Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Multimodal Action Formation in Second Language Talk:

Japanese Speakers’ Use of the Gassho Gesture in English Apology Sequences

Tim Greer

Kobe University

Abstract

This study explores the multimodal action formation of second language (L2) apologies, particularly in relation to the members’ orientation to the significance of the misdemeanour. Although talk is the primary means through which participants accomplish apologies, embodied and paralinguistic interaction also play an integral role in conveying the proportional intensity of the apology. Members may bolster a second language apology with gestures from their first language, such as the Japanese gassho gesture. The study draws on conversation analytic research on L2 use as situated within a complex ecology of multimodal social interaction to reflect on the notions of interactional competence and interactional repertoires. The sequences were video-recorded among Japanese homestay visitors and their American host families.

Keywords: apologies, second language interaction, homestay interaction, multimodal conversation analysis, interactional repertoires

1. Introduction

Sacks once stated that ‘a culture is an apparatus for generating recognisable actions’ (1995, p. 226, original italics). Competent members of a group show themselves to hold that capacity by responding to others in an appropriate manner. Levinson (2013) terms such recognition as action ascription, which he specifies as ‘the assignment of an action to a turn as revealed by the response of a next speaker, which, if uncorrected in the following turn(s), becomes in some sense a joint ‘good enough’ understanding’ (p. 104). This fundamental notion within Conversation Analysis (CA) is used to establish an emic case for identifying a prior action formation: For example, if someone does an absolution, it is likely they just heard the prior speaker’s turn as an apology.

In general, people can be assumed to possess the necessary interactional competence to do this in at least one language, and in many cases they are able to extend it to other languages as well. It can be seen in our demonstrable access to the universal infrastructure of interaction, i.e. the way we use the apparatus of talk, such as turn-taking, repair and action formation. Interactional competence has been a core concern for CA researchers of second language (L2) talk (e.g. Hall & Pekarek Doehler, 2011; Markee, 2008; Young, 1999), and such research has significantly contributed to the study of second language use and acquisition.

However, Hall (2018) notes a tendency within the conversation analytic research to conflate the universal underpinnings of talk with specific learnables, and she therefore proposes a distinction between interactional competence and interactional repertoire, the latter of which she uses to refer to ‘objects of learning’, i.e. ‘the diverse semiotic resources for meaning-making comprising the L2 learners’ worlds’ (p. 33). The two are intended as complementary but separate concepts. A person’s interactional competence may be considered, for example, in terms of how they accomplish a request or a repair or a receipt, but their interactional repertoire would demonstrate the range of resources they have available to do that, including specific grammatical, lexical or phonological items, embodied practices and other semiotic resources. As a metaphor, the notion of repertoire also allows for the expansion of resources as they become available, just as a musician can increase their repertoire by hearing a new tune and practicing it. There may also be resources in one’s L1 repertoire that are reusable in the L2, either because they exist in both languages or because their usage is generally inferable (such as some gestures or non-lexical perturbations), and these can help support action ascription (Lilja & Piirainen-Marsh, 2019). It is also possible to conceive of elements of one’s passive repertoire, such as words that are understood but not yet part of a learner’s active vocabulary.

My analysis in this paper will build on the notions of interactional competence and interactional repertoire by considering action formation and ascription in apology sequences where at least one of the interactants is speaking English as a second language (L2), particularly in relation to bodily practices. I examine three extended apology sequences across four excerpts, each taking place in homestay settings in which a Japanese visitor is living with an American host family during a short-term study abroad tour. During these excerpts, the visitors rarely use their first language (L1), Japanese, since it is not spoken by their hosts, but they do incorporate particular emblematic gestures into their apologies that might be considered unusual in the language they are speaking (English). Using multimodal Conversation Analysis, I explore these apology sequences in relation to action formation and ascription (Levinson, 2013), and account for them with regard to the way members orient to the significance of the perceived misdemeanour. The analysis reveals how speakers format an apology through a mix of L2 (English) talk and L1 (Japanese) gestures, and that the participants do not treat this sort of semiotic assemblage as particularly problematic. After a brief review of recent CA literature on apologies and an overview of the dataset, I analyse several sequences of L2 apologies in detail, accounting for each from the publicly available perspective of the participants themselves.

2. Apologies in interaction

Investigations into the formulation of apologies are not rare within conversation analysis (Heritage & Raymond, 2016; Robinson, 2004; Schegloff, 2005) or in related fields such as pragmatics (e.g. Chang & Haugh, 2011; Blum-Kulka & Olshtain, 1984). However, such studies tend to focus primarily on talk-related aspects of how apologies are accomplished as action sequences or speech acts. Investigations that consider the entire interactional ecology of apology sequences are far less common, particularly in relation to second language (L2) interaction, even though much of the speaker’s stance is conveyed through embodied and paralinguistic means. There is therefore a need to address apologies as multimodal, jointly accomplished sequences of interaction and to account for spoken apologies as complex multimodal Gestalts (Mondada, 2014) or semiotic assemblages (Kusters, 2021; Pennycook, 2017). In doing so, we can begin to consider how formulaic expressions like ‘I’m sorry’ can be formed and regraded through co-occurrent embodiment, particularly among L2 users with limited access to the language they are using.

Apologies have long been of interest to second language researchers, particularly in relation to crosslinguistic influence (Hirama, 2011), interlanguage transfer (Flowers, 2018; Kasper & Ross, 1996) and the development of pragmatic competence (Chang, 2010). However, the vast majority of pragmatics research into apologies in L2 contexts has adopted etic methods, such as discourse completion tests (Bardovi-Harlig et al., 2008), rating-based surveys (Chang & Haugh, 2011) and role-play followed by retrospective verbal reports (Cohen & Ohshtain, 1985; Flowers, 2018; Olshtain & Cohen, 1983).

