Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Capturing the nurse’s kinesthetic experience of wearing an exoskeleton:

The benefits of using intercorporeal perspective to video analysis

Julia Katila & Tuuli Turja

Tampere University

Abstract

In this study, we introduce a video-ethnographic study of a research process in which nursing students try on exoskeletons—wearable forms of technology that are meant to decrease lower back strain when lifting something. We adopt microanalysis of video-recorded interaction to analyze moments in which a nurse tests how her body feels with the exoskeleton. Moreover, we explore how the nurse simultaneously makes accountable—observable and reportable (Garfinkel, 1967, p. vii)—to others how her body feels “inside,” i.e. her experience of kinaesthesia, or the ability of the human body to perceive its own movements and states as a ”body-in-motion” (Sheets-Johnstone, 2002, p. 138). We reflect on how the fact that we video recorded the whole process of testing the exoskeleton with three cameras and complemented our video analysis with observations and post-questionnaires enabled us to capture some of the kinesthetic, interactive, and context-specific aspects of trying on the exoskeleton.

Keywords: cyborg, exoskeleton, nursing, video-analysis, intercorporeality, kinesthesia

1. Introduction

A significant part of nurses’ labor entails the ergonomically challenging embodied work of lifting and assisting patients who have various types of movement disabilities. As a consequence, a great number of nurses suffer from back pain and back-related injuries. In a study of robotizing care work (Turja et al., 2018), geriatric nurses expressed that they find the existing assistive equipment difficult to use, especially in the midst of their often-busy work schedule. At the same time, nurses have been found to be hesitant about bringing autonomous robots into care work and are more comfortable with the idea of new technology as their tools instead of independent actors interacting with patients (ROSE project, 2017).

In this paper, we draw upon video analysis to study a rarely investigated setting: the research process in which nursing students try on exoskeletons i.e., wearable technologies meant to support people in physically demanding tasks such as lifting heavy loads (Laevo; Figure 1). The exoskeleton has the potential to assist nurses in patient work without replacing human bodies with robots. At most, a nurse wearing an exoskeleton becomes a cyborg—a combination of a machine and a human (Haraway, 2006). However, an exoskeleton transforms the body’s kinesthetic and visual “affordances” (Gibson, 1986, p. 127) and this may influence nurses’ intimate work with patients. We still know little about how nurses experience the presence of a technology attached to their bodies.

Figure 1. Nurses wearing exoskeletons

We explore how video-recording the entire process of testing the exoskeleton with three cameras can help us to capture some of the sensorial, interactive, and embodied aspects of engaging with the exoskeleton. Moreover, we reflect on how observing the study participants and conducting post-questionnaires with them can support our video-analytic observations. We employ microanalysis of video-recorded interactions to analyze moments in which the nurses test how their bodies feel with the exoskeleton and, at the same time, make accountable—observable and reportable (Garfinkel, 1967, p. vii)—to others their “internal” feeling, i.e., their experience of kinaesthesia, or the ability of the human body to perceive its own movements and states as a “body-in-motion” (e.g., Reynolds & Reason, 2012; Sheets-Johnstone, 2002; Streeck, 2013).

2. Kinesthetic experience and the intercorporeality of bodies

Given that each body, as well as its unique context and its historical position in time, are always different, another person’s sensorial experience—whether touch, smell, or kinesthesia—can never be fully accessed (see Streeck, 2013, p. 70). However, making sensorial experience available to others is not just a challenge for the video-analysts, but also, in an important way, a concern for the participants of interaction themselves. The practical concern for the nurses in our data is how to disclose their internal kinesthetic experience of wearing an exoskeleton to other co-present participants.

We analyze various practices through which the nurses communicate to others how the exoskeleton feels at any given moment. However, while starting from the basic presumption that another person’s sensorial experience can never be entirely accessed, we also draw from the notion that expressing kinesthetic experience to others and having the others “understand” this experience is not a process that is simply mediated by bodies turning internal sensorial experiences into verbal accounts or multimodal semiotic resources (see Mondada, 2020). Instead, while we are in the copresence of others, “how it feels in a body” is often “given off” (Goffman, 1959, pp. 2–5) to others through non-symbolic expressions of a body, such as a frowning face caused by the experience of pain, or “response cries” (Goffman, 1978, p. 800) during moments of sudden changes in the experience of the body. These expressions are explicit and recognizable by other people through their own living bodies even when the specific meaning and feeling experienced is only available to the person experiencing them.

Incorporating ideas from phenomenological tradition and intercorporeal understanding of bodies, we treat the bodies of the participants as well as those of the researchers as something “not grasped [...] as an external instrument but as the living envelope of our actions” (Merleau-Ponty, 1963, p. 188). According to an intercorporeal understanding, bodies and their encounters with others are inherently multisensorial or intersensoria—in a “sensuous interrelationship of body-mind-environment” (Howes, 2005, as cited in Goodwin & Cekaite, 2018, p. 4). This refers to the comprehensive experience of perceiving oneself, others, and the world through one’s own body via a constant and mutual multisensory field of sensing and being sensed (Crossley, 1995; Merleau-Ponty, 1962, 1968; Meyer et al., 2017). Thus, from an intercorporeal perspective, sensorial practices are not just communicative resources deployed by participants to produce social actions in interaction. Instead, making “internal” sensorial experiences available to others is an embodied and intercorporeal process, solicited in and through the simultaneously sensible and sentient aspects of our bodies (see Crossley, 1995, p. 47). This reversibility of bodies, following intercorporeal understanding, thus goes beyond the instrumentalist view of bodies, as well as the representationalist understanding of embodied and sensorial behavior (Katila & Raudaskoski, 2020; Streeck, 2013). According to the intercorporeal understanding of bodies, the “inner” experience of sensing and “making sensing experience accountable” to others are not necessarily clearly separate processes, but rather are aspects of our being-with-others and the world in an embodied and material relation.

3. Exoskeletons and becoming a cyborg

When united, the human body and an exoskeleton have the potential to become a “cyborg”—a hybrid of machine and organism (Haraway, 1985/2006, p. 117). However, from an outsider’s perspective, the exoskeleton becomes a part of the nurses’ visually perceived bodies the moment it is worn—just like clothes or other wearables, while from an experienced perspective, becoming a cyborg with the exoskeleton is a feeling of being and moving in unison (see Jochum, et al. 2018). Nevertheless, this may fail to happen if the body and the material “repel” each other.

Moreover, getting used to and moving with a new technology often requires time and habitualization. According to Merleau-Ponty (1962), the body “catches” new habits and ways of being through movement. This happens, for instance, when the blind man’s stick has ceased to be an object for him, and it is no longer perceived for itself; its point has become an area of sensitivity, extending the scope and active radius of touch and providing a parallel to sight (Merleau-Ponty, 1962, p. 143).

