Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

The orderliness and sociability of “talking together”:

portrait of a conversational jam session

Chiara Bassetti1 & Kenneth Liberman2

1University of Trento, 2University of Oregon

Abstract

Conversations among Italians often entail many-at-a-time rather than one-at-a-time speaking. This “talking together” is a deliberate aim of parties and a relevant aspect of their social life. It is a variant system for organizing ordinary talk. We describe how simultaneity is organized, how participants collaborate to maintain the orderliness of their interaction, and how, to do so, they listen to each other and continuously monitor talk for its content and its form. Following Simmel, we see this as a classic example of sociability, a play-form of sociation.

Keywords: simultaneous talk, “talking together”, listening, sociability, ethnomethods

1. Introduction

On occasion Italians take pleasure in allowing their talking to drift into simultaneous utterances, a phenomenon to which we refer as “talking together.” A friendly Italian dinner table sounds like this:

Extract 1. “Simultaneous Talking”

Instead of being a deviation from proper behavior, such vociferous conversation (known in Italy as “chiacchierare”) holds a convivial nature and may be welcomed as an opportunity to have some fun together. The phenomenon has to be distinguished both from overlaps and temporary and/or conventional occurrences of simultaneous talk.

On the one hand, when the operative activity is simultaneous talking, rather than people speaking one-at-a-time, overlaps are more the background than the figure. More importantly, the notion of “overlap” refers to situations where speaking parties are competing for the floor (e.g., at turn-transition points, cf. Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson, 1974; French and Local, 1983; Schegloff, 2000). In the social phenomenon we are examining here, rather than simultaneous talking being largely driven by a competitive or strategic interest of individual speakers, as some contemporary EMCA analysts, including those researching epistemics, occasionally assume, the sociality of these conversations emphasizes a social context that is de-centered.

On the other hand, in talking together, simultaneity does not seem to be restricted to brief occurrences, such as greetings (e.g., Duranti, 1997; Pillet-Shore, 2012) or laughing (Sacks, 1972/1992, p. 571), nor to ritualized ones such as cheering, booing, chanting, praying and other collective performances during rites of several kinds — Fred Cummins (e.g., 2019) calls these ritualized instances “joint speech.” Moreover, the phenomenon is not restricted to close and intimate relationships, nor to mainly dyadic performances as “turn-sharing” is (Pfänder and Couper-Kuhlen, 2019).

In the Italian informal conversations we examine in this paper, simultaneous talk is the norm and the pleasure. This does not mean that in other social contexts, Italians do not engage in the one-speaker-at-a-time mode of conversing. Here our focus is a variant system of organizing ordinary talk; we are interested in describing what they are doing when they are talking together. Such a system, moreover, is not exclusive to informal conversations in Italian. We do not see simultaneous talk as intrinsic to the Italian language or to the people of Italy. Still, the phenomenon is ubiquitous in Italy, and the paper is based on Italian data.

There are various modes of talking at the same time. Here we analyze one of these modes, providing examples of the mechanics and systematics of these Italian speakers’ collaborative simultaneous speech. We highlight a number of collaborative routines or techniques — in a word, the ethnomethods (Garfinkel, 1967)—that interlocutors use for producing and organizing this talking together, for coordinating the conviviality of their conversations. The main question we explore is whether participants are able to hear each other while in the midst of such prolonged simultaneous talk. Some have argued that people who are talking simultaneously cannot pay proper attention to others’ talk (Ruhleder and Jorden, 2001). Our study discovered that instead, the kind of conversational organization under examination requires parties to monitor closely each participant’s contributions. It is a highly organized, although emergent, collaborative practice.

Our interest in local methods for concerting activities makes our study ethnomethodological. Our work, moreover, relies upon insights gained from conversation analysis (CA), and makes use of some CA devices (e.g., for transcripts). However, it does not rely on collections. Rather, we analyzed the audio- and video-recorded conversations of our corpus (see Table 1) in full and in their own right — a series of single case analyses (cf. also Watson, 2008) — and we identified several methods that participants use, in various combinations at any one point, for coordinating their simultaneous speech and for celebrating their sociability. Simmel and Garfinkel grounded our inquiries. From a CA perspective, Sack’s and Jefferson’s work is also important for our analysis. Much of our data consists of simultaneous talk, a situation that led us to color-code our transcripts and to use several symbols for annotating the simultaneity of the talk1. Finally, it should be mentioned that participant observation was also employed beyond our recorded occasions.