Even Kotani’s CA-based study of the way one Japanese participant uses ‘I’m sorry’ in an English conversation (Kotani, 2002) resorts to post facto informant interviews to bolster its observations on the naturally occurring interaction. What Kotani’s analysis does offer, however, is a detailed commentary on an extended apology sequence between an L1 speaker of English and an L2 Japanese speaker of English, taking into consideration how the Japanese speaker’s apology also contains elements of gratitude and indebtedness that may carry over from her first language. By documenting the sequential context, Kotani demonstrates that the Japanese speaker of English is likely to be translating the L1 Japanese expression ‘sumimasen’ as ‘I’m sorry’, and using it to express both gratitude (for the interlocutor’s extra work) and apology (for causing trouble), even though the English phrase only holds the illocutionary force of the latter.

Conversation analytic studies of L1 apologies have been far more prevalent. Robinson (2004) mapped out the sequential organization of explicit apologies in naturally occurring English, suggesting that they often occur as sequence-initiating actions (first-pair parts/FPPs), since participants are actively monitoring a given situation for possible (or ‘virtual’) offences (Goffman, 1971). Robinson notes that the act of apologizing orients to the perceived offence and a preference organisation exists in which a preferred second-pair part (SPP) response works to reject the apology.

The way an apology is formulated can also index the speaker’s perceived attitude toward the transgression. Heritage and Raymond (2016) suggest that explicit apologies are proportional to the offences they address: Minor offences get briefer apologies. A slip of the tongue might receive a quick ‘sorry’, while a broken vase would warrant a more expansive apology, perhaps including an explicit naming of the misdemeanour and an account (cf. Cirillo, et al., 2016). However, this proportionality does not always hold for larger offences, since relational and contextual contingencies can come into play when formulating the apology. Responsibility and culpability are therefore co-constructed through the format of the apology (Fatigante et al., 2016) and apology formulations can also be co-opted into the service of other actions, such as grabbing the floor (Park & Duey, 2020), enacting openings and closings (Galatolo et al., 2016), or restarting a just-prior performance (Ivaldi, 2016), which suggests that saying sorry should not always be taken as only doing an apology.

Heritage et al. (2019) later examine the broader sequence of action to clarify the relationship between an apology and the severity of the offence it addresses. They ‘make the case for regarding the ‘seriousness’ of a (virtual) offense or transgression as not so much an intrinsic property of the conduct itself (that is, the conduct that is being treated as an offense), but rather as an emergent property of the reflexive construction or format of the apology, and of the interaction with the apology recipient’ (p. 190). This recent work also addresses deontic aspects of apologies by accounting for the allocation of the interactants’ relative responsibilities and obligations within the sequence.

One aspect of apology sequences that remains under-addressed within CA, however, is their multimodal formulation. Much of the above CA research is based on audio-recorded phone conversations, and even when it uses video recordings of face-to-face interactions, the embodied aspects of the interaction are not often integrated deeply into the analysis. However, it is becoming increasingly recognised that interaction is assembled locally through a web of intermingled resources, or what Mondada (2014) calls a ‘complex multimodal Gestalt’ (p. 139). The spoken turn-construction of an apology can account partly for the speaker’s orientation to the offence, but their gaze direction will determine to whom they are directing the apology and a deep bow can upgrade its sincerity, just as a smirk or a casual wave might serve to downgrade it (see Hauser, 2019 on upgraded gestures in enactments of self-repair). These multimodal actions do not occur randomly, or in a manner that is divorced from the talk. As Mondada (2014) notes, ‘(t)he emergent construction of a complex multimodal Gestalt is done in response to the contingencies of the context and the interaction, adjusting to them and reflexively integrating them in building the progressivity of the action; thus, it is done by encountering and solving in real time practical problems encountered by the speaker and the co-participants’ (p. 142). If a gesture is designed to be interpreted in relation to the co-occurring talk, even an unfamiliar gesture can be interpretable.

To date, very few studies have focused on L2 embodiment during L1 apologies. One exception is a role-play study by Flowers (2018) that investigated backward transfer among 21 L1-English speakers who had lived in Japan. The aim was to determine whether features of Japanese apologies could be found in the participants’ English apologies on return to their native country. Flowers had the participants role-play a variety of situations to elicit apologies in English. She found that only two of them incoporated Japanese gestural elements, such as bowing or placing the palms together, into their L1 English apologies. In the current analysis, we will use multimodal CA to analyse transfer that involves the use of an L1 gesture within an L2 apology, something that has yet to be investigated in the literature. However, rather than framing it as transfer, a term which may hold monolingual connotations, we will consider it instead as a dynamic, creative social practice involving the flexible use of named languages, embodied practices and the interactional repertoires that surround them.

The aim of this paper, then, is to account for apologies and their orientations toward the gravity of the perceived misdemeanour in a multimodal manner. In particular, I will consider cases in which Japanese L2 speakers of English incorporate a particular Japanese gesture into an otherwise English apology. For want of a better word in English, I will term this a gassho gesture. As shown in Gifs 1-4, this gesture involves placing the palms of both hands together and positioning them at approximately chest height.

Gif 1

Gif 2

Gif 3

Gif 4

Although it looks similar to a prayer-like pose in many Western cultures, in Asian cultures this gesture has a broader range of meaning and is commonly deployed along with (or in place of) greetings, requests and appreciations, as well as apologies. To date there has been no conversation analytic research that has examined the deployment of the gassho gesture in relation to specific action sequences, but writing from a religious studies perspective, Maezumi and Glassman (1976) note the origins of the gesture are Buddhist and its most basic function is to express respect.

Even without access to the spoken interaction, these gifs give a sense of the range of ways the gassho gesture can be delivered, and hint at the possibility that faster deployment is more casual (Gifs 1 and 2) than cases where the gesture is held (Gifs 3 and 4). Other bodily bearings that can accompany the gesture include aversion of gaze and bowing of the head. Although it is unlikely that an L1 English speaker would use this gesture as part of an apology, its deployment by an L2 speaker would not necessarily detract from the speaker’s pragmatic aim. In fact, while it is not something they would normally do themselves, many English speakers would perhaps be able to recognise the gesture as an Asian one and possibly infer its meaning from the context. In other words, it may already exist as part of their passive repertoire of interactional practices.

