evaluation). In classroom interaction, teachers produce other-initiation of repair in the third position of an IRE sequence, following a student's response turn. It has been argued that the third-positioned teacher's repair initiation is a type of teacher's interpretation of the student's answer (e.g., van Lier, 1994; Lee, 2007).

In second language (henceforth SL) classroom interaction, repair-initiations that have more specificity (i.e., candidate understanding and partial repetition) are commonly used by teachers (Egbert, 1997) and preferred by students (Liebscher & Dailey-O'Cain, 2003). Liebscher and Dailey-O'Cain (2003), however, argue that teachers use different types of repair initiators to negotiate meaning and form, which reflects the teachers' and students' roles in classroom interaction. The authors report that using open class repair initiators shows that teachers signal their and students' respective roles as teachers and learners in classrooms. Kasper (1985) also shows that the preferences of repair-initiation forms can be different in language-centered and content-centered activities. Open class repair initiators are less appropriate in focus-on-form activities than focus-on-meaning activities, since they identify the target of the trouble-source less specifically (Seedhouse, 2004). These studies (Kasper, 1985; Liebscher & Dailey-O'Cain, 2003; McHoul, 1990; Seedhouse, 2004) demonstrate that the institutional setting of SL classrooms routinely shapes the preferences and linguistic forms of other-initiation of repair.

A variety of linguistic and bodily-visual forms of other-initiation of repair used by teachers have also been documented in SL classrooms. Koshik (2005), for example, discusses the teacher's use of alternative interrogatives to present candidate hearing or understanding and to request a clarification of a prior utterance. Kääntä (2010) reports that teachers' repair-initiation can be an embodied action (through embodied and material devices) when it is produced in overlap with a student's answer. Similarly, Mortensen (2016) documents that the gesture of a cupped hand behind the ear can be used independently from verbal speech to display that a teacher treats a prior student answer as problematic. Seo and Koshik (2010) further describe two types of head movements: a head poke forward and a head tilt to the side, both of which can be used to initiate repair by both tutors and tutees to display their problems in understanding prior talk. The authors report that the head movements are produced after a possible completion of turn constructional units and held until the closure of the repair sequence. However, the way in which teachers' facial gestures that are concurrent with other multimodal resources are used as repair practices has not been fully discussed.

In terms of the functions of facial expressions in interaction, it has been argued that facial expression is a multimodal resource that can be used for displaying affects/emotions (e.g., Couper-Kuhlen, 2009; Goodwin & Goodwin, 2000; Peräkylä & Sorjonen, 2012). For example, surprise can be displayed through marked prosody, including wide pitch span and increased loudness (Couper-Kuhlen, 2020; Local, 1996; Selting, 1996), repetitions (Jefferson, 1972; Wilkinson & Kitzinger, 2006), and facial expressions (Ekman, 1992). Plutchik (1980) and Ekman (1992) have documented that raised eyebrows and an open mouth are relevant to displaying surprise. Particularly relevant to the current study is research on the use of eyebrow movements and bodily holds in signaling communicative problems and on other-initiation of repair in both spoken and signed languages. In everyday spoken interaction, it has been reported that eyebrow movements, including eyebrow raises and eyebrow furrows, can be used to mark expectation, hearing, or understanding problems (Enfield et al., 2013; Kaukomaa et al., 2014; Hömke, 2019). In signed interaction, Manrique (2016) shows that eyebrow movements are used in other-initiation of repair. Manrique and Enfield (2015) report that a "freeze-look," that is, a bodily hold, is a practice for other-initiation of repair in Argentinian signed language. It is produced by the recipient of a question to initiate repair, which results in the questioner re-doing their prior question. Bodily holds (such as a hold of raised eyebrows) accompanying repair initiation have been described to display that a repair is anticipated in both spoken and signed interactions (Floyd et al., 2016).

Building on previous research on the verbal and visual repair initiation practices in everyday and classroom interactions, this study examines multimodal practices for other-initiation of repair used by teachers in CSL classrooms.

3. Data and Methods

3.1 Data and participants

The data for the study are 12 hours of video recordings collected from ten CSL classrooms. They were collected at a university in Beijing, China, in 2019. The ten classes were of various levels and types, including three advanced classes, three intermediate classes, and four beginner classes. The language skills involved in the ten classes included reading, listening, and speaking. Three of the ten classes were intensive reading; one was spoken Chinese; one focused on listening and spoken Chinese; four were comprehensive Chinese; and one was business Chinese.

The participants in this study were ten Mandarin native speaker teachers and 137 Chinese language learners from various native language backgrounds, with students' ages ranging from 20 to 30 years old. The length of their Chinese language learning and their stay in China ranged from half a year to more than two years. The age range of the teachers was from 20 to 40 years old.

3.2 Methods and coding

Our analysis follows the methodology of multimodal conversation analysis (Deppermann, 2013) and interactional linguistics (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, 2018). We study the design and functions of teachers' repair initiation by analyzing their morphosyntactic, prosodic, and bodily-visual features, as well as teachers' and students' orientations to repair initiation (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, 2018; Goodwin & Heritage, 1990; Stivers & Sidnell, 2005; Streeck, Goodwin, & LeBaron, 2011). In this study, we focus our bodily-visual analysis on teachers' facial gestures and body movements. Students' bodily-visual movements are only discussed when they are relevant to our analytical focus.

The data in this study were transcribed using two transcription systems: the GAT-2 (Gesprächsanalytisches Transkriptionssystem 2, Selting et al., 2009) transcription system, modified according to Li (2019) (see Appendix) for the verbal channel for Mandarin, and a multimodal transcription system based on C. Goodwin (2018) and Kendon (2004). Prosodic features were identified through auditory analysis, assisted by the acoustic analysis software program PRAAT (Boersma & Weenink, 2022). Bodily-visual movements were analyzed using the video annotation software program ELAN (Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, 2022).

