Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Moving Out of View: Managing Participation and Visibility in

Family Video-Mediated Communication

Yumei Gan1* & Darcey K. deSouza2

1Shanghai Jiao Tong University

2Oklahoma State University

Abstract

The technological affordances of video-mediated communication (VMC) allow family members to sustain relationships at a distance. In this paper, based on 45 hours of video recorded family video calls in the US and China, we use the methodology of Conversation Analysis to examine one recurrent activity in our corpus: people moving out of camera view and becoming not visible during their video calls. We show how, depending on interactants’ current involvement in the call, temporarily suspending visibility occurs in tandem with suspending participation, but not always. This study makes unique contributions to reconceptualizing the relation between the technological affordances of visibility and people’s mobility and participation in family video calls, furthering the notion of what “open” connections look like in practice.

Keywords: affordances, video-mediated communication, visibility, mobility, family communication, conversation analysis

1. Introduction

The use of video-mediated communication (VMC) has become a pervasive characteristic of contemporary life. Given its technological affordances of going “beyond being there” (Hollan & Stornetta, 1992) and its ability to stimulate a “connected presence” (Licoppe, 2004), VMC provides distinct opportunities to reduce the limits of time and space (McLuhan, 1964) in people’s professional and private lives. In particular, participating in video calls can be understood as an accountable activity with specific relational goals (Harper et al., 2017).

An increasing number of scholars have drawn attention to the important role of VMC in workplace (Due & Licoppe, 2021) and family contexts (Cabalquinto, 2018; Castles et al., 2014; Lim et al., 2016) in our increasingly global world. Most relevant for our work, VMC has become an important and often omnipresent activity for families who are geographically separated from each other, either temporarily or for the long term (Livingstone, 2002, p. 67). How family members interact with each other across geographical distance and time zones to sustain their relationships at a distance has become an important research question (e.g., Baldassar et al., 2016; Beck & Beck-Gernsheim, 2014; Madianou & Miller, 2012; Rintel, 2013). For example, in adult sibling relationships, the process of communicating when apart functions to simply “stay connected” (Hamwey, Rolan, Jensen, & Whiteman, 2019, p. 2499). People value VMC for long-distance relationships mainly because of its technological affordances of visibility, or the possibility to see and to be seen (Madianou & Miller, 2012). As Harper, Warton, and Licoppe (2017) write concerning the importance of “seeing” in family VMC: “distributed, fragmenting families solidify themselves not through what they think when they are separated, but by letting each other see each other’s shape, their form, their body” (p. 305); the possibility of seeing and being seen enhances the feeling of being together and engaging with each other in a virtual space.

In this paper, we explore how families manage the affordance of visibility in VMC. We adopt the methodology of Conversation Analysis to examine one recurrent activity that happens in our data corpus: instances when people routinely move out of view and render themselves not visible for remote parties during family video calls. We ask: how do people manage visibility in VMC? More precisely, how do they treat moments when there is a lack of mutual visibility? Drawing on naturally occurring video calls among remote family members, we detail the empirical practices that people use when managing lapses of visibility in these calls.

2. Background

2.1 Technological Affordances

VMC technologies present different affordances, or technological capacities (Anderson & Robey, 2017; Gibson, 1977; Hutchby, 2001) than other information and communication technologies (ICTs) (e.g., text messages, phone calls): they allow for the possibility of being able to see and be seen. Fox and McEwan (2017) refer to this as social presence, or “the feeling that interactants are near and sharing the same experiences together” (p. 302). Visibility has been shown to be an important affordance of VMC: it allows people to do collaborative activities from afar such as “showing” and “sharing” body parts, objects, and domestic events, achieving a mutual sense of “being together” online (Due & Lange, 2021; Licoppe & Morel, 2014; Licoppe, 2017a; Searles, 2018).

However, the technological affordance of visibility is not without limitations. VMC allows for the possibility of visibility, but this is not a “given”, rather, it requires people’s interactional work in order to achieve because screens are limited in size and can provide “only reduced visibility” (Nielsen, 2019, p. 192). For example, people need to work to position themselves within the camera view so that remote parties can “see” them (Gan et al., 2020; Licoppe & Morel, 2012).

2.2 Orientations to Visibility

Research on visibility in VMC has examined how people orient to problems of visibility. Some studies have examined the limitations of video view in video calls, arguing that people orient to the issue of visibility in video calls and treat the video-mediated interaction as asymmetric (Heath & Luff, 1992; Arminen et al., 2016; Due & Licoppe, 2021; Hjulstad, 2016). Brubaker, Venolia and Tang (2012) show that people orient to the limitations of the video frame in VMC in relation to how it constraints one’s physical behaviour to a limited field of vision. Furthermore, interactants must work and adapt to the technology, such as medical professionals who partake in embodied history taking despite a lack of sensory access (Due & Licoppe, 2021).

Research also shows that people engage in interactional work in order to be visible in the limited size of frame available in VMC. In video call openings, people take time to arrange their face and head on screen in order to present themselves as visible and available for interaction, thus treating being visible as an accountable component of openings (Ilomäki & Ruusuvuori, 2021; Licoppe & Morel, 2012). In particular, Licoppe (2017b) shows that interactants treat appearances in VMC openings as noticeable, and that when they are understood as “first” appearances, the projected next action is a greeting. In addition, the possibility of visibility functions as an important conversational resource for families interacting in video calls. As Zouinar and Velkovska (2017) find, interactants may perform “noticings” of others’ environment and what is visible within the frame of video calls in accomplishing topic shifts. Thus, visibility (or appearing on a screen) has implications for interaction in VMC.