3. Background to the data

The two conversations we will analyse originate from a dataset of Japanese novice1 speakers of English recorded at homestays in the United States. Excerpts 1 and 2 were recorded in Seattle in the summer of 2012. The homestay guest, ‘Shin’, was a first-year student from a Japanese university who was taking part in a 3-week study abroad program while living with a local host family which consisted of Mom, Dad and Gran. Excerpts 3 and 4 were recorded by Tai in his homestay in Honolulu in 2014. In that home there were four Japanese visitors aged 18 to 20 from two different universities living with the local hosts, who I will identify as Mom and Dad. The focal participants were asked to video-record instances of natural interaction between themselves and the host family. Written consent was obtained from all parties and the researcher was not present at the time of recording. The data are part of a larger corpus of study abroad interaction in which the visitors use and learn English while taking part in their host family’s daily routines. The full dataset consists of 56 recordings collected from 14 homestays in Australia and the USA between 2012 and 2019. Of that, nine recordings (3h 2min 30sec) were collected at Shin’s homestay and 12 recordings (2h 59min 35sec) at Tai’s.

Transcription was carried out according to Jeffersonian conventions (Jefferson, 2004) and embodied aspects of the talk are indicated in grey font below the talk tier. Following a simplified version of Mondada’s approach (Mondada, 2018), each tier is identified with the participant’s initial and a code indicating the locus of embodiment (e.g. -gz for gaze, -px for proximity, -bh for both hands, and so on). The onset of the embodied action is located relative to the talk tier via a vertical bar (|). See the appendix for further details.

4. Analysis

In this section I will analyse three apology sequences across four excerpts from the data. The first sequence involves a self-initiated apology and its subsequent downgraded reprise (Excerpts 1 and 2), the second explores an aborted bid for apology pursuit (Excerpt 3), and the third considers a case where an SPP apology is elicited via a complaint. Each includes a gassho gesture at some point, and a thick description of the broader sequence that surrounds them will account for the gassho gesture’s part in the multimodal action formulation.

We begin by examining two instances during a conversation between Shin and his host family.

Participants

Mom and Dad: Seattle homestay hosts

Shin: 19 year-old male Japanese guest on a 3-week study tour

Gran: Mom’s mother

Figure 1. The participant constellation

This conversation was recorded at the start of Shin’s second week in his homestay. Shin, Mom and Gran have been seated at the table for around a minute and Mom has been dishing up the meal. Dad comes to the table, sits, and drinks some water. Mom pats some oil off her pizza, but does not eat. Gran is seated facing forwards and Shin is eating. This family does not generally say grace (i.e. a pre-meal blessing), but for some reason in this instance Mom suggests they should. However, Shin initially fails to notice the family are praying, and instead continues to eat as normal. He later treats this as something worthy of an apology.

Excerpt 1. Sorry for eating

Gif 5

Gif 3

It is apparent from the recording that this is the first time during Shin’s visit the family has said a prayer before the meal, and it seems that Shin misses the preparatory cues that the family member use to physically align themselves for the beginning of the prayer. While Mom and Dad negotiate who will say the grace in lines 3 to 8, Shin is monitoring their activity, but also chewing and otherwise not visibly preparing himself to pray. It seems he does, however, notice that something is afoot when he mirrors Dad’s posture briefly in line 6, although he continues to look at Mom up until the first part of her prayer (line 11) before adopting the appropriate posture by closing his eyes and bowing his head. Shin has therefore committed at least two potential offences at this point – eating before the prayer and failing to align his physical stance to the start of the prayer – and it is the former that he orients to in his subsequent apology sequence.

Immediately after the amen in line 16 signals the closing of the prayer, Shin raises his head and puts his hands together in a gassho gesture (lines 17-18). In Japan this gesture is routinely used before eating (along with the phrase itadakimasu/ ‘I humbly receive’) to signal the opening of the meal (Suzuki, 2016). It is likely that this is how Shin initially deploys it, at least in line 18, as a sort of cultural equivalent to the formal opening that the family has just performed. Although he is probably unable to recite a Christian prayer2, Shin’s brief gassho gesture accomplishes a similar sequentially appropriate action, regardless of whether the family recognises or even notices it. This initial gassho is acknowledging the end of the prayer and is therefore also transitioning to the next topic.

At the end of line 18, Shin briefly touches his glass and continues to look down at the table for a moment, before reissuing the gassho gesture in line 19, as he apologises for eating prior to the prayer. The expanded apology is formulated as an ‘I'm sorry + named offence’ (Heritage & Raymond, 2016), which makes explicit the apologisable offence by distally locating it as a just-prior action. The gassho gesture is timed to coincide with Shin’s production of the word sorry, making its pragmatic force clear and differentiating it from the way he used it moments earlier (line 18) by inviting the recipients to assign the current co-occurrent action (an apology) to it. His laughed-through turn construction at this point might suggest to an English-speaking recipient that Shin is treating the misdemeanour as a minor matter, but laughter can also denote nervousness (Glenn, 2013) and it is likely that is at least part of the reason here. His hand-to-mouth gesture in line 19 serves to depict the word eating, but since it is deployed prior to the spoken version, it seems that Shin is using the gesture to arrive at the word he is searching for. Mom appears able to use the gesture to predict the word, delivering her response in overlap with Shin’s rather hesitant formulation.

Mom responds to Shin’s apology in line 22 with ‘Oh, no, that’s okay’, an oh-prefaced absolution (Robinson, 2004) which acknowledges that a possible misdemeanour has been committed, but works to claim that no offence has been taken. This therefore displays ‘the respondent’s understanding that the action of apologizing was in some way irrelevant or inappropriate’ (Robinson, 2004, p. 307). Within the same breath, Mom also delivers an account for her absolution (‘we do that, too’), which downplays the gravity of the misdemeanour by reworking the proterm (from an elided I to we) and implying that eating before the formal opening of the meal is not an offence. In the ongoing talk, the frequency of the family’s prayer briefly becomes a topic of conversation (not shown in the transcript but available on the video) before an assessment from Dad occasions a reprise of Shin’s apology, as shown in Excerpt 2.