Table 1. “Participants in recorded conversations”

| Nr. of participants | Gender | Age | Occasion | Recording |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1 W, 5 M | All: 35-45 | Dinner at a friend’s place (indoor) | Audio |

| 6 | 6M | All: 35-45 | Evening at a friend’s place (indoor) | Audio |

| 7 | 1W, 6M | All: 35-45 | Dinner at a friend’s place (indoor) | Audio |

| 5 | 1W, 4M | All: 35-45 | Dinner at a friend’s place (indoor) | Audio |

| 6 | 6M | All: 35-45 | Evening at a friend’s place (indoor) | Audio |

| 12 | 4W, 8M |

4: 35-45 8: 65-75 |

Family and friends’ festive lunch (outdoor) | Audio |

| 8 | 3W, 5M |

3: 35-45 5: 65-75 |

Family and friend’s dinner (indoor) | Audio |

| 10 | 5W, 5M | All: 35-45 | Wedding dinner table (outdoor) | Video |

| 6 | 3W, 3M |

4: 35-45 2: 55-65 |

Family dinner: birthday celebration at home (indoor) | Audio |

| 6 | 1W, 5M | All: 35-45 | Dinner at a friend’s place (indoor) | Video |

| 6 | 3W, 3M |

3: 15-25 1: 35-45 1: 55-65 1: 65-75 |

Family and friends’ dinner at home (indoor) | Audio |

2. Cocreating rhythm

Repetition is a device that is used frequently during simultaneous talking. We have observed that many conversations include lexical repetition, both of self and others. Participants not only repeat words, they repeat prosodic contours and also align the pacing of their syllables (see also Reed, 2007). Repetition and echoes can produce conviviality and can be used effectively to set into motion a rhythm for speaking. When parties repeat each other’s phrases, they may be warming up for more cadenced talking together2. That is, repetition can act as an initial driver of simultaneous talk.

Extract 2 displays lively simultaneous speaking. The vociferous talking is initiated by means of a repetition of lexical items at lines 1, 4, 5 and 8, and 6), which carry the collective speech to an apex (0:06-07). The parties concert their talking vigorously:

Extract 2. “The Energy of Repetitions”

At line 1, L’s lexical repetition of his own words (ormai and si è imbruttito) gives the confab a vigorous start and sets up a cadence for the speaking that can be heard imitated by A (at lines 2-3), even though A employs no lexical repetition. Both cadence and lexical repetition are carried forward by C (line 4, 0:04), and her words are repeated by another speaker (S), along with a cheer (brava) at line 6 (0:05). Meanwhile, at lines 5 and 8 (0:06-07), another participant (L) employs elongations in the way other parties did before and continues with lexical repetitions (Sì and Capra). This is the sound of lively sociation.

There are two varieties of repetition: repetition of others and repetition of oneself, and both are able to contribute to the pacing of a course of conversation. Repetition of oneself, especially of a vigorous sound pattern, has efficacy in energizing a colloquy by establishing and making public a rhythm that can be followed. Repeating another’s phrasing can additionally be used to indicate agreement or friendliness, and above all, it marks mutual listening.

In Extract 3, the repeated words give material substance to the collaborative energy. It happens twice. In the first instance, a female3 speaker’s (R’s) repeated coso di bagaglio (“thing of stuff,” a meaningless expression in Italian as much as in English) is echoed by two other participants, first a man (M, line 3) and then a woman (C). A third conversationalist (F) provides a creative repetition, inverting the two terms (bagaglio del coso, line 9) — what Liberman (2004, pp. 123-32) called “reversals” in his Tibetan debating study. In the second instance, another male speaker (N) picks up only a single word, cos4 , and produces a dopo il cos (“after the thing”) at line 12, 0:09 (recalling a piece of talk taken from an earlier moment in the same conversation), and this is repeated by C at line 14. Encouraged by the repetition of his phrase, the speaker rehearses it at line 15, and the woman repeats it one more time (second instance in line 14, after the pause):

Extract 3. “Duets”

The pattern of speakers here, N-C-N, gets the conversation moving briskly. The speakers perform a duet with dopo il cos (“after the thing,” lines 12-15). A second male speaker offers a public summary (È così, “It’s like that,” lines 16 and 18), which provokes an echo from N. Encouraged by this, M turns the phrase è così into a second duet, M-N. The way that these speakers concert their utterances displays harmony; or rather, the display is the harmony.

In both varieties of repetition, picking up words that are especially sonorous and repeating them is a preferred way to infect the talk with energy. Both Sacks and Jefferson were attentive to the effects of “sound patterns,” including repeated sounds and “sound selection” (Jefferson, 1996, pp. 2 and 6), which involves the tendency of sounds already spoken to locate similar sounds. Selection of lexical items for sound rather than meaning can serve to animate a group of simultaneous speakers. In the following extract, the use of tremende (“terrible ones”) exploits the physical assets of the word for the purpose of animating the parties.

