Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Touch in achieving a pedagogically relevant focus in classrooms

Sara Routarinne1, Pilvi Heinonen2, Ulla Karvonen2, Liisa Tainio2 & Maria Ahlholm2

-

1University of Turku

-

2University of Helsinki

Abstract

This article focuses on touch, talk and embodied resources as a means of directing participants’ attention to a focal point in a pedagogical task. The data are drawn from a corpus of approximately 150 hours of video-recorded lessons from primary and lower secondary classrooms in monolingual and multilingual settings in Finland. The data were scanned for episodes of touch that occurred between teachers and students in relation to an ongoing pedagogical agenda. Using multimodal conversation analysis, we identified a complex multimodal gestalt (CMG; Mondada 2014a) consisting of touch followed by a deictic pointing gesture that occurred within an ongoing pedagogical activity. We present three excerpts from different pedagogical contexts that involve such a CMG as a means of directing a recipient’s attention to a pedagogical task. The CMG is relevant for managing attention within an ongoing learning task. We show how this CMG provides parallel participation frameworks without competition for the speaker, and argue that it is a technique for bringing together the teacher, student and content in ways that encourage the recipient’s attention to the pedagogical content. This analysis contributes to the growing body of studies on haptic sociality, especially in the institutional context of education.

Keywords:

touch, joint attention, pedagogical interaction, complex multimodal gestalt, classroom, multimodal conversation analysis

1. Introduction

An essential communicative action during pedagogical activities is to direct another’s attention to an object of focus. In this article, we explore how talk and embodied resources, especially touch, work together to direct a recipient’s attention to a focal point in classroom learning environments. We focus on cases in which one participant ostensibly notices that another participant is not attending to the relevant content and treats this lack of attention as demonstrably missing. We detail ways in which teachers use touch to direct individual students’ attention to a focal point within learning tasks, and students use touch to draw a teacher’s attention to the content to be worked on. Thus, the phenomenon under investigation is the pursuit of attention that involves one participant touching another during pedagogical activities.

Our study contributes to the growing body of research within ethnomethodological conversation analysis on haptic sociality (Cekaite 2015, 2016; Goodwin 2017; Goodwin & Cekaite 2018; Streeck 2013). Thus far, studies that have an educational focus have primarily been conducted in early childhood settings. Research reports that haptic means are used predominately for the socio-relational work of controlling, comforting and assisting, and, to some extent, for teaching academic content (Bergnehr & Cekaite 2018). Touch is also used in socializing preschool children to culturally appropriate behavior (Burdelski 2010; Burdelski 2020; Burdelski & Mitsuhashi 2010), and to soothe children when they are in distress (Burdelski this issue; Cekaite & Kvist Holm 2017). In the secondary school context, touch is reported to be a resource for off-task peer socialization during the playful teasing that teenagers engage in (Tainio 2016). Furthermore, it is used as an attention-getting device between peers that enables them to construct participation frameworks that are parallel to the ongoing pedagogic activity; these frameworks may even overlap the teacher’s talking without receiving a reprimand (Karvonen, Heinonen & Tainio 2018). The affordances of touch in school can be attributed in part to the fact that classrooms are often crowded places and thus participants may study, work and collaborate in close proximity. Within this context, the option of touching another participant can be only as far as the stretch of one’s hand or the leaning of one’s head or torso.

Previous research conducted on touch in educational settings has focused less on pedagogical and more on socio-relational work of haptic sociality. The distinction may be vague, too, as the use of haptic means may simultaneously achieve multiple actions. By haptic pedagogical work, we mean practices of touching that orient to teaching and working on academic content (e.g. a textbook). In contrast to early childhood education, students in primary and secondary education have typically been socialized to the normative practices of being a student (Macbeth 1990; Tainio 2007, 16-17; Margutti 2011), which involve postures that display an attention to the pedagogical content (Freebody & Freiberg 2000; Sahlström 2002, 48). In primary and secondary school, students may at times have to be haptically shepherded from one location of the classroom to another (Cekaite 2010), reminded of on-task focus or scaffolded on carrying out the tasks.

Thus far, among the studies on touch that contribute to pedagogical interaction, Heinonen, Karvonen and Tainio (2020) identify two types of pedagogical touch. The first is to help students to perform a task; and the second is to perform the socio-relational work that enables on-task behavior. Jakonen and Niemi (this issue) analyze how touch is used among primary school peers to manage participation in a pedagogic task. In particular, they show how participants use touch to regulate each other’s access to the learning materials, in their case a digital device. Kääntä and Piirainen-Marsh (2013) investigate manual guidance during a pedagogical task in a peer group. They demonstrate the extent to which touch serves as one of the modalities used with gesture as well as talking to establish a focal reference point in response to displaying an understanding of trouble with a task. Lindwall and Ekström (2012) report that in learning the manual skill of crocheting, touch is a vehicle of instruction within an ongoing pedagogical sequence. For Bergnehr and Cekaite (2018), touch is identified as educational when it is used to demonstrate and exemplify a learnable concept for language learners.