In this way, habit enables us to amplify our experienced bodies in spaces and materials around us. However, our study focuses on the first moment(s) in which the exoskeleton is being worn; in other words, the moments before the process of habitualization occurs. Moreover, trying on an exoskeleton is fundamentally different from a blind person becoming one with a stick for instance, or a body unable to walk becoming “en-wheeled” with a wheelchair (see Papadimitriou, 2008). Although in a longer timescale the exoskeleton may have health benefits for the nurses and therefore prevent inabilities in their movement (Turja et al., 2020), the use of the exoskeleton is not necessitated by an immediate physical need. For instance, all of the nurses we studied had knowledge of how to correctly assist patients from a bed to a wheelchair without an exoskeleton. However, more generally nurses have been also found to suffer from back pain and back-related injuries, and there is a need for new assistive technology as the existing assistive equipment meant to augment the nurses’ work are difficult to use (Turja et al., 2018).

In our study, the exoskeletons were introduced in a role-playing setting, which does not reflect authentic interactions with the patients (see discussion in Stokoe, 2013). For this reason, we examine nurses trying on exoskeletons and ask how the nurses and other participants collaboratively make sense not only of the exoskeleton, but also of the whole process of testing the exoskeleton within which the tool occurs.

4. Study design, materials, and methods

We examine a process of testing the exoskeleton in which a geriatric patient is assisted from a hospital bed to a wheelchair by nursing students with and without exoskeletons. Two wearable Laevo exoskeletons used in the trial are meant to augment the user’s strength and thus make their performance of assisting a patient more robust and less burdensome.

The participants in our study design had predefined roles: Researcher 1 (R1, the coordinator), Researcher 2 (R2, the observer and video analyst), Researcher 3 (R3, the observer), Teachers 1 and 2, the patient, and two nursing students at a time (out of 16 nurses in total) in each trial context (with/without exoskeleton).

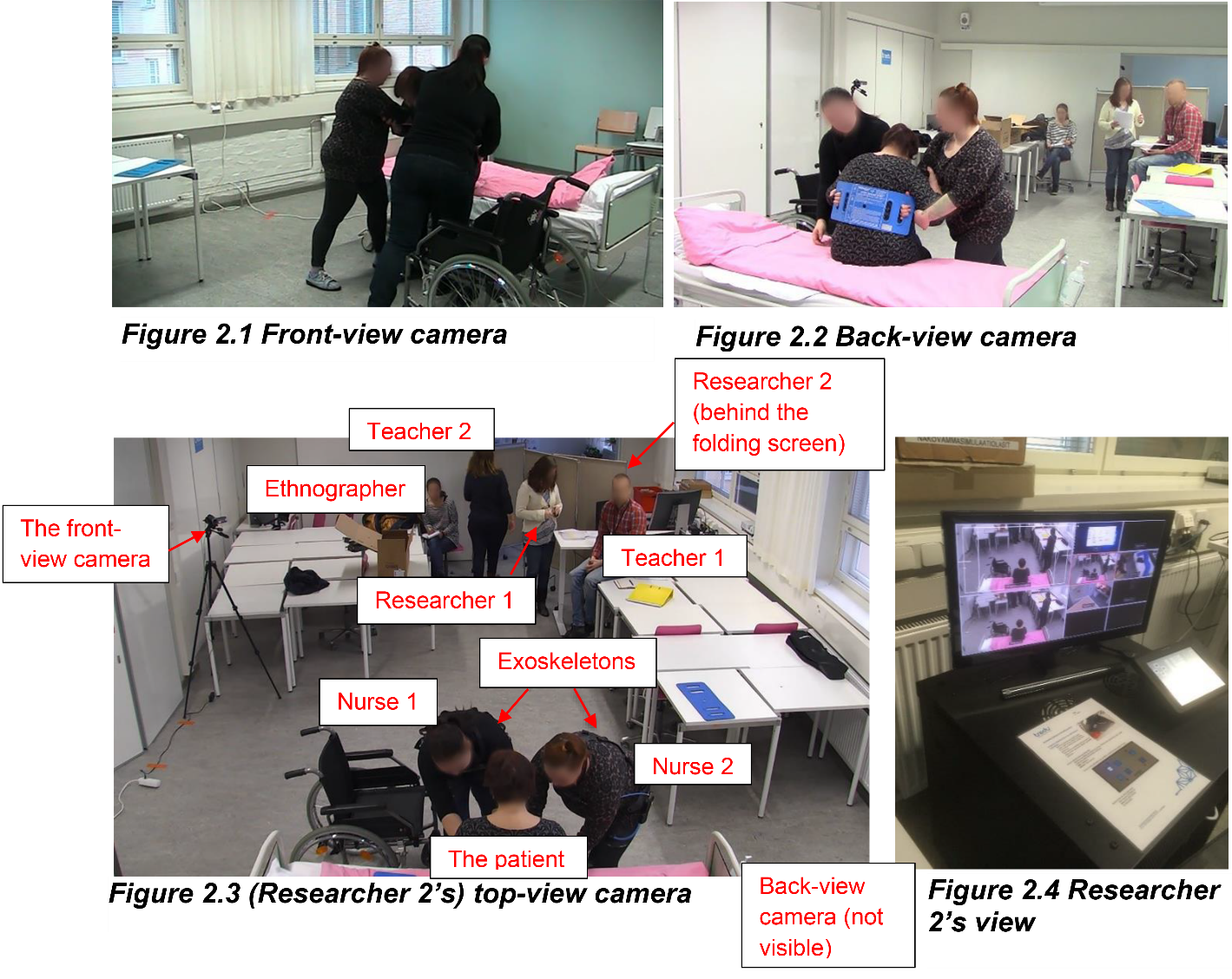

Three cameras were used to capture the front (Figure 2.1), back (Figure 2.2), and top-views (Figure 2.3) of the participants’ action. The study room was divided into two spaces or “regions” (Goffman, 1959, p. 66), wherein different activities took place. The patient-lifting space (shown from the front-view camera presented in Figure 2.1) was where the patient work happened. In this space, pairs of nursing students assisted the patient to move from her bed to a wheelchair using exoskeletons. The coordination space, then, was the backstage for the research (Figures 2.2, 2.3 and 2.4), where all preparation was done.

We were especially interested in the “backstage” interaction captured by the top-view camera and the back-view camera, and in the moments of the nurses first putting on the exoskeleton and “getting a feel” for their bodies while wearing it. We analyze in detail how the nurses explore the changes in their kinesthetic body with the exoskeleton and make this “internal” feeling accountable to others in an embodied way.

As a method, we adopt an intercorporeal (Katila, 2018; Katila & Raudaskoski, 2020; Meyer et al. 2017; Streeck, 2013) approach to video analysis of interactions. This means placing the experiencing bodies and embodied communication between the participants at the core of the analysis by examining the moment-by-moment unfolding of embodied expressions of the participants’ bodies. An intercorporeal perspective requires the researchers’ embodied and empathetic interpretation, enabled by having living and feeling human bodies of our own and basic intersubjective understanding. These interpretations rely on observable expressions of the bodies illustrated in the scenes captured on camera.