Extract 4. “Physicality of Lexical Selection”

Tremende is first expressed by an elderly woman (G, line 8, 0:07) in a somewhat cautious way, but a younger woman (C) picks up the item and gives it the full rhetorical force it is able to bear, taking advantage of how the intensity of its physical substance can be made to embody its sense. She repeats it twice at line 10 (0:08-09). Also, in line 5 G picks up C’s earlier ma::mme (from line 1) and employs its prosodic contour (repeated in C’s asi::lo) through her enunciation (do::nne). In turn, C retains that sound pattern, but also swiftly changes her terri::bili (line 7) to conform with G’s more powerful treme::nde. The prosody generated by the repeated tremende is carried forward in the enunciation of duplicemente and ovviamente (line 13). This acts as a metronome that serves to energize the speakers. As Garfinkel (2002: 150-53) observes about a metronomically propelled musical performance, the locally produced, developing phenomenal details of some metronomic talking launches the cohort of talkers together and provides them an organization to follow. As Garfinkel (2002: 252) writes, “We are in the midst of an organizational thing: we cannot take all the time in the world to play the prelude.” Throughout this long and somewhat dense clip, pitch is employed to keep the conversation propelled. The force generated that way enlivens this sequence of talking together, which features two parallel but intertwined conversational tracks that share a general topic (SUVs) as well as the underlying sound pattern. Notice that C and M, who are apparently engaged in different tracks, still manage to match each other in pitch, tempo and some lexical selection (perché, at lines 23-24). Egbert (1997, p. 31) has noted a similar copying of modal particles across two tracks of simultaneous talking. M restarts speaking and picks up C’s just-enunciated perché; in lines 25 through 28, M and C mirror each other's prosodic contours, using the vowel “a“ of Duca:to!, camion, d’a:rme, and Santi and the labial “m“ of d’a:rme, nu::mi!, and camion to produce a harmony inside which their congenial relations are made to thrive.

Sharing a rhythm or style of speaking over a course of talking together is a way to accomplish harmony and conviviality. Pfänder and Couper-Kuhlen, (2019, p. 27) detail several interactional tools that speakers use for concerting “highly rhythmic choral production.” In our analysis we identified lexical repetition, volume alignment, replicating the pitch and styles of vowel-elongations, and the prosodic contours of phrases more generally. In Extract 5, the group’s enthusiasm is given impetus by the Ahh! at line 4 (0:06), as well as by a growl (the “ua::r” of gua::rdo, line 6). This inaugurates a swarm of speech, something like what Jefferson (1996, p. 30) has called a “sound flurry.”

Extract 5. “Wall of Sound”

A common token of assent heard in many Italian conversations, “Ah” often works as a means for coordinating for incipient simultaneous talk, a means to collectively set up a rhythm — for tuning up, so to speak. In the case above, the prosodic contour of M’s elongated Ah is picked up by L’s gua::rdo (line 6). The simultaneous speech is then set to the rhythm of the female speaker’s staccato (lines 9, 11 and 14, 0:09-16), which recycles previous conversational material with her gua::rdato (line 9) and gua::rdo (line 14). Vocal gestures that are elongated or that replicate a prosodic contour enhance the energy of the collaborative speaking. The speakers monitor the talking for its volume and adjust to it. The tonality of the speaking also plays a role.5 These tools are used to vivify the conversation and require close and constant attention to co-participants’ contribution.