Excerpt 2.

Open in a separate windowWhen apologising, Japanese speakers tend to initiate multiple rounds of sumimasen (‘I’m sorry’) (Kotani, 2002), and it seems this may be what Shin is doing here in English. After Mom admits that the family do not always say grace before eating (not shown), Dad produces a negative assessment of their negligence (line 48, ‘It’s dreadful but true’). Shin provides a news-marked receipt of Dad’s assessment (line 50, ‘I didn’t know that’), and the thread seems to be over with the 1.8-sec lapse in line 51. However, Shin’s ‘I didn’t know that’ is also hearable as an account for his transgression, suggesting Shin is still orienting to the apology, even though it seems the family members have moved on to other topics. It is at this point that Shin issues his second apology in first position, using the canonical form, ‘I’m sorry’ (line 52). It appears Shin is less concerned about the gravity of his offence this time though, as he continues to eat and look at his plate as he delivers the second apology. This suggests the formulation may be sensitive to the reprising and closing nature of Dad’s assessment (line 48), with Shin’s second apology also working to close down the sequence. In lines 54 and 55, Mom and Dad again reject the premise for Shin’s apology: Mom utters a non-lexical perturbation3 and shakes her head while Dad produces another oh-prefaced rejection followed by a diametrically opposed assessment to perform the absolution (‘That’s fine’), which Mom upgrades to ‘completely fine’ in line 57. Shin’s barely audible acknowledgement of this in line 58 again displays that he does not take this second iteration of his apology to be as serious as his first.

Access to two apology sequences from the same person on the same matter in relative succession affords us with opportunity to reflect microgenetically on how the participants are treating the seriousness of the offence. When Mom formulates an account for why the family does not always pray before eating (line 60), she and Shin both treat it as laughable and therefore further collaboratively accomplish the non-serious nature of Shin’s earlier misdemeanour. With this, rapport has been maintained, which is arguably the primary purpose of an apology. The absence of the gassho gesture in Shin’s second apology likewise suggests it is designed as less serious than his first. Heritage and Raymond (2016) posit a ‘principle of proportionality’ which they sum up with the maxim that ‘little virtual offenses get little apologies’ (p. 15). This maxim may be extended to include the non-lexical and embodied interaction that is co-produced with an apology. In Shin’s first apology, the hesitant delivery, his gaze shifts and his deployment of the gassho gesture all combine to display his orientation toward the gravity of the offence and therefore enact the sincerity of his apology. After the family members have forgiven him and implicated themselves in the same offence, his second apology is much lighter, as evidenced partly through its embodied delivery. Therefore, the way the action is locally adjusted to its sequential environment can provide socially available clues to the speaker’s changing stance toward the misdemeanour.

In Excerpts 3 and 4, we are again fortunate to have access to two successive apologies involving the same participant (another Japanese homestay guest, Tai, with a different host family). However, in this case the first apology is treated as a proportionally minor offence (committed by two other guests, Sho and Gen) that Tai seems to be about to pursue. Just as that happens though, he finds himself at the centre of another incident that demands a bigger apology. This data was collected in a homestay in Hawaii that included two host parents and four Japanese guests from two different universities, as outlined in Figures 2 and 3.

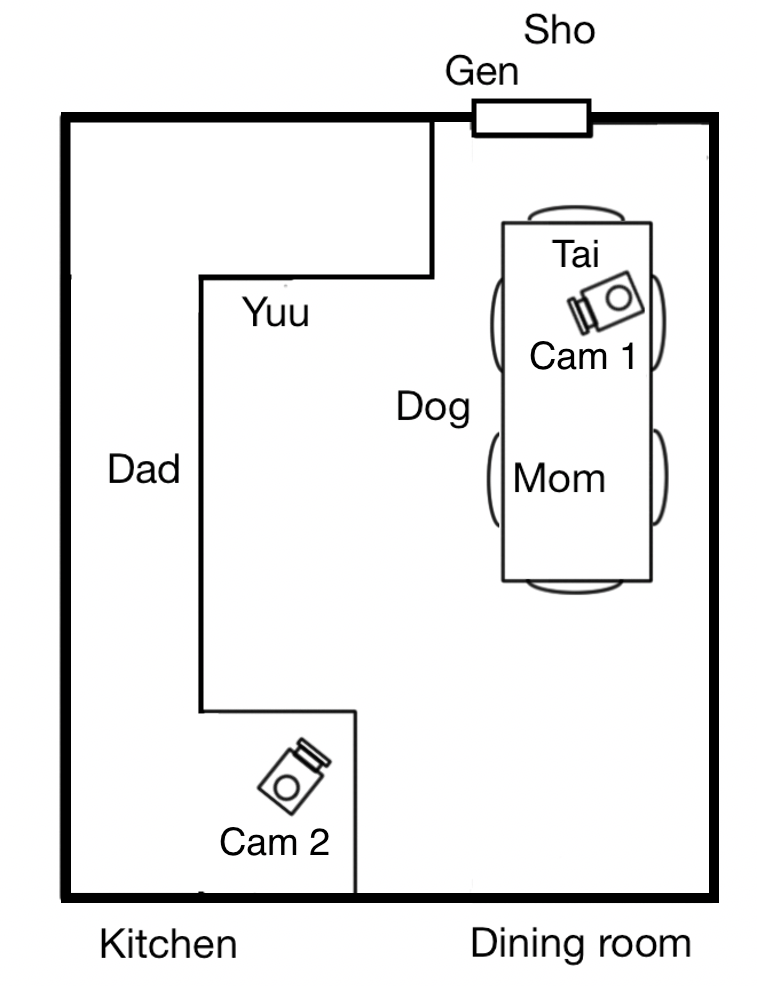

Figure 2. The participant constellation in Excerpts 3 and 4

Figure 3. A schematic of the room

Gen and Sho enter at the start of the excerpt. The table on the camera (Cam1) catches Mom and part of the kitchen. The camera on the kitchen counter (Cam2) is directed at Tai and Mom, who are seated at the table.

