Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Mundane Food Photography:

Managing Multiple Involvements in the Context of Self-Initiated Smartphone Use

Iuliia Avgustis1 & Florence Oloff1,2

1University of Oulu

2Leibniz-Institut für Deutsche Sprache

Abstract

This article investigates mundane photo taking practices with personal mobile devices in the co-presence of others, as well as “divergent” self-initiated smartphone use, thereby exploring the impact of everyday technologies on social interaction. Utilizing multimodal conversation analysis, we examined sequences in which young adults take pictures of food and drinks in restaurants and cafés. Although everyday interactions are abundant in opportunities for accomplishing food photography as a side activity, our data show that taking pictures is also often prioritized over other activities. Through a detailed sequential analysis of video recordings and dynamic screen captures of mobile devices, we illustrate how photographers orient to the momentary opportunities for and relevance of photo taking, that is, how they systematically organize their photographing with respect to the ongoing social encounter and the (projected) changes in the material environment. We investigate how the participants multimodally negotiate the “mainness” and “sideness” (Mondada, 2014) of situated food photography and describe some particular features of participants’ conduct in moments of mundane multiactivity.

Keywords: conversation analysis, multimodality, multiactivity, smartphone use, food photography

1. Introduction

Taking pictures of food with personal mobile devices is a very common activity, observable both in public settings and in the increasing number of food-related photographs published on social networks. Despite a growing interest in situated mobile device use and its social implications, research on everyday photographic practices in the digital age is still scarce (e.g., Weilenmann & Hillmann, 2019; Weilenmann et al., 2013). In this paper, we investigate mundane photography practices in cafés and restaurants, thereby contributing to the interactional study of the situated production of pictures (Tekin, 2017). More specifically, we have selected sequences in which participants take pictures of food or drinks during restaurant visits with friends in Russia. Prepared drinks and meals represent a particular type of photographic object, as they are available for photographic activity only for a certain period of time (e.g., after the food has been served and before it will be eaten). Based on video recorded encounters and screen captures of mobile devices, we illustrate how participants orient to these “photographables” (Mondada et al., 2020) and time the taking of a picture with respect to the sequential development of the ongoing encounter.

By considering how and when picture taking is initiated and carried out, we underline the complexity of this ostensibly mundane and simple activity. This also allows for reflections on how individual smartphone use is introduced and accounted for in an ongoing social encounter, how photographers and their co-participants establish certain items as aesthetically relevant objects, and how the photographing activity then sequentially unfolds. Our analyses contribute more generally to the exploration of situated mobile device use as part of mundane multiactivity (Haddington et al., 2014). In what follows, we first review interactional studies on mobile device use in face-to-face encounters and research concerning photography practices (1.1–1.2). After a short presentation of the data (2.), we analyze two examples where food photography is accomplished as a non-prioritized, embodied activity (3.). We then analyze two cases that demonstrate how participants can temporarily prioritize food photography and suspend other ongoing activities (4.). Although in all excerpts there is only one participant who initiates food photography, the way this activity unfolds is collaboratively and multimodally negotiated by all co-present participants.

1.1. The organizational and moral dimension of mobile device use in co-presence

Mobile technologies have become interwoven with everyday activities and social action in both mundane (Brown et al., 2013, 2015; McMillan et al., 2015) and institutional settings (Asplund et al., 2018; Sahlström et al., 2019). This line of interactional research has shown how mobile device use contributes to the organization of social action (Hellerman et al., 2017; Raclaw et al., 2016), with a frequent focus on the simultaneous management of multiple involvements (DiDomenico & Boase, 2013). The conceptual toolkit for analyzing this aspect of interaction was first borrowed from Goffman’s (1963) work on different types of involvements. Goffman defined main involvement as the “one that absorbs a major part of an individual’s attention and interest, visibly forming the principal current determinant of his actions” and side involvement as “an activity that an individual can carry on in an abstracted fashion without threatening or confusing simultaneous maintenance of a main involvement” (1963, p. 43). In research on mobile device use in face-to-face interactions, the cognitivist underpinnings of these notions were replaced by analyses of participants’ practices (e.g., DiDomenico & Boase, 2013; Oloff, 2019; Relieu, 2008). If the mobile device use is not directly related to the ongoing interaction (“divergent use”, Brown et al., 2013), it is usually analyzed as a side/secondary involvement (e.g., in phone-related activity) that interweaves with the main/primary involvement (e.g., in the conversation with co-present others).

These different understandings of interactional involvement were further developed in studies on multiactivity (Haddington et al., 2014), in which researchers focused on practices that participants employ to display their recognizable involvement in several courses of action. Following this approach, we focus on the way participants adjust their actions and accountably (i.e., through visible and audible means) prioritize one activity over another. We also use the notions of “mainness” and “sideness” (Mondada, 2014) to show the negotiated character of this situated prioritization. “Main” and “side” activities are, therefore, treated as situated achievements rather than predefined characteristics of specific types of activities as Goffman (1963) suggested. As detailed analysis of multiactivity settings shows, mainness and sideness of different activities are “made relevant locally and contingently” (Mondada, 2014, p. 70), and this situated hierarchization is collaboratively produced by participants (Licoppe & Tuncer, 2014, p. 180). Much like other activities, mobile device use can also be displayed and oriented to as a main/primary activity in everyday face-to-face encounters, such as when a participant receives a text message and visibly deals with it (DiDomenico et al., 2018).

Many existing studies on multiple involvements/multiactivity in the context of mobile device use focus either on the management of parallel (co-present and phone-mediated) conversations or on the management of multiple involvements after the occurrence of a summons (DiDomenico & Boase, 2013; DiDomenico et al., 2018; Licoppe & Tuncer, 2014; Relieu, 2008). If summoned by an audible alert on their mobile device, participants switch from their main involvement, the conversation, to using their mobile phone as soon as the current sequential development and participation frameworks allow for an unproblematic suspension of their involvement in the co-present activity (DiDomenico & Boase, 2013; DiDomenico et al., 2018). While these studies are particularly interested in the fact that mobile-generated summons can pressure participants into using their devices, other external events can also create opportunities for mobile device use, such as a traffic light turning red, allowing commuters the opportunity to use their phone (Licoppe & Figeac, 2018). Thus, the timing and kind of mobile device use is contingent on both the temporal dynamics of the ongoing activity and the ecology of the material setting.

Self-initiated mobile device use has attracted less attention from researchers (Oloff, 2021), with many existing studies focusing on convergent device use, wherein the relevancy for its use emerges from the ongoing talk (Brown et al., 2013). These avenues of research have shown how a digital device can be used as an additional semiotic resource and as a resource for the production of social action (Aaltonen et al., 2014; Greer, 2016; Raclaw et al., 2016). The management of multiple involvements (in different activities) in the context of divergent self-initiated smartphone use for purposes other than communication with distant others has not yet been systematically explored. Our study contributes to this endeavor by showing how a participant’s self-initiated food photographing activity is related to the dynamics of the ongoing encounter, their co-participants’ conduct, and to changing features of the setting (such as the arrival of food).