How people position and hold their camera may also impact visibility. For example, people may complain when devices shake, or when the remote party does not frame what they are showing correctly within the camera view (Gan et al., 2020). Furthermore, when auditory or visual barriers impact workplace video calls, interactants may produce embodied noticings to orient to these troubles (Oittinen, 2021). That is, while video cameras provide people with the possibility of seeing and being seen, video camera angles are restricted and limited. The limited frame size requires that people are in the camera view if they want to be seen.

Although the issue of visibility is seen as a critical affordance of VMC for helping people to sustain their relationships, and studies show how interactants themselves orient to the limitations of the camera view during video calls, not many studies have explored how people manage their virtual visual access in video calls in situ. Thus, we know relatively little about how visibility is treated and managed in personal video calls. Our research builds on the literature of visibility in VMC, finding that visibility is not always a main concern for people engaging in family video calls, depending on the locally ongoing activities. In other words, people do notorient to visibility at all in certain interactional contexts during VMC. This is related to what C. Goodwin and M. H. Goodwin (2004) describe in terms of “participation”. According to them, participation refers to actions demonstrating “forms of involvement” (p. 222), and people achieve this through a range of different activities, including embodied participation such as gestures, orientations, and postures. Following the Goodwins’ insights, we find that in video calls people can demonstrate their engagement not only by remaining visible but also by maintaining their participation framework in other ways (i.e., continuing to talk during a momentary lack of visibility).

2.3 Family Video Call Practices and Activities

Research on family video calls differentiates between two main practices: “focused conversation” and “open connections” (Kirk et al., 2010, p. 138). They find that with focussed conversations, the video connection occurs during a limited time, but for the entirety of a conversation. In contrast, with open connections, video calls are left on for an unspecified amount of time with no pressure to talk or remain in the camera view. Similarly, studies have shown that family video calls may consist of different types of activities: parallel and shared (Neustaedter & Greenberg, 2011). In parallel activities, interactants do different activities (e.g., cooking, watching TV) on their own, whereas in shared activities interactants partake in activities together (e.g., sharing meals, watching TV together). Importantly, Neustaedter and Greenberg (2011) find that during parallel activities interactants are not necessarily visible during the duration of the video call and that “conversation would routinely come and go” (p. 5). In their research on public Google hangouts, Rosenbaum, Rafaeli, and Kurzon (2016) find that even though there is the possibility for remote visibility, this does not “necessarily make participants remain visually—or verbally—engaged” (p. 45).

This research shows how visibility is not necessarily a permanent condition for video calls; there are types of calls, and types of activities, in which people move out of view of the screen. However, we do not yet know what makes this a possibility for remote interlocutors. In co-present interactions, people often account for leaving a room or place (Goodwin, 1987). We ask, then, how do interactants treat temporary “leavings” in VMC, and how do “leavers” accomplish the activity of leaving? In other words, what are the rules for maintaining visibility in remote family interactions?

2.4 Multiple Involvements

One important finding about how people use technologies is that people are able to establish simultaneous multi-activity participation frameworks (Kenyon, 2010; Raymond & Lerner, 2014) to deal with multiple involvements at hand. Prior research shows that the operation of these multiple involvements varies based on the type of technology being used. For example, DiDomenico, Raclaw, and Robles (2018) show that people use nonverbal and verbal techniques to attend to mobile text summons while simultaneously managing their participation in co-present conversation. That is, they work to engage in mobile texting and co-present interaction simultaneously. However, in the context of Skype calls (VMC), Licoppe and Tuncer (2014) show that people may put the video call “on hold” in order to attend a summons (e.g., a doorbell, an incoming phone call) to manage the multiple involvements during a video call, temporarily suspending their participation in the video call to attend to other simultaneous activities.

The present paper also considers the relationship between issues of visibility and multiple involvements in video calls. We examine how interactants present themselves as active participants in video calls with multiple concurrent involvements while simultaneously managing issues of visibility (i.e., being seen by their remote co-interlocutors). We know that in family video calls people are often not “in view” of the camera for the duration of a call (i.e., Kirk et al., 2010; Neustaedter & Greenberg, 2011), but what do they do when they temporarily leave the camera view? We also know that people may put video calls “on hold” to attend to other summons (Licoppe & Tuncer, 2014), but how do they manage other multiple concurrent involvements and the issue of visibility? Are their leavings treated as accountable, or can interactants merely come and go as they please, orienting to the affordances of visibility in VMC as something that is transient and not always necessary? In focussing on interactants’ orientations to visibility in these family video calls, we can understand more about how the video component of VMC impacts remote family communication.

3. Data and Methods

The data in this paper are based on two videorecorded corpora from American and Chinese families. Both corpora are video recordings of naturally occurring video calls among family members. In these calls, there is no particular reason for the call other than to simply keep in touch (Drew & Chilton, 2000). Both corpora consist of family video calls involving families with very young children and often include talk between young children and remote grandparents, parents, and/or aunts/uncles. No instructions were given to the families concerning specific activities to be recorded. Overall, for this study we examine 76 video calls from 34 different families, totalling 45 hours of data.

The first data corpus was collected by the second author and contains a collection of 31 video calls (approximately 15 hours in total) from one American family who frequently uses FaceTime to communicate with distant family members. The video calls last from 2 minutes to 40 minutes, with the average call lasting approximately 26 minutes, and always include Liz (Mom) and her two children, Stacy (three years, six months old) and Henry (fourteen months old). In this corpus, the mom and her children use a desktop computer, and they use FaceTime to call various family members (e.g., grandparents, Dad (who is currently training for the military), aunts, cousins, etc.) who use either an iPad or iPhone. The data were collected via QuickTime recordings from Liz’s computer that captured live video of her computer screen, so the video itself shows what Liz, Stacy, and Henry can see when they are calling on FaceTime. This corpus is in American English.