In addition to the video analysis, we reflect on how our materials enable the capturing and analyzing of these moments. We complement our video analysis with information gained from the totality of fieldwork: observations, post-questionnaires, as well as background information on the nurses, as indicated in the surveys. All of this information helps us to analyze how the differences between the bodies and their histories, as well as the institutional context and other co-present participants influence how the nurses experience the exoskeleton. This method—an intercorporeal perspective on video analysis complemented with participant observation and questionnaires—is especially suitable for studying the occurrence of sensing behavior or making accountable “how it feels in a body.” Indeed, these are not necessarily explicated in words, especially in institutional interactions with potential asymmetrical relations such as those between study subjects and researchers, or pupils and teachers.

5. Analysis

In this section, we will show and analyze three practices of a body—bending forward, stroking motion, and walking—through which one nurse, whom we call “Enni”, explores how her body feels when wearing an exoskeleton, and how the ways of movement also enable her to expose to others how she feels. We chose the following extracts because they capture the first participant getting ready to begin the very first trial of the research, putting on the exoskeleton. Hence, the whole event was new to the participants, including the researchers and the teachers.

5.1 “Bending forward” as a practice to decide whether the exoskeleton is powered

A practical challenge for the participants including the researchers is that before any trial can start, it is necessary to ensure that the exoskeleton is on and powered. The potential support provided by the exoskeleton is only directly felt by the nurse wearing it through kinesthetic experience. Although the nurse has firsthand experience of how her body feels, Researcher 1 and Teacher 1, who went through Laevo exoskeleton training, are able to help to position the exoskeleton on the nurse in accordance with the Laevo user manual.1

The nurse in the extract, Enni, had tried on the exoskeleton once before in a nursing class, and felt uncomfortable wearing it. Moreover, before Extract 1 starts, the process of adjusting the exoskeleton had already taken many minutes, and the teachers, Researcher 1 and another nurse (who at this point is not wearing the exoskeleton) were collaboratively figuring out how to fit the exoskeleton to Enni. Just before Extract 1 starts, Enni was being asked how the exoskeleton felt, to which she answered she could “manage” wearing it and wanted to proceed with the trial.

In Extract 1, Part 1 and 2, we will show how bending forward with the exoskeleton gives Enni a chance to conclude if the exoskeleton is on and powered. Moreover, it gives her an opportunity to communicate how the kinesthetic sensation of moving with the exoskeleton feels in her body. The transcription conventions used in presenting the verbal actions are simplified from the original work of Gail Jefferson (2004), and we have either blurred or drawn the faces of the participants to anonymize their identities. In addition to more conventionalized transcription signs, we have adopted the symbol @ to indicate talk said with a smiley voice. In Part 1, Enni establishes that after the last time trying on the exoskeleton she was “sore for two days”.

Extract 1 Part 1.

Open in a separate window Open in a separate windowIn Line 01, T2 asks Enni to bend forward, as this movement enables her to perceive through movement how her body feels (Gibson, 1966, 1986). Bending forward with an exoskeleton is a practice established by the participants as a kinesthetic method for a body to identify whether the exoskeleton’s power is on, because this is neither visible to outside observers nor necessarily observable by the nurse herself without bodily movement. Bending affords feeling through the body's kinesthetic sensation if the exoskeleton, which suddenly shapes and co-participates in “making” the nurse’s body (see Behnke, 1997), causes changes, such as friction, hindrances, or stickiness to one’s habitualized manner and tempo of movement.

While bending forward slowly and in a stiff manner, wearing a serious facial expression (Figure 1a), Enni responds “Yeah: (0.5) I can manage with this” (line 02), which treats the teacher’s request to bend forward not as a matter of whether the exoskeleton is powered, but whether wearing it is manageable. The choice of the word “manage” implies that there is an effort included in wearing it, yet it is bearable – a sentiment, as mentioned above, that had also been expressed just prior to Extract 1.

Sanna carefully attends to Enni (gazing at her in Figure 1a) and orients to the fact that it still is not established if the exoskeleton actually is powered, asking “is it powered now?” (line 04). At the same time, Sanna joins in with Enni with her next movement of bending forward (Figure 1b). The bodies of Enni and Sanna, facing each other, merge in a brief moment of synchronous movement, where Sanna momentarily lends her body to Enni’s body movement, in order to “try out together” whether Enni’s exoskeleton is powered. Notably, Enni’s bodily trajectory remains more modest than Sanna’s. Although the differences in the way of producing the movement in this moment certainly have to do with many things—such as differences in Enni and Sanna’s bodies more generally, the exoskeleton certainly to some extent restricts Enni’s free movement.

During the moment of collaborative bending (Figure 1b), Enni’s facial expression starts to evolve from a serious into a playful expression with her cheekbones slightly lifted and eyes lightly squinting while gazing at Sanna. Next, while straightening her body, Enni bursts into a type of response cry (Goffman, 1978) “OH OUCHH:: HEH HEH HEH ”, which is laminated with laughter (line 05), and her body bends backwards out of the flooding emotion (Figure 1c). Her facial expression is interwoven with lightheartedness and pain: She laughs with her mouth wide open, but her cheekbones, forehead and closed eyes offer a hint of a frown and communicate suffering. Her facial expressions, accompanied by aural and other embodied expressions of inner feelings, are not just semiotic resources used by Enni—they are Enni’s moment-by-moment feeling body, which expresses to others her kinesthetic sensations while moving with the exoskeleton. Perhaps attending to the expressive complexity of Enni’s laughter co-occurring with a painful expression, Sanna produces only a few laughing particles to acknowledge Enni’s laughter (line 06) and she does not join Enni in the emotional flooding.

However, something about Sanna’s way of attuning to and co-participating in Enni’s body movement allows for or even encourages Enni to express how it feels in her body. The fact that Enni had produced the same movement of bending forward just before (line 02; Figure 1a) without the overflow of emotion makes evident that the response cry was not a completely involuntary, unavoidable pain reaction, but something in Sanna’s action made it relevant to happen. Sanna joining with Enni in bending forward can be seen as a spontaneously unfolding corporeal expression of empathy (i.e., spending a moment with another body in her unease), which provides an arena for Enni to express how she feels. Enni’s emotional expression in line 05 further leads to her verbally accounting for her stance towards the exoskeleton “@I was sore for two days after the previous time@” (line 08), which she directs at Sanna and is said in a smiley tone of voice while her facial expression has now evolved into a deep frown, with her hands self-touching her belly (Figure 1d). Enni’s expression is a combination of uneasiness, discomfort and light-heartedness through laughter and the smiley tone of her voice.