The question of how co-participants respond to and manage others’ smartphone use is also connected to the topic of morality. In the early days of the mobile device era, researchers were particularly interested in the way cell phone use (answering calls and messaging) affected the moral order in public spaces (e.g., Murtagh, 2002; Paragas, 2005). Nowadays, smartphones have evolved a wider set of functionalities that can also be used for a variety of not necessarily solitary activities (taking or showing pictures, searching for information, or listening to music together). More recent studies on the morality of smartphone use in private face-to-face interactions (e.g., Mantere & Raudaskoski, 2017; Robles et al., 2018) have argued that participants systematically orient to the accountability of technology use. Actions with and on the phone are often opaque and therefore not always recognizable for co-present participants, and smartphone users have a variety of ways to make these actions accountable to others (Porcheron et al., 2016; Suderland, 2020). Due to the repositioning and manipulation of the smartphone before and while taking a picture, smartphone photography is a potentially recognizable technology-related activity (as compared to surfing the web or checking messages). However, it does involve other concerns of opacity, such as who or what will figure in the picture, or why the smartphone holder is taking a picture at this moment. Mundane photographic practices in co-presence, therefore, provide an apt setting for further exploring both the accountability and the sequential organization of everyday technology use.

1.2. Photography as a social, situated, and embodied practice

Mundane photographic practices have been studied earlier, albeit mostly through ethnographic and descriptive approaches (e.g., Chalfen, 1987). The transition from analogue to digital photography has led to a shift from the recording of past events and places to a focus on the present moment and place, allowing for increasingly casual and social photographing practices (Larsen, 2008; Oksmann, 2006). In their study on Instagrammers visiting a museum of natural history, Weilenmann et al. (2013) investigated how and why participants chose, edited, and shared specific photos. The physical walking paths within museums or zoos displayed the photographers’ orientation to their online audience on social media channels (Hillmann & Weilenmann, 2015). These “social media trajectories,” captured through a combination of interviews, participant observation, GPS tracking, and video documentation, provide a glimpse of situated, embodied curating and digital narrative practices (Wargo, 2015). In their study of selfie photography, Weilenmann and Hillman (2019) adopted a more explicit focus on the embodied practice of picture taking. They observed how participants alternate between different photographic motives, postures, techniques, and devices, noting that phones are used for co-present collaborative interaction, even when the activity (such as taking a selfie) is seemingly individualistic (2019, p. 13). While this research underlines the relevance of exploring the details of situated photographing practices, studies using a full videographic approach in natural settings and producing detailed sequential analyses are still rare. Some recent multimodal studies have been interested in photography as a professional practice that involves the participants’ public bodily arrangement and negotiation of poses through the photographer’s professional vision, touch, and instructions (Mondada & Tekin, 2020; Tekin, 2017). Our analysis contributes to this latter line of research by focusing on multimodal and sequential details of mundane photographic practices in co-presence with others.

The massive representation of mundane experiences in digital photography could be simply understood as a “machinery for banality” (Koskinen, 2006), enriching the users’ interpersonal communication processes. More recent studies draw a more nuanced picture and acknowledge the emergence of “creative vernaculars” (Berry, 2015) that can be studied as ongoing processes visible in the production, curation, and sharing of pictures in online repositories. Studies of digital food cultures (e.g., on Twitter, Zappavigna, 2014, or food blogs, de Solier, 2018) have shown that food photography does not only fulfil an aesthetic and illustrative function but is also exploited by social media users for the actual preparation of food, for constructing personal narratives and identities, and for communicating and sustaining social relationships. Within conversation analytic studies, eating and other food-related activities have been traditionally analyzed as an offline activity providing a setting for talk-in-interaction (e.g., Goodwin, 1997), for socialization processes within the family (e.g., Ochs & Shohet, 2006), or, more recently, as related to embodiment and the social and negotiable nature of sensorial experiences (e.g., Mondada, 2009, 2021; Wiggins, 2013). This last line of research particularly illustrates that the consumption of food is closely intertwined with the sequentiality of talk. In this paper, we adopt a similar focus by considering how the presence of food and drinks can lead to the use of mobile devices and how this is linked to the sequential structure of ongoing talk. Moreover, as analyses of mundane digital photography and its aesthetics are mainly based on the finished visual product and interviews with participants, our study of photographic practices also allows for the exploration of participants’ situated aesthetic choices.

2. Data and method

The data set used in this article was collected between 2018 and 2020 and consists of nine video recordings of naturally occurring encounters among friends and fellow students (aged 19–25, with 2–4 participants per encounter), all of whom are native Russian speakers. The recordings were made at a café or restaurant of the participants’ choice, with the duration of the encounters varying from one and a half to two hours. Participation was informed and voluntary, and all participants gave their consent to the use of unaltered screen captures and video fragments in publications. While the participants were informed about the researchers’ interest in both everyday interaction and smartphone use, they did not receive any instructions with respect to their mobile device use, meaning that this was not a prerequisite for the recording. Instances of participants taking pictures of food or drinks were found in four recorded interactions, leading to a collection of twenty-one cases. For the sake of brevity, in this paper all these cases are referred to as food photography. The collection includes ten cases of food photography initiated as a side activity and eleven cases of food photography initiated as the main activity.

Depending on the setting and number of participants, one or several cameras were used to capture the overall encounter. Additionally, all participants were equipped with small wearable cameras and screen capturing software (turned on once at the beginning of the encounter and left to run continuously) was used for each mobile device whenever technically possible. In previous studies on smartphone use, complex recording setups have proven useful for understanding the temporal and sequential organization of smartphone use from the participants’ perspectives (Asplund et al., 2018; Avgustis & Oloff, forthcoming; Hellermann et al., 2017; Sahlström et al., 2019). The importance of recording individual activities (such as device manipulation) for the purpose of EMCA analysis has also been emphasized (Mondada, 2013). Recordings from wearable cameras and screen capture recordings in combination with recordings from a static camera allow the researcher to analyze how on-screen events affect the smartphone user’s course of action and, potentially, the progressivity of the interaction in general. It is, however, important to remember that this recording set-up occasionally provides the researcher with visual access to the smartphone user’s individual activity, which might not be observable for their co-present participants. Therefore, when analyzing these data, we took into consideration that the smartphone user’s co-present others might not have been aware of the ongoing on-screen activity or its current state unless these were made recognizable by the smartphone user themselves (see also Avgustis & Oloff, forthcoming, on “participant opacity” and Raudaskoski et al., 2017, on “bystander ignorance”).

While participants occasionally oriented to the recording equipment (primarily for the purpose of picture taking) or topicalized it, we did not find any evidence of these orientations in the data presented in the paper. Moreover, these occasional orientations, which are also common in less advanced recording set-ups, do not “contaminate” the whole data set (Heath et al., 2010, p. 48).

In the video fragments presented below, camera angles were selected according to their relevance for the analysis. The data extracts were transcribed according to the Jeffersonian system (Jefferson, 2004), along with Bolden’s (2004) transliteration system to represent the original talk in Russian. As audible action was transcribed based on several audio sources, some features of the talk might not be heard in the video fragments. Embodied conduct was transcribed according to Mondada’s (2018, 2022) conventions and analyzed using the method of multimodal interaction analysis (e.g., Deppermann & Streeck, 2018; Mondada, 2007; Streeck et al., 2011). All participants were given pseudonyms, and any other personal data were anonymized in the transcripts, screen captures, and video fragments.

3. Accomplishing food photography as a side activity

In the first part of the analysis, we present two cases of our first subcollection (ten cases), in which one of the participants initiates food photography without a significant effect on the already ongoing or emerging activities. The sideness or mainness of this newly emerged activity is then multimodally negotiated and accomplished by all co-present participants, and the character of photo taking as a “non-conflicting” activity is collaboratively achieved. We show that this type of picture taking is well timed with respect to the sequential development of the ongoing conversation. More specifically, we demonstrate that the timing and multimodal framing of an individual engagement in picture making is sensitive to the current participation framework, that is, the photographer’s rights, obligations, and opportunities to get involved as a speaker or recipient in the ongoing conversation.