4. Teachers' Eyebrow Raises and Head Movements as (Part of) Repair-Initiation

This section reports on two practices for other-initiation of repair involving eyebrow and head movements used by teachers in our CSL classroom data. The first practice is a hold of eyebrow raises and head tilt with no verbal elements. The second practice consists of teachers' eyebrow raises concurrent with partial repeats: [partial repeats + eyebrow raises]. Both practices are deployed after a student's response and both adumbrate different problems that teachers have with respect to students' responses to teachers' prior questions. The first practice of bodily-visual hold is a practice deployed by teachers to address language problems in students' responses. That is, through holding eyebrow raises and head tilts with no accompanying speech, teachers mark students' responses as containing evident language errors without verbally specifying them. In this way, the teachers provide students with an opportunity to detect and correct their prior language errors themselves. The second practice [partial repeats + eyebrow raises] displays that teachers treat the student's answer as a departure from their expectations. The facial gestures and concurrent verbal repeats serve to signal the problems in the student's answer while displaying the teacher's surprise (Wilkinson & Kitzinger, 2006; Selting, 1996). We discuss the teachers' uses of these two practices for repair initiations in detail in Sections 4.1 and 4.2.

4.1 Using the hold of eyebrow raises and head tilt as repair initiation to address language errors

In our CSL classroom data, holding eyebrow raises was combined with head movements to initiate repair. This type of nonverbal repair initiation is deployed by the teachers to address language errors (such as pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar) in students' answers. Specifically, the teachers raise their eyebrows while tilting their heads sideways immediately after students' turns containing language errors; the teachers hold the eyebrow raises and head tilts until the students realize that a self-correction is expected (Excerpt 1) or until the teacher reformulates their prior questions to provide students with another opportunity to correct (Excerpt 2). Since teachers do not specify the trouble-source in the student's response through this nonverbal strategy, students have to identify the problem themselves. Consequently, students may (see Excerpt 1) or may not (see Excerpt 2) immediately detect the problem and perform repair after the teacher's nonverbal repair initiator.

Excerpt 1 provides an example of how the teacher holds the eyebrow raises and head tilt after a student's language error as a nonverbal practice for initiating repair. The excerpt is taken from a review activity in an advanced CSL class where the class is reviewing the reading material that they have learned in a prior class. In lines 1 and 2, the teacher has selected StA to retell an utterance of a character (referred to as ta, 'he,' in line 15) from their reading material, in which the character says that he has no 'vigor' without eating breakfast. In her answer, jingshen, 'vigor' (line 17), is pronounced with an incorrect stress and tone. That is, the student puts the stress on the second syllable shen instead of the first one jing. In Modern Standard Chinese, when expressing the meaning of 'vigor,' the second syllable shen is unstressed (Xiandai Hanyu Cidian "Modern Chinese Dictionary" 5th Edition, 2005:721). Unstressed syllables have a "neutral tone" (Chao, 1968:36), which does not have any prescribed pitch contours (or lexical tones) (Li & Thompson, 1981:9). The student produces the syllable shen with a high-level tone (Tone 1 in Mandarin phonology), which is incorrect. The teacher eventually produces the correct pronunciation of the word 'vigor' (with stress on the first syllable and neutral tone on the second syllable) in line 25, retrospectively rendering the problem in the student's response in lines 15 and 17 as being one of pronunciation.

Excerpt 1. Vigor

Open in a separate window

Immediately after the student's shen in line 17, the teacher raises her eyebrows and tilts her head to the left side while looking at the student (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). Immediately after the teacher's look, the student looks down at the reading materials on her desk, possibly to check for the relevant words and sentences (Figure 1.4). The teacher holds her raised eyebrows and tilted head during the student's search for 1.4 seconds (line 18, Figures 1.2 and 1.3) and produces a freestanding dental click (line 19), displaying an affect of disapproval (see Ogden, 2020, for freestanding clicks used to display affective stance). The click here together with the hold of the eyebrow raises and head tilt occur after the student's response, which displays the teacher's orientation to the student's response in lines 15 and 17 as having problems and seeking the student's self-correction. Immediately after the teacher lowers her eyebrows and moves her head to the home position (Figure 1.5), the student produces the "change-of-state" token ou, 'oh,' (line 20, Figure 1.6) and performs the repair (lines 21–24). However, instead of correcting the mispronounced word jingshen (line 17), the student reformulates the entire sentence with an added conjunction ranhou, 'then,' and changes the main verb (from yao, 'want,' line 15) to meiyou, 'not have' (line 22). The problem is finally explicated by the teacher in line 25 and resolved after the student's repeat of the correct pronunciation (line 26) and the teacher's feedback (line 27) and explanation (line 28).

Here, the teacher's raising of her eyebrows and the hold of her eyebrow raise and head tilt after the student's response display the teacher's treatment of the response as problematic, thereby initiating repair (Floyd et al., 2016). However, in contrast to most other forms of repair initiation (with the exception of open class repair initiators, Drew, 1997), the nonverbal repair initiation observed here does not specify the trouble-source. Thus, this nonverbal practice initiates repair and provides the student with an opportunity to identify and repair the repairable herself. When the student shows that she is not able to identify the problem (lines 20–24), the teacher explicitly corrects the language error and resolves the problem (lines 25, 27–28). This nonverbal practice of repair initiation is particularly usable for teachers to address obvious language errors in a student's utterance.