After explicitly accounting her reason for unease and attitude toward the exoskeleton (line 08), next, we will analyze how Enni continues to express her unease non-verbally, accompanying moving with the exoskeleton in various ways with expressions of emotions. Just before Extract 1 Part 2, Enni is asked to lean backwards to help set up the exoskeleton and make sure it is powered (not shown in the extracts). Enni’s body appears tired and uncomfortable (Figure 1e) as the next episode of ascertaining whether the exoskeleton is powered happens:

Extract 1 Part 2, continued one minute after Part 1

Open in a separate window Open in a separate windowIn Figure 1e, it is possible to glean from Enni’s backwards leaning posture that she is not entirely comfortable. In addition, her hands are at her belly to maintain her body posture while bending backwards, and her facial expression—which is not directly attended to by the participants but is visible in the video—is serious. Her whole body is therefore a communicative field: it is feeling and expressing what is going on in her body at that moment. Bodies and their postures, to follow Streeck’s (2018, p. 326) expression, inhabit multiple timescales at once. This means that bodies are not only attending to the temporality of the ongoing moment, but also shaped by the biological, living body that tires from activity according to the time of the day. Thus, Enni’s here-and-now embodied emotional expression—unease and discomfort—toward the activity is enmeshed with the tiring, biological, and living body.

In the next move (Figure 1f), the postures of the bodies are transformed, as the exoskeleton produces an auditory action, a “clicking” sound (line 01). The moment the clicking sound happens, by carefully zooming in on the video, it can be observed that Enni’s body trembles slightly, and her facial expression transforms from serious (Figure 1e) to a hint of a frown (Figure 1f). Thus, Enni’s lived sensation of the tightening of the buckles shows in her facial expression, demonstrating uneasiness through shrunken eyes and tightly sealed lips. This is interpreted by R1 as the exoskeleton’s signal that its buckles have finally been fastened successfully (“Ohh (.) like tha:t” in line 02).

Although it is already nascent in the minor change in Enni’s “body idiom” (Goffman, 1963, p. 33), T1 asks her again to bend forward, this time specifying the request to bend forward as a practice to figure out if the exoskeleton is powered (line 03). Besides again offering a means to feel one’s body through movement, bending forward also provides Enni a moment to demonstrate to the others how the exoskeleton feels.

In Figure 1g, responding to the teacher’s directive, Enni bends forward with a slowness that is noticeable: in a fashion that is kinesthetically available to the nurse and visually accessible for the participants as well as the video analyst. At the same time, in line 04, Enni says “oh yes this is ˚nowh totally powered˚”—inserting an “extreme formulation” (Pomerantz, 1986) of “totally” into her utterance, instead of simply saying that the exoskeleton is powered. Accordingly, without being explicitly asked, her way of moving and responding to the teacher’s question is much more informative than simply stating whether the exoskeleton is powered. Her utterance, which she says in an emotionally rich out-breathy voice, to borrow Heath’s (2002, p. 206) words, “voices difficulty” or demonstrates suffering through the physical manifestation of effort and uneasiness, which “transpose[s] inner suffering […] to the body’s surface” through gesture and bodily conduct (Heath, 2002, p. 603). Thus, while perceiving how it feels in her body, she is doing so demonstratively, even performatively. Through the practice of bending forward, Enni is able to communicate sensorial aspects of a body that are not explicitly topicalized in speech (see McArthur, 2018), thus “showing rather than claiming” her inner sensations (Heath, 2002, p. 610).

Although visible for the researcher through the video, at this point, the other co-participants do not show explicit appreciation of this demonstration. They are instead preoccupied with the practical maintenance of the exoskeleton and the research process. Perhaps partially as a result of her expression not being directly oriented to, Enni turns her demonstration into a moment of “private laughter” in front of others (Figure 1h, lines 07 and 09). This is, in a way, her own response or “metacommentary” to her previous action and what she was and is feeling in the moment. At the same time, Enni is exhibiting an attention to inward feeling by keeping her eyes closed and her face in a frown, while self-touching the location where the exoskeleton is presumably causing discomfort (Figure 1h). However, her “private” expression is still designed to be noticed by others, enabling them to understand that the exoskeleton feels uncomfortable in the spot that she touches. Consequently, rendering it “laughable” (Jefferson, Sacks & Schegloff, 1987) seems to serve the purpose of reconciling the potentially face-threatening situation and embarrassment of having to present oneself in front of others while feeling awkward in one’s body (see Goffman, 1956; Heath, 2002).

5.2 Imitating a stroking motion while wearing an exoskeleton

Directly after the previous Extract 1, Enni starts to walk toward the official testing area. However, her counterpart Sanna, who at this point is not wearing the exoskeleton, initiates a corporeal action sequence of imitating a “body technique” (Mauss, 1973) of stroking the patient’s legs. This is a tactile practice commonly conducted by nurses approaching a patient to assist them in their movement: for example, getting up from a bed. The stroking motion is meant to help the patient get up by stimulating and activating their legs.

Extract 2 Part 1

Open in a separate windowIn Figure 2a, Enni is still laughing to herself and adjusting to her new bodily state. She then starts to walk away from the teachers (Figure 2b). During Figure 2b, Sanna suggests that Enni test how it would feel to stroke a patient with the exoskeleton on (lines 01–04). Enni redirects her walk toward Sanna, but transformed by this new habitus with new restrictions, she walks with side-straddle steps (Figures 2.b–2d), moving with noticeably greater slowness and stiffness than before, and inhabiting a style of walking that has the sensorial qualia of effortfulness. Harkness (2015) refers to qualia as signals that materialize phenomenally in human activity as sensuous qualities, such as sound shapes, warmth, and gentleness. According to Harkness, these sensuous indexes, which are recognizable, felt and experienced across modalities, “[destabilize] the polarity between ‘material bodies’ and abstract symbols” (Harkness, 2015, p. 581). Qualia thus offer a way of talking about and analyzing meanings embedded in the way or “style” (see Merleau-Ponty, 1962) of moving which cannot be treated as semiotic resources “used” by bodies, as they are inevitably embedded in the way the body lives and moves.

This fashion of moving—in this case effortful, which marks the movement from “effortless” (Cuffari & Streeck, 2017, p. 190)—is primordially a kinesthetically felt qualia, but becomes available to others, who are, to some extent, visually able to access the “felt” aspects of moving the body in a certain “effortful” fashion (see Katila, 2018, pp. 42–46). This ability of basic level kinesthetic empathy (Reynolds & Reason, 2012) enables the human body—including the analyst’s body—to be able to gather some information about another body’s kinesthetic experience through associating it with certain qualia.

By means of an effortful gait, Enni starts to walk toward Sanna. Then, the bodies of Enni and Sanna—spontaneously and in a shared rhythm—emerge into a brief moment of synchronous, interkinesthetically (Behnke, 2008, p. 144) coordinated action, in which they enact “stroking the patient’s thighs”. They bend forward to the imagined height and location of the patient’s thighs and, side-by-side, move their hands as if stroking an actual patient (Figures 2d–2e). This movement of their bodies is something that is relevant in actual health care interactions with patients and, as it is often done by two nurses together, it makes sense to perform the body trajectory in pairs. The movement of imitating stroking a patient together allows Enni and Sanna to collaboratively use the exoskeleton in an intelligible practice (see Raia, 2018)—a body movement that makes sense in the work of nursing—and feel how it feels to do it while one nurse is wearing an exoskeleton and the other is not. In the video, and similar to Extract 1, it can be observed that Enni’s bodily trajectory remains more modest than Sanna’s, suggesting that the exoskeleton restricts Enni’s free movements.