Participants

Mom and Dad: Hawaiian homestay hosts

Yuu and Tai: 19 year-old male Japanese homestay guests on a 3-week study tour from University A

Gen and Sho: (late teen/early twenties) male Japanese homestay guests on a 4-week study tour from University B

Dog: Mom and Dad’s pet, a large dog

It is, as Mom puts it, a ‘leftover meal’ and everyone is fixing their own dinner. Mom and Tai are already eating, and Yuu and Dad are in the kitchen preparing their meals. The dog barks, and Gen and Sho walk in late. In the prior talk, their absence has been the topic of discussion between Mom and Tai, with Tai reporting that he saw them on the same bus he was on although they didn’t get off with him at the regular stop. Our initial analysis will focus on the relative levity of Gen’s apology and how Tai subsequently holds Gen and Sho (as a party) accountable for further explanation and thereby makes a bid to upgrade the gravity of the offence.

Excerpt 3.

Gif 2

Mom greets Sho and Gen as they walk in (line 2) and there is nothing in her tone of voice that seems upset. Even so, Gen formulates his response as an unexpanded, ‘bare’ apology (line 3, ‘sorry’), which Heritage and Raymond (2016) typify as ‘the most minimal apology format’ (p. 7), usually deployed to deal with minor interactional issues such as self-initiated self-repair or open-class repair initiations. In this case, however, the offence might arguably call for a more expanded apology, such as one that named the offence and specified the agent (‘I’m sorry for being late’), and we will see that Tai at least treats the apology as inadequate in later talk (lines 8-13). It could be that this sort of apology is beyond Gen’s interactional competence, and the consequent repetitions of ‘sorry, sorry’ in line 5 are his way of upgrading it while maintaining the progressivity of the talk with the limited linguistic resources available to him. He also achieves some semblance of gravity by prioritising the apology as the first thing he does on entering, even beyond responding to Mom’s greeting (line 2) or Tai’s minimal Japanese greeting (line 4). That said, Gen’s embodied action depicts the apology as non-serious: In line 5, he keeps walking as he utters the apology, and his gassho gesture is brief and casual, delivered with a smile and followed by a flopped release of his arms (Gif 2). This multimodal Gestalt of actions suggests that Gen and Sho do not view their tardiness as any great problem, and in line 6 Mom’s SPP preferred absolution (Robinson, 2004) implies that she aligns with their formulation. His bodily practices therefore play an integral role in expressing his attitude toward the misdemeanour and in making that recognisable to the recipients.

Tai, on the other hand, adopts a rather different stance. During the gap of silence in line 7, he glances from Gen to Sho and then back to Gen. By not self-selecting at this point, Tai displays an orientation toward further incipient talk from either Gen or Sho, but when such a contribution is not forthcoming after roughly a second, he initiates the account that he evidently views as a sequentially due part of the apology (line 7, ‘but where were you?’). Heritage and Raymond (2016) hypothesise that ‘apologies which include both a naming (or indexing) of the offense and an account of how the offense came to pass are a larger and more protracted form of apology, more likely to be addressed to distal apologies and possibly more major offenses’ (p. 13). Even though Mom and the others do not treat it that way, it seems that this is the sort of apology for which Tai is holding Sho and Gen accountable. In the next turn, Sho produces an open-class repair initiator (line 10, ‘huh?’), perhaps suggesting some deontic incongruence (Stevanovic & Peräkylä, 2012), in which Sho is resisting Tai’s authority to determine the form of his apology, and therefore the proportionality of the offence. Tai’s post-expansive formulation is also hearable as an accusatory question (Heritage, 1998), which again may be at odds with his right to ask it: Tai is a recently arrived guest from a different school, while Gen and Sho have lived with the family for longer and are more familiar with their routines and expectations. At the very least, Tai is a guest rather than part of the host family, and so his right to an apology could be disputed, especially given that Mom, as the host, has not treated the offence as a serious one. In response to Sho’s repair initiation, in line 11 Tai repeats the account initiation, this time in a laughed-through manner and while holding both palms up, accentuating the interrogative nature of the turn. Sho’s response in line 13 (‘I was only in Costco’) uses ‘only’ as a softener (Edwards, 2000) to downplay the seriousness of the offence and he appears to be going on to explain further in line 18. However, before that can happen, the tables turn and another offence that might be relatively minor is treated as proportionally larger: Tai has used the wrong utensil for dishing out ham.

Excerpt 4.

Gif 4

Gif 6

This sequence actually begins back in line 14 when Dad can be heard laughing off-camera, presumably at the moment he discovered someone has used an iced tea spoon for serving ham. The details of how the spoon has been used on the ham are not obvious from the video, but what is clear is that Dad finds this unusual, amusing and possibly inconvenient in some way. His laughter and subsequent overlapped inquiry (line 19) commandeer the floor, and Tai’s earlier line of questioning (Excerpt 3) is immediately abandoned. Like Tai’s question to Sho, Dad’s ‘Who used this for the ham?’ (line 22) has an accusatory tone and therefore constitutes a possibly apology-implicative FPP. Interestingly, Dad does three iterations of his question before it comes to completion (lines 19, 21 and 22) and each makes it clearer that he is aware that Tai is the culprit. As mentioned earlier, line 19 is in overlap, so it could be that Dad dropped out and restarted his turn in the clear at that point in order to establish maximal recipiency. It is also the case that Dad has not been active in the conversation up until this point, neither acknowledging Gen and Sho’s entrance nor participating in the discussion of their prior whereabouts. Therefore, Dad’s turn in line 19 marks his entry into the conversation and does so by changing the topic without any particular transitional discourse marker. This may help shape its turn design as one which adopts a negative or accusatory stance, and indeed the recipients hear it that way by abandoning the earlier thread of talk.