Our study continues the emerging line of research that examines touch as the right justification to achieve pedagogical goals. We contribute to the research by Heinonen et al. (2020) who analyzed touches on a recipient’s shoulder that initiate sequences of action. The sequences in their study were intended to encourage students to engage in on-task behavior. Here, we will demonstrate a recurrent and ordered sequence that achieves and directs the recipient’s attention to pedagogical content. The sequence emerges in ongoing pedagogical activity and consists of noticing and using touch as a summons, which is combined with pointing to direct a recipient’s attention to a focal content. The initiator may be either the teacher or the student, and the combination of touch and pointing gestures occurs both during student seatwork and teacher-fronted lessons. This interactional and emergent phenomenon addresses the theme of human-to-human touch in institutional settings by being situated in the context of classroom interaction, and within pedagogical activities.

2. Touch in managing joint attention

A prerequisite for both human interaction in general (Mondada 2009; Depperman 2013) and pedagogical interaction in particular (Mortensen 2009; Tanner 2017) is the achievement and management of joint attention. Indeed, the ability to share attention to an outside entity is a prerequisite for language learning (Tomasello 2010, 302). As C. Goodwin (2007) reported on a case analysis concerning family homework practices, joint attention can be achieved through the manipulation of objects and positioning of bodies. His analysis reveals how a father endeavors multimodally to shape the participation framework with his daughter to create a joint focus on a school assignment.

Previous research on ethnomethodological conversation analysis has approached joint focus as a practical matter of social interaction (Depperman 2013; Mondada 2014a; 2014b). Thus, this line of study highlights interactional practices that a participant can adopt to attract a recipient’s attention to either a speaker or an object. These practices involve both linguistic and embodied means of gaining a recipient’s attention. In his seminal paper on conversational openings, Schegloff (1968, 1080) observed a wide variety of different types of summons that range from a phone ring to terms of address, courtesy phrases, and embodied resources. These include waves of a hand or a light touch such as a tap on an intended recipient. Kidwell and Zimmerman (2007) offer a list of available manipulatives that very young children use when they try to gain a recipient’s attention to a mutual point of focus and act upon the contingencies of the moment. These manipulatives include one’s body, proximity, line of vision, gaze, and volume, such as lifting a toy to attract the adult’s attention to create a mutual point of attention. Mondada (2014b) emphasizes the importance of bodily alignment for joint attention. Tulbert and Goodwin (2011) discuss embodied arrangements of attention in family settings, and observe that caretakers attract children’s attention through the simultaneous use of multiple semiotic means, including touch.

Previous studies have reported that there is a wide range of practices available for participants to attract a recipient’s attention. These practices have been analyzed in both mundane and educational contexts. Our research contributes to this line of research by focusing on the work of touch in drawing a recipient’s attention to academic content in classroom settings. Heinonen et al. (2020) report on hand-on-shoulder touches that teachers utilize to help students focus on ongoing pedagogical activities. Cekaite (2016) reports on control touches that are used in educational settings to solicit and sustain a coordinated and attentive participation by a child. The present study offers further evidence that both teacher-to-student and student-to-teacher touch is a resource used to manage attention.

In contrast to the emphasis by Cekaite (2016) on the sustained and strongly controlling character of touches in reprimand sequences, we will report on touches that are light and short. Teachers and students use these touches not to control, but to direct attention. In fact, Cekaite (2016) also notices a light touch when a student summons a teacher. As a continuation of Heinonen et al. (2020) who report on hand-on-shoulder touch that achieves a pedagogically relevant participation framework, our analysis shows that the touch is followed by a pointing gesture towards the focus of pedagogical concern. Our objective is to demonstrate that a pedagogical focus is orchestrated as a methodical multi-party achievement through the dynamic use of a set of diverse semiotic fields.

In contributing to the body of research on managing joint attention, we examine how a joint pedagogical focus can be orchestrated through touch together with a set of other semiotic fields. For this purpose, we refer to Goodwin’s (2013) view on lamination of different layers of semiotic fields and their complex interplay in constructing intersubjectivity. In relation to this, Mondada (2014a; 2014b) traces the interactional roles of diverse modalities that include both linguistic and embodied resources to establish joint attention.

Specifically, Mondada’s concept of complex multimodal gestalt (CMG) refers to the dynamics and interdependence of multiple modalities (Mondada 2014a; 2014b; 2016; 2018). CMGs constitute arrangements in time and space that create emerging and changing positionings between participants, whose actions, relations, rights and the obligations related to them are negotiated multimodally. While verbal interaction generally exhibits a strong tendency for participants to speak one at a time (Sacks, Schegloff & Jefferson 1974), this preference organization for posture, gesture, and the manipulation of artifacts is somewhat different (Mondada 2018). The ordering of multiple modalities in a multimodal gestalt is not equivalent but the patterns of sequentiality may differ from those known for verbal interaction: Modalities other than linguistic and vocal represent “sequentially ordered simultaneities” (Mondada 2018, 94). The notion of a CMG involves synchronized resources and gives no priority to linguistic means over embodied ones. As an example of a CMG, Mondada (Mondada 2014a; 2014b) reports on a pointing gesture that is synchronized with body adjustments and language. Our research shows that touch opens up a sequence where pointing gestures also feature. Other resources that are utilized to direct attention to pedagogical content are gaze, talking and rearranging of bodies.