In the next moment, Enni continues to move toward the patient. Then, explicitly attending to the effortfulness of Enni’s walking, T1 says, “for the sake of the research, I wonder if Enni should just walk around for a moment,” which gains a minimal nod from Researcher 1 (not shown in the extracts). After that, as seen in line 01 of Extract 2 Part 2, T1 reframes his suggestion and addresses it to Enni.

Extract 2 Part 2

Open in a separate windowIn Figure 2f, visualizing his verbal action by producing a circling gesture with his hands, T1 prompts Enni to walk around for a moment (line 01). Through this expression, T1 topicalizes Enni’s manner of walking and thus gives “explicit” evidence that the co-present participants also responded to Enni’s way of moving with the exoskeleton as different than her way of moving before wearing it.

As an immediate response and partially overlapping with the teacher’s talk, Enni twists her head to gaze at T1 (Figure 2f) and co-participates in the teacher’s action by saying, ”YEAH RIGHTHHH” (line 02). By treating the teacher’s turn as laughable, Enni again manages the prospective face-threatening aspect of her body and gait being the center of attention.

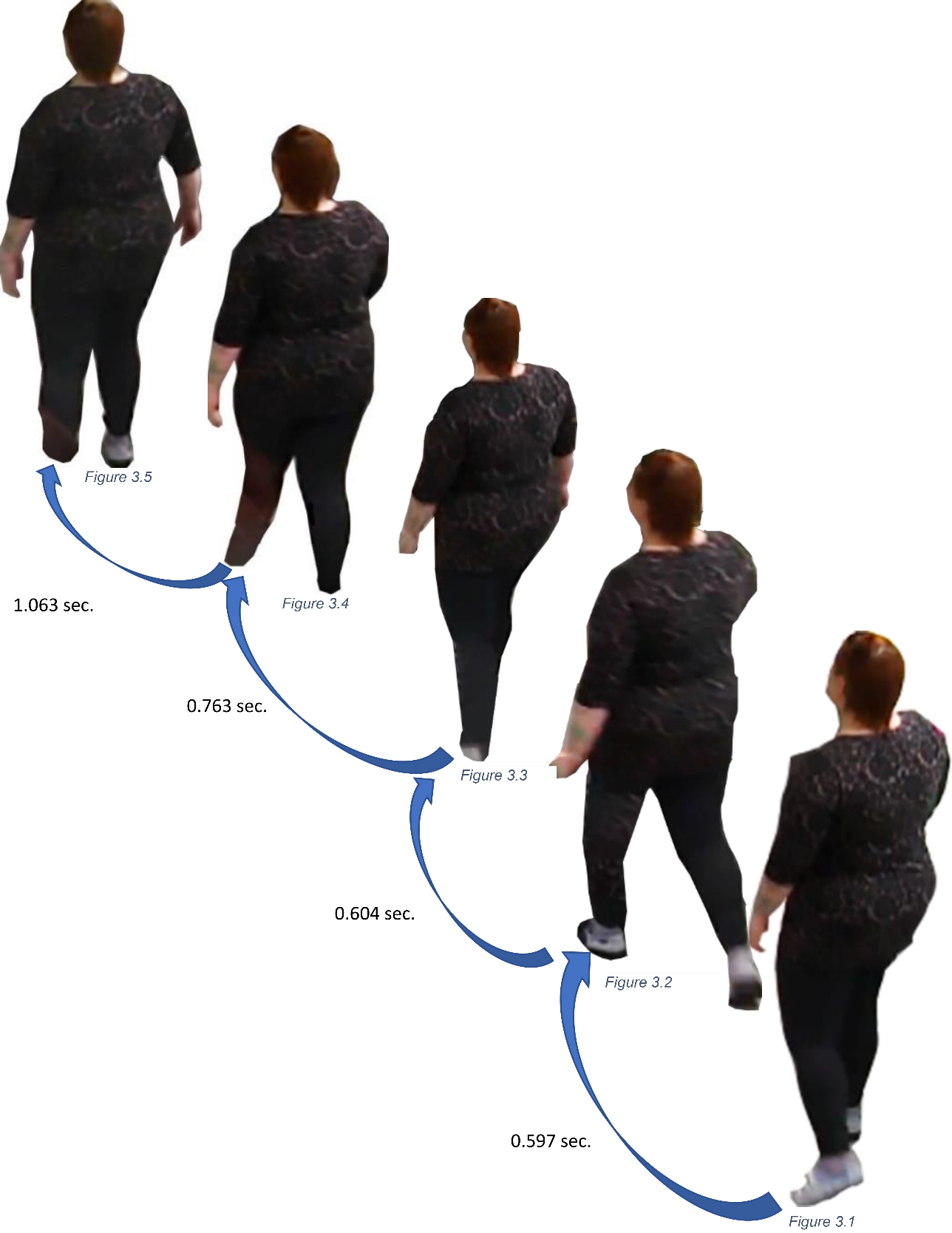

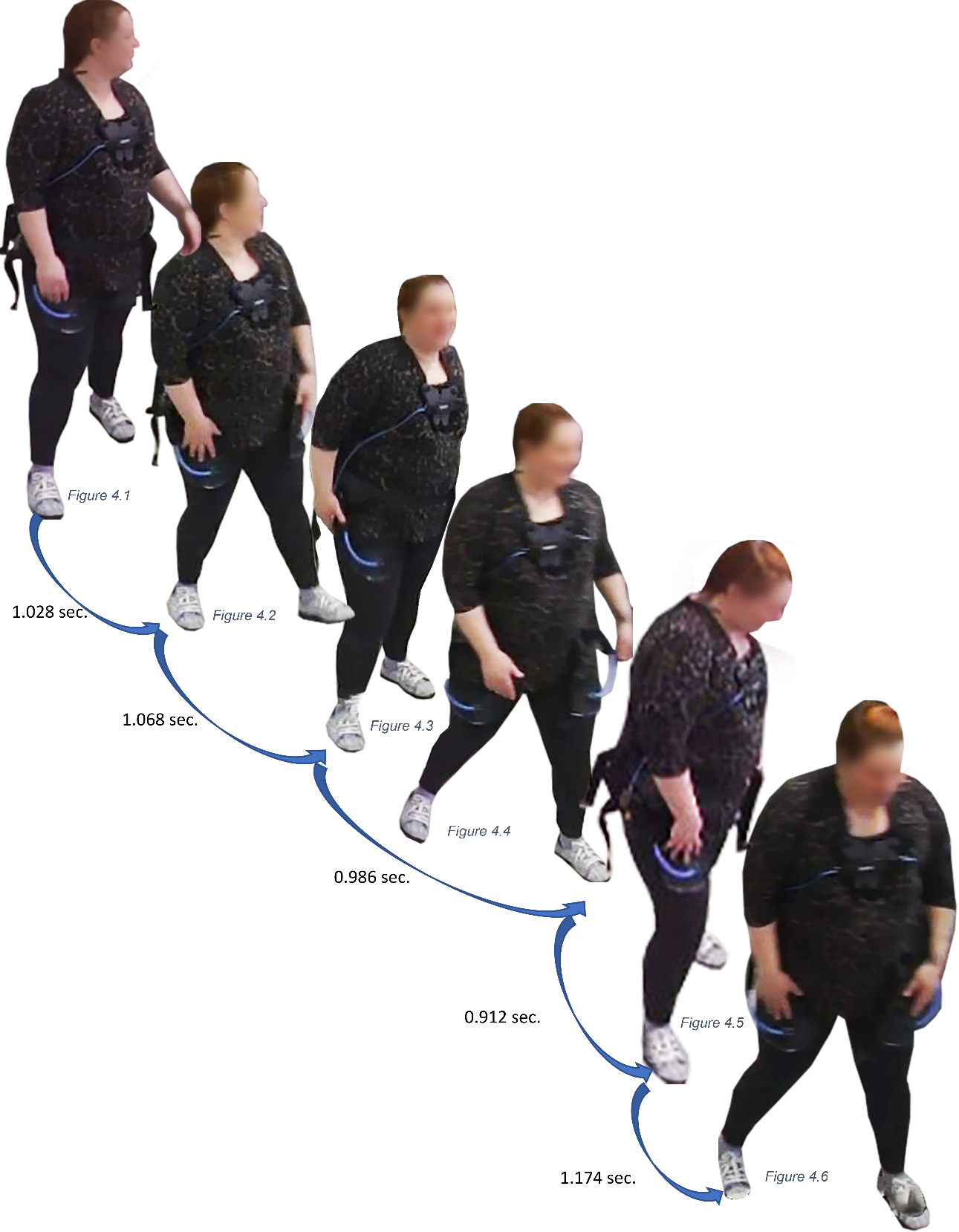

After her way of walking has been addressed, Enni continues walking toward the bed in a similar vein, with her hands holding her thighs at the spot where the exoskeleton imposes pressure. In this way, she makes publicly visible how she is experiencing her body differently: Her movement is less free and more burdensome (Figures 2g–2j). Touching the exoskeleton while walking in a heavy manner also shows that Enni is reacting to the exoskeleton as something that is not part of her body, but rather as something that hinders her body and its movement. Let us compare her steps before (following Figure 3) and after (following Figure 4) putting on the exoskeleton. Figure 3 presents the steps Enni took when she was walking toward the teachers to put on the exoskeleton, whereas Figure 4 recaptures Enni’s gait while she walked toward the patient (also shown in Extract 2 Part 2).