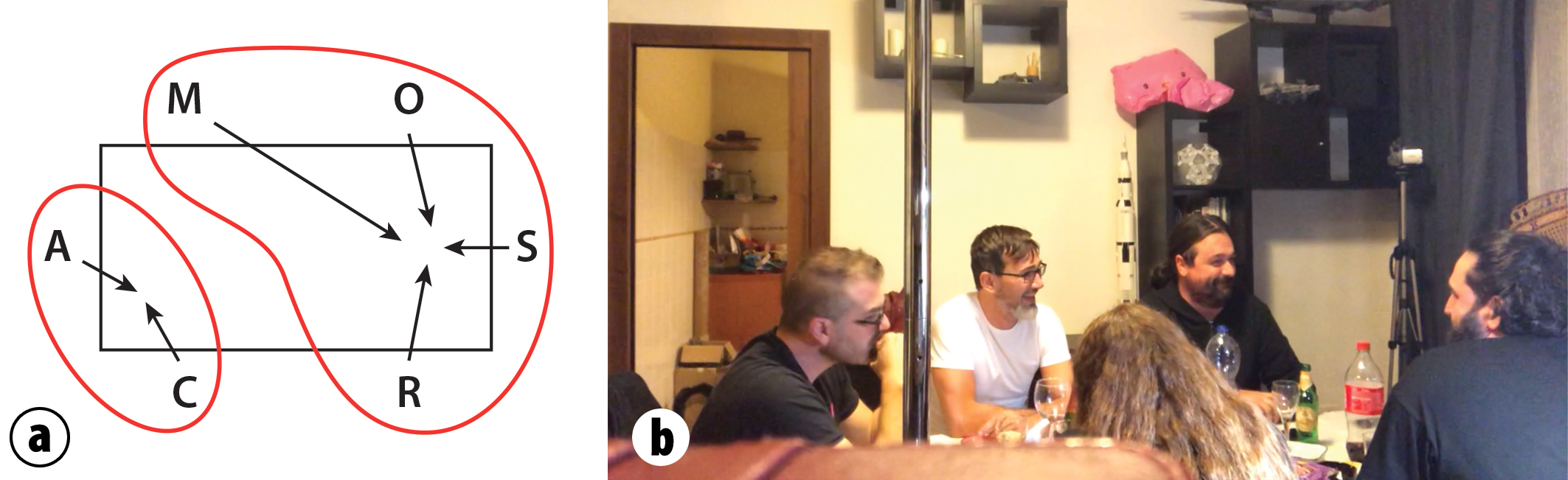

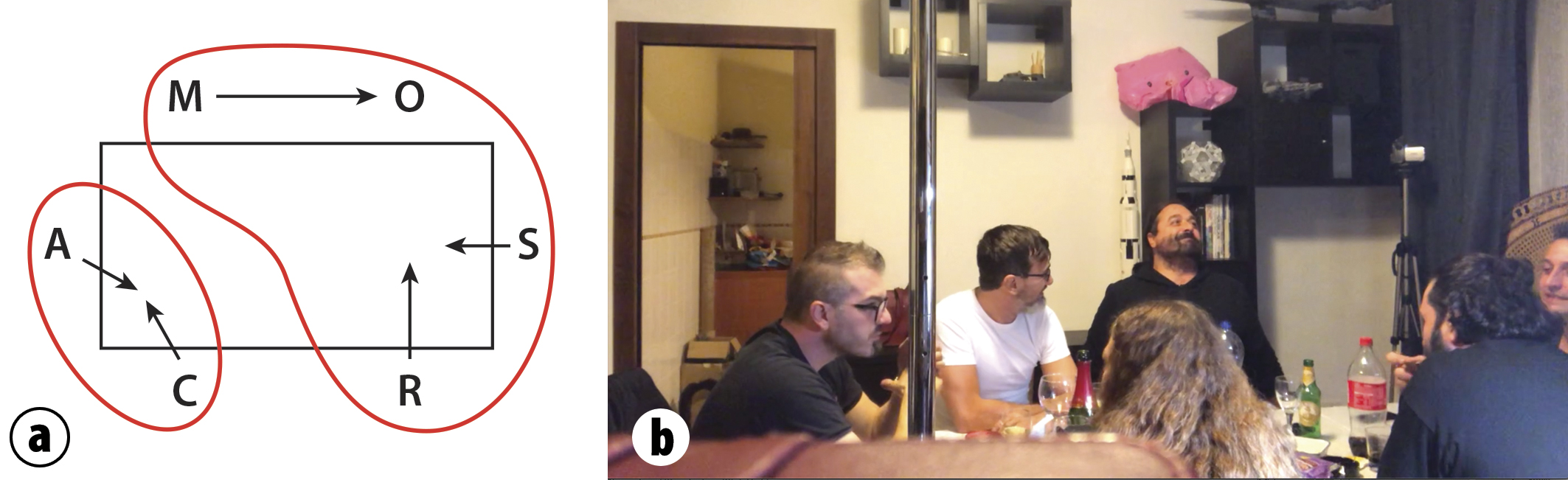

Speakers not only monitor the talk for its sense, but also for its rhythm and its aesthetic form. These conversationalists cultivate flourishes of sound, and this allows the number of people who participate simultaneously to increase. To show how rhythm can work even beyond lexical items, contents, and ultimately concepts, we propose another example, involving repeated grunting by three participants. The first grunting is produced by R at 0:05-06 of Extract 6 (Figure 1); it is repeated by R himself and joined by O at 0:08. This successfully animates the speakers, so successfully that R repeats his performance twice more: at 0:14 (Figure 2) and at 0:20-21. This prompts O into a virtuoso performance of his own at 0:22-23 (Figure 3, where O attracts the attention of M and R), joined also by S at 0:24 (S is partly visible in the clip, see 0:27):

Extract 6. “Grunting Trio”

The laughter at 0:02 by R, who sits lower right, starts the conviviality rolling and causes the speakers to grin. M is attentive to both conversations: the laughter attracts his attention for a moment, yet from 0:05-08 he listens to the conversational track involving C and A (call it track 1, see Figure 1). Following the short duet of grunting at 0:08, M shifts his attention back to track 2 (0:09). The parties demonstrate that they are able to follow more than one conversational track at the same time. What is most interesting from this point of view is that despite O being one of the principal participants in the grunting conversation, when the partner of C in conversational track 1 finally speaks (at 0:30), he captures O’s attention (Figure 4), which is proof that the parties are monitoring both tracks at the table. Some viewers may describe talk like this as “cacophony,” but when the simultaneous talk produces good cheer and it is both organized and pleasant, “harmony” seems a more appropriate descriptor.

3. Several tracks, one conversation

That these participants who are talking together hear each other is evident from their selection of words and sounds, their maintaining topics at hand, their responding to questions appropriately, and the success of their collaboration. We can conclude from our data that following a turn-taking regime whereby one person possesses a turn of speaking at a time is not anything that is essential for the attention that conversing parties pay to each other. But there is more: they are capable of hearing each other well even when the group’s conversation has split into two concurrent discussions, or more than one conversational track.