Our first excerpt exemplifies how food photography can be accomplished as a side activity in a dyadic encounter. The object of photography is the glass of white wine which one of the participants receives four and a half minutes before the beginning of the excerpt. During this time, both participants take a sip of the wine and discuss its taste characteristics but have not yet photographed it. Prior to the excerpt, Maria (MAR) and Ekaterina (EKA), who are both graphic design students, discuss the design of the restaurant menu. After listening to Maria’s comments regarding the appearance of the menu, Ekaterina states that Maria’s suggestions do not relate to the redesign of the menu, but rather to its reprinting (lines 01–02). Ekaterina then initiates a new solitary activity, and Maria uses this “opportunity slot” to take a photo of her glass of wine.

Excerpt 1. Wine

Open in a separate window

Just after replying to Maria’s comments regarding the menu, Ekaterina starts to bend down (line 03). It later becomes evident that she is attempting to get a gift for Maria out of her bag (line 09). Maria, who has been flipping through the menu and gazing down at it since the beginning of the excerpt, then agrees with Ekaterina and quickly glances at her (line 04, Figure 2). She can, therefore, perceive Ekaterina’s new involvement (her body posture and the lack of gaze orientation). A short lapse (1.5 sec., line 05) passes, during which Maria directs her gaze towards the glass of wine (Figure 3). At this moment, the glass of wine, which has been located on the table for more than four minutes, is noticed as an object worthy of being photographed, and Maria almost immediately starts to reach for the phone on her right (Figure 4, line 06). The aesthetic value of this drink is, therefore, noticed not when the drink is served but when a “suitable” sequential slot for photo-taking arises (no ongoing talk, no gaze orientation from a co-participant, no ongoing mutual involvements).

As Maria initiates this new activity, Ekaterina quickly glances at her and adds one more mocking comment related to their previous discussion about the menu (line 06). Maria responds with a laughter particle while taking up her phone (line 07). While a phone call would normally be introduced with a preface, which projects the new activity and change of involvement (Rae, 2001; Oloff, 2021), food photography can be accomplished as a silent embodied activity (Mondada, 2018). As verbal resources are often not required to carry out food photography, the potential of accomplishing it as a side or non-competing activity is higher than in the case of, for instance, phone calls. The sideness of Maria’s activity is also afforded by the embodied participation framework (Goodwin, 2007), as Ekaterina bodily disengages and initiates another, potentially individual, activity after the discussion about the menu has reached its possible conclusion.

Another lapse emerges (line 08), during which Maria frames the wine glass and moves Ekaterina’s phone out of the frame (Figure 5). While Maria is involved in her individual activity, Ekaterina takes the gift out of the bag and introduces it with an utterance about Father Frost, a mythical character who serves as a counterpart of Santa Claus in Russia (line 09). After also verbally introducing the new activity, Ekaterina looks at Maria and perceives her involvement in a different activity. This involvement is recognizable via Maria’s photographer posture: the phone is raised and held with both hands, the camera faces the object, and the photographer looks at the object through the smartphone’s screen (Figure 6). Other photography-related postures have previously been discussed in the context of professionals taking photos of models/clients (e.g., Mondada & Tekin, 2020, on perspectival posture) and in the context of selfies (Weilenmann & Hillman, 2019). While these postures are seemingly routinized (Streeck, 2018), their recognition is context-sensitive and depends, for example, on the co-participant’s visual access to the object of photography. In this case, the “photographer posture” also has an interactional significance, as it indicates the smartphone user’s involvement in a specific activity over a certain period of time.

In what follows, the sideness of this photography activity is collaboratively achieved by both participants. After accountably initiating a next action and, thereby, a new activity, Ekaterina puts the gift on the table and briefly monitors Maria’s conduct. Maria then promptly responds to Ekaterina while simultaneously taking a picture (line 11, Figure 7a/b). By allocating her linguistic and body resources to these two different activities (taking a picture and answering Ekaterina), Maria displays her dual involvement (Raymond & Lerner, 2014). She promptly provides a relevant response to Ekaterina and immediately puts her phone away after taking a picture, which indicates a situated prioritization of the newly emerged joint activity over the individual side activity. Ekaterina then moves the gift towards Maria (Figure 8), and both participants engage in a new joint activity. Food photography is, therefore, both designed as a side activity by Maria and oriented to as such by Ekaterina.

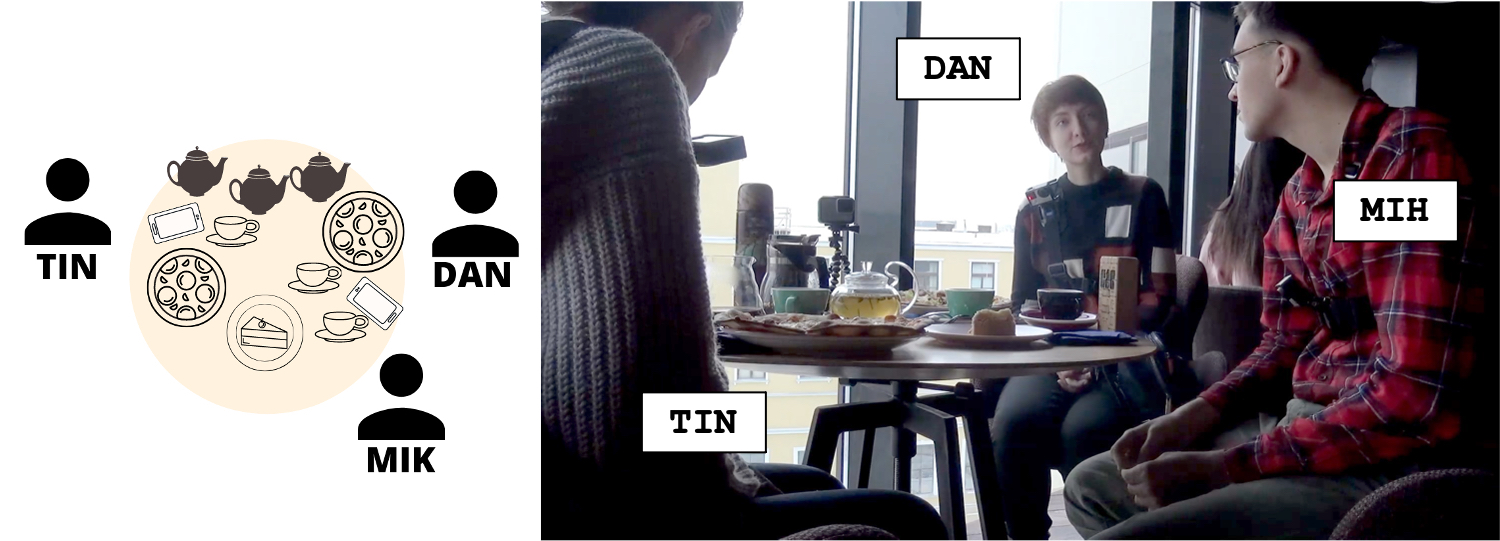

While in the first excerpt food photography was initiated during a lapse that emerged after a topic was closed, it is not the only situation in which food photography can be initiated as a side activity. The following excerpt illustrates how picture taking can be accomplished as a side activity in a multi-party interaction, in which the photographer’s co-participants are involved in a discussion before, during, and after picture taking. In this excerpt, the activity is neither commented on by the photographing participant, Tina (TIN), nor is it acknowledged or participated in by her co-participants Dana (DAN) and Mikhail (MIK). Prior to the excerpt, the three participants have been complaining about a university project they are all working on. Approximately 30 seconds before the excerpt begins, a waitress brings two pizzas for Dana and Tina, but Mikhail is still waiting for his main dish (the teapots and cheesecake on the table were brought earlier). Figure 9 shows the seating arrangement of the participants and the different objects on the table.