Excerpt 2 provides another case of how teachers use raised eyebrows and head tilts to initiate a repair after a student response with language errors. This excerpt is taken from an advanced reading course in which the teacher is checking students' understandings of the word qunzhong, 'multitude.' Prior to the sequence, the teacher has explained the meaning of qunzhong. In Modern Standard Chinese, qunzhong, 'multitude,' can be used to label the political identity of people who are not members of the Chinese Communist Party or the Communist Youth League (Xiandai Hanyu Cidian "Modern Chinese Dictionary" 5th Edition, 2005:1137). In this excerpt, the teacher asks the students who the crowd (qunzhong, 'multitude') is as far as the Chinese Communist Party is concerned (lines 1–2). StA provides his answer: suoyou ren, 'all people/everyone' (line 4), which is problematized by the teacher (lines 6–10). Eventually, StB provides the correct answer: laobaixing, 'civilians,' in line 12.

Excerpt 2. Multitude

Open in a separate window

After StA's response in line 4, the teacher raises her eyebrows and tilts her head to her left (Figures 2.1 and 2.2). She then holds her raised eyebrows and tilted head while looking at StA for 1.7 seconds (line 5). The teacher's hold of her facial gesture and head movement display that the teacher treats StA's answer as problematic, which makes relevant a repair and provides StA with another opportunity to re-produce his answer. StA keeps a straight face and looks at the teacher during the silence (in line 5, Figures 2.3). He does not verbally react to the teacher's repair initiation, possibly due to inability to identify the language error. After waiting for 2.5 seconds, none of the students produce a self-repair (see the 2.5-second silence in line 5 after the teacher's repair initiation). The teacher provides an example by adopting the footing (Goffman, 1974) of a Communist Party member through using the first-person pronoun wo, 'I' (lines 6-9). After the example, the teacher provides another opportunity for the students to answer her prior question (in lines 1–2) by asking the students the meaning of qunzhong, 'multitude' (line 10). This time, her question is answered by StB in line 12. The teacher adopts StB's answer: laobaixing, 'civilians,' and states that laobaixing, 'civilians,' are not gongchandang, 'Communists' (line 16). Here through the hold of eyebrow raises and the head tilt, the teacher elicits StA to repair his prior answer without specifying what the trouble-source is. However, unlike in Excerpt 1, the student does not produce the repair, which shows that he has not identified the language error.

Excerpts 1 and 2 show how (the hold of) raised eyebrows and head tilts are used by the teacher to display their orientation to the student response as containing a language error, thereby prompting students to repair their answer. While the visual repair initiator does not locate or categorize the trouble-source, the non-specifying nature of the visual practice makes it particularly useful for marking the trouble as more easily detectable (or at least treated as such by teachers) "lower-level" language errors, such as pronunciation errors (Excerpt 1) and lexical errors (Excerpt 2).

4.2 Using repeats, eyebrow raises, and marked prosody as repair initiation to address problems of acceptability

In the second type of repair initiation, teachers use verbal repeats, eyebrow raises, and marked prosody to initiate repair. This practice for other-initiation of repair displays the teacher's problem with accepting the repeated elements in the student's response to the teacher's prior question with respect to its facticity (Excerpt 3) or appropriateness (Excerpt 4). In our data, one type of problem with students' responses is an expectation problem. For example, a student's response may be grammatically-phonologically correct/acceptable and sequentially fitted but contain a pragmatically deviant expression that departs from a native speaker's common expectation.

Turn-at-talk consisting of (full or partial) repeats concurrent with eyebrow raises and marked prosody indicates the teacher's problem with accepting elements in the student's response. This initiation of repair further serves to request the student's explanation of or account for their prior response. This can be observed in Excerpt 3, taken from an intermediate Chinese course. The sequence begins with the teacher's question, asking what colors grapes are (line 1). Multiple students provide their answers to the question by listing different colors of grapes, such as purple (line 3), green (line 6), and red (lines 7 and 9). StD's response (line 10) is treated as problematic by the teacher, as is shown through the teacher's repair initiation (line 11).

Excerpt 3. Grapes

Open in a separate window

StD's answer (line 10), haiyou heise, 'also have black,' is grammatically and phonologically correct. Specifically, the lexical construction haiyou, 'also have,' is used to extend the range of lexical items (i.e., colors of grapes) that have been mentioned (Lü, 1999:252). The NP heise, 'black color,' (line 10) is grammatically fitted after haiyou, 'also/also have.' StD also produces line 10 with the correct pronunciation. However, in line 11, the teacher's repeat of the student's answer shows that she treats this answer as problematic. The teacher employs repeats, a stronger repair initiation format, to locate the trouble-source in the student's answer (Schegloff et al., 1977:369), while raising her eyebrows (Figure 3.1). The repeat and the eyebrow raise display the teacher's surprise at the student's response (Ekman, 2004; Plutchik, 1980), possibly indicating that the student's response conflicts with the teacher's belief about what is true regarding the possible colors of grapes (see Selting, 1996, for repeats as displays of astonishment). Other students' laughter (line 12) also shows a similar orientation to StD's response in line 10. In line 13, StC provides a repair by affirming the truthfulness of StD's response that there are black grapes. StC's defense of StD's response shows that she treats the teacher's repair initiation, a repeat accompanied by an eyebrow raise in line 11, as questioning the facticity of StD's response. In line 14, the teacher provides a candidate understanding about the trouble-source, that is, "it is a purple as dark as black." To provide candidate understanding is a stronger format of repair-initiation (Svennevig, 2008). After StD explains that black grapes are a "very deep purple" (line 16), the teacher agrees with StD's account through an agreement token, dui, 'right' (line 17), and rephrasing the account (line 18). The teacher's agreement with and rephrasing of StD's account demonstrate her acceptance of StD's prior response (line 10) as a semantically and pragmatically fitted response to her prior question.

