Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Embodied Micro-Transitions:

A Single-Case Analysis of an Amateur Band Studio Session

Junichi Yagi

University of Hawai'i

Abstract

Employing multimodal conversation analysis, this article examines a single episode of interaction taken from a studio session, during which two musicians check a chord progression. It illustrates how intra-activity micro-transitions are solely achieved through embodied actions. The detailed analysis reveals (a) how the suspension of “playing-along” is occasioned to exhibit participants’ orientation to auditory objects whose “turning-on” makes relevant disengagement from other interactional involvements; and (b) how the temporal complexities of multiactivity are contingently managed in exclusive order, explicating (c) members’ embodied practices for working around the organizational constraints of the auditory objects.

Keywords: activity transitions, auditory objects, multiactivity, temporality, music

1. Activity transitions in performance-based settings

As a sociological discipline, Conversation Analysis (CA) has long kept an interest in the systematic management of transitions from one activity phase to another (Deppermann et al., 2010; Robinson & Stivers, 2001); most notably, openings and closings in telephone conversations (Schegloff, 1968; Schegloff & Sacks, 1973). Certainly, its analytic interest goes beyond the transitions in ordinary conversations. As shown by past literature, interaction in institutional settings is “pre-organized” (Robinson, 2013, p. 258) as multiple phases embedded within a single larger activity (Heritage & Clayman, 2010).1 Such “pre-organizedness” arguably makes institutional interaction a perspicuous locus to probe activity transitions. Research on institutional interaction has indeed shown various ways in which activity transitions can be contingently managed in a stepwise manner (Deppermann et al., 2010) through embodied and material resources (Burch & Kasper, 2021; Nevile et al., 2014).

Kushida et al. (2017) defined the overall structural organization (Robinson, 2013) as a normative organization of phases that should occur within a specific activity, and as a set of systematic procedures through which participants manage, and negotiate, recognizable boundaries between these phases.2 In this view, each phase is normatively expected to unfold step by step—regardless of the actual sequential trajectory. This does not mean, however, that smaller micro-activities cannot be managed simultaneously (Haddington et al., 2014).3 Research on multiactivity, both in mundane and institutional situations, has shown how these micro-activities can unfold in various temporal orders (Mondada, 2014). Such multi-layered structure reveals tacit, yet powerful, organizational constraints (Rauniomaa & Heinemann, 2014). The point is, understanding when, and how, to display understanding of boundaries between activities is participants’ practical task—be it in mundane conversations (Hayashi & Yoon, 2009), institutional talk (Mikkola & Lehtinen, 2014; Robinson & Stivers, 2001), or instructional settings in music (Reed & Szczepek Reed, 2013) and sports (Råman, 2018).

Building on ethnomethodological (EM) and conversation-analytic (CA) literature on activity transitions in performance-based settings,4 this article presents a single case analysis of intra-activity micro-transitions, solely achieved through embodied actions. Specifically, I analyze a single episode of interaction taken from a band studio session, during which two musicians check a chord progression. In the studio session, the activity of “chord-checking” consists of two recognizable micro-activities: (a) “listening” and (b) “playing-along.”5 In my data, the participants first agree to listen, using an iPod, to the album version of a song they are practicing, as it turns out that the bassist does not know the chords of the pre-chorus. They then start playing their instruments along with the music coming from the surrounding audio speakers. When the song reaches the target segment (i.e., pre-chorus), the playing-along is suspended midway, with the bassist re-orienting his entire body to an adjacent audio speaker. The suspension exhibits (a) the participants’ “increased involvement” (Heinemann & Rauniomaa, 2016, p. 6) with another activity (“listening”) made relevant anew, and (b) an embodied orientation to auditory objects, i.e., “devices that produce sounds when in use” (Rauniomaa & Heinemann, 2014, p. 145). In other words, the audibility of the external music output source is momentarily prioritized over the commitment to the activity-in-progress, “playing-along,” which is locally constructed as “disruptive” to another involvement, “listening” (Heinemann & Rauniomaa, 2016).

However, this is not without negotiation—in this case, an entirely embodied one. My analysis first demonstrates (a) that micro-transitions embedded within a single activity can be achieved solely through embodied actions. It also reveals (b) how the suspension of “playing-along” is occasioned to exhibit participants’ embodied orientation to auditory objects, whose “turning-on” makes relevant disengagement from other interactional involvements. Finally, it accounts for (c) how the temporal complexities of multiactivity are contingently managed in exclusive order (Mondada, 2014) by explicating (d) members’ embodied practices for working around the organizational constraints of the auditory objects.

2. Projection in activity transitions

Projection plays a key role in activity transitions. According to Stukenbrock (2018), in face-to-face interaction, projection unfolds as a multimodal phenomenon, which cumulatively emerges within a “multimodal compaction zone” (Stukenbrock, 2018, p. 40), so as to achieve the “highest informational value” (p. 40). She proposed four sub-steps between the first pair part (FPP) and the second pair part (SPP) of an adjacency pair (instruction → instructed action): (a) deictic summons for gaze, (b) answer by gaze allocation, (c) monitoring the gaze, and (d-1) continuation with SPP, or (d-2) repair after gaze monitoring (Stukenbrock, 2018, p. 62). This visual-analytic procedure is embedded within turns to secure the witnessability (Nevile, 2007) of an instructing action in the “shared visual field” (Nishizaka, 2000, p. 108). For instance, launching a correction sequence during basketball practice requires specific spatial configurations of the multiple bodies on the move (Evans & Lindwall, 2020). In order to initiate a correction, the coach first needs to suspend the activity-in-progress (“drill”) to project the initiation of a new activity. The coach achieves this correction-projection “through his talk and whistle blow” (Evans & Reynolds, 2016, p. 535), and by “repositioning himself close to the players” (Evans & Reynolds, 2016, p. 535), which is designed to maximize the witnessability of the forthcoming embodied demonstration (Råman, 2018).