Figure 9. The seating arrangement of the participants and the different objects on the table

As the participants rearrange the food and cutlery on the table, they continue discussing their work project. While Dana is developing a multi-unit turn about her attempt to leave the project and Mikhail is responding to her, Tina takes a picture of the pizza in front of her.

Excerpt 2. Pizza

Open in a separate window

As she speaks, Dana is looking at Mikhail (line 01), who then displays his recipiency by responding and shifting his gaze to her (line 02), so that they engage in a mutual gaze during her next turn-constructional units (lines 01–05). Meanwhile, Tina is arranging the cutlery on the table. When she is about to finish this activity, she looks up to Dana twice (line 03) and then leans back on her chair, displaying engagement and recipiency through her body and gaze orientation (Goodwin, 1981; Heath 1982, 1984). She can now perceive that Dana and Mikhail are looking at each other during the next three seconds while Tina is maintaining her orientation (lines 03-04; Figure 10a/b). Finding herself on the periphery of the embodied participation framework (Goodwin, 2007), Tina withdraws her gaze from her co-participants and starts looking at her smartphone, which she then picks up with her left hand (line 04). Just as in the previous excerpt, the embodied participation framework provides Tina with an opportunity to initiate a new side activity that does not compete with already ongoing activities. Tina first lifts the phone slightly and checks the display, then adjusts its brightness (line 05), and finally opens the camera app (Figure 11a/b), which is precisely timed with respect to a transition-relevance place (TRP) in Dana’s turn (lines 06–08).

After activating the camera app, Tina starts lifting her phone with both hands and shifts her posture (lines 08–09). At the next TRP in Mikhail’s turn (after dosvidos, line 08), she quickly glances first at the table and pizza in front of her, then at Dana, who, at this moment, is looking down at the table (Figure 12a/b). Previous research has shown that speakers can select all co-participants as addressees by alternating their gaze between them (Auer, 2018; Rühlemann et al., 2019), but in this excerpt, the current speaker’s gaze is oriented exclusively towards Mikhail. Dana, therefore, does not seem to pursue an answer from Tina as a possible second recipient of her multi-unit turn at that moment. Tina, who during her gaze shift (line 09) had slightly opened her mouth in a possible turn-preparative move, closes her mouth again, gazes back down at her smartphone display and re-engages in her solitary smartphone use.

When Mikhail starts elaborating on his own planning problems related to the university project (line 11), Tina begins to move the smartphone and her upper body to adjust the image section with respect to the pizza in front of her (lines 11–13; Figure 13a/b). She then modifies the frame four times to gradually exclude Dana’s body from the picture (Figure 14–16) without asking her to move and possibly affecting the ongoing conversation. The new current speaker (lines 11–13), Mikhail, does not attempt to secure Tina’s gaze either. As Goodwin (1981) showed, speakers can rely on restarts, pauses, and hesitations to achieve a state of mutual gaze. As this is not attempted here, we can assume that Tina’s smartphone use and her temporary disengagement are not treated as problematic. Both Dana and Mikhail continue their current activity, thus orienting to Tina’s new activity as an individual side activity. After selecting a more balanced image composition (line 13; Figure 17a/b), Tina finally takes a picture. She then immediately closes the camera app and puts the phone back on the table, so that her phone use has been visibly completed at the end of Mikhail’s turn (line 14). At the next TRP, Tina responds to Mikhail’s previous turn (lines 15–16, Dana quickly drops out of her turn) and to the overall topic (see also her gaze to Dana, Figure 18), displaying that she has monitored both the content and development of Mikhail’s turn while taking the picture.

This excerpt again shows that an individual involvement in the activity of picture taking is coordinated with the ongoing conversation. Tina starts manipulating her phone only after perceiving that her co-participants are engaged in mutual gaze and talk and finding herself on the periphery of this embodied participation framework. Her first attempt to self-select, the picture taking, and her final self-selection are finely adjusted to the sequential and topical development of the conversation (for example, her fitted response in line 16). Notice that Tina does not announce or formulate a verbal account of her phone use: Dana and Mikhail are mutually oriented to each other (not to Tina), the type of phone use is visible in Tina’s embodied conduct, and she also visibly excludes her co-participant’s body from the final image section. As neither Dana nor Mikhail display that they attend to this in any way, picture taking is jointly accomplished as one participant’s side activity, not affecting the progressivity of other ongoing activities.

This section shows that “opportunity slots” for the unproblematic accomplishment of self-initiated smartphone use as a side activity emerge in both dyadic and multi-party encounters. Picture taking does not necessarily occur just after food is served, but it can occur later in a suitable sequential slot, such as when the photographer finds themself on the periphery of the embodied participation framework. In both cases, picture taking is not oriented to as problematic or explicitly accounted for, but it is instead accomplished in a way that makes this activity accountable to others. The sideness of food photography is collaboratively achieved by all the participants, who design this activity and allow it to unfold in a way that does not interfere with the progressivity of other, already ongoing, actions. In the next section, we show that, besides “opportunity slots,” participants also orient to projectable changes in the material environment (specifically, the object of photography), which can make picture taking a relevant activity at a particular moment.

4. Accomplishing food photography as the main activity

We now present two excerpts in which the same participants from the previous examples (Maria and Tina) design food photography as a temporarily prioritized activity, that is, they jointly treat it as the main activity. Food photography can be accomplished as one participant’s individual activity and oriented to as such by others (as in Excerpts 1 and 2), or it can temporarily become the main activity for all participants. We demonstrate how participants accountably orient to the properties of the object for photography when initiating picture taking in such a sequential environment. As the aesthetic value of the food is bound to decline at some point during the encounter (usually because it will be cut up, mixed, and ultimately eaten), participants often initiate photo taking when its aesthetic aspect is “threatened.” In this case, a photographer can prioritize picture taking and suspend the activity-in-progress, treating picture taking as a more relevant activity in this moment.

Excerpt 3 shows how participants in face-to-face encounters collaboratively achieve the mainness of self-initiated smartphone use. Ekaterina (EKA) and Maria (MAR) are sitting in a café tackling, among other topics, various university-related complainables. Ekaterina has been telling stories about a specific university lecturer for several minutes before the excerpt starts. A few minutes earlier, the waiter brings two bowls of soup, and Ekaterina begins eating. Maria at first prepares to eat as well but then picks up her phone (line 02) and takes a picture of the soup. Unlike in the previous cases (Ex. 1 & 2), taking a picture is preceded by a turn-at-talk of the smartphone user: in this case, an assessment of what the food looks like (line 04).