Figure 3. Walking toward putting on the exoskeleton

Figure 4. Walking with the exoskeleton

The medium tempo of Enni walking without the exoskeleton (Figure 3, approximately 0.75675 sec per step) was faster than when she walked with the exoskeleton (Figure 4, approximately 1.0336 sec per step) and the style of her walking was more straightforward without the exoskeleton. In this way, the careful video analysis and video recordings of the backstage behavior enable us to compare the different ways in which Enni and the other nurses moved and performed their bodies at different points in the research process.

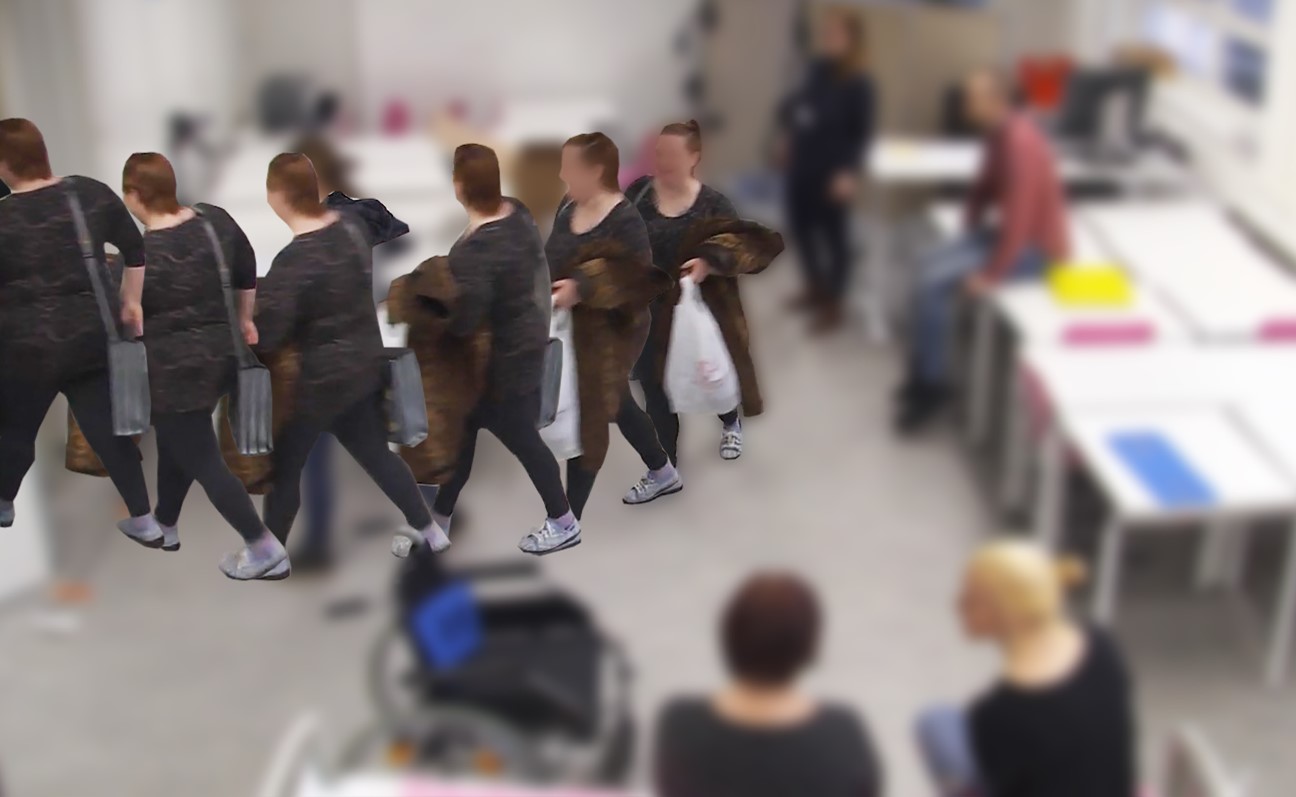

However, it is crucial to note that it is not possible for anyone to walk “neutrally.” Walking is not only an interactional accomplishment, requiring navigation with others co-present (Ryave & Schenkein, 1974), but also a situation in which each individual is always, in any given moment, walking in a context-relevant and culturally-specific fashion (Mauss, 1973). Furthermore, each person’s gait is a part of their body’s historically accumulated personal style, a bit like a signature. For instance, in the “before-gait” shown in Figure 3 (approximately 0.75675 seconds per step), Enni walked a little bit slower than she did when she walked outside of the research room after the study (approximately 0.5634 seconds per step, see Figure 5). Thus, the fashion and tempo of walking also reveal information about the walker’s extent of familiarity and emotional stance toward the “destination”. In the pre-exoskeleton walk (Figure 3), Enni walks in a slower manner, as one may walk toward places in which they do not quite know what to expect, whereas when walking outside of the room (Figure 5), there was no such uncertainty in Enni’s steps, and the effortless gait showed that the kinesthetic experience of walking in itself, or where to go, was not the current concern.