We found an interesting case in our corpus, which we only summarize given its length. It commenced with a double-track conversation featuring C and L speaking together about topic #1, while at the same time M, A and S were discussing topic #2. This continued for more than 13 minutes. Once topic #1 was exhausted, C turned to the whole party, brought everyone’s attention to the liqueur that was sitting on the table, and triggered a humorous excursus. All participated in this single-tracked excursus (topic #3), lasting about two and half minutes. The conversation then divided again into two parallel tracks, with different subgroups of participants and two additional topics. Following this, all rejoined in a single track (a topic #6). Then, the conversation became double-tracked once again: one involving A and C, the other L, M and S. Even though A was engaged in the lengthy conversational track with M and S at the outset, he produced implicit evidence — through a well-positioned quick comment in collaborative overlap with C’s talk6 — of having been listening to what C and L were saying 5 to 15 minutes earlier on topic #1 (back before the conversation became single-tracked for the first time). In a situation such as this, we observe that the talking together was not simply a consequence of there being multiple but separate conversations. Rather, participants juggle with(in) multiple conversational tracks and — in, as and for doing so — they are clearly oriented to one single activity, that is, talking together. The simultaneity here is not of activities or courses of action (e.g., Mondada, 2011; Haddington et al., 2014), but of participants’ contribution to the conversing.