Excerpt 3. Pumpkin soup

Open in a separate windowAlthough the participants receive their soup about nine minutes before, Maria has not yet started eating it as she still has a first course to finish. Just prior to the excerpt, she has asked for and taken a spoon from the cutlery receptacle to Ekaterina’s left. Maria’s eating preparations are well-timed with a point of possible completion in Ekaterina’s multi-unit turn, which is the end of her report of a fellow student’s assessment of the lecturer in question (of which line 2 represents the last part). It is also now – when approaching the spoon and gazing down (for one second, line 01) – that Maria can assess the soup’s visual features more thoroughly. After hovering the spoon over the soup, Maria then retracts it to avoid ruining its aesthetic aspect. During Ekaterina’s utterance (line 02), Maria transfers the spoon to her left hand, thereby freeing her right hand to access her phone (Figures 19–20). This preparation in the pre-beginning position (Mondada, 2007) leads to her seizing the phone at a moment when some alignment and affiliation to Ekaterina’s complaint would be due. Thus, Maria’s following positive assessment of the soup (“heck this is a piece of art,” line 04) fills the prospective response slot while at the same time displays that she is orienting to food photography as her main activity at that moment. It cannot, however, be categorized as a blatant disattending (Mandelbaum, 1991) of Ekaterina’s “third-party” complaint, as it is attended to later, after the picture taking activity is finished (line 10).

After the possible completion point of her turn and the ensuing gap (lines 02–03), Ekaterina keeps gazing down (still adding some rice to her soup), audibly swallows (line 03), and prepares a continuation of her turn, as she then visibly inhales and opens her mouth twice (line 04). As Maria has self-selected one beat before, Ekaterina closes her mouth and glances up at Maria 0.6 seconds later (line 05). In the meantime, Maria has unlocked the display, opened the camera app, and moved her left hand to the phone. Ekaterina’s monitoring gaze can now perceive Maria’s adopted “photographer posture” (Figure 21), which makes her involvement in a new activity visible and the new activity recognizable. Ekaterina then responds to Maria’s assessment of the soup and starts looking at her face (line 06; Figure 22a/b). At this moment, Ekaterina orients to picture taking as Maria’s current main activity and suspends her storytelling.

Instead of agreeing with Maria’s assessment (Pomerantz, 1984), Ekaterina downgrades the artistic value of the food by offering to prepare the same soup at home for Maria (line 06). She thereby challenges the validity of Maria’s “reason for the picture,” which is also displayed by her steady gaze at Maria and tilted head (until line 09, Figure 23). Maria remains focused on choosing the frame for the picture (Figures 22a/b–23). This lack of response to Ekaterina shows that Ekaterina’s answer is not treated as an offer but is instead understood by Maria as a lack of agreement with her assessment. It might also indicate that Maria treats the picture taking as her individual activity instead of a possible joint topic or activity. One of the reasons why food photography can be unproblematically accomplished (i.e., designed and oriented toward) as a main activity is its projected short duration, which is visible in Maria’s embodied conduct: Maria is still holding the spoon in her left hand while taking the picture (Figures 20–24), indicating a quick return to the previously projected eating activity.

After 1.3 seconds, Maria finally snaps a picture of the soup (line 09, “PIC” in the multimodal annotation), then puts her phone back on the table while simultaneously locking the display (lines 09–10). Her subsequent sighing interjection (“lord,” line 10) connects back to Ekaterina’s suspended storytelling (lines 02 and 04) and provides a general, closing assessment. Both Maria and Ekaterina continue gazing down (line 12, Figure 25), and Ekaterina aligns to a closing of the previous part of the telling by providing a “formulaic expression” (line 12; Drew & Holt, 1998) before continuing on with a new aspect of the teacher’s complainable conduct (line 14).

Just as in Excerpt 1, in this excerpt picture taking is self-initiated and carried out individually by Maria, but this time it is designed and oriented to as her main activity. In this instance, the picture taking seems to be occasioned by the perception of the visual aspect of the food just before eating it. When initiating photo taking, Maria orients to the projected changes in the material environment or, more specifically, to the aesthetic properties of the soup. As a result, photo taking becomes a relevant action in an unsuitable sequential slot, in which Maria is expected to provide a response to her co-participant’s preceding action. The assessment of the food as photographable announces and accounts for Maria’s self-initiated smartphone use; it anticipates Ekaterina’s possible trouble in understanding the reason for this use and for the momentary unavailability of Maria as a recipient. By providing this assessment, Maria displays her new activity as being temporarily prioritized. Ekaterina’s challenging response to Maria’s assessment treats her interlocutor’s unavailability as possibly problematic and leads to the momentary suspension of her extended complaint (to which she finally links back after her alignment to Maria’s suggested closing of the sequence and activity, line 14).

If the arrangement of food for the picture requires specific actions on the part of other participants, food photography can also temporarily become a main activity for several participants. The following excerpt takes place about four and a half minutes before Excerpt 2; the three participants Dana (DAN), Tina (TIN) and Mikhail (MIK) are already discussing their joint university project. While speaking, Dana is pouring hot water from a thermos bottle into one of the three teapots on the table (line 01). As instead of flowing into the pot, the water seems to be restrained in the tea-strainer on top of the receptacle, Dana suspends both pouring the water and her turn (line 02). This attracts Tina’s attention and leads to a photographic project targeting the teapot. Tina has already taken a picture of her own teapot (to her left), which has been carried out as an individual side activity and without being accounted for or commented on by the other participants (similar to Ex. 2). For this reason, Tina is still holding her smartphone when the excerpt starts.

Excerpt 4. Teapot

Open in a separate windowWhile Dana is pouring water into the teapot located in the middle of the table, Tina is still turned slightly away from her co-participants and looking at her phone (Figure 26). Both Dana and Mikhail are already (and continuously throughout the excerpt) gazing at the teapot. When Dana notices that the water she is pouring is somehow withheld, she suspends her ongoing turn, retracts the thermos bottle, and displays her trouble by uttering several free-standing items (“interesting,” “alright,” and “okay,” line 02), and finally leans back and accepts it as not understandable (“mmm never mind,” line 03). Right after her initial assessment (“interesting”), Mikhail starts bending to the right, then down to inspect the teapot more closely (Mortensen & Wagner 2019). At the same time, Tina lowers her smartphone and starts glancing at the teapot as well (Figure 27). The fact that her gaze alternates between the teapot, Dana, and her smartphone (lines 02–03, Figures 27–29), however, indicates that she is not looking at the teapot in the same way as Mikhail does. Mikhail first describes what should normally happen next (line 4, “it will flow down there”) and therefore clearly links back to the observed mechanical problem. However, Tina requests her co-participants (and specifically Dana, at whom she is looking at the turn-beginning, Figure 30) to momentarily suspend any teapot-related actions so that she can take a picture (lines 05–07). The imperatives podozhdi (“wait”) and dajte (“let (me)”) display that she needs her co-participants’ alignment in order to take the picture. It also indicates that Tina treats multiple courses of actions as incompatible (Keisanen et al., 2014) and that she prioritizes photo taking over the ongoing activity – attempting to solve a problem with the teapot.