The second data corpus was collected by the first author and contains a collection of 45 video calls from 33 Chinese families. These video calls are between migrant parents (who move to cities to work) and their “left-behind” children (who stay in rural areas to live with their grandparents) (Ye & Pan, 2011). In this corpus, people use smartphones and the instant messaging app WeChat for video calls. The calls range from 20 minutes to 65 minutes in length, with the average call lasting approximately 22 minutes. Child participants are all under three years old, so the calls always involve caregivers (all caregivers are grandparents in the data), young children (sometimes there are elder siblings present), and migrant parents. The data were collected in the grandparents’ locations in rural China. The recordings were collected with the combination of an external camera and a screen-capturing application on the grandparents’ phones. This corpus is in the Chinese Sichuan dialect used in the area of Zigong.1

This study adopts the methods of Conversation Analysis (CA), which examines the details of social interaction. CA research proceeds in an inductive fashion in order to identify and analyse candidate phenomena, focusing on interactants’ own orientations within the data (Sidnell & Stivers, 2013). Importantly, just as Arminen and his colleagues (2016) describe the focus of interactional work on mediated interactions, our goal is to show how “technologies and media can be shown to be both relevant and consequential with respect to the sequential organization of interaction” (p. 292). In particular, we examine how interactants orient to visibility during VMC.

After noticing that people frequently leave the view of the camera in the data, we built a collection of instances (N=141) where participants temporarily move out of the camera view. We define being “out-of-view” as a moment in which an interactant becomes temporarily not visible to their remote interlocutors, after which they return (and become visible) to the video frame. Cases were firstly transcribed using Jeffersonian transcription system (Hepburn & Bolden, 2017), and then we adopted Mondada’s (2014) transcription conventions to highlight the relevant embodied actions during the interactions. In particular, in order to show the process of one participant leaving the camera view, we included relevant screen shots and put all screen shots at the end of the transcript. The cases presented in the findings here are representative of our collection as a whole.

4. Findings

In the analysis, we present two distinct ways in which interactants temporarily move out of view of the video camera (i.e., suspending mutual visibility) during family video calls. We build upon Kirk, Sellen, and Cao’s (2010) work on “open” connections, finding that with these “open” connections (where interactants frequently come and go out of view) people suspend their visibility in video calls in two different ways depending on their involvement in other activities. First, when interactants are engaged in multiple concurrent activities, they may suspend both their visibility (by moving out of view) and their audio participation (by ceasing to verbally participate in the call while they are out of view). However, in these instances “leavers” provide announcements when they suspend their visibility and audio, orienting to the fact that their participation in that moment relies on their visibility on screen. In contrast, when interactants are engaged in “open” connections, but with a primary engagement of participation in the video call, they may momentarily suspend their visibility, but not their audio (or verbal participation in the call). In these cases, interactants move out of view of the screen, but continue talking with the remote interactants, thereby demonstrating their ongoing participation in the video call.

4.1 Suspending Visibility and Participation

In this first section, we show two cases where “leavers” momentarily suspend participation in video calls by becoming not visible and also stopping their verbal participation. With these cases, we show how interactants treat suspending participation in this way as accountable in this VMC setting: they orient to the suspension of visual and verbal participation as something that requires explanation by the person leaving, using phrases such as “hold on”, “I am getting a coffee”, “I gotta let (the dog) out”, etc. It is pertinent to note that these moments are not long in duration; oftentimes, interactants are only out of view for a few seconds, yet they still pre-empt these momentary lapses in visibility and participation by providing accounts for their remote interlocutors. Both of these cases occur during calls that are “open” (Kirk et al., 2010) in nature, however, the interactants still announce their leaving in order to make others aware of their actions.

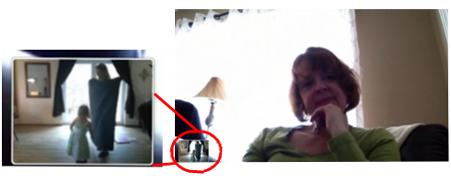

In Extract 1, we show a case in which a “leaver” pre-emptively orients to an upcoming temporary lack of visibility and verbal participation when the remote parties are engaged in multiple concurrent activities. In this case, Grandma is talking on FaceTime with Mom, Stacy (three-and-a-half years old), and Henry (fourteen months old). Grandma is using FaceTime on her iPad while Mom has FaceTime open on a desktop computer (see Figure 1 for the perspective of the video-recording from Mom’s desktop).

Figure 1. View from Mom’s desktop: Grandma is on the main screen. From the very small window on the bottom left corner, we can see Mom and Stacy’s self-view.

Stacy has just finished showing Grandma several new dresses Mom bought for her, and at the beginning of the extract she asks for Mom’s permission to run to a blanket Mom is setting up for them to sit on in their living room (lines 01-11). Grandma then produces an announcement (lines 12-14, see Images 1a-1d) before she starts moving out of view. Here, Grandma pre-empts her forthcoming lack of visibility and verbal participation in the call by announcing her upcoming actions.

Extract 1. Pepper

Open in a separate windowThere are multiple concurrent activities occurring at the start of this extract (Goffman, 1963; diDomenico & Boase, 2012); Stacy and Mom are engaged in a request sequence about a play activity, running towards the blanket, (lines 01-11) at the same time they are on the video call with Grandma. During this request sequence, Mom in particular orients herself and her children towards the call with Grandma: she sets up a blanket on the floor (line 02) and sits down on it with Henry facing Grandma (line 06). That is, even though Mom is engaged in a side sequence with Stacy, she demonstrates her ongoing orientation to the call with Grandma with her embodied behaviors. Grandma, at the same time, is oriented to something off-camera (presumably the dog), as she looks off screen starting in line 06 until line 11, when her gaze returns (just prior to her announcement of her leaving).