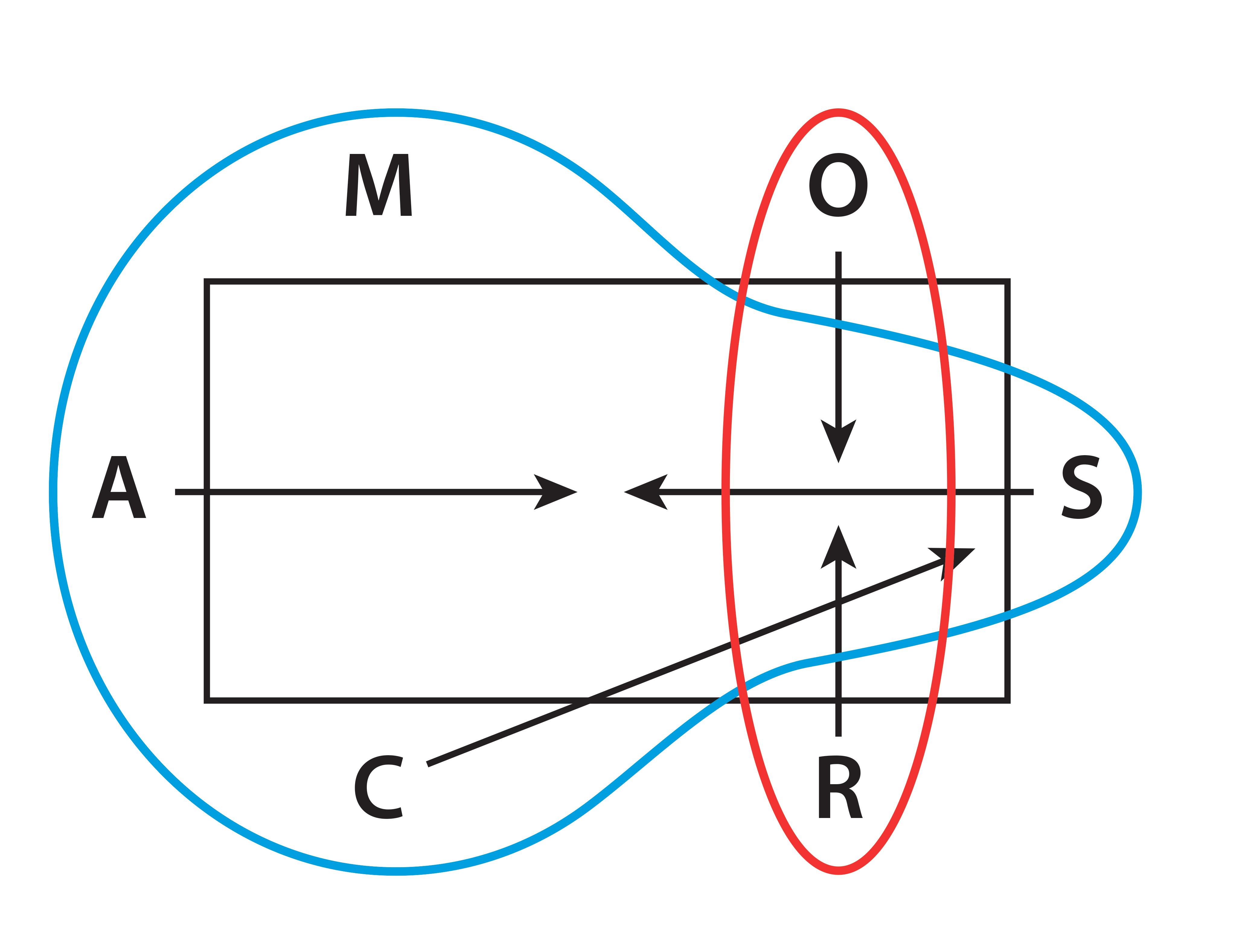

As a final example, consider Extract 7.7 It involves two concurrent discussions, crisscrossed around the table (Figure 5); we call it red track and blue track. The clip commences when A repeats his question to S with an emphatic tone, gesture and facial expression. This elicits monitoring gazes from O and R, although engaged in a different track (line 2). Later, the voice of C, who is questioning A, attracts the attention of R, who disengages O to pay attention to the blue track (line 7, looking at A), to which he later verbally contributes (line 9). Similarly, O quickly looks at C speaking, but then tries to catch S’s attention (line 7), possibly to start another track; unsuccessfully, as S remains engaged in the blue track, O turns his attention there as well (fig. 5.5).

Extract 7. “Juggling Conversational Tracks”

Open in a separate window

Clearly, on this occasion the parties are attending to both tracks. The phenomenon has to be distinguished from “schisming” (Egbert, 1997), as parties do not divide into proper (sub-)conversations; rather, they contribute to a conversation that has more than one track. This resonates more with what Sutinen (2014) calls “navigating multiple involvements multimodally,” but the interaction we consider here is not best identified by multiactivity (e.g., role-playing and setting a date for a future meeting); the activity — if we have to distinguish it from a conversational topic, or recipient — is a single one: talking together. At times there may be separate conversational tracks, but the parties are capable of coursing among them freely and contribute to more than one track at a time. They can do this only because they have been attentive to all tracks, regarding both their content and their form.

It seems, therefore, that the one-person-speaking-at-a-time species of concerting conversations is not any pure land for paying attention to others. Actually, it may be that when conversing under the guidelines of a more rigorous protocol of individualized turn taking, people need to divert some attention to their own thoughts and compose their intended phrasing while waiting (and sometimes competing) for an opportunity to take the turn. This is not the best way one improvises with others.

4. The form of sociability

In a large number of informal situations among Italians, simultaneous multi-party vocal participation emerges as a welcomed, concerted production, and the preferred local method for conversing. Participants in talking together do not seek control or power but only “pure sociality” (Schutz, 1971a, p. 199). That is, their main concern and aim is sociability, which Simmel (1949) defined as the play-form of sociation. According to Simmel, sociability is not goal-oriented, and does not entail any utilitarian, strategic or self-centered attitude. Rather, it entails collaboration. As Hammersley (2018, p. 48) underlines, Simmel put at the center of sociability “its playful and/or entertaining character, where external differences in status and position (and also, he suggests, personality and individuality) are downplayed.” Goffman (1961) resumed and enhanced this Simmelian argument in his analysis of the "rules of irrelevance" of social encounters, parties in particular. Categorizing practices (e.g., Watson, 2015) are certainly at play in the wordly usage of such rules.8

Furthermore, in discussing "purely sociable conversation,” Simmel (1949, pp. 259-260) stresses the role of form over content:

In order that this play may retain its self-sufficiency at the level of pure form, the content must receive no weight on its own account... Not that the content of sociable conversation is a matter of indifference; it must be interesting, gripping, even significant — only it is not the purpose of the conversation… since the matter is only the means, it has an entirely interchangeable and accidental character… All sociability is but a symbol of life, as it shows itself in the flow of a lightly amusing play; but, even so, a symbol of life.

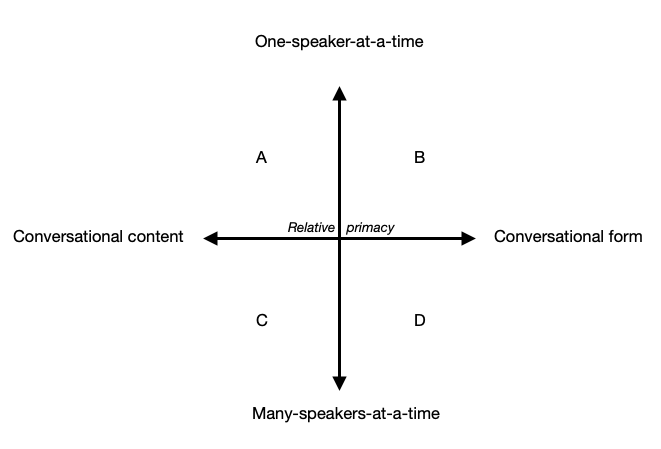

Conversations can thus be characterized by the relative primacy of the content — what is to be expressed (the topic at hand and connected opinions, “the matter”) — or of the form (the way it is expressed, the meter, the prosody, and lexical selection). While some tension between the two can exist, our interest in the “relative primacy” of one of these two implies there is duality without dualism (Breiger, 1974, as cited in Lizardo, 2019, p. 95).