Although activity transitions in performance-based settings are overwhelmingly dynamic, multimodal accomplishments, language also plays an important role. In dance lessons, teachers often use linguistic expressions, such as “let’s try” and “one more time” (Broth & Keevallik, 2014, p. 113). Broth and Keevallik (2014) termed these expressions “practice projectors” (p. 112), a useful resource for both participants and the analyst. A similar linguistic resource is identified in martial arts training, which Råman (2018) modified to “teaching projectors” (p. 12). In vocal masterclasses, two types of directives, “local directives” and “restart-relevant directives,” are used to manage performance restarts (Szczepek Reed et al., 2013, p. 36–42). Although some scholars adopting phenomenological approaches may not fully endorse it (Meyer et al., 2017), the division of labor between language and the body is a rapidly growing topic within interactional research (Keevallik, 2018). The current article aims to contribute to this research area by examining micro-transitions solely achieved through embodied actions.

Just as in many other institutional settings, in which multiple phases are embedded within a single larger activity, activity transitions in performance-based settings expectedly unfold step by step (Deppermann et al., 2010), and in achieving this incremental unfolding, projection is essential (Stukenbrock, 2018). Participants laminate various resources, including talk, embodiment, objects, and space (Goodwin, 2018), to manage entrances into, and exits from, performance (Råman, 2018; Reed & Szczepek Reed, 2013). These local complexities demand that participants distribute their orientations (Nishizaka, 2008) to address different recipients and/or activities simultaneously (Deppermann et al., 2010), and this double orientation has been found to be crucial in closing the current activity phase and moving onto another (Robinson & Stivers, 2001). A lack of such organizational flexibility would hinder smooth transitions, disabling us to engage in mundane activities as competent members (Garfinkel, 1967). With this, I turn to a commonsense observation that multiple activities can be, and are, organized simultaneously, within and across turns/sequences (Haddington et al., 2014).

3. Multiactivity and auditory objects

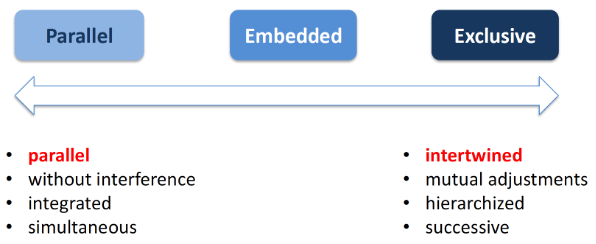

According to Mondada (2014), multiactivity—an inseparable element of our everyday life (Haddington et al., 2014)—is characterized by three temporal orders: (a) parallel order, (b) embedded order, and (c) exclusive order (p. 35). As shown in Figure 1, these are not entirely separate categories, but should be seen as situated on a conceptual scale.

Figure 1. Three temporal orders of multiactivity

In parallel order, multiple activities are achieved “without any hitches or interferences” (Mondada, 2014, p. 47), running simultaneously in a smooth, unproblematic way. The second embedded order is characterized by “constant mutual adjustments” (Mondada, 2014, p. 50). With multiple involvements, each participant needs to adjust their speech and course of action carefully, speeding up and slowing down, so that they can complete the ongoing unit together. These adjustments can be minimal, with relatively small perturbations, but occasionally, “successive alternations within turns” (Mondada, 2014, p. 52), or “within the sequence” (Mondada, 2014, p. 55), are required. Put differently, as one moves along the scale to the right (Figure 1), the temporal organization increasingly demands that one activity be prioritized over another, causing more successive transitions.

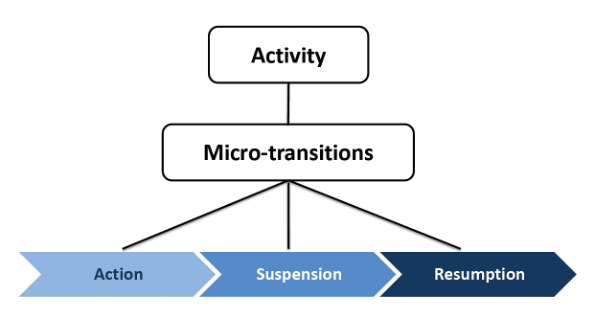

Particularly relevant to my analytic focus is the third exclusive order. When the simultaneous management of multiple activities becomes difficult, participants occasionally abandon one or more courses of action in favor of a single exclusive course of action. This means that, within a single larger activity, there are small successive transitions between (a) the ongoing course of action, (b) suspension, and (c) resumption. In this article, I call these small intra-activity transitions micro-transitions (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Exclusive order within micro-transitions

Accordingly, I adopt the term micro-activities in referring to the small activities embedded within a single larger activity. There are a few reasons for this terminological decision. First, the overall activity examined (“chord-checking”) is much shorter in its length than those typically studied in CA (Deppermann et al., 2010; Robinson & Stivers, 2001). Second, the smaller activities embedded therein lack clear boundaries between “opening” (Schegloff, 1968), “closing” (Schegloff & Sacks, 1973), and “something in between” (Robinson, 2013, p. 275)—a key feature of the overall structural organization (Kushida et al., 2017). Finally, the (micro-)activities in question are neither “pre-organized” (Robinson, 2013, p. 258) nor “standardized” (Heritage & Clayman, 2010, p. 43), lacking a normative arrangement. Rather, they seem to be a local product, inherent to the organizational constraints of the auditory objects, to which I turn below.

In our everyday life, we use various sound-making objects, e.g., vacuum cleaners, radios. Because these devices make a noise, we cannot just turn them on anytime, anywhere. The usage of these auditory objects is timing-sensitive and is a practical moral issue in interaction (Rauniomaa & Heinemann, 2014). Auditory objects can affect the sequential trajectory of the interaction, as their potential “disruptiveness” requires participants’ agreement that the “turning-on” is the next relevant action (Rauniomaa & Heinemann, 2014, p. 149). This relates to members’ practical organization of multiactivity—particularly, that of the exclusive order (Mondada, 2014). Rauniomaa and Heinemann (2014) analyzed a conversation between a home-helper and a pensioner, and they found how the home-helper orients to a set of norms that organize (un)problematic usage of auditory objects, in withholding “turning-on-the-vacuum-cleaner,” her categorial entitlement, until a possible completion of the current talk with the pensioner.