3. Data and method

We examine situations that occur in the midst of ongoing pedagogical activities in which the teacher gives the students an independent assignment, initiates an instructional interaction, or questions them. Within such activities, students are routinely held accountable for participating in an orderly way, such as directing their gaze towards the teacher or an object to achieve joint attention (Sahlström 2002). We observe that touch between a teacher and a student serves as a resource when directing attention to a task that has already been launched. According to our preliminary observations of the data, teacher-to-student touch is more common than student-to teacher touch, but we also present a case that features a student who engages in touch to direct the teacher’s attention to the pedagogically relevant content. Use of touch is part of a more complex contextual configuration (Goodwin 2000): It is preparatory for a subsequent pointing gesture.

The data are drawn from a corpus of approximately 150 hours of video-recorded lessons from primary and lower secondary education in monolingual and multilingual settings. The lessons were recorded with one to three cameras, and in some cases we use multiple angles in our analysis. All the data involve classes conducted as a group of 6-25 students who work under the supervision of at least one teacher. In addition, an assistant teacher is often present. Overall, our research team determined that intergenerational touch (i.e. teacher-to-student and student-to-teacher) is more common in primary school than in secondary school and with beginner-level language learners (Ahlholm & Karvonen, 2020). In these data, we observed touch between teachers and students, and identified sequences involving touch that result in a participant’s displayed attention to a pedagogical focus. Here we analyze three representative sequences. These cases originated from i) a transitional class with newly arrived immigrant children between 7 and 12 years old who are beginner-level language learners (excerpts 1 and 3) and ii) a Year 6 Finnish language and literature class where students between 11 and 12 years old study Finnish as their L1 (excerpt 2). The CMGs emerge during individual seatwork and teacher-fronted instruction.

The methodological framework of this study is multimodal conversation analysis (Goodwin 2000; Mondada 2006; Mondada 2009; Mortensen 2012; Deppermann 2013). This method allows us to consider attention as a practical challenge that can be solved through coordinated action. Furthermore, attention (and cognition more generally) is understood as publicly available in the details of embodied interaction through the visibility of gaze direction, adjustment of bodies, material artifacts, and the use of gestural and tactile resources. The analysis thus describes how the modalities are mobilized to achieve a purpose, such as a focus on pedagogical content, within a pedagogical task. The presentation of the data follows the CA approach (Hepburn & Bolden 2013), enriched with multimodal annotations (Mondada 2018). The transcriptions are complemented by analytic drawings and video clips to provide a synthetic perspective on the multimodal gestalt and on the ecology of action in context (Mondada 2018; Albert et al. 2019).

4. Analysis

We report on three analyses of intergenerational touch in classroom interaction that initiated a sequence of action to achieve a pedagogical focus of attention. The first two are teacher-initiated, whereas the third is student-initiated. Moreover, the first occurs during student seatwork, and the second and third occur during a teacher-fronted lesson. In all cases a pedagogical activity is underway. In the analyzed classrooms, the spatial configuration is organized in a way that allows the teachers to move around freely (see Jakonen 2018). During lessons, teachers and assistant teachers usually walk around the classroom, whereas students are predominately seated at their desks unless they are requested to move. This spatial configuration and mobility limitations provide the participants with asymmetrical resources for engaging in intergenerational touch: Teachers have more opportunities to initiate it. By moving within the classroom space, teachers may gain access to the students’ desks and bodies, but the students are also able to touch their teachers when they come near to the students. What the excerpts have in common is that touch serves a pedagogical goal in a sequence that establishes joint focus on pedagogical content in the classroom.

4.1 TEACHER-TO-STUDENT TOUCH DIRECTING ATTENTION TO PEDAGOGIC FOCUS DURING INDIVIDUAL SEATWORK

Teachers not only instruct and give assignments, they also observe what transpires in the classroom, and their monitoring of their students’ conduct can be understood as professional vision (Goodwin 1994). In other words, they see and interpret students’ actions in relation to their pedagogical framework, take notice of them, and act accordingly (Lachner, Jarozka & Nückles 2016). When they act, they may make use of professional embodiment, such as their body to approach a student in order to support a task (Jakonen 2018). The first excerpt from a transitional class consists of students who are newly arrived immigrants. In it, the teacher observes a student’s conduct and acts accordingly. She initiates a sequence with touch that produces a change in that student’s attention.