Quite early in her turn, Tina reaches for the teapot and starts moving it to a more central position on the table (lines 05–06, Figures 31–32). This arrangement and her description of it as “this technical miracle” (line 6) illustrate that the teapot is the central object she intends to take a picture of. She then recruits Dana for the picture by asking her (again) to pour water into the teapot (lines 6–7). Simultaneously with this directive turn, Tina picks up her smartphone with both hands and prepares to snap a picture. The other participants now suspend their ongoing inspection, and Tina’s prioritized activity becomes a joint activity. Without looking up to Tina, Dana immediately responds by bringing the thermos back in position above the teapot (line 07) and then pours some more water (lines 09–10). Tina takes two pictures: one before Dana starts pouring (line 09, Figure 33a/b) and another while she is pouring (line 10, Figure 34). Tina’s concurrent formulation of a caption for the pictures (“a teapot in which you need to pour hot water yourself,” line 10) accounts for her picture taking and illustrates the photographable feature of the object. This shows that food and drink photographables are not only chosen for their potential aesthetic quality but, more generally, for any remarkable feature they might possess for the observer. Conversely, Mikhail’s ongoing comments show that his interest in the teapot aligns with Dana’s initial observation, both verbally by evoking the expected outcome of the pouring (line 04), anticipating another problem (that the water might overflow, line 08), and formulating a closing assessment (“cool,” line 12), and bodily by bending towards the object from different directions (Figure 33a). Mikhail’s comment (line 08), however, is left unattended while picture taking is prioritized over other possible joint activities.

When Tina has lowered her smartphone and visibly finished her photographing activity (line 10, she locks the phone and puts it away), Dana links back to the practical problem she initially noticed, not aligning with Tina’s previously formulated point of interest (line 13, net, “no”). She then more explicitly relates to the problematic element of the teapot, that is, the strainer, at which she simultaneously points. Shortly afterwards, she abandons her technical investigation with a headshake and similar tokens to those she used in her initial noticing (“alright,” “never mind,” lines 16 and 18, see lines 2–3). Dana’s rather strong form of backlinking (De Stefani & Horlacher, 2008) to the noticing of the technical problem illustrates that she treats the picture taking as a suspension of her own ongoing inspection. The picture taking itself, however, is not treated as problematic by any of the participants. One reason for this is that, again, it has a projected rapid completion, after which the suspended activity can be resumed.

In Excerpt 4, picture taking is initiated and carried out as a temporarily prioritized activity for all the participants. Its mainness is collaboratively achieved, as Dana joins the activity by complying with Tina’s request, and the attempt to solve the technical problem recedes into the background. Taking a picture is designed not only as the main activity, but also as a joint activity (involving at least one co-participant, Dana) from the start, as her embodied action (pouring the water) is needed to accomplish Tina’s photographic project. The imperative podozhdi (“wait”) indicates that the invitation to participate in the picture taking is initially unilateral (Rossi, 2012). The necessity of suspending the ongoing inspection is then accounted for by the photographer, and the preferred form of her co-participants’ involvement is collaboratively negotiated.

5. Discussion and conclusion

In this article, we emphasized that taking photo of food and drinks with smartphones in mundane, face-to-face encounters can be accomplished (i.e., initiated and carried out) as either a main or a side activity. The way food photography is initiated depends on momentary opportunities and relevancies that emerge moment by moment. On the one hand, participants often initiate food photography when an opportunity to accomplish it without affecting the activity-in-progress emerges. Suitable “opportunity slots” for food photography can emerge when talk is suspended (Ex. 1) or when one of the participants finds themselves on the periphery of the embodied participation framework (Ex. 2). On the other hand, food photography can also be oriented to as a “now or never” activity, when an aesthetic or other remarkable feature of the object is bound to quickly disappear. If noticeable aspects of food are potentially “threatened” by the photographer (Ex. 3) or by co-participants (Ex. 4), food photography can be prioritized as a more relevant and “urgent” activity and, as result, emerge in an inadequate sequential slot. When initiating picture taking, participants, therefore, not only orient to sequential opportunities, but also to the temporal properties of the photographable object and projectable changes in the material environment. The way the activity further unfolds is then multimodally negotiated by all co-present participants, that is, the mainness or sideness of this activity is collaboratively achieved in situ (Mondada, 2014). In what follows, we will comment on some aspects which participants orient to when accomplishing the main or side character of this activity.

It is important to note that food photography is a ubiquitous and recognizable activity. A combination of the “photographer posture,” the orientation of the phone camera, and the photographer’s gaze makes this involvement accountable to co-participants. The approximate length (and a rapid completion) of this activity can, therefore, be projected by co-present others. Food photography is also an activity that typically requires neither the active contribution of others (as opposed to taking photos of other people, for example), nor the use of the photographer’s verbal resources. The photographer can provide a relevant response to their co-participant’s prior actions when taking a picture (Ex.1) or just after finishing this activity (Ex. 2). Consequently, co-participants often treat food photography as an individual side activity that does not require a suspension or abandonment of the activity-in-progress. Both verbal accounts for taking a picture and co-participants’ responsive turns explicitly referring to it do not always occur, which shows that the use of the smartphone as a camera is not an inherently problematic activity. Its accountability is assessed and negotiated by the participants mainly with respect to mutual orientation and availability (see also Robles et al., 2018; Oloff, 2021).

If photo taking is designed as a temporarily prioritized activity that suspends the activity-in-progress, it is not necessarily treated as problematic. Participants still orient to the projected length of the photo taking and promptly resume the previous activity after photo taking is accomplished (Ex. 3 & 4). In this case, however, participants are more likely to explicitly frame and comment on the picture taking (e.g., an assessment in Ex. 3). If specific actions are required from co-participants, these initial utterances usually literally formulate the upcoming action, (“let me take a picture” in Ex. 4), thereby acting as public announcements and making the imminent smartphone use publicly understandable (Suderland, 2020). The mainness of food photography can be collaboratively achieved by all participants, who suspend other ongoing activities and temporarily shift their attention to the object of photography or to the activity of photo-taking.

Analyzing activity suspensions and resumptions through the notions of mainness and sideness allows the researcher to underline the situated, multimodal, collaborative, and negotiated aspects of activity prioritization in social interaction. Recent research shows that smartphones are still frequently viewed as a disruptive technology that negatively affects interactions (e.g., research on “phubbing,” Aagaard, 2020, Rotondi et al., 2017). In this paper, we have demonstrated how a suspension of the main activity is negotiated in situ, and that a suspension is not always necessary for the accomplishment of a smartphone-based activity. While some activities can be easily designed and oriented to as side activities (e.g., food photography), others are potentially more “disruptive” (e.g., receiving a phone call) and lead more often to a change in the participation framework (Rae, 2001). However, instead of assuming the disruptive character of various technology-related activities, these activities could be better analyzed through the lens of their locally accomplished mainness and sideness.

Looking at the details of mundane food photography in social interactions can open up for multiple related interactional phenomena. Apart from the study of specific audible actions within this activity (such as response cries, announcements, assessments, and formulated captions), future research could focus on the diversity and implications of co-participants’ collaborative contributions to picture taking (e.g., by giving or complying with instructions or by simply suspending their own action for the picture to be taken); on the link between the ownership of the food and the entitlement for taking a picture of it; or on the formulation and negotiation of mundane aesthetics and creativity (e.g., identifying and curating photographables, and, later, their photographs). By providing a first illustration of the variety of food photographing practices in social interactions, our intention is to shift the conventional focus on food photographs as finished products to the ways these pictures actually come into being, and how smartphone-based food photography is organized in and as social interaction.

Funding

The data have been collected within the project “Smart Communication: The situated practices of mobile technology and lifelong digital literacies” (funded by the Eudaimonia Institute, University of Oulu (2018-2022), and the Academy of Finland (2019-2023)).