Conversations can also be categorized according to the extent to which they are organized by a single-speaker-at-a-time format or feature multi-speakers who talk simultaneously. The former can offer opportunities for simultaneous talk, as discussed by Egbert (1997) and by Lerner (2002); and people who participate in “talking together” can engage in individualized turn-taking. Still, in any situation, one or the other conversational organization will have relative primacy. Based on our data, it seems that conversation-as-play is easier to carry out when the content of the conversation does not vie for primacy alone, as Simmel already noticed, and when there is no strict regime of one-at-a-time turn-allocation rules.

Interestingly, the single occurrence in our corpus when a speaker attempts to temporarily halt, or "suspend" (Keisanen, Rauniomaa and Haddington, 2014), simultaneous talking is done for the purpose of enhancing the party’s focus upon the content, relative to the conversational form. It required considerable interactional work and was only partly successful. The speaker was not trying to claim a single-speaker-turn for himself but only to preserve the common understanding of the topic at hand, which had been placed in jeopardy. In our data, the importance of the form generally exceeds that of the content, and it could be the case that any upgrading of the importance of the content will require reducing the amount of simultaneous talking. Relative primacy is a dynamic matter.

In Figure 6, the relative primacy of content and form is represented along the horizontal axis, and the single-speaker-at-a-time vis-à-vis many-speakers-at-a-time organization is arrayed along the vertical axis. Looking at this typology, we may notice that these four varieties have been studied unevenly. Most of CA literature addresses quadrants A and B. That is, CA has overwhelmingly analyzed conversations where the alternation of turns at talk is key. The lacunae in conversational studies exist in quadrants C and D, and the interactional methods that reside there merit further exploration. Here we mostly investigated Quadrant D. It remains to be determined whether Quadrant C is populated, a question further raised by the above recounted attempt to halt simultaneous talking. As the latter shows, however, the typology can serve to trace the processual development of any conversation via its positioning in terms of combined relative primacies. The figure is nothing more than a representational tool, a knowledge artifact (e.g., Lynch and Woolgar, 1988); however, relative primacy is a locally concerted, evolving phenomenal property. The scheme, therefore, can support the analysis of interaction as an ongoing developing phenomenon also with respect to conversational features — the relative primacy of content/form and of one/many-at-a-time organization — that are not usually considered, especially as changing properties.

5. Conclusion

Communicative resources and conversational ethnomethods vary across communities and cultures. The practices of gesture documented by Adam Kendon (2004) in Naples and Britain are a case in point. Our principal aim has been to provide an initial ethnomethodological portrait of just how Italians accomplish their collaborative simultaneous speaking, i.e. “talking together,” thereby sharing social conviviality, and how the close monitoring of others’ talk is a key to such a collective, improvised performance.

Simultaneous speech can be the aim, the activity, and the pleasure. It is a social form that is more than a brief, ritualized accomplishment, and it is something to be sustained. Above all, it is a group activity rather than a dyadic one. It is a mundane social form that is not exclusive to intimate or close relationships. If there is a requirement for participation, it would be knowing how to practically join in the talking together, which is every bit as sophisticated a system for organizing social interaction as the turn-taking systematics described by Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson (1974). These two forms of collaborative organization of speaking are both highly organized, and each has its own orderliness. The sociality produced by talking together is a locally choreographed achievement. As such, participants’ listening is not at all hampered; rather, it is enhanced. Interlocutors monitor the form, alongside the content, of co-participants’ enunciations — much like in a jazz jam session — and the event leads the parties. As in any jam session, moreover, “pure sociality” and fun are not only crucial ingredients — as vital as the knowledge of the relevant ethnomethods is — but also the reason for the activity.

Hopefully, our portrait of Italian talking together may bring other researchers to investigate these sorts of conversational jam sessions. There is plenty of terrain to cover. How gesture, mimicking and proxemics feature in prolonged simultaneous talk requires further investigation — the analysis we provided here simply hints to the multimodal character of talking together. Much work remains to be done identifying various ethnomethods and understanding the roles of these practices in human conversation and everyday interaction. Further analysis, development of more precise methodological tools, and an integrated theory lie on the horizon of such ethnomethodological studies of conversation.

References

Cummins, F. (2019). The Ground from Which We Speak: Joint Speech and the Collective Subject. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Duranti, A. (1997). Polyphonic discourse: Overlapping in Samoan ceremonial greetings. Text, 17, 349–381.

Egbert, M. (1997). Schisming: The Collaborative Transformation From Single Conversation to Multiple Conversations. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 30(1), 1-51.

French, P., & Local, J. (1983). Turn-competitive incomings. Journal of Pragmatics, 7(1), 17-38.

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in Ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Garfinkel, H. (2002). Ethnomethodology’s Program. Working Out Durkheim’s Aphorism. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Hammersley, M. (2018). The Radicalism of Ethnomethodology. Manchester, U.K.: University of Manchester Press.

Haddington, P., Keisanen, T., Mondada, L., & Nevile, M. (2014, Eds.). Multiactivity in Social Interaction: Beyond multitasking. Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Jefferson, G. (1984). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In G. H. Lerner (Ed.), Conversation analysis studies from the first generation (pp. 13–31). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Jefferson, G. (1996). On the Poetics of Ordinary Talk. Text and Performance Quarterly, 16(1), 1-61.