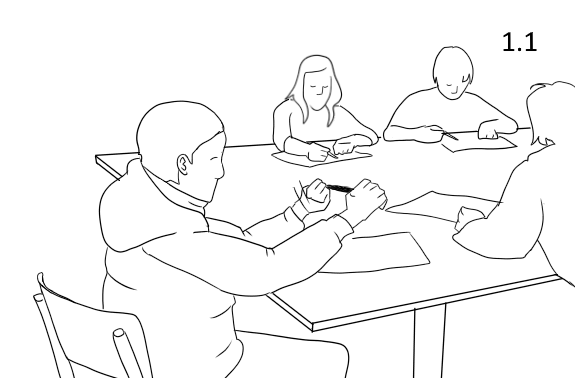

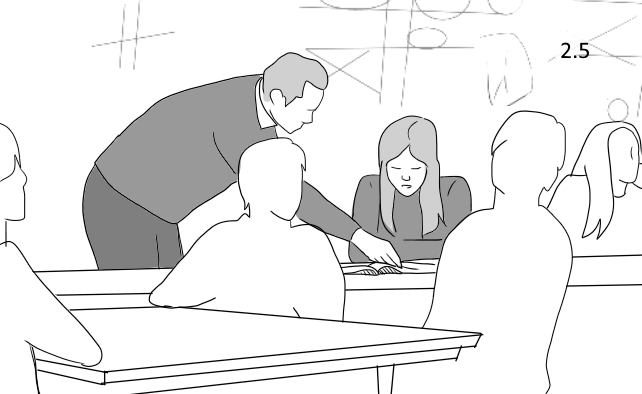

The students sit around a table in a configuration that allows them to interact with each other, but also offers them the possibility of paying attention to task materials and the instructional presentation technologies. While the goal of the lesson is to learn the anatomy of a human heart, currently each student is expected to draw a model of a heart from an image posted on the wall. The focal student, Paulo, has arrived only recently, and has very limited access to Finnish, which is the medium of instruction. As he sits at the table, he produces a barely audible utterance (probably in English) and fiddles with a pencil that he holds between his hands. There are two adults present: a class teacher and an assistant teacher. Paulo sits in the left corner of the image (Fig. 1.1, camera 1).

Figure 1.1 Paulo on the left fiddles with his pencil. Ebba and Eimar sit across the table and Rolan’s back is on the right. Angle from camera 1.

The situation involves overlapping participation frameworks: The assistant teacher reproaches Rolan (on the right side of Fig. 1.1) and Radimir (not visible) who are engaged in a playful physical fight with each other (line 2). We will focus on what occurs in overlap to this talking, which begins as the teacher approaches Paulo and touches him on the shoulder. The actions in which touch is embedded are described in turn in line 2. We provide the original verbal transcript in Finnish with an English translation beneath it. The transcript also indicates the focal participant’s hand gestures and touch (represented as ParH, where Par is short for the participant’s pseudonym and H is for hand), gaze directions (ParG) and embodied actions as well as posture (ParB) that occur simultaneously. In the descriptions of actions, “lh” refers to the left hand and “rh” to the right. Different symbols (*, %, ^) are used to indicate the onset of these non-vocal activities in relation to the talk and pauses. All excerpts below follow these conventions.

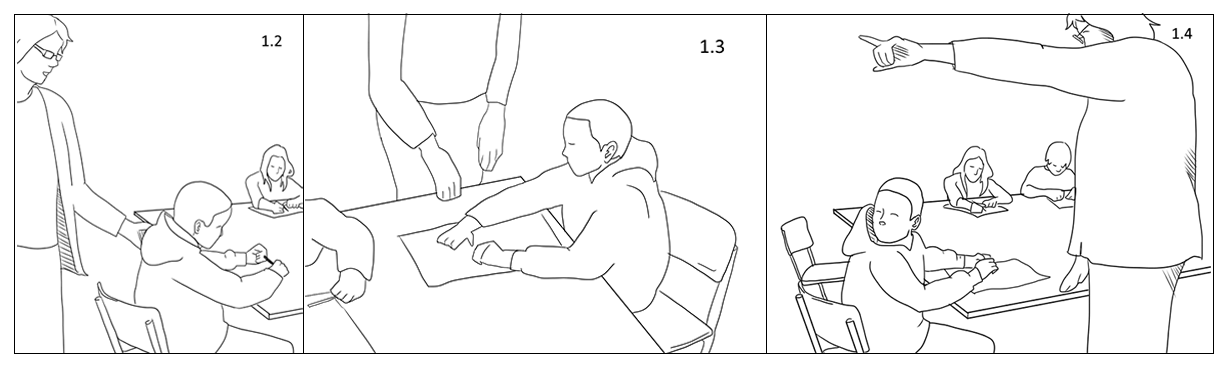

Open in a separate window During individual seatwork, there is an expectation of appropriate behavior: Although Paulo does not disturb others by fiddling with his pencil, he is ostensibly not working on the task (lines 1–2). The teacher has apparently noticed Paulo as she approaches him. The teacher’s approach catches Eetu’s attention (glance in line 2), and he summons her (line 3).The teacher, who is now visible in the video, does not respond to Eetu but maintains her gaze on Paulo while she reaches with her hand towards Paulo’s shoulder and touches it in a stroking manner (Fig. 1.2, camera 1). This touch is launched toward a neutral body part (see Suvilehto et al. 2015) that is also the student’s closest body part. The direction of the stroke is similar to the teacher’s walking direction. She then withdraws her hand and walks around the boy. Standing to Paulo’s right (left in Fig. 1.3, angle from camera 2), she suggests that he moves his seat to be able to see the model on the wall. She taps on the table and thus indicates the place for him to sit (line 4). These embodied actions that include touch orient the child to the preconditions of fulfilling the task - the ability to see the model image for the drawing task, as the teacher explains in her next turn (line 6). In this sequence, the teacher synchronizes her embodied actions, including her body adjustment, gaze and gestures. The teacher’s recommended relocation for the student is indicated by a tap on the table, which is produced simultaneously with the deictic phrase tässä näin (‘right here’, line 4, Fig. 1.3), and followed by a pointing gesture toward the location of the model image (line 6, Fig. 1.4).