Even in his first iteration of ‘Who used this?’ (line 19), Dad is already orienting to Tai by shifting his gaze toward him, but his restart is undoubtedly also a means of gaining reciprocal gaze from Tai (Goodwin, 1981). During the second iteration of the question (line 21), Tai looks to Dad as Dad holds up the spoon in an embodied specification of the deictic ‘this’. Dad’s gaze shift simultaneously constitutes a projected answer to the question. The culprit cannot be Gen or Sho, who have just walked in, and it is unlikely to have been Yuu, who is standing near the refrigerator and yet to dish out his meal. The only people who are currently eating are Mom and Tai, and it appears that Dad has eliminated Mom from his list of suspects (see Goodwin, 1981 on designing talk for different types of recipients). It is at this point that Tai also appears to acknowledge his guilt, uttering a change-of-state noticing (line 23, ‘oh’) and raising both hands into the air and holding them there in a prolonged display of shock (line 24). This makes public his awareness of the offence and an apology becomes conditionally relevant in the ongoing talk.

In lines 26 to 30 there is an insertion sequence as Mom torques her torso to see what Dad’s ‘this’ refers to. She initiates other-repair and Dad specifies the utensil as ‘our iced tea spoon’ (line 28), to which Mom aligns with a shocked receipt (‘oh my god’, line 30). This sets up a shared stance that positions her in the same party as the offence-taker, Dad. Tai reissues his oh-token as a non-lexical interjection (‘aargh’, line 31) and follows it with a somewhat hyperbolic embodied display of apology (line 32), putting his hands to his head and closing his eyes, then turning to Dad and doing an ultra-formal version of the gassho gesture with both hands held high in front of his face (line 32). He holds this pose as he utters ‘I’m so sorry’ (line 33), then combines the gesture with a bow and holds the gassho until the end of line 38. In other words, the way Tai designs his embodied behaviour calibrates the proportionality of his offence, orienting to it as something more serious than Sho and Gen’s tardiness that was the topic of the prior talk (Excerpt 3). The spoken format of the apology is equally formal, including an expression of agency (subject and copula) as well as the modifier ‘so’ that amplifies the extent of the speaker’s regret (Fatigante et al, 2016). Tai’s prolonged gestural hold between lines 33 and 38 suggest that the response that it initiates (Dad’s absolution) is still pending (Cibulka, 2015).

The fact that Dad does not provide immediate absolution may contribute to Tai’s ongoing display of remorse. Unlike in other examples we have examined, Dad instead responds by upgrading his complaint, albeit in a fairly light-hearted manner designed to extend the laughter, and perhaps thereby defuse the tension. He deploys the address term ‘bruh’ pre-positionally in line 34 to adopt a mock-antagonistic stance (c.f. ‘mate’; Rendle-Short, 2010) and follows this with a laughed complaint (line 24) which protracts the sequence by not accepting the apology. In line 44, Tai then upgrades his display of remorse by producing a self-directed expletive while averting his gaze and rubbing his temples. This seems to serve a similar function to a self-deprecation (Pomerantz, 1984), but rather than occasioning disagreement, in this case it leads Mom to provide the absolution in Dad’s stead (lines 46-48), suggesting again that they are participating in the talk as a couple at this point. This leads Dad to provide an absolution of his own (‘it’s okay’, line 49), but he immediately qualifies it by revisiting the offence (‘it’s just not an appropriate one for ... picking up ham’, lines 49 and 54). Dad’s qualification has an instructional tone to it, and he accompanies it with a timely displaying of picking up a slice of ham with a fork. After the first part of Dad’s turn, Tai lets out an audible sigh and slumps in his chair, in yet another embodied display of remorse. The laughter throughout the sequence is clearly directed at Tai, and Mom’s coda-like commentary on Tai’s stance in line 57 (‘He was like, “oh my god”’) provides a slot in lines 58-59 where Tai can co-opt her turn as a substrate (‘Yeah, yeah that’s right. I wanna say it to myself, “oh my god”’) and therefore finally laugh along with the others (line 62). Mom’s noticing here focuses on the gesture that is commonsensically more readable to her: the hands-to-the-head ‘oh my god’ gesture. She does not mention the gassho gesture specifically, but that is not to say that she did not recognise it as responsive to Dad’s accusation.

Across the examples, we can see that the gassho gesture is calibrated to the seriousness of the apology, and also helps to treat it as such. In Excerpts 1 and 2, the speaker is apologising for the same transgression, but his second version does not use a gassho gesture. In Excerpt 3, the transgressor issues a relatively light apology in the first position: The gassho gesture is produced quickly while Gen is walking in and the apology is not specified or addressed to anyone in particular, which Tai treats as inadequate by initiating an account. Finally, Excerpt 4 is dealt with as a much more serious offence, since it is occasioned by the offended party’s (Dad’s) complaint-implicative noticing and therefore issued in second position. The transgressor (Tai) also acknowledges the proportionally severe nature of the offence by holding his gassho gesture well past the apology and ‘doing being lost for words’. The jointly achieved formulation of the apology sequence reflexively dictates the relative severity of the offence, and the participants’ stance towards it. The shape and timing of the gassho gesture is a salient component of the action accomplishment, contributing to the way that the apology is interpreted by the recipients.

5. Concluding discussion

This analysis has built on CA research into apology sequences (1) by applying findings from L1 talk to situations where speakers are using a second language (or dealing with someone else who is), and (2) by paying attention not only to the vocal-aural (spoken) modality, but also to the co-occurrent visuospatial modalities (Enfield, 2005) that help shape the nature and extent of an apology. In doing so, we are able to arrive at a richer understanding of how apologies are jointly accomplished in face-to-face interaction, particularly in intercultural settings like these short-term homestays, where damage to rapport can have serious consequences for the on-going success of the visit.