Figure 5. Walking outside of the research room

In his micro-ethnographic study, Streeck (2017) analyzes auto shop owner Hussein’s different ways of walking during one day, and how his manner of walking varied depending on the time of the day, type of activity, and person he was engaged with. Streeck (2017) writes:

Close observation of Hussein’s manner of moving, of his gait and bearing and of the way he moves his arms when he walks, clues us into some of the many ways in which body motion can be meaningful beyond the immediate, instrumental tasks that it addresses and solves [and that] walking is more than a means of transporting, that its manner can reveal social information about the person walking. (pp. 8-9)

Walking, moving and wearing our bodies in certain ways is ingrained with “body symbolism” (Goffman, 1963, p. 33) and embedded with qualia (Harkness, 2015), which are, in different ways, both kinesthetically and visually available. It is in this way that our bodies and their fashion of moving is experienced by and expressive to others —even if the social meanings embedded in the style of moving are often “seen but unnoticed” (Garfinkel 1967, p. 36). This is an essential point in terms of studying sensorial behavior and making a sensing body accountable to others through video analysis. “How it feels in a body” or “how it feels to move” is seldom topicalized in words. Yet these things are constantly being communicated to others, especially in a setting where it is particularly relevant to communicate how it feels in a body, such as in the case of testing an exoskeleton. Such expressions of body are observable if the movements and manner of moving of whole bodies are taken into account in the analysis, and the body is treated as a sentient being, not merely something which produces sensorial resources.

Importantly, a crucial part of the manner of Enni’s walking and moving—before and after wearing the exoskeleton—is that she is a participant in a research project and an object of other people’s observation. Like Enni, almost all of the other 15 nurses we studied also changed the way they walked with the exoskeleton, some with less dramatic changes, others explicitly citing a “robotic” style of moving. Therefore, we were able to see how cultural “style” (Mendoza-Denton, 1999) and representations of “a robot walking,” as well as, potential expectations that some kind of transformation is supposed to happen while wearing the exoskeleton, played a role in walking with the exoskeleton. In any case, the bodily technique of walking—enabling one to “[perceive] the world through feet” (Ingold, 2011, p. 33; Smith, 2021/this issue)—bestowed the nurses with an opportunity to experience and express their bodies and “internal” sensations in a context that did not otherwise provide them with space to elaborate how they feel.

Unlike most other nurses we studied, Enni clearly expressed negative feelings about wearing the exoskeleton. The video analytic observations presented here were supported by the post-questionnaires. Compared to the total sample, Enni and Sanna reported in the questionnaires that they would not be able to easily learn to use the exoskeleton or to assist others with it, and they were on the average more pessimistic about the exoskeletons making care work any easier. In addition, the pair stood out, by reporting that using the exoskeleton would increase stress in their work and by remarking on how the exoskeleton is controlling the user rather than the users controlling the exoskeleton (see Turja et al., 2020 for details of the questionnaires).

6. Conclusions

In this microanalytic case study, we analyzed how a nurse we called Enni tested how her body felt with an exoskeleton and made her own embodied sensation accountable —observable and intelligible—to others. We investigated how Enni—moving with the exoskeleton in certain, practice-relevant ways—explored her body’s affordances, felt directly by her alone, through the sense of touch and kinesthetic experience. However, we also reflected on the possibility that through visually available “kinesthetic empathy” (Reynolds & Reason, 2012) and the ability of bodies to extend and translate socially meaningful qualia (Harkness, 2015) across senses (such as kinesthesia and vision), human beings are able to glean some information about other people’s sensorial experience. Moreover, the emotional expressions—such as an expression of unease and discomfort, which co-occurred with moving in a certain fashion, enabled learning details about how, in a given moment, it feels “inside” of another body.

The detailed analysis of Enni’s embodied expression revealed that, in the studied moments (Extracts 1–2), she did not treat herself and the exoskeleton as moving as a cyborg organism. Rather, her bodily orientation exposed how the exoskeleton hindered her movement and caused discomfort in her kinesthetic experience. However, our study only covered some of the first moments Enni moved with an exoskeleton and compared this with her movement without the exoskeleton. Thus, our data does not stretch to speculate as to what would happen if she would continue to use the exoskeleton over a longer period of time.

Although we treat these studied emotional expressions and ways of moving as part of living and feeling a sentient and sensible body, our materials enabled us to analyze how the expressions were also produced performatively to make them accountable to others. The fact that we drew upon video materials from various angles, as well as having video-recorded the whole research process, enabled us to analyze the ways in which Enni enlivened her experience of moving with the exoskeleton for performative purposes. Video recording allowed us to compare the movements between settings in which Enni moved with and without an exoskeleton. Moreover, participating in and observing the research process at the moment in which it happened enabled us to analyze some of the theatrical aspects of “demonstrating suffering” (Heath, 2002) when moving with the exoskeleton in this particular environment.

We especially observed the subjective, context-specific, and (moment-by-moment) interactive aspects of moving with and sensing how the exoskeleton feels. Each nurse acted differently with the exoskeleton, and it fitted better for some nurses than others, simply because (their) bodies are uniquely shaped and they have unique ways of moving, whereas forms of technologies are often designed for “ideally” sized bodies (Søraa & Fosch-Villaronga, 2020). However, we also noticed similarities between how the nurses made their kinesthetic experiences accountable to others, especially having to do with the special, artificial context: Right at the moment that the exoskeleton was first put on, most of the nurses somehow made accountable the changes in their body, and many of them performed more effortful, clumsy, or “robotic” ways of moving and walking.

We found that the nurses’ kinesthetic and affective experiences of wearing an exoskeleton are crucially molded by the moment-by-moment interaction between the participants. For instance, in Extract 2, Enni’s fellow nurse Sanna initiated a collaborative embodied trajectory with Enni that involved trying how the exoskeleton feels “together”. Sanna’s initiation not only topicalized Enni’s embodied experience, but also—by unfolding into a brief interkinesthetically coordinated moment—corporeally co-participated in Enni’s kinesthetic experience. Otherwise, Enni would not have felt her body with the exoskeleton through that specific movement.

In a historical, cultural, and moment-by-moment timescale, we as human beings co-participate in “making” one another’s bodies (Behnke, 1997, p. 198) and their sensorial experiences, through shaping how we move when sensing and feeling together. Phenomenologically informed video analysis provides a powerful method to uncover how bodies sense and feel—and make their sensations and feelings accountable to others. This is enabled by treating the bodies of the participants not as simply “using” sensorial resources, but as fundamentally expressive, sensing and sentient beings whose affective expression is, at a basic level, recognizable by others.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Emil Aaltonen Post Doc Pooli/Emil Aaltonen Foundation grant “The Role of Touch and Intimacy in Health Care Encounters”, and the Academy of Finland, the Strategic Research Council (project ROSE, decision numbers: 292980 and 314180). We also want to thank the reviewers for their insightful comments to earlier versions of this paper, and Elise Rehula for drawing the pictures of faces from our transcripts.