After Mom grants Stacy’s request to run to the blanket, Grandma initiates a sequence with “=ka:y I gotta let Pep- Pepper? I gotta let Gra:cie out I’ll be right ba:ck.” (lines 12-14). This turn is prefaced with a version of “okay”, which indicates more to come (Beach, 1993). Then there is an announcement of what she is going to do next (let out the dog, Gracie2). Note that this announcement is formulated with “gotta”, which implies that this is a task that Grandma needs to do. It also includes the duration of time needed to complete the task (that she will be “right” back), indicating that this will be a temporary suspension of her participation in the video call, which also implies that the other parties (i.e., Mom, Stacy, and Henry) will be there when she returns and resumes her participation in the call.

Grandma starts to get up and move out of the camera view just as she finishes her turn with “back” (line 14). That is, sequentially, Grandma’s announcement occurs before her actual movement out of view. Furthermore, Grandma does not wait for a confirmation from anyone on the other end of the call; the announcement itself stands alone as sufficient in informing the remote parties what she is doing, and thus why she is leaving the view of the camera. Grandma also suspends her verbal participation in the call after she leaves; she does not continue talking with Mom and Stacy while she is gone.

This case shows how, even though there are multiple ongoing activities occurring on both sides of the video call, as Grandma is not necessarily actively participating in the call at this particular moment in time (i.e., Stacy and Mom are discussing Stacy’s play and Stacy herself is looking off-screen), Grandma still orients to her forthcoming absence by announcing it before she leaves, doing so just after Mom grants Stacy’s play request, and Grandma herself returns her gaze to the video call (line 16). In so doing, Grandma indicates her upcoming lack of visibility and verbal participation in the call, something that she appears to need to do verbally because of the multiple concurrent ongoing activities (i.e., because Stacy and Mom are engaged in another concurrent ongoing activity, if Grandma did not say something they may miss her “leaving” and then potentially inquire as to her whereabouts when noticing she is gone). Overall, this case shows how people orient to the contingencies of “open connections” in VMC when there are multiple concurrent involvements.

Next, Extract 2 shows how people account for their leavings even when they are not the primary interactant in the video call. In this case, Grandma (GMA) and Jia (two years) are talking with Jia’s dad on video call. Jia’s dad is a migrant worker who works far away from home, and Jia’s grandparents take care of her. In this call, Grandpa (GPA) is holding the smartphone for Jia (see Images 2a-2d below). Grandpa holds the smartphone in front of Jia’s face, thereby orienting to Jia as the main interactant in the video call with her dad; Grandma is sitting next to Jia but is not currently actively involved in the call. We show how Grandma temporarily leaves the view of the camera in line 06 after announcing that she is going to peel an apple for Jia, even though she is not the current primary interactant on the call at that moment.

Extract 2. Peel

Open in a separate windowAt the beginning of this segment Jia places an apple in front of the smartphone, thus showing it to her dad (line 01, Image 2a; Searles, 2018). Dad responds by asking her, “are you giving (the apple) to me?”, thereby treating her showing as a “give” action (Kidwell & Zimmerman, 2007), even though they are not co-present (and he cannot actually physically take it from her). He then continues in line 03 saying, “I won’t peel it for you”. Dad’s use of “won’t” here is ambiguous; we do not have evidence to confirm whether Dad is orienting to his lack of physical co-presence or whether he uses this utterance to indicate that the child “eats too much” (as we see later in line 08, Dad refers to Jia as “greedy”). Regardless of which action Dad performs with this turn, we see that Jia responds by passing the apple to her Grandma (line 05). Grandma treats this passing as an embodied request, responding by describing her future action (i.e., that she is going to peel the apple) (line 06), said as she gets up and leaves the view of the camera. That is, Grandma treats Jia’s pass as an embodied request in lieu of Dad’s lack of co-presence and ability to be able to actually physically peel the apple for her, and then accounts for her forthcoming absence. Dad smiles and teases Jia, “are you so greedy?” (line 08), orienting to her (presumed) desire to eat the apple as one of gluttony.3 Despite the fact that Dad does not respond directly to Grandma’s account for leaving, his assessment-formatted question “are you so greedy?” addressed to Jia displays his understanding that Jia is going to eat again because Grandma has gone to peel the apple for her. With this turn, the video call continues between Jia and Dad without Grandma’s participation.

Overall, this case shows how Grandma precedes her leaving with an account for leaving. Before she leaves the view of the video camera, she provides a reason for why she is leaving, i.e., she is going to peel the apple. Like other calls between migrant parents and their children, this call is largely focused on the child (Gan et al., 2020), and the ongoing interaction at this moment is between Jia and Dad. However, even though Grandma is not a primary interlocutor in the call at the moment in which she leaves, she still accounts for her temporary forthcoming absence from the video call, making it known to her remote interlocutor that she is leaving, and thus temporarily suspending her visibility and verbal participation.

In both Extracts 1 and 2, “leavers” account for their absences before they go out-of-view and suspend their visibility and verbal participation in the call. That is, they treat their forthcoming momentary lack of visibility and participation as requiring an explanation, and provide that explanation before moving out of view. This shows how interactants expect each other to be in view and ready to interact in calls that are “open” in nature, even when there are multiple concurrent ongoing activities occurring on both sides of the video call (e.g., Extract 1) or when they are not primary interlocutors in the call at that moment (Extract 2).