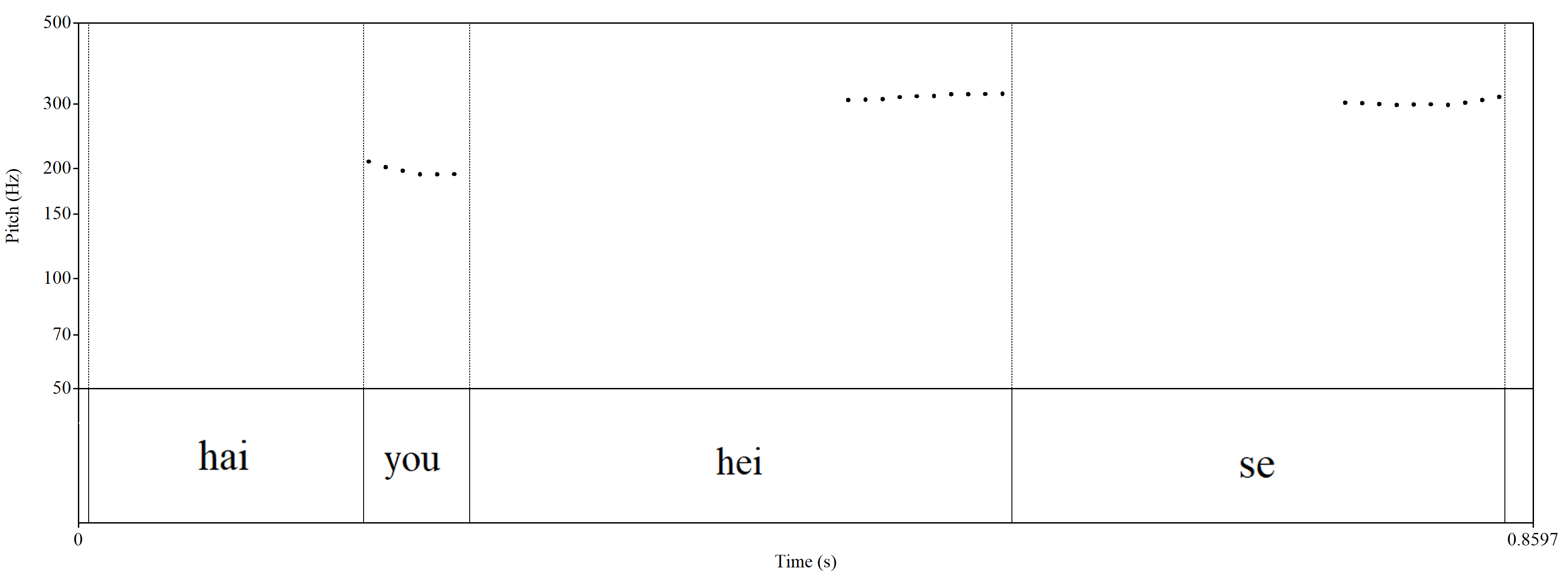

In addition, the teacher's turn in line 11 is also produced with a "marked prosody." For example, the final syllable se in line 11 is produced with rising pitch movement with a high pitch register (Figure 3.2). This is especially marked given that the pitch contour of the lexical item se, 'color,' is high falling in Mandarin phonology. In repeating the trouble-source with final rising intonation, the teacher displays her disbelief toward the repeated utterance (see also Wu, 2006).

Figure 3.2. Pitch trace (dotted line) of the teacher's turn in line 11 in Excerpt 3

Excerpt 4 is another case in point. In this excerpt, the teacher is guiding the students to practice using a new word: mianlin, 'facing… some challenges' (the first word in line 1). The sequence begins with the teacher's question, asking students to provide a solution to the issue of shortages of fresh water (lines 1 and 3). StA selects herself as the next speaker and produces her answer in lines 5 and 6.

Excerpt 4. Facing challenges

Open in a separate window

In line 6, StA's answer to the teacher's question, women yinggai you gengshao ren, "we should have less people," is grammatically and phonologically correct. In line 7, the teacher partially repeats the student's answer in line 6 you gengshao ren, "have less people," which indicates a trouble-source needing repair (Wu, 2006). The sequential position of this repair initiation is after a student's response. StA orients to the teacher's utterance in line 7 as a repair initiation, as she provides an explanation to her prior answer in line 8. After receiving the student's explanation, the teacher rephrases the solution of the problem as "to control the population" in line 10.

The main verb in the student's response in line 6: you, 'have,' indicates ownership or existence, and thus is a verb conveying a low degree of disposal: "The disposal form states how a person is handled, manipulated, or dealt with; how something is disposed of; or how an affair is conducted" (translation of Wang Li, 1947, cited in Li & Thompson, 1981:468. Also see Li & Thompson, 1981, Chapter 15 for more on the notion of disposal). In contrast, the teacher's question, women yinggai zenmeban, "What should we do?" (lines 1 and 3), requires a response that offers solutions with verbs conveying a high degree of disposal. Note that in her reformulation of StA's response in line 10, the teacher uses the VP kongzhi renkou, "control the population," with the verb kongzhi, 'control,' conveying a high degree of disposal, which proposes a solution to the challenge. Thus, although StA's response in line 6 is grammatically and phonologically well formed, it does not directly provide a solution; rather, it causes a misunderstanding that the existing people can be disowned or reduced. The teacher's repair initiation (line 7) displays her problem with accepting that part of StA's utterance is an appropriate response to the teacher's prior question. Immediately after the teacher's partial repeat in line 7, StA provides an account for her prior response that the population is too large (line 8), which shows that she treats the teacher's partial repeat in line 7 as a request for an explanation.