References

Behnke, Elizabeth A. (1997). Ghost gestures: Phenomenological investigations of bodily micromovements and their intercorporeal implications. Human Studies, 20(2), 181–201.

Behnke, Elizabeth A. (2008). Interkinaesthetic affectivity: A phenomenological approach. Continental Philosophy Review, 41(2), 143–161.

Crossley, Nick (1995). Merleau-Ponty, the elusive body and carnal sociology. Body & Society, 1(1), 43–63.

Cuffari, Elena & Streeck, Jürgen (2017). Taking the world by hand. In C. Meyer, J. Streeck, & J.S. Jordan (Eds.), Intercorporeality: Beyond the body (pp. 173–201). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garfinkel, Harold (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Gibson, James J. (1966). The senses considered as perceptual systems. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Gibson, James J. (1986). The ecological approach to visual perception. Hillsdale (N.J.): Erlbaum, 1986. Print.

Goffman, Erving (1956). Embarrassment and social organization. The American Journal of Sociology, 62(3), 264–271.

Goffman, Erving (1959). Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Doubleday Anchor.

Goffman, Erving (1963). Behaviour in public places: Notes on the social organization of gatherings. New York: Free Press.

Goffman, Erving (1978). Response Cries. Language, 54, 787–815.

Goodwin, Marjorie Harness & Cekaite, Asta (2018). Embodied family choreography: Practices of control, care, and mundane creativity. New York: Routledge.

Haraway, Donna (2006). A cyborg manifesto: Science, technology, and socialist-feminism in the late 20th century. In J. Weiss, J. Nolan, J. Hunsinger, & P. Trifonas (Eds.), The international handbook of virtual learning environments (pp. 117–158). Dordrecht: Springer.

Harkness, Nicholas (2015). The pragmatics of qualia in practice. Annual Review of Anthropology, 44, 573–89.

Heath, Christian (2002). Demonstrative suffering: the gestural (re)embodiment of symptoms. Journal of Communication, 52(3), 597–617.

Howes, David (2005). Introduction: Empires of the senses. In D. Howes (Ed.), Empire of the senses: The sensual culture reader (pp. 1–20). Oxford: Berg.

Ingold, Tim (2011). Being alive: Essays on movement, knowledge and description. London & New York: Routledge.

Jefferson, Gail (2004). A sketch of some orderly aspects of overlap in conversation. In G. Lerner (Ed.), Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 43–59). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Jefferson, Gail; Sacks, Harvey & Schegloff, Emanuel A. (1987). Notes on laughter in the pursuit of intimacy. In G. Button & J.R.E. Lee (Eds.), Talk and social organisation (pp. 152–205). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Jochum, Elizabeth A.; Demers, Louis-Philippe; Vorn, Bill; Vlachos, Evgenios; McIlvenny, Paul B. & Raudaskoski, Pirkko L. (2018). Becoming Cyborg: Interdisciplinary approaches for exoskeleton research. In EVA Copenhagen 2018 – Politics of the Machines – Art and After (pp. 1–9).

Katila, Julia (2018). Tactile intercorporeality in a group of mothers and their children: a micro study of practices for intimacy and participation. Tampere: Tampere University Press. Doctoral dissertation.

Katila, Julia & Raudaskoski, Sanna (2020). Interaction Analysis as an Embodied and Interactive Process: Multimodal, Co-operative, and Intercorporeal Ways of Seeing Video Data as Complementary Professional Visions. Human Studies, 43, 445–470.

Mauss, Marcel (1973). Techniques of the body. Economy and Society, 2, 70–88.

McArthur, Amanda (2018). Getting pain on the table in primary care physical exams. Social Science & Medicine, 200, 190–198.

Mendoza-Denton, Norma (1999). Style. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 9(l-2), 238 -42.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1962). Phenomenology of perception. London and Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1963). The relations of the soul and the body and the problem of perceptual consciousness. In A. Fisher (trans.), The structure of behavior (pp. 185-224). Boston: Beacon Press.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1968). The visible and the invisible: Followed by working notes. Northwestern University Press.

Meyer, Christian; Streeck, Jürgen & Jordan, J. Scott, (Eds.) (2017). Introduction. In Intercorporeality: Emerging socialities in interaction(pp. xiv–xlix). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mondada, Lorenza (2020). Audible sniffs: Smelling-in-interaction. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 53(1), 140–163.

Papadimitriou, Christina (2008). Becoming en‐wheeled: The situated accomplishment of re‐embodiment as a wheelchair user after spinal cord injury. Disability & Society, 23(7), 691-704.

Pomerantz, Anita (1986). Extreme case formulations: A way of legitimizing claims. Human Studies, 9, 219–229.

Raia, Federica (2018). Identity, tools and existential spaces. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 19, 74–95.

Reynolds, Dee & Reason, Matthew, (Eds.) (2012). Introduction. In D. Kinesthetic empathy in creative and cultural practices (pp. 17–25). Bristol: Intellect.

ROSE project (2017). Robotics in Care Services: A Finnish Roadmap. http://roseproject.aalto.fi/Figures/publications/Roadmap-final02062017.pdf

Ryave, A. Lincoln & Schenkein, James N. (1974). Notes on the art of walking. In R. Turner (ed.), Ethnomethodology (pp. 265–274). Harmondsworth: Penguin

Sheets-Johnstone, Maxine (2002). Relationality and caring: An ontogenetic and phylogenetic perspective. Journal of Philosophy of Sport, 29, 136–148.

Søraa, Roger Andre & Fosch-Villaronga, Eduard (2020). Exoskeletons for all: The interplay between exoskeletons, inclusion, gender, and intersectionality. Journal of Behavioral Robotics, 11(1), 217–227.

Stokoe, Elizabeth (2013). The (in)authenticity of simulated talk: Comparing role-played and actual interaction and the implications for communication training. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 46(2), 165–185.

Streeck, Jürgen (2013). Interaction and the living body. Journal of Pragmatics, 46(1), 69–90.

Streeck, Jürgen (2017). Self-making man: A day of action, life, and language. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Streeck, Jürgen (2018). Times of rest: Temporalities of some communicative postures. In A. Deppermann and J. Streeck (Eds.), Time in embodied interaction synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resources (pp. 325–350). Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Turja, Tuuli; Saurio, Riika; Katila, Julia; Hennala, Lea; Pekkarinen, Satu & Melkas, Helina (2020). Intention to use exoskeletons in geriatric care work: Need for ergonomic and social design. Ergonomics in Design: The Quarterly of Human Factors Applications, 1–4.

Turja, Tuuli; Van Aerschot, Lina; Särkikoski, Tuomo & Oksanen, Atte (2018). Finnish healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward robots: Reflections on a population sample. Nursing Open, 5, 300–309.

1 For a Laevo user manual, see www.laevo-exoskeletons.com ↩