Goodwin (1987) distinguishes between “an account for unilateral departure” versus “an official account for leaving” in co-present interactions. We see here that when interactants cease participation in a video call, they provide announcements for why they are moving out-of-view. That is, they do not just say that they are moving out of view or temporarily leaving the call, but they give concrete reasons for why this movement occurs (i.e., what they are going to do when temporarily not visible and partaking in the call). This adds to our understanding of how the video calls in these family interactions operate. Even in “open” connections when family members are engaged in multiple current ongoing activities, or when one is not a primary participant in the call, they are expected to be visible and available in these video calls, or when they are not going to be visible and able to audibly participate, even for a moment, they pre-empt these moments with explanations for their upcoming behaviour in order to make their temporary leavings understood by their co-interactants. This shows how families treat the video and audio components of VMC as core to its usage: visibility as well as verbal participation are expected in these family video calls, even though this type of participation may vary. These expressions of future actions (e.g., announcements and accounts) serve a particular purpose in these cases: if interactants simply left the call when engaged in another activity, or were not a primary participant, their remote interlocutors might not notice their temporary absence. This reshapes our understanding of “open connections” in family VMC. That is, “open” does not necessarily mean that you can move out of view ”reely”, without providing accounts for your actions and whereabouts. Instead, “open connections” reveal a situated level of participation, wherein participants treat their leavings as accountable and meaningful.

4.2 Suspending Visibility but not Participation

In this second set of cases, we examine instances in “open” interaction calls where the “leaver” is not enaged in multiple concurrent activities, and when they move out of the view of the camera they continue talking (thus maintaining their verbal participation in the video call). We show that interactants suspend their video participation while still maintaining the interaction by participating verbally, orienting both to the “open” connection of the video call, and the idea that a temporary lack of visibility is permissible in this type of communication as long as verbal participation continues. That is, because they are not engaged in any other activities than the video call itself, and because they are the primary interactant at that point in time, they may only participate in the call verbally at times (and come and go visually).We show that, first, although announcements may be provided (e.g., Extract 3), they are not always provided in this type of leaving context (e.g., Extract 4).

Extract 3 occurs in the same video call as Extract 2, with Grandpa holding the phone facing Jia and Grandma. At this moment, Jia is not actively involved in the call, and Grandma (GMA) is chatting with migrant Dad about his son Yuan (5 years old), who is not present for this call because he is sleeping. In this extract, Grandma pre-empts her temporary movement out of view by explaining that she would like to show Yuan’s exercise book to Dad, thus announcing her leaving, however, she still continues talking while out of view, maintaining the audio connection and her verbal participation in the call (lines 11-15).

Extract 3. Two

Open in a separate windowAt the beginning of this segment Grandma reports on her discussion with Yuan about his nap (lines 01-02). Then, in lines 04-06 Grandma tells Dad about Yuan’s writing accomplishment, finishing with a pre-show (Searles, 2018) saying “>you look< at the two:: that he wrote is very funny” (line 06), projecting that she will show the number two that Yuan wrote. In this context the pre-show “>you look< at the two::” can be understood as a directive to Dad to look at the two that Yuan wrote, but as there is currently no “two” available for him to see, it functions as a pre-show for an item that needs to be retrieved. Further, Grandma treats this “two” as “very funny”, thereby treating the upcoming show as something that is comical (presumably because of the form Yuan used to make the two).

After no uptake from Dad, Grandma then asks, “do you want to look or not?” (line 08), here explicitly asking Dad if he wants to see the “two”, projecting a yes or no response. However, Dad does not respond. Grandma takes Dad’s lack of response to be due to connectivity issues, saying “Ohis internet signal is not goodO”, an utterance that appears to be directed in general to her co-interactants (co-present and/or remote) because it is not directed to anyone in particular, and no one responds. However, in this context, it can also be understood as responsive to Dad’s non-response to her pre-show because as she says this, she gets up (presumably to start getting the exercise book to show Dad) and walks away (line 10). Note that this temporary moment of lack of visibility is pre-empted by her prior talk (the pre-show), which explains the reason why she is leaving the view of the video-camera.

As Grandma continues walking away, she announces why she is moving out of view. First she repeats her previous turn from line 06 with “look at :: the two that he wrote” (line 11). As Dad has yet to produce a response to her initial attempt at a pre-show, this second pre-show attempt functions as the pursuit of a response (Pomerantz, 1984). Grandma then continues with the specific announcement “=I am getting it to oshow youo”. With this turn, Grandma specifically explains what she is doing off camera as she is doing it. This announcement serves to give a reason for her visible absence (even with the lack of response by Dad as to whether or not he wants to see the child’s writing). By announcing her lack of visibility in this way, as she moves out of view and as she remains out of view, Grandma continues her participation in the video call in spite of her lack of visibility. Furthermore, despite the fact that Grandma has left the camera view, she continues talking to Dad in lines 14 to 15, reporting on Yuan’s writing practice and progress. Grandma eventually walks back to the phone (line 24) and shows the exercise book to Dad by saying “(you) have a look” (starting in line 30).

This case shows how temporarily suspending video access in a call does not necessarily mean that participation in the call has to be suspended; people can (and do) continue talking in video calls when they are a primary interactant at that moment in the call, even when mutual visibility is not sustained. That is, they partake in “open” connections by maintaining verbal participation, even when there is a lack of visibility, while engaging actively in the video call itself. By announcing her forthcoming absence, and then continuing to verbally participate during that temporary absence, Grandma continues her engagement in that call even when she is out of view.

Finally, in this last case, we show how simply through continuing to talk, even while moving out-of-view, interactants can show that they are still participating in a video call. In other words, visual co-presence does not have to be sustained in these “open connection” calls; for temporary leavings, moments of audio-only are sufficient, even without announcements pertaining to these lapses in visibility. In Extract 4 Mom, Stacy (three-and-a-half years old), and Henry (forteen months) are talking to Grandma. Stacy has been telling Grandma what has been going on at preschool. Again, the perspective of the video-recording is from Mom’s desktop computer, while Grandma is talking on her iPad (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. View from Mom’s desktop

Grandma is the sole interactant on her end of the video call, and she goes in and out of view of the video camera several times in this extract. Importantly, during these absences she continues her verbal participation in the video call. Even though she physically moves out of the view of the video camera (and comes back) multiple times, she displays her continued participation by verbally engaging with the remote parties. Importantly, none of the interactants treat her temporary absences as necessitating any sort of pause to the video call, even though she does not announce any of her moments out of view. By continuing to speak while moving out of the camera frame several times, Grandma, as the sole interactant on that end of the call, displays that she is still engaged in the video call.