While producing the partial repeat, the teacher performs facial gestures and other bodily-visual movements displaying acceptability of her problem with the student's response. She raises her eyebrows while leaning forward and producing a head poke (see Figure 4.1). Raised eyebrows are visual displays of surprise (Ekman, 2004; Plutchik, 1980), which render the repeated element in the student's response as unexpected (Selting, 1996). Leaning forward toward the recipient has been documented as a practice that co-occurs with intervening questions that seek response in everyday conversation (Li, 2014). In SL classroom interaction, head pokes accompanying upper-body leaning forward toward the speaker of the trouble-source have been observed being used together with verbal repair-initiation by SL teachers (Seo & Koshik, 2010).

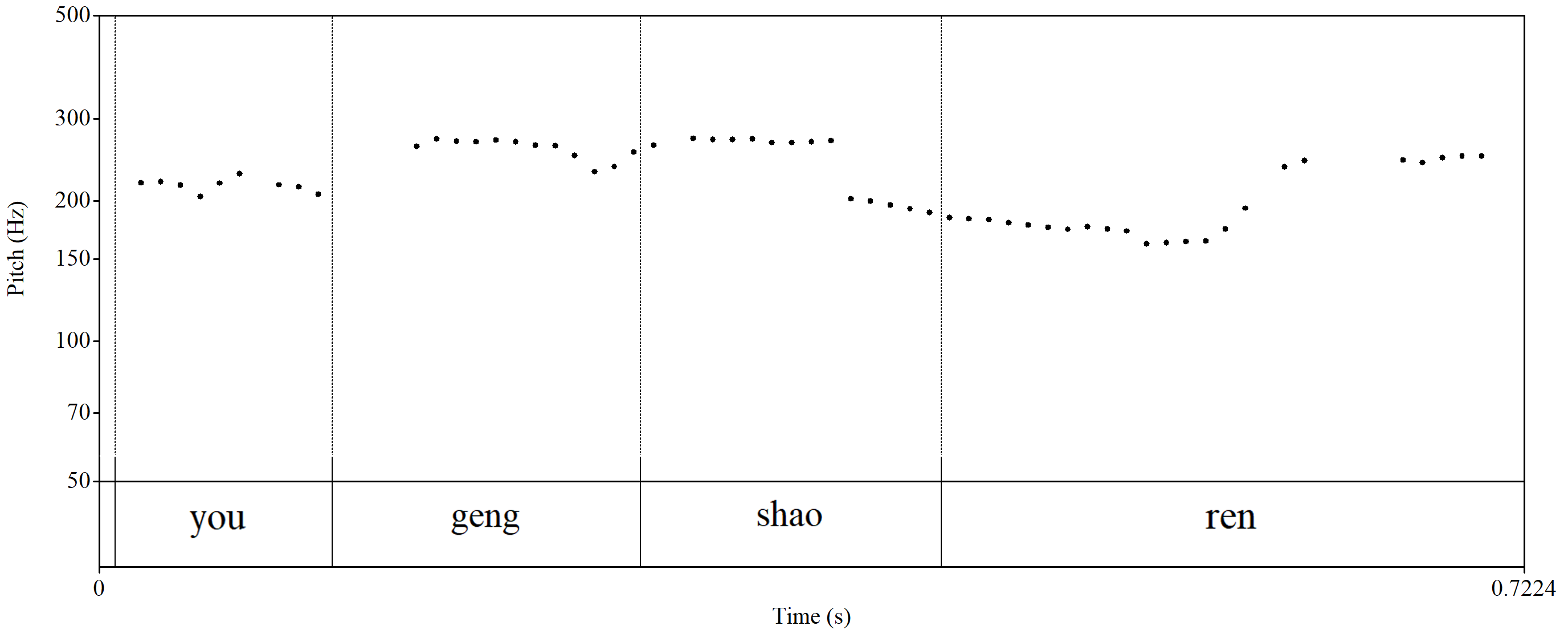

The teacher's turn in line 7 is further produced with a "marked prosody" similar to that observed in Excerpt 3, realized as a high pitch register and a wide pitch range on the last syllable ren, 'person,' indicating astonishment. Her turn in line 7 is produced with a high rising final pitch movement with a high pitch register (Figure 4.2). Wu (2006: 85) states that "question-intoned repeats" (i.e., repeats with final rising intonation) as repair initiation convey unexpectedness. The lexical tone of the last syllable in line 7, ren, 'people,' is high rising in Mandarin. But the noticeably high rising pitch movement reflected in the extremely wide pitch range of the syllable ren (6.8 semitones, compared to 2 ST of you, 2.3 ST of geng, and 3 ST of shao) is a prosodic marker of surprise in our data (see Selting, 1992, 1996 for rising pitch movement as a prosodic marker of astonishment in German conversation).

Figure 4.2. Pitch trace (dotted line) of the teacher's turn in line 7 in Excerpt 4

The repair initiations analyzed in this section are constituted through the multimodal resources of (partial) repetition and eyebrow raises. This practice is deployed after a student response that is treated as unexpected or unacceptable by the teacher. After the teachers repeat the trouble-source with their eyebrows raised, the students produce the repair through either reaffirming the facticity of their response (Excerpt 3) or providing an explanation for their response (Excerpt 4). In comparison with language errors (such as pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar, which have been analyzed in Section 4.1), expectation problems (Excerpts 3 and 4) are higher-level pragmatic, knowledge, or understanding problems. Excerpts 3 and 4 show how teachers use repeats with eyebrow raises as a stronger repair initiation format for locating the trouble-source and addressing higher-level expectation problems.