Furthermore, Heinemann and Rauniomaa (2016) showed how muting and muffing auditory objects can exhibit participants’ “increased involvement” (p. 6) in the ongoing or emerging talk. Building on the corpus used in Rauniomaa and Heinemann (2014), they argued that adjusting the surrounding soundscape can signal participants’ orientation to the talk as “making relevant a higher degree of involvement” (Heinemann & Rauniomaa, 2016, p. 24). These micro-adjustments regarding the use of auditory objects bear some unique relevance to my data, in which the ongoing activity of chord-checking is managed with two kinds of auditory objects: (a) instruments (drums, bass guitar) and (b) audio equipment (iPod, audio speakers). Both are utilized because they make sounds. However, as micro-activities unfold within the chord-checking, the participants exhibit increased involvement in one (“listening”) over the other (“playing-along”). The creation of an orderly soundscape is thus an interactional accomplishment, a multiactivity contingently (re)structured in various temporal organizations.

4. Data and methods

Data were drawn from a 10-hour video corpus of band rehearsals and studio sessions, originally recorded for a larger project. The corpus was collected in Osaka, Japan, with each session lasting about 1.5 to 2 hours. Participants included Suga, the drummer, and Takeuchi, the bassist (Figure 3). Both consented to the recording and the data use for research purposes. While they agreed to use frame grabs without any filtering, I chose to use pseudonyms for anonymization. The two’s intimacy is demonstrably reflected in the use of casual speech across the excerpts.

Figure 3. Suga (left) & Takeuchi (right)

Note. The audio speaker in question is marked with a red circle.6

Data segments involving talk were transcribed according to Burch’s (2016) transcription system, in which embodied actions are placed above the concurrent talk (see Appendix). Parenthesized numbers in the analysis correspond with line numbers in the excerpts (1, 2 ... etc.). In Excerpts 3–6, which involve no talk, I use frame grabs anchored on what I call a music arrow (Figure 4). This is to visualize the temporal unfolding of the activity-at-hand (Mondada, 2018), the participants’ close monitoring thereof, and the musical structure of the song, in a way accessible to non-musicians.

5. Analysis

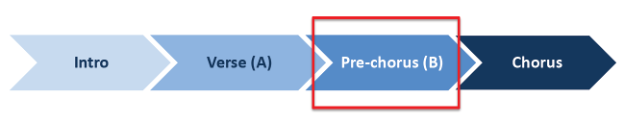

In my analysis, I focus on an activity that I have called “chord-checking.” When musicians are unsure about particular chord progression(s) in a studio session, they often use an mp3 player (e.g., iPod) to play the album version of the song in which the target segment is embedded. In my data, such chord-checking targets the “pre-chorus” (Figure 4); the participants are listening to the song in question, so that they (mostly, the bassist) can check the chords of the part building up to the chorus.

Figure 4. Basic structure of the song

As they listen to the song coming from the surrounding audio speakers, the participants can either (a) turn their instruments (e.g., bass guitar) off and focus on “listening,” or (b) play along to the music. In this part of my data, the participants begin by choosing (b). This activity, which I have called “playing-along,” helps the musicians (especially, those playing the chord-based string instruments) confirm the notes of the target segment. Once the song reaches the onset of the pre-chorus—the chords of which the bassist has claimed his uncertainty of—the significance of audibility also reaches its peak. At this point, “listening” must be prioritized over the ongoing “playing-along” (Heinemann & Rauniomaa, 2016). The chord-checking thus consists of two interrelated, yet conflicting, micro-activities: (a) listening and (b) playing-along.

As will be shown, the participants orient to each recognizable unit of the song (Figure 4) as organized in different temporal orders (Mondada, 2014). Below I focus on the moment of an organizational collision, closely examining the participants’ embodied negotiation of micro-transitions.

First, I begin with how the chord-checking is proposed through talk, embodiment, objects, and spatial resources.

Open in a separate window

Suga first checks Takeuchi’s current understanding of the overall song structure (Nanbu, 2020) by asking if he remembers the chord progression “from there” (1–2). After a brief pause, Takeuchi responds with a “mm” token (4) and gaze aversion (Frame 2). This response delay is hearable as Takeuchi’s doing “recalling” (Goodwin & Goodwin, 1986), suggesting that either the indexical referent or the target knowledge is not immediately available to him. Overlapping with the “mm” token, Suga produces a musical vocalization (Tolins, 2013), which exhibits his understanding of the response delay as recognition trouble. However, the solution by singing (Stevanovic & Frick, 2014) is visibly treated as insufficient, as is evident from Takeuchi’s head shake (6). Notably, Suga puts the sticks down on the snare head (6), and stands up (Frame 3), immediately after the vocalization—which comes before the head shake—without leaving a slot for the recipient to produce a verbal response. This abruptness suggests that Suga may have abandoned a sequentially-allocated opportunity to resolve the recognition trouble (Sacks & Schegloff, 1979) and decided to resort to a more direct solution (Svennevig, 2008; Greer & Wagner, forthcoming)—i.e., to play the song via iPod.

Suga continues, producing intra-turn self-repairs characterized by multiple cut-offs (7). The explicit labeling of the segment as “B” (8) makes the pre-chorus of the song hearably relevant to the unfolding action.7 Upon the production of Suga’s stuttered utterance, Takeuchi’s head is directed toward the audio speaker on his right (Frame 4), displaying an orientation to the equipment as an auditory object possibly relevant to the next activity. Takeuchi then shifts his gaze back to Suga (7), whereas Suga has already started walking off camera (Frame 5) to play the song with the audio equipment located right next to him.