Extract 4. Fasching

Open in a separate windowHere, Grandma is engaged in other activities while talking with Stacy, Henry, and Mom. She continues talking with them as she moves out of view of the video camera several times. For instance, in line 02, Grandma leaves the view of the camera and continues talking in line 04 and line 07. Again, in line 12, Grandma leaves the view of the camera for a second time, and she still keeps talking with remote parties in line 13. Their conversation about the upcoming holiday of Fasching (which occurs in Germany, where Mom and her children are currently located) between all interactants continues without delay during Grandma’s times of visibility and lack of visibility for her co-interlocutors. Stacy informs her Grandma about the upcoming holiday (line 02), and Grandma responds and asks clarifying questions of both Stacy and Mom about Fasching over several turns, not suspending her verbal participation in the interaction despite at times not being visible. Mom, Stacy, and Henry do not treat Grandma’s lack of visibility in certain moments throughout the call as problematic in any way.

In this interaction, Grandma is the only person on her end of the video call, and is currently actively engaging with her family members on the other end of the call. That is, she is an active interactant in the ongoing conversation, and the sole interactant on her end, so if she left both video and audio range, the interaction would be disrupted. By continuing to speak while moving out of view of the camera, she displays that she is still engaged in participating in the call, even though she may be doing other things at the same time. This case shows how people manage being engaged in interaction when they are not visually present: they can engage in the activity of the video call while not visible and at the same time engage in other non-video-call related activities as long as they continue the verbal interaction. In other words, here the VMC provides the possibility for the always “on” nature of these “open” interactions: there is the assumption that conversation is always possible, as long as verbal communication continues, regardless of the visibility of the interactants.

5. Discussion

Overall, this study shows how mobility, or moving out of view in family video-calls, is an organized activity. We show how people manage the issues of visibility, participation, and multitasking when moving back and forth out of view. Our study reveals how interaction is managed and maintained when one mode of communication within a multimodal communication technology is temporarily not utilized. We show how communication in video calls is normatively organized in “open” connections depending on the interactants’ current engagement (or lack thereof) in the call itself.

We find that there are two different ways in which people leave the view of the video camera during a video call. First, they can be temporarily not visible, and also cease participation in the ongoing call (i.e., they cease verbal communication during their visible absence). In particular, we have shown that when interactants are moving out of view in these instances, they provide reasons and notify remote parties by providing announcements and/or accounts pertaining to their temporary absences. Interactants provide these announcements and/or accounts even when they are not actively engaged in the ongoing call, due to either multiple concurrent involvements (Extract 1), or not being a primary interlocutor at that moment in time (Extract 2), orienting to a necessity to inform their remote co-interactants of their upcoming lack of temporary participation, presumably because if they did not, their leaving may not be noticed by remote parties.

Second, interactants may not be visible but nevertheless still partake in the ongoing call. In these cases, both the interactant who is out of view and their co-interlocutors treat them as ratified and active participants in the video call, even though they are not visible. This shows how, in “open” connections, visibility is not required when audio participation continues during a temporary absence. Notably, in these instances, the “leaver” is actively engaged in the conversation on the call, either they are the primary interactant on their end of the call at that moment (Extract 3) or are the sole interactant (Extract 4). So, by continuing to participate verbally they demonstrate their ongoing engagement in the call, while still being able to engage in other ongoing activities that are taking place not in view of the call itself.

This study adds to our understanding of everyday video calls that remote family members use to keep in touch with each other. By examining the minute details of these video calls, we further Kirk, Sellen, and Cao’s (2010) conception of what an “open” connection looks like in practice in these video calls. We provide further evidence for the fact that these open connections exist: family members do partake in video calls where there are more relaxed norms concerning participation and visibility. As we have shown, visibility is not a requirement for participation in these video calls (e.g., Extracts 3 and 4). However, continued participation in the call depends on current involvements relative to one’s co-present and remote interlocutors. These findings show exactly how family members communicate when using VMC, and how they demonstrate continued participation (or lack thereof) while usingthis channel of communication.

While previous work has studied the accountability of seeing and being seen in video-mediated communication openings (e.g., Ilomäki & Ruusuvuori, 2021; Licoppe & Morel, 2012) and workplace video calls (Oittinen, 2021), our study adds empirical evidence to show how people themselves orient to visibility in ongoing video calls and how they manage their presence of being (not) visible when there is an “open” connection. We have shown how being “not visible” does not necessarily mean being “not available”. It is possible for people to engage in multitasking (e.g., do other activities while participating in video calls). We show how the concept of visibility in VMC is related to continued verbal participation, depending on the engagement of the “leaver” and their remote parties in the call at that time.

Our analysis shows that the issue of visibility is not a stand-alone matter for video-mediated interaction. Instead, it is very much related to the notions of continued participation and multiple concurrent involvements; people orient to visibility differently depending on the interactants’ ongoing involvement in the call. When remote interactants are engaged in multiple concurrent involvements or the “leaver” is not the primary interlocutor in the call (e.g., Extracts 1 and 2), “leavers” announce and/or account for upcoming leavings to mark their temporary lack of availability. However, as Extracts 3 and 4 demonstrate, at times verbal participation alone is sufficient, even with the affordance of visibility in VMC. When “leavers” are the primary or sole interactants in the call, and actively engaged in the ongoing conversation, continued verbal interaction is adequate to demonstrate continued participation. In other words, in video calls, people can demonstrate their engagement not just through the affordance of visibility, but also by maintaining their participation framework (Goodwin & Goodwin, 2004) by continuing to talk.