5. Concluding Discussions

In this paper we have shown how teachers in CSL classrooms use two multimodal practices for initiating repair to different problems in students' utterances in our data of CSL classroom interactions. Specifically, teachers use the repair initiator of eyebrow raises and head tilts to categorize the problem of a student's utterance containing self-evidenced language errors such as mispronounced (Excerpt 1) or misused words that students have already learned (Excerpt 2). Alternatively, teachers use full or partial repeats with marked prosody and eyebrow raises to display problems with accepting the repeated elements in a student's response to the teacher's prior questions (Excerpts 3 and 4). The eyebrow raise and head movement seem to serve different functions between/within the two practices. When performed without talk, the teacher's eyebrow raises and head tilts mark the student's answer containing easily detectable language errors. When concurrent with verbal repeats in the second practice, the teacher's eyebrow raises display their surprise at the repeated elements of the students' responses, which renders the repeated talk as unexpected. The focus of this paper is the multimodal repair practices that are produced by teachers, not the repairs that are constructed by students. Therefore, the students' facial and body movements are only analyzed when they are relevant to our main arguments regarding repair practices that are produced by teachers.

This study demonstrates that multimodal resources are deployed together to accomplish teachers' repair initiations, while resources of different modalities seem to serve different interactional purposes (Keevallik, 2018). In other words, in our data initiating repair is a complex action in which teachers face multiple interactional tasks. This study shows that a lexical-syntactic resource, that is, repeats, can serve to make the trouble-source recognized. On the other hand, marked or unmarked prosody, cooccurring with eyebrow raises, mouth-opening, and head poke may signal whether a teacher treats the repairable as departure from their expectation (Selting, 1996). Although focusing our analysis on these described multimodal resources, we do not deny that other resources, such as gaze and body orientation, may also play a role in organizing students' participation and engagement in producing repairs (see Goodwin, 1986; Stivers & Rossano, 2010). The observations reported in this study embrace previous multimodal research which argues that action and interaction are constructed by integrating various semiotic resources (Goodwin, 2013, 2017).

The findings of this study contribute to the research on other-initiation of repair in general and in second language classroom interaction and pedagogy. First, the two multimodal practices and their treatments indicate systematic relationships between the type of repair initiation and the type of repair. The visual repair initiator of [eyebrow raises + head tilt] marks the student's prior utterances as containing apparent errors and prompts the student to locate and repair their own errors. Unlike verbal repeats, the visual repair initiator does not locate the trouble-source, leaving it to students to identify their own particular errors. However, by virtue of not verbally locating or specifying the problem in a student's utterance, teachers demonstrate that they treat the detection of the problem as possibly within the student's ability, based on their prior linguistic knowledge. The nature of this visual repair initiator has implications for second language teaching and learning, which will be discussed in the subsequent paragraphs. Depending on students' linguistic knowledge, they may (Excerpt 4) or may not (Excerpt 3) produce a repair immediately after the teacher's visual repair initiation. Repeats produced with marked prosody and eyebrow raises are designed by teachers and treated by students as dealing with problems of acceptability of students' responses to teachers' prior questions. After teachers' repeats with eyebrow raises, students produce repair through either stating the facticity of their prior response (Excerpt 3) or providing accounts for their response (Excerpt 4). Both forms of repair show that students treat the repair initiator as displaying the teacher's doubt about or pre-disagreement with their prior responses (see Schegloff, 2007, for pre-disagreement). Both teachers and students display orientations to the two repair practices as dealing with different types of problems.

Furthermore, the two practices for other-initiation of repair documented in our CSL classroom interactional data have implications for SL pedagogy, particularly how SL teachers deal with different types of errors or problems in students' utterances. We have shown that raised eyebrows and head tilts are deployed to display teachers' orientation to a student's utterance as having apparent language errors such as mispronounced (Excerpt 1) or misused (Excerpt 2) words. In contrast, repeats produced with marked prosody and raised eyebrows are used to display teachers' orientation to a student's response as being unexpected or unacceptable. When expectation problems arise as a result of a student's deviant response to teachers' prior questions, such as responses that exhibit conflict with facticity (Excerpt 3) or that are inappropriate (Excerpt 4), students may or may not treat the problems as such through their repairs. Compared to problems in higher-level linguistic skills, such as reparation of expectation problems, errors in pronunciation and vocabulary production of what students have already learned involve lower-level linguistic skills that are arguably easier to locate and repair. This distinction is reflected in the different practices that teachers use to deal with the two different types or levels of linguistic problems in students' utterances. Specifically, the repair initiation format that can locate the trouble-source (Schegloff et al., 1977; Sidnell, 2010:118) is used to address higher-level expectation problems, and the repair initiation format of [raised eyebrows + head tilt] without verbally locating the trouble-source is used to address lower-level pronunciation and vocabulary errors. The way that raised eyebrows and head tilts are used to initiate repair makes the practice particularly useful in addressing lower-level language errors. By avoiding locating the trouble-source, teachers provide the student with an opportunity to detect and diagnose a problem and to correct it themselves. In our data, only when students failed to locate and correct a language error would a teacher correct it herself (see Excerpt 1). Thus, this study shows a relationship between different repair initiation practices and the different types of linguistic errors they are used to address, and different opportunities they afford students in their SL learning.

Acknowledgements

A previous version of this paper was presented at the 2nd International Workshop of Facial Gestures in Social Interaction in 2021. We would like to thank the editors of this volume, Alexandra Groß and Carolin Dix, as well as two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, and Kerry Sluchinski for her appreciated editorial assistance.