Excerpt 2 is a direct continuation from line 8, after which Takeuchi makes a request of some sort (9), bii irete:¿ (“Can you play B?”). This turn exhibits (a) Takeuchi’s understanding of Suga’s embodied actions (e.g., standing up, walking) as projecting a move to the iPod—to be precise, to the audio equipment connected to it—and (b) his recognition of the projected results of the embodied actions. The verbal request launches friendly banter between the two, where they repeatedly “toss” requests and request grants to each other (9–13). Although this exchange is seemingly unnecessary, the banter appears to be filling in (potentially awkward) silence while Suga finds and cues the music. Takeuchi’s smile (Frame 6), their smiley voices (11–13), and most notably, the fact that their back-and-forth is not treated as unnecessarily persistent, recognizably frame the sequence as that of “play” (Bateson, 1972).8

Open in a separate window

Several observations can be noted about Takeuchi’s playful complaint (14–15). First, given its specific sequential environment, i.e., within the context of chord-checking, the complaint should be heard as not addressing the volume of Suga’s drumming in general, which would otherwise undermine the drummer’s skills—a significant threat to the face of a fellow band member. In this sense, it may be seen as a way of doing “complaining without being heard as excessively rude” (Sacks, 1992). Second, the complaint serves as an account for why their time needs to be spent checking the chord progression, and thus facilitates a smooth transition into the projected activity.9 Note that it was Takeuchi who displayed non-recognition of the chords, which may hold him accountable for impeding progressivity. Takeuchi’s account places this responsibility on Suga’s “loud” drumming. Third, renewal of the laughable allows the speaker to contribute to the ongoing humor sequence (Glenn, 2003), without interfering with the implementation of the next activity (“chord-checking”). This is enabled by the multimodal format of Takeuchi’s turn, which makes it recognizable as jocular mockery (Haugh, 2010). Finally, the design of the complaint is specifically selected among possible alternatives (Bilmes, 2015) to underscore the significance of audibility for the upcoming activity, occasioning the iPod and audio speakers as auditory objects, and their audibility as an activity-specific constraint. This allows the hearing of Takeuchi’s “mocking” complaint as a “serious” request to “play quieter,” going forward.

Suga responds to this complaint with a strong agreement (16). Although Suga is out of frame at this moment, the soft voice suggests that his orientation is being distributed to the operation on the audio equipment (Nishizaka, 2008). Soon after this, the music starts playing, and the two jointly shift to the next activity. Next, I examine the unfolding of the chord-checking, frame by frame.

At the beginning of Excerpt 3, Suga is still out of frame, whereas Takeuchi is already visibly engaged in the chord-checking (Frame 8). At this point, Takeuchi is not playing the bass and seems to be focused on “listening.” A few measures into the intro, Takeuchi starts playing the bass (Frame 9), tracing the bass line heard from the audio speakers. This visibly marks the onset of Takeuchi’s “playing-along.” During Takeuchi’s solitary engagement in the playing-along (Arano, 2020), Suga walks back into frame and to the drum set.

Open in a separate window

When Suga sits down and grabs the sticks (Frame 10), the music is halfway through the intro. Suga then initiates the playing-along, drumming the recurrent pattern of the song slightly behind the tempo. Neither visibly treats the “off-temponess” as accountable, evidence of their mutual orientation to the practical goal of the current activity (“chord-checking”). Nonetheless, they appear to be “mutually tuned in” (Schütz, 1976, p. 161) in their “inner time” (Schütz, 1976, p. 170).

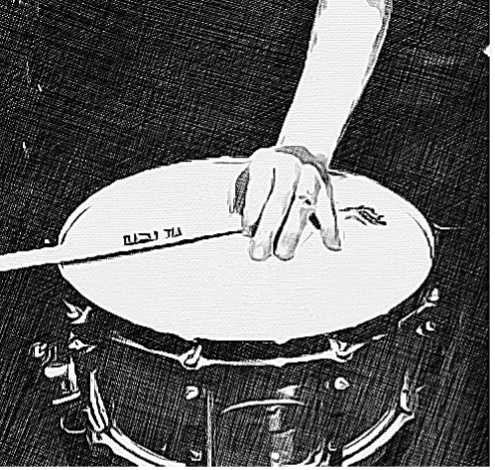

Note here that the backbeats are played on the head of the snare drum (Frame 11), which produces the loud sounds many listeners of contemporary music (e.g., rock, hip-hop) are perhaps familiar with.10 This is immediately adjusted by Suga, who changes the surface from the snare-head to the rim (Frame 12).11 Within drummer communities, the practice of clicking the rim of the snare drum with (the back of) the stick is called “closed rim shots” (Figure 5), and it is conventionally employed when the drummer needs to play in a quiet(er) volume.

Figure 5. Closed rim shot12

After switching to the closed rim shots, Suga’s drumming noticeably picks up speed and becomes closer to being on time. Therefore, the adjustment can be seen as a response to Takeuchi’s mocking complaint that Suga’s drumming was “too loud.” With this adjustment, Suga addresses the issue of audibility of the external music output source—an organizational constraint made relevant by the “turning-on” of the auditory objects (Rauniomaa & Heinemann, 2014, p. 149).13 Put differently, the surface-switching exhibits Suga’s understanding that a “higher degree of involvement” (Heinemann & Rauniomaa, 2016, p. 1) in the listening, primarily, on the part of the bassist, has been made relevant.

The song then goes into the verse. The two seem to manage the multiactivity of listening and playing-along without interferences (Frame 13), until five beats before the pre-chorus.

Open in a separate window

At this moment, Takeuchi stops playing the bass, sustaining the last note, and directs his head to the audio speaker on his right (Frame 14). The head turn is then followed by a slow rotation of the torso (Frame 15), a characteristic of double (or multiple) involvements (Schegloff, 1998). By the beginning of the pre-chorus, Takeuchi has oriented his whole body toward the audio speaker (Frame 16).

Figure 6. Rotation

In restructuring the physical and spatial configurations (Nishizaka, 2006), Takeuchi achieves temporary disengagement from the playing-along. In so doing, he makes himself fully available for the listening, which requires exclusive attention (Mondada, 2014) to the auditory objects and to the soundscape locally constituted by these objects.