In today’s global world, families use VMC more than ever before to keep in touch with remote family members. Videoconferencing technologies form part of a “domestic infrastructure”, and have become embedded in the everyday lives of families (Livingstone, 2002, p. 67). In studying two distinct family groups (i.e., migrant families in China and a military family in the US) we have found that families have similar communication practices when engaging in remote VMC: visibility is managed in situ between interactants. As others have shown, participating in video calls has specific relational goals (Harper et al., 2017), but more work is needed to further examine the interactional practices for engaging in these technologies, which will deepen our understanding of everyday family and social life. Family members participate in multiple concurrent activities while engaging in video calls, and future work could examine other ways in which family members utilize these technologies as a part of their everyday lives, adding to our understanding of how families enact family life when remote from each other.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editors of the journal and the anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of our manuscript and their many insightful comments and suggestions.

Funding Sources

This paper is supported by Shanghai Social Science and Philosophy Youth Foundation (No. 2021EXW002).

References

Anderson, C., & Robey, D. (2017). Affordance potency: Explaining the actualization of technology affordances. Information and Organization, 2(27), 100–115. DOI: 10.1016/j.infoandorg.2017.03.002

Arminen, I., Licoppe, C. & Spagnolli, A. (2016). Respecifying mediated interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 49(4), 290-309. DOI: 10.1080/08351813.2016.1234614

Baldassar, L., Nedelcu, M., Merla, L., & Wilding, R. (2016). ICT-based co-presence in transnational families and communities: Challenging the premise of face-to-face proximity in sustaining relationships. Global Networks, 16(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12108

Beach, W. A. (1993). Transitional regularities for ‘casual’ “okay” usages. Journal of Pragmatics, 19(4),325-352. DOI: 10.1016/0378-2166(93)90092-4

Beck, U., & Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2014). Distant Love: Personal Life in the Global Age. Polity Press.

Brubaker, J. R., Venolia, G., & Tang, J. C. (2012). Focusing on shared experiences: Moving beyond the camera in video communication. In Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference (pp. 96–105). New York: ACM. DOI: 10.1145/2317956.2317973

Cabalquinto, E. C. B. (2018). “We’re not only here, but we’re there in spirit”: Asymmetrical mobile intimacy and the transnational Filipino family. Mobile Media & Communication, 6(1), 37-52.

Castles, S, de Haas, H., & Miller, M. J. (2014). The Age of Migration (Fifth Edition). Palgrave Macmillan.

DiDomenico, S. & Boase, J. (2012). Bringing mobiles into the conversation: Applying a Conversation Analytic approach to the study of mobiles in co-present interaction. In Tannen, D. & Trester, A. M. (Eds.), Discourse 2.0: Language and New Media (pp. 119-132). Georgetown University Press.

DiDomenico, S. M., Raclaw, J., & Robles, J. S. (2018). Attending to the mobile text summons: Managing multiple communicative activities across physically copresent and technologically mediated interpersonal nteractions. Communication Research, 47(5), 669-700. DOI: 10.1177/0093650218803537

Drew, P., & Chilton, K. (2000). Calling just to keep in touch: Regular and habitualised telephone calls as an environment for small talk. In Coupland, J. (Ed.), Small Talk (pp. 137-162). Longman.

Due, B. L., & Lange, S. B. (2021). Body part highlighting: Exploring two types of embodied practices in two sub-types of showing sequences in video-mediated consultations. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 3(3), DOI: 10.7146/si.v3i3.122250

Due, B. L., & Licoppe, C. (2021). Video-mediated interaction (VMI): Introduction to a special issue on the multimodal accomplishment of VMI institutional activities. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 3(3), https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v3i3.123836

Fox, J., & McEwan, B. (2017). Distinguishing technologies for social interaction: The perceived social affordances of communication channels scale. Communication Monographs, 84(3), 298-318.

Gan, Y., Greiffenhagen, C., & Reeves, S. (2020). Connecting distributed families: Camera work for three-party mobile video calls. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-12). New York: ACM. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376704

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in Ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Gibson, J. (1977).The theory of affordances. In Shaw, R., and Bransford, J. (eds.). Perceiving, acting, and knowing:Toward an ecology psychology (pp. 67-82). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Goffman, E. (1963). Behavior in Public Places: Notes on the Social Organization of Gatherings. The Free Press.

Goodwin, C. (1987). Unilateral departure. In Button, G., & Lee, J. (eds.). Talk and Social Organization (pp. 206-216). Multilingual Matters.

Goodwin, C., & Goodwin, M. H. (2004). Participation. In A Companion to Linguistic Anthropology (pp. 222–244). John Wiley & Sons.

Hamwey, M. K., Rolan, E.P., Jensen, A.C., Whiteman, S. D. (2019). “Absence makes the heart grow fonder”: A qualitative examination of sibling relationships during emerging adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(8), 2487-2506.

Harper, R., Rintel, S., Watson, R., & O’Hara, K. (2017). The “interrogative gaze”: Making video calling and messaging “accountable”. Pragmatics, 27(3), 319-350. DOI: 10.1075/prag.27.3.02har

Harper, R, Watson, R., & Licoppe, C. (2017). Interpersonal video communication as a site of human sociality: A special issue of Pragmatics. Pragmatics, 27(3), 301-318.

Heath, C., & Luff, P. (1992). Media space and communicative asymmetries: Preliminary observations of video-mediated interaction. Human–Computer Interaction, 7(3), 315–346. DOI: 10.1207/s15327051hci0703_3

Hepburn, A., & Bolden, G. B. (2017). Transcribing for Social Research. Sage.

Hjulstad, J. (2016). Practices of organizing built space in videoconference-mediated interactions. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 49(4), 325-341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2016.1199087

Hollan, J., & Stornetta, S. (1992). Beyond being there. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 119–125). ACM.