References

ELAN (Version 6.3) [Computer software]. (2022). Nijmegen: Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, The Language Archive. Retrieved from https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/elan

Xiandai Hanyu Cidian 现代汉语词典 Modern Chinese Dictionary. 5th Edition, 2005. Beijing: Commercial Press.

Boersma, P. & Weenink, D. (2022). Praat: doing phonetics by computer [Computer program]. Version 6.2.13, retrieved 18 May 2022 from http://www.praat.org/

Chao, Y. (1968). A grammar of spoken Chinese. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Clift, R. (2016). Conversation analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2009). A sequential approach to affect: The case of "disappointment." In M. Haakana, M. Laakso, & J. Lindström (Eds.), Talk in interaction—Comparative dimensions (pp. 94-123). Helsinki, Finland: SKS Finnish Literature Society.

Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2020). The prosody of other-repetition in British and North American English. Language in Society, 49(4): 521-552.

Couper-Kuhlen, E. & Selting, M. (2018). Interactional linguistics: Studying Language in Social Interaction. Cambridge University Press.

Deppermann, A. (2013). Multimodal interaction from a conversation analytic perspective. Journal of Pragmatics, 46(1): 1-7.

Drew, P. (1997). "Open" class repair initiators in response to sequential sources of troubles in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 28: 69-101.

Egbert, M. (1996). Context-sensitivity in conversation: Eye gaze and the German repair initiator bitte? Language in Society, 25(4): 587-612.

Egbert, M. (1997). Some interactional achievements of other-initiated repair in multi-person conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 27: 611-634.

Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 6, 169-200.

Ekman, P. (2004). Emotional and Conversational Nonverbal Signals. In: Larrazabal, J., Miranda, L. (Eds.), Language, Knowledge, and RepresentationEkman, P. (2004). Emotional and Conversational Nonverbal Signals. In: Larrazabal, J., Miranda, L. (Eds.), Language, Knowledge, and Representation. Philosophical Studies Series (pp. 39-50), 99. Dordrecht: Springer.. Philosophical Studies Series (pp. 39-50), 99. Dordrecht: Springer.

Enfield, N., Dingemanse, M., Baranova, J., Blythe, J., & Brown, P. (2013). Huh? What? - A first survey in 21 languages. In: Hayashi, M., Raymond, G., & Sidnell, J. (Eds), Conversational Repair and Human Understanding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Floyd, S., Manrique, E., Rossi, G., & Torreira, F. (2016). The timing of visual bodily behavior in repair sequences: evidence from three languages. Discourse Process. 53: 175-204.

Goodwin, C. (1986). Gestures as a resource for the organization of mutual orientation. Semiotica, 62(1-2): 29-49.

Goodwin, C. (2013). The co-operative, transformative organization of human action and knowledge. Journal of pragmatics, 46(1), 8-23.

Goodwin, C. (2017). Co-Operative Action. Cambridge University Press.

Goodwin, C. (2018). Why multimodality? Why co-operative action? Social Interaction: Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 1(2).

Goodwin, C. & Goodwin, M. H. (2000). Emotion within situated activity. In A. Duranti (Ed.), Linguistic anthropology: A reader (pp. 239-257). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Goodwin, C. & Heritage, J. (1990). Conversation analysis. Annual Review of Anthropology, 19: 283-307.

Hömke, P. (2019). The face in face-to-face communication: Signals of understanding and non-understanding [Doctoral dissertation]. Radboud University Nijmegen.

Jefferson, G. (1972). Side sequences. In D. N. Sudnow (Ed.), Studies in Social Interaction (pp. 294-338). New York: The Free Press.

Jefferson, G. (1974). Error correction as an interactional resource. Language in Society, 2: 181-99.

Jefferson, G. (1987). On exposed and embedded correction in conversation. In: G. Button & J.R. Lee (Eds.), Talk and Social Organisation (pp. 86-100). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Kääntä, L. (2010). Teacher turn-allocation and repair practices in classroom interaction: a multisemiotic perspective [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Jyväskylä.

Kasper, G. (1985). Repair in foreign language teaching. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 7: 200-215.

Kaukomaa, T., Perakyla, A., & Ruusuvuori, J. (2014). Foreshadowing a problem: tum-opening frowns in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 71:132-47.

Keevallik, L. (2018). What does embodied interaction tell us about grammar? Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1): 1-21.

Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible Action as Utterance.

Kendrick, K. (2015). Other-initiated repair in English. Open Linguistics, 1(1): 164-190.

Kim, K. (1999). Other-initiated repair sequences in Korean conversation: Types and functions. Discourse and Cognition, 6(2): 141-68.

Kim, K. (2001). Confirming intersubjectivity through retroactive elaboration: Organization of phrasal units in other-initiated repair sequences in Korean conversation. In: M. Selting & E. Couper-Kuhlen (Eds.), Studies in Interactional Linguistics (pp. 345-372). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Koshik, I. (2005). Alternative questions in conversational repair. Discourse Studies, 7(2): 192-211.

Lee, Y. (2007). Third turn position in teacher talk: Contingency and the work of teaching. Journal of Pragmatics, 39(6): 1204-1230.

Li, C. & Thompson, S. (1981). Mandarin Chinese: A functional reference grammar. University of California Press.

Li, X. (2014). Multimodality, Interaction, and Turn-taking in Mandarin Conversation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Li, X. (2019). Researching multimodal Chinese interaction: a methodological account. In: X. Li, & T. Ono (Eds.) Multimodality in Chinese Interaction. De Gruyter Mouton.

Liebscher, G. & Dailey-O'Cain, J. (2003). Conversational repair as a role-defining mechanism in classroom interaction. The Modern Language Journal, 87: 375-390.