Open in a separate window

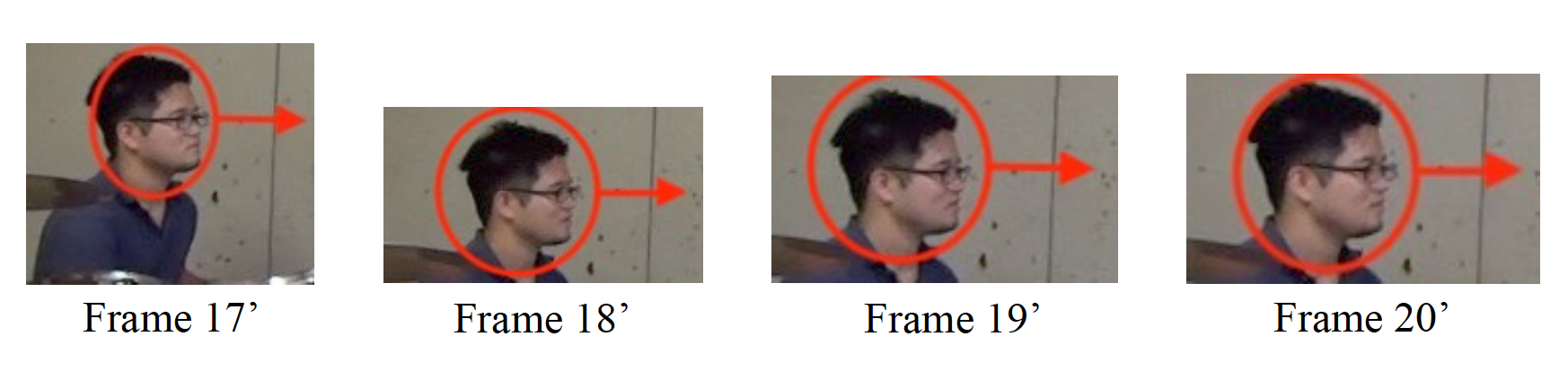

On the other hand, Suga continues the playing-along, showing no recognition of Takeuchi’s embodied proposal of the micro-transition. In response to the absence of a recognition display, Takeuchi raises his left hand and waves at Suga (Frame 17), who responds with quick, successive nods. Takeuchi’s waving thus serves as a signal for Suga to “stop playing,” the interpretation of which is warranted by Suga’s immediate compliance and disengagement from the playing-along (Frame 18). Also note that upon waving, Takeuchi does not re-orient his gaze to Suga; this strongly suggests his continued, focused engagement with the listening.

Figure 7. Waving

As he slowly re-orients his torso to the left, Takeuchi nods a few times with a “middle-distance look” (Goodwin, 1979, p. 108; Frame 19), as if confirming each note heard from the audio speaker. Takeuchi then looks down to the neck of the bass and initiates the playing-along (Frame 20), showing focused, solitary engagement (Arano, 2020) in checking the bass notes necessary for the subsequent “playing-through.” Takeuchi shifts his gaze up and down for a few seconds (Frame 21), exploring which notes properly fit in the ongoing chord pattern (Sudnow, 2001).

Figure 8. Note-checking

Structurally, the activity of “note-checking” differs from the playing-along, as it only involves the bassist, momentarily removing the drummer from the ongoing activity. Nonetheless, Suga’s embodied conduct, or absence thereof, provides evidence that the “note-checking,” like other micro-activities, is a joint enterprise (Goodwin & Goodwin, 1986). All the while Takeuchi is playing the bass (about 15 seconds in total), Suga maintains a freeze-look (Manrique & Enfield, 2015)14 at Takeuchi (Frames 17’–20’),15 and a freeze-posture, by holding the sticks still.

Figure 9. Freeze-look

The freeze-look and posture, in aligning with the activity-in-progress, exhibit Suga’s understanding that “now” is not the time for him to play along; it is the time for Takeuchi’s solitary engagement in the note-checking (Szczepek Reed et al., 2013).

Approximately five or six beats before the chorus, Takeuchi shifts his gaze toward Suga, who is still maintaining the freeze-look, while stretching out his left leg (Frame 22). When their gazes meet, Takeuchi produces successive nods and retracts the leg (Frame 23).

Open in a separate window

The restructuring of the physical configurations (Nishizaka, 2006), e.g., gaze shift, leg retraction, and the nodding, constitute an embodied announcement of Takeuchi’s availability for resuming the original activity—a (re)invitation to the playing-along. Suga responds to this invitation by reciprocating a nod (Frame 23) and air-drumming the “fill-in” (Frame 24), a musical marker used to signal an entrance into the chorus. Suga’s selection of the air-drumming (as opposed to actually playing) can be seen as his continued orientation to Takeuchi’s earlier complaint (Excerpt 2). In other words, the air-drumming may be a way of accepting an (embodied) invitation without actually doing so (Sacks, 1992).

Figure 10. Air-drumming

A few measures into the chorus, Takeuchi, again, enthusiastically produces quick successive nods, shifting his gaze up and down (Frames 25–26). Suga responds with concurrent nods and smile (Frame 26), an affiliative display of alignment (Stivers, 2008). Through the series of nods exchange (Frame 26), the participants make public—to each other and to us—their shared understanding that the larger activity of chord-checking has come to a possible completion. The activity is finally closed by Takeuchi raising his right hand (Frame 27) and Suga standing up from the drums to pause the music on the iPod (Frame 28).

6. Concluding remarks

Schütz (1976) once argued that music-making processes require “mutual tuning-in,” in which participants share, and (re)sync, each other’s subjective experience in “inner time” within a “vivid present” (p. 173). As we have seen across the excerpts, this tuning-in was a collaborative accomplishment. The chord-checking occasioned the audibility of the external music output source as an organizational constraint tied to the endogenous activity with specific temporal complexities. The participants were given two options: (a) to turn their instruments off and focus on “listening,” or (b) to play along to the music; they chose (b).