Figures 1.2-1.4. The teacher strokes Paulo to attract his attention (1.2, camera 1), walks around him to indicate a location where to sit (1.3, camera 2), and finally makes a pointing gesture to indicate the pedagogical content (1.4, camera 1).

Responding to the stroke on his shoulder, Paulo starts to look at the teacher and twists his body to direct his gaze in the direction of the teacher’s pointing gesture. This postural body torque displays a management between more than one course of action (Schegloff 1998, 541): Paulo’s lower position orients to the study position but his torso and head align to the pointing by the teacher. After completing her pointing gesture, the teacher orients to other students, particularly Eetu (lines 8-10). At the beginning of this, Paulo remains seated. He returns to his initial position (line 8), then places his sheet of paper and pencil in his right hand, twists to the right and leaves the desk (lines 9-10). His actions suggest that he has only partly understood the teacher’s instruction: he gets up out of his seat and walks to the model image instead of taking the seat indicated by the teacher.

The individual task provides a pedagogical agenda and expected activity: drawing an image from a model. The teacher monitors the students’ work regarding the task and uses embodied means to direct Paulo’s attention to the materials provided. These means involve touch, followed by talking that is accompanied by a complex series of deictic gestures: first, tapping on the table; and second, pointing towards the model on the wall. These means lead to a change in the student’s display of attention.

The teacher’s touch on Paulo’s shoulder is deployed to gain his attention as a preliminary action before to re-orientating the child’s body to face towards the wall, which itself is a necessary orientation to carrying out the task. In addition, this touch resembles an encouraging touch: it is enacted with a soft, stroking or rubbing manner, which is typical of various kinds of positive affective touches (Burdelski this issue; Cekaite & Holm Kvist 2017; Guo et al. this issue; Raudaskoski this issue). While the touch does serve as an attention-getting device, it may also comfort Paulo who might feel confused and lost. The teacher is well aware that Paulo is in the early stages of learning Finnish. Thus, he is not treated as having disobeyed the teacher’s instructions or classroom norms, but merely as being unaware of how to proceed with the task.

During the period of time between the teacher’s touch and her subsequent gesture and accompanying talking, the language learner is allowed time to adjust his attention. Moreover, the teacher readjusts her body next to the seat that she suggests Paulo could take. She enables herself to be in close proximity to that seat and uses taps on the table in front of it to indicate the location where Paolo should move to. In relation to the following pointing, the teacher and the student are located in a manner that allows them to monitor each other frontally and to direct their attention to content relevant to the pedagogical task.

In this excerpt, the teacher’s touch is embedded within a larger project of individual seatwork. We can observe that touch is primarily used as a summons to attract attention, leading to a referring action that utilizes a pointing gesture to indicate the content that is to be attended to. This pointing gesture also directs the recipient (Paulo) to orient his gaze in another direction (almost 180 degrees behind him, in a kind of body torque, as suggested above). What we have witnessed here is a CMG that utilizes touch accompanied by talking and posture readjustment, a tapping and pointing gesture, which produce a change in the target student’s attention. Touch also afforded a parallel participation framework without disturbing the other ongoing framework in which the assistant teacher is speaking – an affordance of touch that is also reported elsewhere (Heinonen, Karvonen & Tainio 2020; Karvonen, Heinonen & Tainio 2018).