Local, J. (1996). Conversational phonetics: Some aspects of news receipts in everyday talk. In E. Couper-Kuhlen & M. Selting (Eds.), Prosody in Conversation (pp. 177-230). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lü, S. (1999). Eight hundred words in modern Chinese. Beijing: Commercial Press.

Manrique, E. (2016). Other-initiated repair in Argentine Sign Language. Open Linguistics, 2: 1-34.

Manrique E. & Enfield, N. (2015). Suspending the next turn as a form of repair initiation: evidence from Argentine Sign Language. Frontiers in Psychology, 6: 1-21.

Mehan, H. (1979). Learning lessons: Social organizations in the Classroom. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

McHoul, A. (1990). The organization of repair in classroom talk. Language in Society, 19: 349-377.

Mortensen, K. (2016). The body as a resource for other-initiation of repair: Cupping the hand behind the ear. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 49(1): 34-57.

Ogden, R. (2020). Audibly not saying something with clicks. Research on Language and Interaction. 53(1): 66-89.

Peräkylä, A. & Sorjonen, M. (Eds.) (2012). Emotion in interaction. New York: Oxford University Press.

Plutchik, R. (1980). Emotion: A psychoevolutionary synthesis. New York, Harper and Row.

Robinson, J. & Kevoe-Feldman, H. (2010). Using full repeats to initiate repair on others' questions. Research on Language and Social Interaction. 43: 232-259.

Schegloff, E. (1979). The relevance of repair to syntax-for-conversation. In T. Givon (Ed.), Syntax and Semantics 12: Discourse and Syntax (pp. 261-286). New York: Academic Press.

Schegloff, E. (1987). Some sources of misunderstanding in talk-in-interaction. Linguistics, 25(1): 201-218.

Schegloff, E. (1992). Repair after next turn: The last structurally provided defense of intersubjectivity in conversation. American Journal of Sociology, 97(5): 1295-1345.

Schegloff, E. (1997). Third turn repair. In: G. Guy, C. Feagin, D. Schiffrin, & J. Baugh, (Eds.), Towards a Social Science of Language: Papers in Honor of William Labov. Volume 2: Social Interaction and Discourse Structures (pp. 31-40). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Schegloff, E. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction: A primer in conversation analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schegloff, E., Jefferson, G., & Sacks, H. (1977). The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. Language, 53(2): 361-382.

Seedhouse, P. (2004). The interactional architecture of the language classroom: A conversation analysis perspective. Oxford: Blackwell.

Selting, M. (1992). Prosody in conversational questions. Journal of Pragmatics, 17(4): 315-345.

Selting, M. (1996). Prosody as an activity-type distinctive cue in conversation: the case of so-called "astonished" questions in repair initiation. In: E. Couper-Kuhlen & M. Selting (Eds.), Prosody in Conversation: Interactional Studies (pp. 231-270). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Selting, M., Auer, P., Barth-Weingarten, D., Bergmann, J. R., Bergmann, P., Birkner, K., Couper-Kuhlen, E., et al. (2009). Gesprächsanalytisches Transkriptionssystem 2 (GAT 2). Gesprächsforschung - Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion, 10, 353-402.

Seo, M. & Koshik, I. (2010). A conversation analytic study of gestures that engender repair in ESL conversational tutoring. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(8): 2190-2239.

Sidnell, J. (2010). Questioning repeats in the talk of four-year old children. In: H. Gardner & M. Forrester (Eds.), Analysing Interactions in Childhood: Insights from Conversation Analysis (pp. 103-127). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Stivers, T. & Rossano, F. (2010). Mobilizing response. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 43(1): 3-31.

Stivers, T., & Sidnell, J. (2005). Introduction: multimodal interaction. Semiotica, 156, 1-20.

Streeck, J., Goodwin, C., & LeBaron, C. (Eds.) (2011). Embodied interaction: Language and Body in the Material World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Svennevig, J. (2008). Trying the easiest solution first in other-initiation of repair. Journal of Pragmatics, 40: 333-348.

van Lier, L. (1994). The classroom and the language learner. Ethnography and second-language classroom research. London: Longman.

Wang, Li 王力. (1947). 中国现代语法 Modern Chinese Grammar. Shanghai: Zhonghua Shuju.

Wilkinson, S. & Kitzinger, C. (2006). Surprise as an interactional achievement: Reaction tokens in conversation. Social Psychology Quarterly, 69(2):150-82.

Wu, R. (2006). Initiating repair and beyond: The use of two repeat-formatted repair initiations in Mandarin conversation. Discourse Processes, 41(1): 67-109.

Appendix - Transcription Conventions

| Symbol | Meaning |

| [ ] | Overlap |

| (0.4) | Pause duration in seconds and tenth seconds |

| (.) | Micro-pause |

| (-), (--), (---) | short, middle or long pauses of 0.2-0.8 seconds, up to 1 second |

| :, ::, ::: | lengthening of 0.2-0.8 seconds |

| , | Rising pitch movement of intonation unit |

| - | Level pitch movement of intonation unit |

| ; | Falling pitch movement of intonation unit |

| . | Low falling pitch movement of intonation unit |

| <<p>> | Piano, soft |

| <<len>> | lento, slow |

| !AC!cent | Extract strong accent |

| ~ | Preparation of gesticulation |

| * | Holding of gesticulation |

| | | Boundary of gesture unit |

| ASSOC | Associative (-de) |

| CL | OveClassifier |

| COP | Copula verb (shi |

| CSC | Complex stative construction (de) |

| NOM | Nominalizer (de) |

| Q | Question (ma) |

| PRT | Particle |

| 3SG | Third person singular pronoun |