The analysis first showed how the chord-checking was proposed as a next activity. Suga’s multimodal offer to play the pre-chorus via iPod collapsed into friendly banter with a series of requests and request grants. Within this playful frame (Bateson, 1972), Takeuchi’s jocular complaint that Suga’s drumming was “too loud” made the iPod and audio speakers locally relevant as auditory objects (Rauniomaa & Heinemann, 2014), whose audibility was to be ensured for the achievement of the proposed activity. In contrast to the objects examined by Rauniomaa and Heinemann (2014), i.e., vacuum cleaners and radios, Takeuchi did not orient to the iPod and audio speakers as “interruptive”; it was the sound of the drums that was oriented to as a “noise.” The audibility was therefore designed for a specific recipient, Takeuchi, who played the only chord-based string instrument (i.e., bass guitar) present at the site. The temporal complexities of the chord-checking revealed an organizational collision between the playing-along and the listening, making relevant their “increased involvement” in the listening (Heinemann & Rauniomaa, 2016, p. 6). This conflict demanded that the participants organize micro-transitions in the exclusive order (Mondada, 2014). Due to the audibility issue, however, micro-transitions had to be negotiated solely through embodied actions, creating a complex soundscape (Rauniomaa & Heinemann, 2014) with unique contextual configurations (Goodwin, 2000).

These empirical findings contribute to various key areas within interactional research. As outlined above, the current article has unpacked the temporal complexities of multiactivity—particularly, that of the exclusive order—in a performance-based activity in which the reliance on talk is restricted. In so doing, it has offered a detailed account of how participants can work around, with various embodied practices, the organizational constraints of the auditory objects within a temporal organization characterized by specific rhythmic (i.e., musical) constraints. Considering how early CA developed out of studies on telephone conversations (Mondada, 2008), where audibility plays a crucial role, the interactional creation and management of soundscapes may be an analytic locus that deserves more thorough attention. With EMCA’s growing interest in multisensoriality (Goico et al., 2021; Mondada, 2019) and the long-established scholarship on vision (Goodwin, 1994; Nishizaka, 2000), future studies are invited to investigate hearing-in-interaction.

Acknowledgements

My sincere gratitude goes to Takeuchi for helping me with data collection and for his longtime friendship. This study would not have been possible without his help. I would also like to thank Gabriele Kasper, Jack Bilmes, Zack Nanbu, Sangki Kim, and many others, for providing insightful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript, which was originally presented at the IIEMCA 2019 panel on sports and performing arts. Lastly, I would like to thank Kristian Mortensen for his thoughtful guidance, as well as the two anonymous reviewers for their critical suggestions on my drafts. Any errors that remain are mine.

References

Arano, Y. (2020). Doing reflecting: Embodied solitary confirmation of instructed enactment. Discourse Studies, 22(3), 261–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445620906037

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind: Collected essays in anthropology, psychiatry, evolution, and epistemology. University of Chicago Press.

Bilmes, J. (2015). The structure of meaning in talk: Explorations in category analysis, Volume I: Co-categorization, contrast, and hierarchy. https://emca-legacy.info/bimles.html

Broth, M., & Keevallik, L. (2014). Getting ready to move as a couple: Accomplishing mobile formations in a dance class. Space and Culture, 17(2), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331213508483

Burch, A. R. (2016). Motivation in interaction: A conversation-analytic perspective [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

Burch, A. R., & Kasper, G. (2021). Task instruction in OPI roleplays. In M. R. Salaberry & A. R. Burch (Eds.), Assessing speaking in context: Expanding the construct and its applications (pp. 73–106). Multilingual Matters.

Bushnell, C. (2009). “Lego my keego!”: An analysis of language play in a beginning Japanese as a foreign language classroom. Applied Linguistics, 30(1), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amn033

Deppermann, A., Schmitt, R., & Mondada, L. (2010). Agenda and emergence: Contingent and planned activities in a meeting. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(6), 1700–1718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.10.006

Deppermann, A., & Streeck, J. (Eds.). (2018). Time in embodied interaction: Synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resources. John Benjamins.

Evans, B., & Lindwall, O. (2020). Show them or involve them?: Two organizations of embodied instruction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(2), 223–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1741290

Evans, B., & Reynolds, E. (2016). The organization of corrective demonstrations using embodied action in sports coaching feedback: Corrective demonstrations in sports coaching. Symbolic Interaction, 39(4), 525–556. https://www.jstor.org/stable/symbinte.39.4.525

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology. Prentice-Hall.

Glenn, P. J. (2003). Laughter in interaction. Cambridge University Press.

Goico, S., Gan, Y., Katila, J., & Goodwin, M. H. (2021). Capturing multisensoriality: Introduction to a special issue on sensoriality in video-based fieldwork. Social Interaction: Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v4i3.128144

Goodwin, C. (1979). The interactive construction of a sentence in natural conversation. In G. Psathas (Ed.), em>Everyday language: Studies in ethnomethodology (pp. 97–121). Irvington Publishers.

Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional vision. American Anthropologist, 96(3), 606–633. https://www.jstor.org/stable/682303

Goodwin, C. (2000). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 32, 1489–1522. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00096-X

Goodwin, C. (2018). Co-operative action. Cambridge University Press.

Goodwin, M. H., & Goodwin, C. (1986). Gesture and coparticipation in the activity of searching for a word. Semiotica, 62(1–2), 51–75. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1986.62.1-2.51

Greer, T., & Wagner, J. (forthcoming). Study abroad interactions in the life world. Second Language Research.

Haddington, P., Keisanen, T., Mondada, L., & Nevile, M. (Eds.). (2014). em>Multiactivity in social interaction: Beyond multitasking. John Benjamins.

Haugh, M. (2010). Jocular mockery, (dis)affiliation and face. Journal of Pragmatics, 42, 2106–2119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.12.018

Heinemann, T. & Rauniomaa, M. (2016). Turning down sound to turn to talk: Muting and muffling auditory objects as a resource for displaying involvement. Gesprächsforschung, 17, 1–28. http://www.gespraechsforschung-online.de/fileadmin/dateien/heft2016/ga-heinemann.pdf

Heritage, J., & Clayman, S. (2010). Talk in action: Interactions, identities, and institutions. Wiley-Blackwell.