Keisanen, T., Rauniomaa, M., & Haddington, P. (2014) Suspending action: From simultaneous to consecutive ordering of multiple courses of action. In P. Haddington, T. Keisanen, L,, Mondada, & M. Nevile, (Eds.). Multiactivity in Social Interaction (pp. 109-133). Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Kendon, A. (2004). Contrasts in Gesticulation: A Neopolitan and a British speaker compared. In C. Müller & R. Posner (Eds.), The Semantics and Pragmatics of Everyday Gestures (pp. 173-93). Berlin: Weidler Buchverla.

Lerner, G. (2002). Turn-sharing: the choral co-production of talk in interaction. In C. Ford, B. Fox & S. Thompson (Eds.), The Language of Turn and Sequence (pp. 225-256). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Liberman, K. (2004). Dialectical Practice in Tibetan Philosophical Culture: An Ethnomethodological Inquiry Into Formal Reasoning. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Lizardo, O. (2019). Simmel’s Dialectic of Form and Content in Recent Work in Cultural Sociology. The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory, 94(2), 93-100.

Lynch, M., & Woolgar, S. (1988). Introduction: Sociological orientations to representational practice in science. Human Studies, 11, 99-116.

Mondada, L. (2011). The organization of concurrent courses of action in surgical demonstrations. In J. Streek, C. Goodwin, & C. LeBaron (Eds.), Embodied interaction: Language and body in the material world (pp. 207–227). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: transcribing multimodality. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 51(1), 85-106.

Pfänder, S., & Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2019). Turn-sharing revisited: An exploration of simultaneous speech in interactions between couples. Journal of Pragmatics, 147, 22-48.

Pillet-Shore, D. (2012). Greeting: Displaying Stance Through Prosodic Recipient Design. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 45(4), 375-398.

Reed, B.S. (2007). Prosodic Orientation in English Conversation. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ruhleder, K,, & Jordan, B. (2001). Co-constructing Non-Mutual Realities. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 10(1), 113-138.

Sacks, H. (1972/1992). Lectures in Conversation. Edited by Gail Jefferson. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn Taking in Conversation. Language, 50(4), 696-735.

Schegloff, E. (2000). Overlapping talk and the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language in Society, 29, 1–63.

Schutz, A. (1971a). Mozart and the Philosophers. In Collected Papers, Vol. II (pp. 179-200). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Simmel, G., & Hughes, E. (1949). The Sociology of Sociability. American Journal of Sociology, 55(3), 254-261.

Sutinen, (2014). Negotiating favourable conditions for resuming suspended activities. In P. Haddington, T. Keisanen, L,, Mondada, & M. Nevile, (Eds.). Multiactivity in Social Interaction (pp. 137-165). Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Watson, R. (2008). Comparative Sociology, Laic and Analytic: Some Critical Remarks on Comparison in Conversation Analysis. Cahiers de praxématique, 50, 203-244.

Watson, R. (2015). De-Reifying Categories. In R. Fitzgerald & W. Housley (Eds.), Advances in Membership Categorisation Analysis. London: Sage.

1 As well as using a different color for each speaker in any excerpt, we make use of two to three symbols — depending upon the complexity and number of participants — to mark the beginning of simultaneous talk: double slash (//), double squared brackets ([[) and, when necessary, double curly brackets ({{). We use an equal sign (=) to indicate continuity of talk by the same speaker whenever we were required to start a new line, whereas an asterisk (*) marks continuity between the talk of different speakers (i.e., between the end of the talk of one speaker and the beginning of another's talk). The other notation symbols are those elaborated by Jefferson (1984). Given the complexity, we present the transcripts in the original Italian, first, and then in English; in case of (minor) discrepancy among the two in terms of line numbering, we make reference to the Italian version.

2 For a detailed ethnomethodological treatment of how Tibetans use repetition to organize the dialectics in their public philosophical debates, and to energize those debates, see Liberman 2004: 123-32.

3 We provide this kind of information to facilitate the fruition of the audio/video clips — as a social member, the reader’s ear is trained also in gender terms.

4 “Cos” is the elided form of “coso,” which is in turn the vulgar form of “cosa,” “thing.”

5 Accompanying smiles, nods, and hand gestures (not available on the audio tape) also can serve to activate each participant’s spirit.

6

C: E’ lo stesso discorso che f//acevo prima con

A: //Sì certo certo

C: It’s the same discourse I //was doing earlier with

A: //Yeah sure sure

7 In this transcript, we employ Mondada’s (2018) conventions for multimodal transcription and accordingly, we mark overlaps in talk with a single squared bracket ([) only and we put English translation right below the original Italian. We still use different colors for different speakers.

8 “Pure sociality” is not devoid of serious social matters such as status, but from participants’ explicit, visible orientation to such matters. These categories are not external, but kept external, and other categories may be at play. The methods used to achieve that, however, are not the object of this paper, but will be taken up in a separate article.