4.2 TEACHER-TO-STUDENT TOUCH ACHIEVING ATTENTION TO PEDAGOGIC FOCUS WITHIN TEACHER-FRONTED ACTIVITY

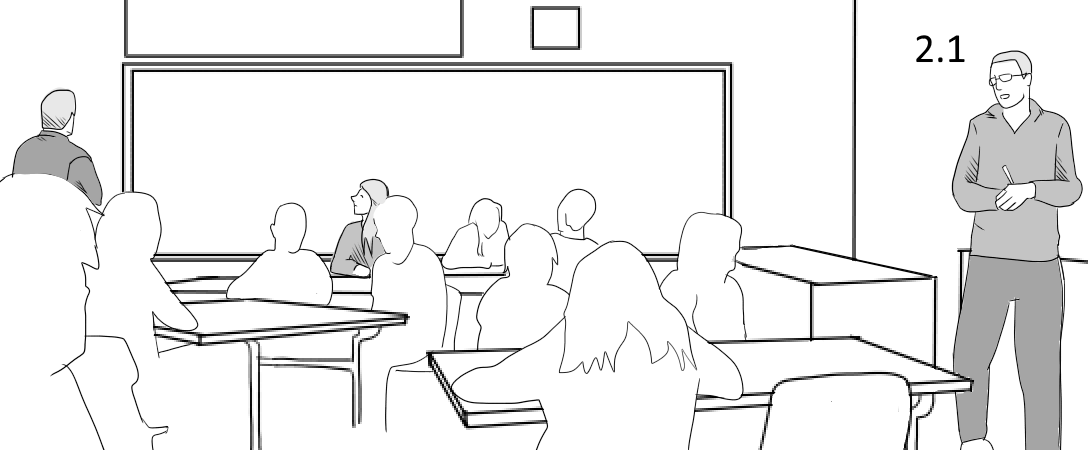

A second excerpt features a class of students from year 6 (11-12 years old) who are studying Finnish grammar. Similar to excerpt 1, they sit around a table in a configuration that allows them to interact with each other, but also enables them to pay attention to task materials and the instructional presentation technologies. The majority of the students are native Finnish speakers. The instruction is organized around the canonical teacher-led pedagogical sequence, IRE, with the teacher initiating (I), one of the students responding (R), followed by the teacher’s evaluating the response (E) (Kääntä 2010; Mehan 1979; Seedhouse 2004). For classroom interaction, it is typical that even when the students are expected as a cohort to display appropriate attention, not all students attend to their teacher’s instruction (Sahlström 2002). In these situations, one recurring practice is that an assistant teacher intervenes to resolve the lack of an individual student’s participation (Ahlholm & Karvonen 2020). This is where we encounter the touch that is used to initiate the sequence to direct the recipient’s attention.

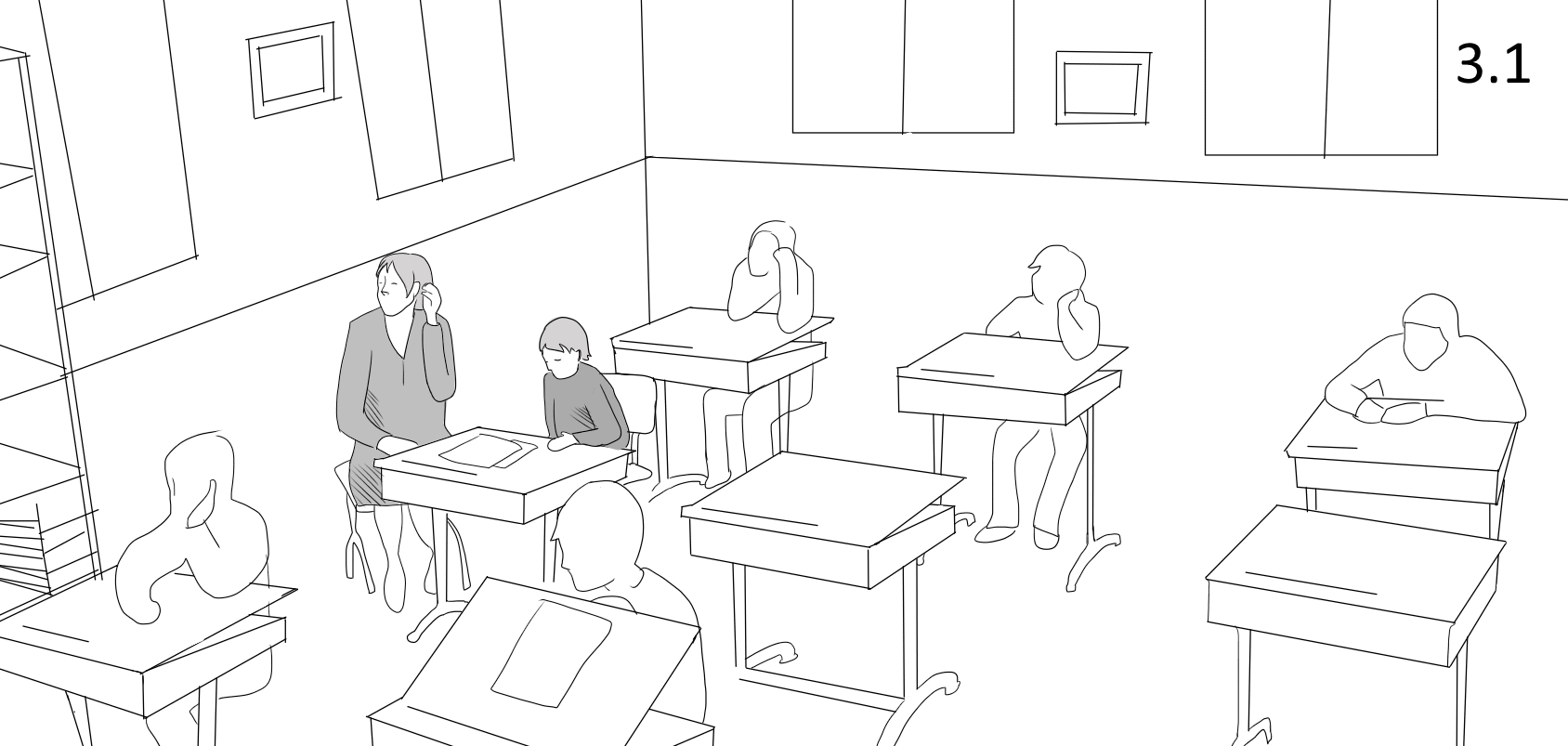

In excerpt 2, the primary teacher (standing on the right in Figure 2.1, shadowed) carries out the IRE-based instruction. The lesson is on the Finnish case system, and the teacher uses the textbook to draw the students’ attention to noun suffixes. The textbook layout uses the color red to mark these endings. The students sit with their textbooks open in front of them, and the majority of them assume a posture that allows them to see the textbook page. The page is also projected on a screen, which provides another option for attending to the pedagogical content. The assistant teacher (standing on the left, facing the wall) waits to be of assistance. The focal student, Anna, sits at the back (Fig. 2.1, shadowed). Instead of attending to her textbook or the projection on the screen behind the primary teacher, Anna’s head and gaze are turned towards the assistant teacher (for reasons that are not inferable from the video).