Keevallik, L. (2018). What does embodied interaction tell us about grammar? Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1413887

Kushida, S., Hiramoto, T., & Hayashi, M. (2017). Kaiwa bunseki nyūmon [An introduction to conversation analysis]. Keisō Shobō.

Manrique, E., & Enfield, N. J. (2015). Suspending the next turn as a form of repair initiation: Evidence from Argentine Sign Language. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01326/full

Meyer, C., Streeck, J., & Jordan, J. S. (Eds.). (2017). Intercorporeality: Emerging socialities in interaction. Oxford University Press.

Mikkola, P., & Lehtinen, E. (2014). Initiating activity shifts through use of appraisal forms as material objects during performance appraisal interviews. In M. Nevile, P. Haddington, T. Heinemann & M. Rauniomaa (Eds.), Interacting with objects: Language, materiality, and social activity (pp. 57–78). John Benjamins.

Mondada, L. (2008). Using video for a sequential and multimodal analysis of social interaction: Videotaping institutional telephone calls. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(3). https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1161/2566

Mondada, L. (2014). The temporal orders of multiactivity: Operating and demonstrating in the surgical theatre. In P. Haddington, T. Keisanen, L. Mondada & M. Nevile (Eds.), Multiactivity in social interaction: Beyond multitasking (pp. 33–75). John Benjamins.

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878

Mondada, L. (2019). Contemporary issues in conversation analysis: Embodiment and materiality, multimodality and multisensoriality in social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 145, 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2019.01.016

Nanbu, Z. (2020). “Do you know banana boat?”: Occasioning overt knowledge negotiations in Japanese EFL conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 169, 30–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.07.005

Nevile, M. (2007). Seeing the point: Attention and participation in the airline cockpit. In L. Mondada & V. Markaki (Eds.), Interacting bodies: Online proceedings of the 2nd international conference of the International Society for Gesture Studies. ICAR Ecole Normale Suierieure Lettres et Sciences Humaines. http://gesture-lyon2005.ens-lyon.fr/article.php3?id_article=245

Nevile, M., Haddington, P., Heinemann, T. & Rauniomaa, M. (Eds.). (2014). Interacting with objects: Language, materiality, and social activity. John Benjamins.

Nishizaka, A. (2000). Seeing what one sees: Perception, emotion, and activity. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 7(1–2), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2000.9677650 target=

Nishizaka, A. (2006). What to learn: The embodied structure of the environment. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 39(2), 119–154. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327973rlsi3902_1

Nishizaka, A. (2008). Bunsan suru karada: Esunomesodorojī teki sōgo-kōi bunseki no tenkai [The body distributed: An ethnomethodological study of social interaction]. Keisō Shobō.

Pomerantz, A. (1984). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 57–101). Cambridge University Press.

Råman, J. (2018). The organization of transitions between observing and teaching in the budo class. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum Qualitative Social Research, 19(1). http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/2657

Rauniomaa, M., & Heinemann, T. (2014). Organising the soundscape: Participants’ orientation to impending sound when turning on auditory objects in interaction. In M. Nevile, P. Haddington, T. Heinemann, & M. Rauniomaa (Eds.), Interacting with objects: Language, materiality, and social activity (pp. 145–168). John Benjamins.

Reed, D., & Szczepek Reed, B. (2013). Building an instructional project: Actions as components of music masterclasses. In B. Szczepek Reed & G. Raymond (Eds.), Units of talk: Units of action (pp. 313–342). John Benjamins.

Robinson, J. (2013). Overall structural organization. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 257–280). John Wiley & Sons.

Robinson, J., & Stivers, T. (2001). Achieving activity transitions in primary-care encounters: From history taking to physical examination. Human Communication Research, 27(2), 253–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2001.tb00782.x

Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures on conversation, Vol. I & II (G. Jefferson, Ed.). Blackwell.

Sacks, H., & Schegloff, E. A. (1979). Two preferences in the organization of reference to persons in conversation and their interaction. In G. Psathas (Ed.), Everyday language: Studies in ethnomethodology (pp. 15–21). Irvington Publishers.

Schegloff, E. A. (1968). Sequencing in conversational openings. American Anthropologist, 70(6), 1075–1095. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1968.70.6.02a00030

Schegloff, E. A. (1998). Body torque. Social Research, 65(5), 536–596. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40971262

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction: A primer in conversation analysis. Cambridge University Press.

Schegloff, E. A., & Sacks, H. (1973). Opening up closings. Semiotica, 8(4), 289–327. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1973.8.4.289

Schütz, A. (1976). Making music together: A study in social relationship. In A. Brodersen (Ed.), Collected papers II: Studies in social theory (pp. 159–178). Martinus Nijhoff.

Stevanovic, M., & Frick, M. (2014). Singing in interaction. Social Semiotics, 24(4), 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2014.929394

Stivers, T. (2008). Stance, alignment, and affiliation during storytelling: When nodding is a token of affiliation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 41(1), 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810701691123

Stukenbrock, A. (2018). Forward-looking: Where do we go with multimodal projections? In A. Deppermann & J. Streeck (Eds.), Time in embodied interaction: Synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resources (pp. 31–68). John Benjamins.

Sudnow, D. (2001). Ways of the hand: A rewritten account. MIT Press.