References

Aagaard, J. (2020). Digital akrasia: A qualitative study of phubbing. AI & SOCIETY, 35(1), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-019-00876-0

Aaltonen, T., Arminen, I., & Raudaskoski, S. (2014). Photo sharing as a joint activity between an aphasic speaker and others. Interacting with Objects: Language, Materiality, and Social Activity, 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.186.06aal

Asplund, S.-B., Olin-Scheller, C., & Tanner, M. (2018). Under the teacher’s radar: Literacy practices in task-related smartphone use in the connected classroom. L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 18, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.17239/L1ESLL-2018.18.01.03

Auer, P. (2018). Gaze, addressee selection and turn-taking in three-party interaction. In G. Brône & B. Oben (Eds.), Eye-tracking in Interaction: Studies on the role of eye gaze in dialogue (pp. 197–232). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/ais.10.09aue

Avgustis, I., & Oloff. F. (forthcoming). Collecting and analysing multi-source video data: Grasping the opacity of smartphone use in face-to-face encounters. In P. Haddington, T. Eilittä, A. Kamunen, L. Kohonen-Aho, T. Oittinen, I. Rautiainen & A. Vatanen (Eds.), Ethnomethodological Conversation Analysis in Motion: Emerging Methods and Technologies. Routledge.

Berry, M. (2015). Out in the open: Locating new vernacular practices with smartphone cameras. Studies in Australasian Cinema, 10(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/17503175.2015.1084173

Bolden, G. (2004). The quote and beyond: Defining boundaries of reported speech in conversational Russian. Journal of Pragmatics, 36(6), 1071–1118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2003.10.015

Brown, B., McGregor, M., & Laurier, E. (2013). iPhone in vivo: Video Analysis of Mobile Device Use. CHI '13: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1031–1040. https://doi.org/10.1145/2470654.2466132

Brown, B., McGregor, M., & McMillan, D. (2015). Searchable Objects: Search in Everyday Conversation. CSCW '15: Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 508–517. https://doi.org/10.1145/2675133.2675206

Chalfen, R. (1987). Snapshot versions of life. University of Wisconsin Press.

de Solier, I. (2018). Tasting the Digital: New Food Media. In K. LeBesco & P. Naccarato (Eds.), The Bloomsbury Handbook of Food and Popular Culture (pp. 54–65). Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474296250.0011

De Stefani, E., & Horlacher, A.-S. (2018). Mundane talk at work: Multiactivity in interactions between professionals and their clientele. Discourse Studies, 20(2), 221–245.https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445617734935

Deppermann, A., & Streeck, J. (Eds.). (2018). Time in Embodied Interaction. Synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resources. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.293

DiDomenico, S. M., & Boase, J. (2013). Bringing mobiles into the conversation: Applying a conversation analytic approach to the study of mobiles in co-present interaction. In D. Tannen & A. Trester (Eds.), Discourse 2.0: Language and new media (pp. 119–131). Georgetown University Press.

DiDomenico, S. M., Raclaw, J., & Robles, J. S. (2018). Attending to the Mobile Text Summons: Managing Multiple Communicative Activities Across Physically Copresent and Technologically Mediated Interpersonal Interactions. Communication Research, 47(5), 669-700. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650218803537

Drew, P., & Holt, E. (1998). Figures of speech: Figurative expressions and the management of topic transition in conversation.Language in Society, 27(4), 495–522. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4168872

Goffman, E. (1963). Behavior in Public Places: Notes on the Social Organization of Gatherings. Free Press.

Goodwin, C. (1981). Conversational Organization. Interaction between Speakers and Hearers. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500009647

Goodwin, C. (2007). Participation, stance and affect in the organization of activities. Discourse & Society, 18(1), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926507069457

Goodwin, M. H. (1997). Byplay: Negotiating Evaluation in Storytelling. In G. R. Guy, C. Feagin, D. Schiffrin, & J. Baugh (Eds.), Towards a Social Science of Language: Papers in Honor of William Labov 2: Social Interaction and Discourse Structures (pp. 77–102). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.128.08goo

Greer, T. (2016). Multiple Involvements in Interactional Repair: Using Smartphones in Peer Culture to Augment Lingua Franca English. In M. Theobald (Ed.), Friendship and Peer Culture in Multilingual Settings (pp. 197–229). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1537-466120160000021010

Haddington, P., Keisanen, T., Mondada, L., & Nevile, M. (Eds.). (2014). Multiactivity in Social Interaction: Beyond multitasking. John Benjamins.

Heath, C. (1982). The display of recipiency: An instance of a sequential relationship in speech and body movement. Semiotica, 42(2–4), 147–168. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1982.42.2-4.147

Heath, C. (1984). Talk and recipiency: Sequential organization in speech and body movement. In M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis (pp. 247–265). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511665868.017

Heath, C., Hindmarsh, J., & Luff, P. (2010).Video in Qualitative Research: Analysing Social Interaction in Everyday Life. SAGE.

Hellermann, J., Thorne, S. L., & Fodor, P. (2017). Mobile reading as social and embodied practice. Classroom Discourse, 8(2), 99–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2017.1328703

Hillman, T., & Weilenmann, A. (2015). Situated Social Media Use: A Methodological Approach to Locating Social Media Practices and Trajectories.Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 4057–4060. https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702531

Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In G. H. Lerner (Ed.), Conversation Analysis. Studies from the first generation. (pp. 13–34). John Benjamins.https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.125.02jef

Keisanen, T., Rauniomaa, M., & Haddington, P. (2014). Suspending action. From simultaneous to consecutive ordering of multiple courses of action. In P. Haddington, T. Keisanen, L. Mondada, & M. Nevile (Eds.), Multiactivity in Social Interaction: Beyond multitasking (pp. 109–134). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.187.04kei

Koskinen, I. (2006). Managing banality in mobile multimedia. In R. Pertierra & I. Koskinen (Eds.), The Social Construction and Usage of Communication Technologies: European and Asian Experiences (pp. 48–60). Singapore University Press.

Larsen, J. (2008). Practices and Flows of Digital Photography: An Ethnographic Framework. Mobilities, 3(1), 141–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450100701797398

Licoppe, C., & Figeac, J. (2018). Gaze Patterns and the Temporal Organization of Multiple Activities in Mobile Smartphone Uses. Human-Computer Interaction, 33(5-6), 311-334.

Licoppe, C., & Tuncer, S. (2014). Attending to a summons and putting other activities ‘on hold’: Multiactivity as a recognisable interactional accomplishment. In Multiactivity in Social Interaction: Beyond multitasking (pp. 167–190). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.187.06lic

Mandelbaum, J. (1991). Conversational non-cooperation: An exploration of disattended complaints. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 25(1–4), 97–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351819109389359

Mantere, E., & Raudaskoski, S. (2017). The sticky media device. In A. R. Lahikainen, T. Mälkiä, & K. Repo (Eds.), Media, Family Interaction and the Digitalization of Childhood (pp. 135-154). Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781785366673.00018

McMillan, D., McGregor, M., & Brown, B. (2015). From in the wild to in vivo: Video Analysis of Mobile Device Use. MobileHCI '15: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, 494–503. https://doi.org/10.1145/2785830.2785883

Mondada, L. (2007). Multimodal resources for turn-taking: Pointing and the emergence of possible next speakers. Discourse Studies, 9(2), 194–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445607075346

Mondada, L. (2009). The methodical organization of talking and eating: Assessments in dinner conversations. Food Quality and Preference, 20(8), 558-571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2009.03.006

Mondada, L. (2013). The conversation analytic approach to data collection. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), The Handbook of Conversation Analysis (pp. 32–56). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118325001.ch3

Mondada, L. (2014). The temporal orders of multiactivity. Operating and demonstrating in the surgical theatre. In P. Haddington, T. Keisanen, L. Mondada, & M. Nevile (Eds.), Multiactivity in Social Interaction: Beyond multitasking (pp. 33–76). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.187.02mon

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple Temporalities of Language and Body in Interaction: Challenges for Transcribing Multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878

Mondada, L. (2021). Sensing in Social Interaction: The taste for Cheese in Gourmet Shops. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108650090

Mondada, L. (2022). Conventions for multimodal transcription. Retrieved from https://www.lorenzamondada.net/multimodal-transcription

Mondada, L., Monteiro, D., & Tekin, B. S. (2020). The tactility and visibility of kissing: Intercorporeal configurations of kissing bodies in family photography sessions. In A. Cekaite & L. Mondada (Eds.), Touch in Social Interaction. Touch, Language, and Body (pp. 54–80). Routledge.