In considering embodiment as an element of action formation, we have seen that the Japanese guests design their English apologies by delivering them along with an emblematic gesture that would make perfect sense in their first language (Japanese). This means that the gesture is primarily culture-specific and the guests hold the moral rights to it. At times it can precede the apology proper (e.g. Excerpt 4, line 32), suggesting that it can be used to convey meaning without words. Whether or not the host families fully recognise the gassho gesture, the fact that it accompanies an apology allows for the possibility that they will commonsensibly view it in as part of that action. Since the hosts do not treat it as problematic in any way (e.g. by initiating repair on it), the guests are at least within their rights to believe the English-speaking hosts are able to gloss the gesture’s meaning from the context. The result is a semiotic assemblage that consists of an L1 gesture and L2 talk, akin to what has been termed translanguaging (Li, 2018).

It is certainly also possible to do an apology without the gesture, or a range of other embodied actions, so it would seem that it serves in part to calibrate the pragmatic action, upgrading or downgrading the apology and therefore specifying the severity of the offence and indexing the speaker’s sincerity. This suggests an embodied layer to Heritage and Raymond’s (2016) observation that apologies are proportional to the offences they address. When Gen comes home late (Excerpt 3), the casual stance of his ‘sorry’ is at least partly accomplished by the fact that his gassho gesture is brief, languid and done ‘on the fly’ while walking into the room. In contrast, Tai’s apology just moments later (Excerpt 4) features a long-held gassho gesture that is delivered in stand-alone form both before and after the spoken ‘I’m sorry’, and holding it for longer formats the action as upgraded. Together, this lamination of talk and embodiment calibrate the action formation, and this becomes evident in how the recipients treat it.

The gassho gesture is just one element of a complex multimodal Gestalt, that includes the speaker’s gaze direction, the expression on their face, their tone of voice and other embodied features of the participants’ talk. These should also be taken into account as part of determining the nature of an apology and the offence it indexes. The apology likely affords the host family insight into the meaning and usage of the gesture, and therefore it could be that the host family members are learning along with the visitors, suggesting that interactional competence can involve joint-development in study abroad contexts (Greer, 2019).

While it seems clear that the gassho gesture is an important part of the guests’ interactional repertoire for apologising, it is probable that it is not something that the hosts do in the same situation. Predictably, there was no instance in the data when the hosts used the gassho gesture in an apology. But the fact that they did not treat it as remarkable when the guests did it suggests that they were probably aware of its existence, just as they are also likely to know that Japanese people bow during greetings. The gassho gesture can be seen in movies and the like, and it would be unsurprising for it to be in the hosts’ passive interactional repertoire. In other words, they recognise it but do not actively use it themselves, just as Shin can realise a prayer has started or Tai reacts to Dad’s use of ‘Bruh!’ as some sort of admonishment. These are interactional practices that are comprehensible but not yet part of the recipient’s active repertoire. Given the moral and deontic rights that are associated with them, it may be that such practices may never become so, but the way they are treated at least shows they are unproblematic within the interactional context. An interactional repertoire, therefore, is an expanding repertoire that incorporates linguistic, gestural and other semiotic resources and need not be limited to traditional boundaries of named languages. Action formation among multilingual interactants can draw from a range of interactional repertoires.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part through JSPS Grant-in-Aid No. 2450619. I would like to thank Søren Eskildsen and Rue Burch for their comments on earlier versions of this paper.

References

Bardovi-Harlig, K., Rose, M., & Nickels, E. L. (2008). The use of conventional expressions of thanking, apologizing, and refusing. In M. Bowles, R. Foote, S. Perpiñán, & R. Bhatt (Eds.). Selected proceedings of the 2007 second language research forum (pp. 113-130). Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Blum-Kulka, S., & Olshtain, E. (1984). Requests and apologies: A cross-cultural study of speech act realization patterns (CCSARP). Applied Linguistics, 5(3), 196-213. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/5.3.196

Chang, Y. F. (2010). ‘I no say you say is boring’: The development of pragmatic competence in L2 apology. Language Sciences, 32(3), 408-424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2009.07.002

Chang, W. L. M., & Haugh, M. (2011). Evaluations of im/politeness of an intercultural apology. Intercultural Pragmatics, 8(3), 411-442. https://doi.org/10.1515/iprg.2011.019

Cibulka, P. (2015). When the hands do not go home: A micro-study of the role of gesture phases in sequence suspension and closure. Discourse Studies, 17(1), 3-24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445614557756

Cohen, A. D., & Olshtain, E. (1985). Comparing apologies across languages. In K. R. Jankowsky (Ed.), Scientific and humanistic dimensions of language (pp. 175-184). John Benjamins.

Cirillo, L., Colón de Carvajal, I., & Ticca, A. C. (2016). “I'm sorry + naming the offense”: A format for apologizing. Discourse Processes, 53(1-2), 83-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853x.2015.1056691

Dings, A. (2012). Native speaker/nonnative speaker interaction and orientation to novice/expert identity. Journal of Pragmatics, 44(11), 1503-1518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.06.015

Edwards, D. (2000). Extreme case formulations: Softeners, investment, and doing nonliteral. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 33(4), 347-373. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327973rlsi3304_01

Enfield, N. (2005). The body as a cognitive artifact in kinship representations: Hand gesture diagrams by speakers of Lao. Current Anthropology, 46(1), 51–81. https://doi.org/10.1086/425661

Fatigante, M., Biassoni, F., Marazzini, F., & Diadori, P. (2016). Responsibility and culpability in apologies: Distinctive uses of “sorry” versus “I'm sorry” in apologizing. Discourse Processes, 53(1-2), 26-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853x.2015.1056696

Flowers, C. (2018). Backward transfer of apology strategies from Japanese to English: Do English L1 speakers use Japanese-style apologies when speaking English? Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University.