Figure 2.1. The embodied spatial organization in excerpt 2. The focal participants appear in grey and from the left are the assistant teacher, Anna and the teacher.

Open in a separate window

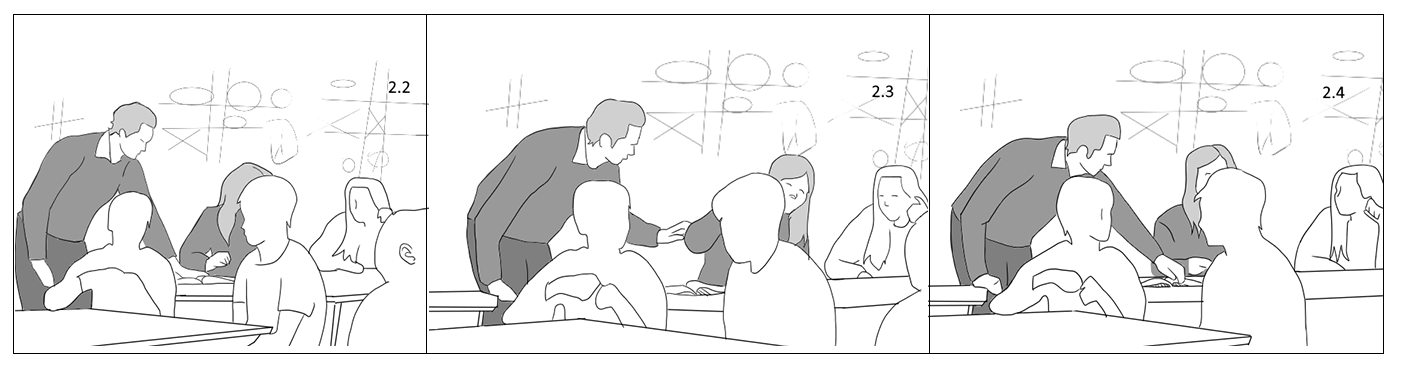

Figure 2.2-2.4 The assistant teacher indicates the focal point in the learning materials (2.2), monitors Anna’s attention and uses touch to attract her attention (2.3), and re-indicates the point while monitoring at the same time (2.4).

The excerpt begins with the teacher’s preface that announces that the next question will ‘come as a bomb’ (line 1). With this idiosyncratic expression, he instructs all students to listen attentively because he might allocate the turn to anyone (Karvonen, Tainio, Routarinne & Slotte 2015; Karvonen, Tainio & Routarinne 2018). While the teacher makes this preliminary announcement (Schegloff 2007, 28–29), the assistant teacher turns to Anna, and begins to move toward her. In a progression of the pedagogical interaction, Anna’s posture has become observable as being non-attendant to the pedagogical focus, which is in the textbook page (Figure 2.1).

In the middle of the primary teacher’s preface, as the assistant teacher approaches Anna, Anna’s gaze meets the assistant teacher’s gaze and this leads to a moment of mutual gaze. Soon after, Anna shifts her gaze away, and then turns towards the page of her book. The assistant teacher’s gaze follows the trajectory of Anna’s gaze towards the page. In the first phase of this excerpt, the approaching assistant teacher appears at first to affect Anna’s focus. (Line 1).

The duration of the assistant teacher’s approach to Anna lasts as long as it takes the teacher to finish his preface. In this sense, we can observe that the assistant teacher’s embodied action is adjusted to and synchronized with the teacher’s verbal action. At the same time, Anna turns to her peer sitting next to her (Bea) and taps Bea’s upper arm (line 2). When the primary teacher begins his next turn with a structure that projects a question (Mikä on ‘What is’, line 3, Figure 2.2), the assistant teacher has adjusted his body so that he is next to Anna. He monitors her face and extends his left hand to point to the textbook page in front of Anna and to indicate where she can look for an answer. Anna continues to be preoccupied with Bea; Anna turns her body away from Bea, making a pointing gesture over her right shoulder to indicate something to Bea, whose gaze follows. During these actions, Anna is ostensibly not attending to the pedagogic task. She also manages to disengage her peer, who now attends to Anna instead of the pedagogical content.

As a follow-up to Anna’s displayed lack of focus on the academic agenda, the assistant teacher taps Anna’s elbow in the middle of the teacher’s question (Fig. 2.3, line 4). This tap may have been intended to target her upper arm, but when Anna raises her hand, her elbow meets the trajectory of the assistant teacher’s left hand. While the teacher completes his question, the assistant teacher makes another pointing gesture to the open textbook page in front of Anna, and again monitors the response by looking at Anna’s face (Fig. 2.4, end of line 4). When the teacher starts to allocate the respondent (line 7), he repeats the tap but uses his right hand. By switching his hand, he also adjusts his posture and twists his upper body to create a triangular formation so that the participants are able to see each other’s faces as well as the textbook page (line 7, Fig. 2.5). Anna finally assumes what we refer to as a study position, and her posture displays that she is looking at the textbook.

Figure 2.5 The assistant teacher manages to direct Anna’s attention to pedagogical content, the textbook.