Svennevig, J. (2008). Trying the easiest solution first in other-initiation of repair. Journal of Pragmatics, 40(2), 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2007.11.007

Szczepek Reed, B., Reed, D., & Haddon, E. (2013). NOW or NOT NOW: Coordinating restarts in the pursuit of learnables in vocal master classes. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 46(1), 22–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2013.753714

Tolins, J. (2013). Assessment and direction through nonlexical vocalizations in music instruction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 46(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2013.753721

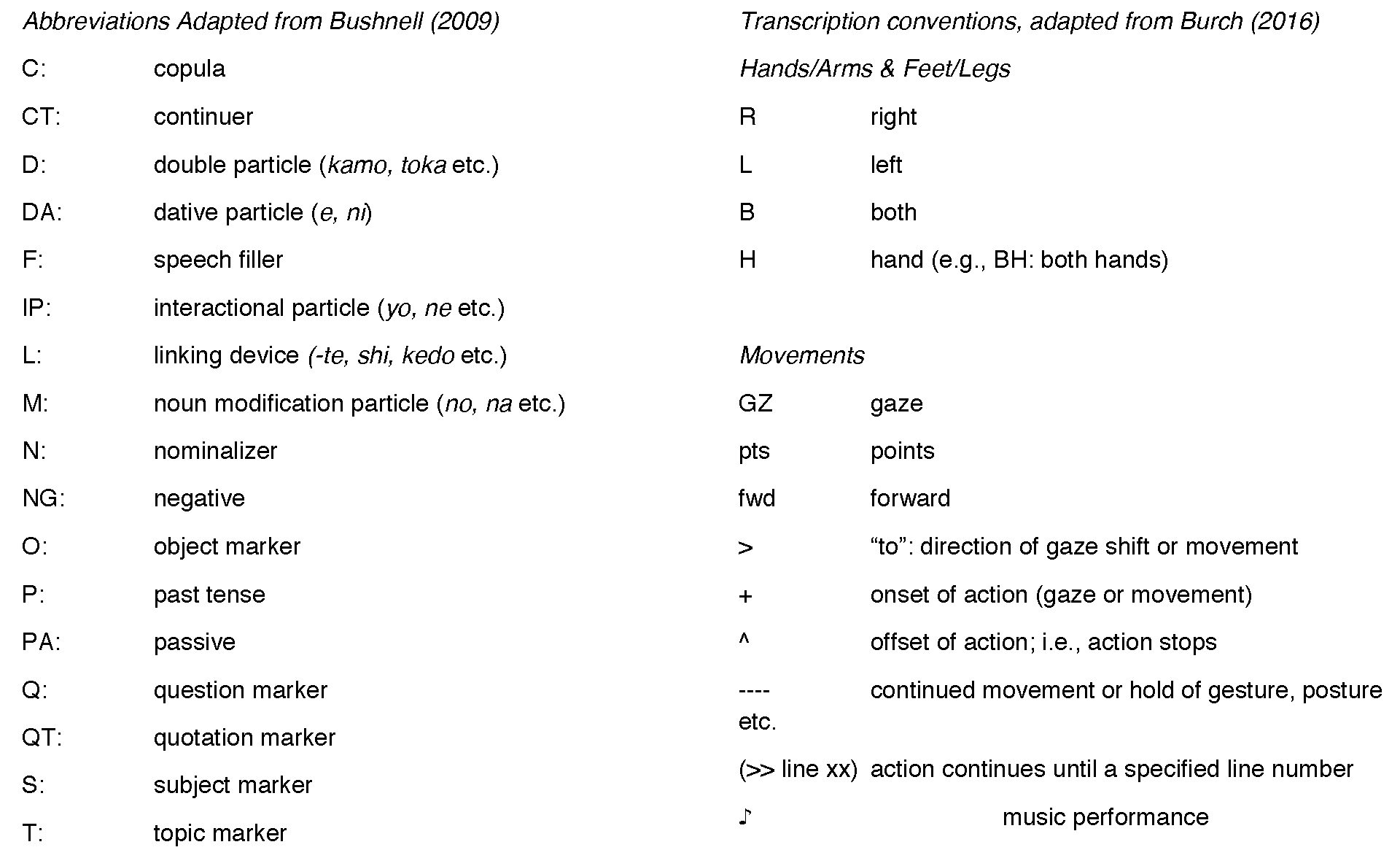

Appendix

1 See also Sacks’s lecture on “long sequences” (Sacks, 1992, Vol. II, p. 354).↩

2 Original text in Japanese.↩ 3 Terminological differences between phases and micro-activities are discussed in “Chapter 3. Multiactivity and auditory objects.” My usage of the term micro-activities relates the phenomenon to multiactivity (Haddington et al., 2014).↩ 4 Following Merriam-Webster and Oxford Dictionary, I use the terms “performance” and “performance-based” to refer to a “public exhibition of music, a play, or other form of entertainment,” which includes various physical activities, e.g., sports.↩ 5 See “Chapter 5. Analysis” for a more detailed explanation of “chord-checking.”↩ 6 Suga’s iPod is connected to audio equipment separate from the amplifier hooked to Takeuchi’s bass guitar. The equipment is located on Suga’s right (off camera).↩ 7 In Japanese band communities, musicians conventionally refer to the segment of a song building up toward the chorus as B-mero (“Part B” or “Section B”).↩ 8 It is very likely that Takeuchi’s self-repair (9) is made in response to Suga’s “stuttering” (7–8) for mocking purposes (Haugh, 2010). Takeuchi may be using Suga’s previous turns as semiotic material, upon which he can create a new relevant action (Goodwin, 2018).↩ 9 Renting a studio in Japan, though affordable, still costs the participants some money. Accordingly, it is crucial for them to plan their limited session time (usually, about two hours) wisely.↩ 10 The volume range, of course, can be adjusted with the speed and height of the stroke. Suga was actually playing in a relatively soft volume, even on the snare-head.↩ 11 Suga’s original grip, unfortunately, cannot be seen from the angle of the camera.↩ 12 The image is taken from elsewhere (https://drummagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/snare-sounds-5.jpg) and enhanced by an editing software.↩ 13 This reflexively confirms the hearing of Takeuchi’s mocking complaint as a request to “play quieter.”↩ 14 The freeze-look here is not employed to solicit other-repair (Manrique & Enfield, 2015).↩ 15 Each of these frame grabs is the zoomed-in version of Frames 17–20, indicated by the prime sign (’).↩