Galatolo, R., Ursi, B., & Bongelli, R. (2016). Parasitic apologies. Discourse Processes, 53(1-2), 97-113. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853x.2015.1056694

Glenn, P. (2013). Interviewees volunteered laughter in employment interviews: A Case of “nervous” laughter? In P. Glenn, & E. Holt (Eds.), Studies of laughter in interaction (pp. 255-275). Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.1086/222003

Goffman, E. (1971). Relations in public: Microstudies of the public order. Basic Books.

Goodwin, C. (1981). Conversational organization: Interaction between speakers and hearers. Academic Press.

Greer, T. (2018). Learning to say grace. Social Interaction: Video-bases Studies of Human Sociality 1(1). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7146/si.v1i1.105499

Greer, T. (2019) Initiating and delivering news-of-the-day tellings: Interactional competence as joint development. Journal of Pragmatics. 146, 150-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2018.08.019

Hall, J. K. (2018). From L2 interactional competence to L2 interactional repertoires: Reconceptualising the objects of L2 learning. Classroom Discourse, 9(1), 25-39. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2018.1433050

Hall, J. K., & Pekerak Doehler, S. (2011). L2 Interactional Competence and Development. In J. K. Hall, J. Hellermann & S. Pekarak Doehler (Eds.). L2 interactional competence and development, (pp. 1–15). Multilingual Matters.

Hauser, E. (2019). Upgraded self-repeated gestures in Japanese interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 150, 180-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2018.04.004

Heritage, J. (1998). Oh-prefaced responses to inquiry. Language in Society, 27(3), 291-334. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404500019990

Heritage, J. (2002). Oh-prefaced responses to assessments: A method of modifying agreement/disagreement. In C. Ford, B. Fox, & S. A. Thompson (Eds.), The language of turn and sequence (pp. 196–224). Oxford University Press.

Heritage, J., & Raymond, C. W. (2016). Are explicit apologies proportional to the offenses they address?. Discourse Processes, 53(1-2), 5-25.

Heritage, J., Raymond, C. W., & Drew, P. (2019). Constructing apologies: Reflexive relationships between apologies and offenses. Journal of Pragmatics, 142, 185-200. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853x.2015.1056695

Hirama, K. (2011). Crosslinguistic influence on pragmatics: The case of apologies by Japanese-first-language learners of English. McGill University (Canada).

Ivaldi, A. (2016). Students’ and teachers’ orientation to learning and performing in music conservatoire lesson interactions. Psychology of Music, 44(2), 202-218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735614562226

Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcription symbols with an introduction. In G. Lerner. (Ed.) Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 13–31). John Benjamins.

Kasper, G., & Ross, S. (1996). Transfer and proficiency in interlanguage apologizing. In S. Gass, & J. Neu (Eds.). Speech acts across cultures: Challenges to communication in a second language (pp. 155-187). Mouton de Gruytor.

Kotani, M. (2002). Expressing gratitude and indebtedness: Japanese speakers' use of "I'm sorry" in English conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 35(1), 39-72. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327973rlsi35-1_2

Kusters, A. (2021). Introduction: the semiotic repertoire: Assemblages and evaluation of resources. International Journal of Multilingualism, 18(2), 183-189. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2021.1898616

Levinson, S. C. (2013). Action formation and ascription. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.). The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 103-130). Wiley-Blackwell.

Li, W. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 9-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2019.1657275

Maezumi, H. T., & Glassman, B. T. (Eds.). (1976). On Zen practice. Wisdom Publications. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.04.004

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85-106. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2017.1315810

Park, I., & Duey, M. (2020). I’m sorry (to interrupt): The use of explicit apology in turn-taking. Applied Linguistics Review, 11(3), 377-401. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2018-0017

Pomerantz, A. (1984). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shaped. In Atkinson, J. & Heritage, J. (Eds.). Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 57-101). Cambridge University Press.

Rendle-Short, J. (2010). ‘Mate’ as a term of address in ordinary interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(5), 1201-1218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.09.013

Robinson, J. D. (2004). The sequential organization of "explicit" apologies in naturally occurring English. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 37(3), 291-330. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327973rlsi3703_2

Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures on conversation, Vol I & II. Blackwell.

Schegloff, E. A. (2005). On complainability. Social problems, 52(4), 449-476. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.699260

Suzuki, M. (2016, September 20). The meaning of itadakimasu and how it reduces food waste. Tofugu. https://www.tofugu.com/japanese/itadakimasu-meaning/

Wagner, J. (2018). Multilingual and multimodal interaction. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 9-30. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx058

Young, R. (1999). Sociolinguistic approaches to SLA. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 19. 105–132. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0267190599190068

1 By novice, I mean that the guests are relative novice speakers of English compared to the hosts. In other words, this is an emic definition that is based on the participants’ own orientations at various points throughout the dataset (Dings, 2012). ↩

2 Compare this with Greer (2018), in which another homestay participant learned to say grace over the three-week period. ↩

3 Mom’s turn here is two pressed /n/ sounds that are hearable as a truncated form of the word no. They are not, however, a simple cut-off, and she produces one of the sounds in a relatively animated tone that suggests surprise at the apology and the other with falling intonation that accomplishes the rejection proper. ↩

Appendix

Transcription conventions

The transcripts follow standard Jeffersonian conventions (Jefferson, 2004), with embodied elements shown via a modified version of the conventions developed by Mondada (2018). The embodied elements are positioned in a series of tiers relative to the talk and rendered in grey.

| | Descriptions of embodied actions are delimited between vertical bars

|---> The action described continues across subsequent lines

---->| The action reaches its conclusion

>> The action commences prior to the excerpt

--->> The action continues after the excerpt

..... Preparation of the action

---- The apex of the action is reached and maintained

,,,,, Retraction of the action

~~~~ The action moves or transforms in some way.

SHIN The current speaker is identified with capital letters

Participants carrying out embodied action are identified relative to the talk by their initial in lower case in another tier, along with one of the following codes for the action:

-gz gaze

-lh left hand

-rh right hand

-bh both hands

-px proximity

-hd head

-gs gesture

Frame grabs are positioned within the transcript relative to the moment at which they were taken.