Hutchby, I. (2001). Technologies, texts, and affordance. Sociology, 45(2), 441-456. DOI: 10.1177/S0038038501000219

Ilomäki, S., & Ruusuvuori, J. (2021). From appearings to disengagements: Openings and closings in video-mediated tele-homecare encounters. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 3(3), DOI: 10.7146/si.v3i3.122711

Kenyon, S. (2010). What do we mean by multitasking? Exploring the need for methodological clarification in time use research. International Journal of Time Use Research, 7(1), 42–60. DOI: 10.13085/eIJTUR.7.1.42-60

Kidwell, M., & Zimmerman, D. H. (2007). Joint attention as action. Journal of Pragmatics, 39(3), 592-611.

Kirk, D. S., Sellen, A., & Cao, X. (2010). Home video communication: mediating “closeness”. In Proceedings of the 2010 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (pp. 135-144). ACM. DOI: 10.1145/1718918.1718945

Licoppe, C. (2004). ‘Connected’ presence: The emergence of a new repertoire for managing social relationships in a changing communication technoscape. Environment and planning D: Society and space, 22(1), 135-156.

Licoppe, C. (2017a). Showing objects in Skype video-mediated conversations: From showing gestures to showing sequences. Journal of Pragmatics, 110, 63-82. DOI: 10.1016/j.pragma.2017.01.007

Licoppe, C. (2017b). Skype appearances, multiple greetings, and “coucou”: The sequential organization of video-mediated conversation openings. Pragmatics, 27(3), 351-386. DOI: 10.1075/prag.27.3.03lic

Licoppe, C., & Morel, J. (2012). Video-in-interaction: “Talking heads” and the multimodal organization of mobile and Skype video calls. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 45(4), 399-429. DOI: 10.1080/08351813.2012.724996

Licoppe, C. & Morel, J. (2014). Mundane video directors in interaction: Showing one’s environment in Skype and mobile video calls. In M. Broth et al. (Eds.) Studies of Video Practices (pp. 143-168). Routledge.

Licoppe, C., & Tuncer, S. (2014). Attending to a summons and putting other activities “on hold”, In P.T. Haddington, L. Keisanen, , L. Mondada and M. Nevile (Eds.), Multiactivity in Social Interaction (pp. 167-190).John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Lim, S. S., Bork-Hüffer, T., & Yeoh, B. S. (2016). Mobility, migration and new media: Maneuvering through physical, digital and liminal spaces. New Media & Society, 18(10), 2147–2154.

Livingstone, S. (2002) Young People and New Media: Childhood and the Changing Media Environment. Sage.

Madianou, M., & Miller, D. (2012). Migration and New Media: Transnational Families and Polymedia. Routledge.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Mondada, L. (2014). Conventions for multimodal transcription. Retrieved from https://franz.unibas.ch/fileadmin/franz/user_upload/redaktion/Mondada_conv_multimodality.pdf.

Neustaedter, C., & Greenberg, S. (2011). Intimacy in long-distance relationships over video calling. Research Report. Department of Computer Science. University of Calgary, Canada.

Nielsen, M. F. (2019). Adjusting or verbalizing visuals in ICT-mediated professional encounters. In D. Day & J. Wagner (Eds.), Objects, Bodies and Work Practice. Multilingual Matters.

Oittinen, T. (2021). Noticing-prefaced recoveries of the interactional space in a video-mediated business meeting. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 3(3), DOI: 10.7146/si.v3i3.122781

Pomerantz, A. (1984). Pursuing a response. In J. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis (pp. 57-101). Cambridge University Press.

Raymond, G., & Lerner, G. H. (2014). A body and its involvements. In Haddington, P, T. Keisanen, L. Mondada and M. Nevile (eds), 2014. Multiactivity in Social Interaction (pp. . 227-245). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Rintel, S. (2013). Video calling in long-distance relationships: The opportunistic use of audio/video distortions as a relational resource. The Electronic Journal of Communication/La Revue Electronic de Communication (EJC/REC), 23.

Rosenbaum, L., Rafaeli, S., & Kirzon, D. (2016). Participation frameworks in multiparty video chats across cross-modal exchanges in public Google hangouts. Journal of Pragmatics, 94, 29-46.

Searles, D. K. (2018). Look it Daddy’: Shows in family Facetime calls. Research on Children and Social Interaction, 2(1), 98-119. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1558/rcsi.32576

Sidnell, J., & Stivers, T. (2013). The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Wiley-Blackwell.

Zouinar, M., & Velkovksa, J. (2017). Talking about things: Image-based topical talk and intimacy in video-mediated family communication. Pragmatics, 27(3), 387-418. doi 10.1075/prag.27.3.04zou

* Corresponding author: Yumei Gan (Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China). Email: yumei.gan@sjtu.edu.cn↩

1 We acknowledge that there are some distinctive features of the two datasets. For example, the emotional stakes in the two corpora appear to be different: the Chinese data includes parent-child separation while the American data is mostly about child-grandparent separation (with some calls with parent-child separation). However, we combined the two corpora for two main reasons. First, we find that in both corpora interactants react to (in)visibility on the screen in similar ways. We examine members’ methods (Garfinkel, 1967) to manage these moments of (in)visibility, and the combination of two corpora strengthens our analysis. Second, we find that in both corpora (regardless of device use), people orient to people moving out of view. This mixture of stationary and mobile devices in our data set allows us to focus on the issue of “visibility” in VMC—how visibility is managed with different technological devices.↩

2 Note that Grandma’s self-repair from Pep-Pepper to then Gracie appears to be a self-repair from the name of her prior (presumably deceased) dog to the name of her current dog.↩

3 In Chinese culture, one parent would tease a child as “greedy” when the child eats a lot or if the child eats something outside of mealtime. In this family video call, the grandparents also said that Jia is greedy because she eats too much.↩