Mondada, L., & Tekin, B. S. (2020). Arranging bodies for photographs: Professional touch in the photography studio. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v3i1.120254

Mortensen, K., & Wagner, J. (2019). Inspection sequences – multisensorial inspections of unfamiliar objects. Gesprächsforschung - Online-Zeitschrift Zur Verbalen Interaktion, 20, 399–343. http://www.gespraechsforschung-online.de/fileadmin/dateien/heft2019/si-mortensen.pdf

Murtagh, G. M. (2002). Seeing the “rules”: Preliminary observations of action, interaction and mobile phone use. In B. Brown, N. Green, & R. Harper (Eds.), Wireless world: Social and interactional aspects of the mobile age (pp. 81-91), Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-0665-4_6

Ochs, E., & Shohet, M. (2006). The cultural structuring of mealtime socialization. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2006(111), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.154

Oksman, V. (2006). Mobile Visuality and Everyday Life in Finland: An Ethnographic Approach to Social Uses of Mobile Image. In J. R. Höflich & M. Hartmann (Eds.), Mobile communication in everyday life: Ethnographic views, observations, and reflections (pp. 103–119). Frank & Timme.

Oloff, F. (2019). Das Smartphone als soziales Objekt: Eine multimodale Analyse von initialen Zeigesequenzen in Alltagsgesprächen. In K. Marx & A. Schmidt (Eds.), Interaktion und Medien: Interaktionsanalytische Zugänge zu medienvermittelter Kommunikation (pp. 191–218). Universitätsverlag Winter.

Oloff, F. (2021). Some Systematic Aspects of Self-Initiated Mobile Device Use in Face-to-Face Encounters. Journal Für Medienlinguistik, 2(2), 195–235. https://doi.org/10.21248/jfml.2019.21

Paragas, F. (2005). Being Mobile with the Mobile: Cellular Telephony and Renegotiations of Public Transport as Public Sphere. In Mobile Communications: Re-negotiation of the Social Sphere (pp. 113–129). Springer.https://doi.org/10.1007/1-84628-248-9_8

Pomerantz, A. (1984). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. In Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511665868.008

Porcheron, M., Fischer, J. E., & Sharples, S. (2016). Using Mobile Phones in Pub Talk. CSCW '16: Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 1649–1661. https://doi.org/10.1145/2818048.2820014

Raclaw, J., Robles, J. S., & DiDomenico, S. M. (2016). Providing Epistemic Support for Assessments Through Mobile-Supported Sharing Activities. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 49(4), 362–379.https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2016.1199089

Rae, J. (2001). Organizing Participation in Interaction: Doing Participation Framework. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 34(2), 253–278. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327973RLSI34-2_4

Raudaskoski, S., Mantere, E., & Vakonen, S. (2017). The influence of parental smartphone use, eye contact and ‘bystander ignorance’ on child development. In A. R. Lahikainen, T. Mälkiä, & K. Repo (Eds.), Media, Family Interaction and the Digitalization of Childhood (pp. 173–184). Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781785366673.00021

Raymond, G., & Lerner, G. H. (2014). A body and its involvements. Adjusting action for dual involvements. In P. Haddington, T. Keisanen, L. Mondada, & M. Nevile (Eds.), Multiactivity in Social Interaction: Beyond multitasking (pp. 227–245). John Benjamins.

Relieu, M. (2008). Mobile phone “work”: Disengaging and engaging mobile phone activities with concurrent activities. In R. Ling & S. Campbel (Eds.), The Reconstruction of Space and Time: Mobile Communication Practices. Transaction Publishers.

Robles, J. S., DiDomenico, S., & Raclaw, J. (2018). Doing being an ordinary technology and social media user. Language & Communication, 60, 150–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2018.03.002

Rossi, G. (2012). Bilateral and Unilateral Requests: The Use of Imperatives and Mi X? Interrogatives in Italian. Discourse Processes, 49(5), 426–458.https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2012.684136

Rotondi, V., Stanca, L., & Tomasuolo, M. (2017). Connecting alone: Smartphone use, quality of social interactions and well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 63, 17–26.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2017.09.001

Rühlemann, C., Gee, M., & Ptak, A. (2019). Alternating gaze in multi-party storytelling. Journal of Pragmatics, 149, 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2019.06.001

Sahlström, F., Tanner, M., & Valasmo, V. (2019). Connected youth, connected classrooms. Smartphone use and student and teacher participation during plenary teaching. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 21, 311–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.03.008

Streeck, J., Goodwin, C., & LeBaron, C. (Eds.) (2011). Embodied Interaction. Language and Body in the Material World. Cambridge University Press.

Streeck, J. (2018). Times of rest: Temporalities of some communicative postures. In A. Deppermann & J. Streeck (Eds.), Time in Embodied Interaction: Synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resources (pp. 325–350). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.293.10str

Suderland, D. (2020). „oh isch FIND_s nich;“ Eine konversationsanalytische Untersuchung sprachlicher Bezugnahmen auf smartphone-gestützte Suchprozesse in Alltagsgesprächen. Journal for Media Linguistics, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.21248/jfml.2019.17

Tekin, B. (2017). The negotiation of poses in photo-making practices: Shifting asymmetries in distinct participation frameworks. In L. Mondada & S. Keel (Eds.), Participation et asymétries dans l'interaction institutionelle (pp. 285–313), L'Harmattan.

Wargo, J. M. (2015). Spatial Stories with Nomadic Narrators: Affect, Snapchat, and Feeling Embodiment in Youth Mobile Composing. Journal of Language & Literacy Education, 11(1), 47–64.

Weilenmann, A., & Hillman, T. (2019). Selfies in the wild: Studying selfie photography as a local practice. Mobile Media & Communication, 8(1), 42–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157918822131

Weilenmann, A., Hillman, T., & Jungselius, B. (2013). Instagram at the museum: Communicating the museum experience through social photo sharing. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI '13, 1843–1852. https://doi.org/10.1145/2470654.2466243

Wiggins, S. (2013). The social life of ‘eugh’: Disgust as assessment in family mealtimes. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(3), 489–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2012.02106.x

Zappavigna, M. (2014). CoffeeTweets: Bonding around the bean on Twitter. In P. Seargeant & C. Tagg (Eds.), The language of social media. Identity and community on the internet (pp. 139–160). Palgrave Macmillan.https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137029317_7