Excerpt 2 instantiates the multiple and simultaneous participation frameworks in which touch is embedded within a teacher-fronted activity. Besides the teacher-led and agenda-driven participation framework between the teacher and the student cohort, the assistant teacher constructs a parallel participation framework that supports the pedagogical sequence and directs one student’s attention toward the content. At the same time, the student interacts with her peer to build an off-record participation framework. In this micro-level competition for student focus, a short, soft tap on the recipient’s elbow is used as an attention-getting device. This is followed by a pointing gesture that attempts to draw attention to the pedagogical content in the textbook. This pointing gesture indicates where to retrieve information to answer the teacher’s question.

During the sequence, the assistant teacher’s touch followed by his pointing gesture is only one means to direct attention to the task. These movements serve to remind the student of a classroom rule that they should remain focused when the teacher is talking to them (Freebody & Freiberg 2000). The sequence in which touch is one of the multimodal means emerges only after the pedagogical sequence is projected when Anna’s body and gaze direction are observably displaying a failure to attend to the pedagogic task. Thus, the adult-initiated touch also manifests itself as an embodied reproach, referring to the classroom norm, and serves to enforce the rules (Jakonen 2016). Reproaches in the classroom are designed to consider the student’s familiarity with the violated rule (Margutti 2011), and for this reason the assistant teacher’s touch on the student’s elbow is sufficiently clear for the recipient and needs no verbal explanation.

In extract 2, the classroom instruction was distributed among multiple participants within overlapping participation frameworks: The primary teacher instructed mainly verbally with the help of an overhead projection, whereas the assistant teacher employed gestural and tactile resources when a student’s attention was observably not on task. The assistant teacher’s touch attracted the student’s attention, which was a prerequisite to direct it. Pointing then followed, and the configuration of these means achieved the student focus on the task. Overall, the sequence is even more complex because it is connected to the temporal unfolding of instruction, and it is sequentially organized and multilayered, involving visual monitoring and body adjustment to meet the contingencies of the moment. In its context, the touch plus pointing gestalt occurred within competing simultaneous practices carried out by different participants and afforded non-vocal communication when the teacher has the floor. The teacher and assistant teacher seem to be playing as an ensemble.

4.3 STUDENT-TO-TEACHER TOUCH ACHIEVING ATTENTION TO PEDAGOGIC FOCUS DURING TEACHER-FRONTED ACTIVITY

In contrast to the previous two excerpts, the analysis of excerpt 3 focuses on a student-initiated touch of a teacher. Here, we encounter the same transitional class as in excerpt 1. The lesson occurs at the beginning of the academic year. That is, all students are just beginning to learn the language of instruction, Finnish. This time they sit individually in rows in order to see and hear the teacher’s instruction. In general, in our data this spatio-material configuration leads less frequently to tactile contact between participants than when the students sit around tables. The teacher has implemented a morning routine that entails naming the day, making observations about the weather, verbalizing these observations and deciding on what a paper doll should wear for the day. Students are encouraged to use textbooks to search for vocabulary. The pedagogical motivation for this routine is to create a play-like participatory space for the supported rehearsal of everyday vocabulary. In addition to the class teacher, two assistant teachers are present. One of them has seated herself next to the youngest of the students, Max. As the youngest in the class, he is also a beginner in literacy, receiving special adult assistance.

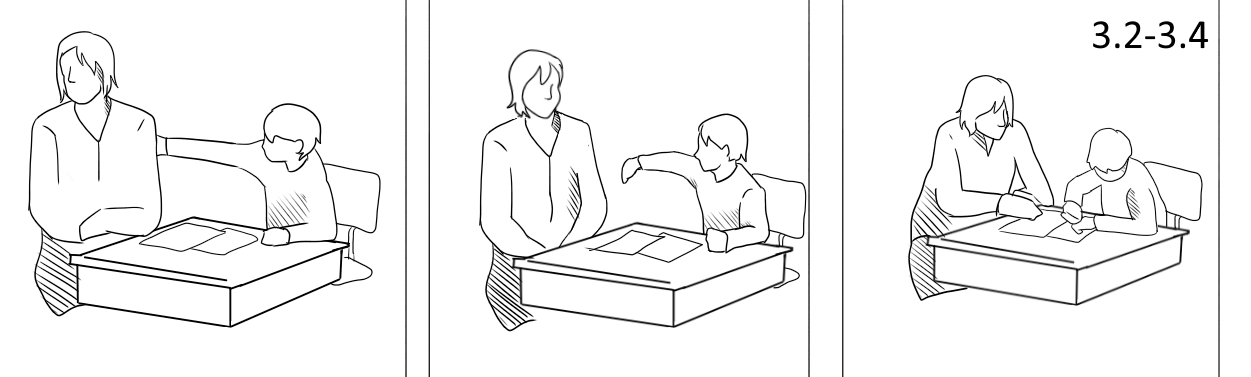

Prior to this excerpt, Max and the assistant teacher listened to the primary teacher’s talk. During this talk, they also engaged in a private nonverbal interaction. The assistant teacher has searched for the relevant page in the book for Max, and it is now open in front of him. While the assistant teacher displays that she is listening to the teacher talking, Max begins to study the page (Fig. 3.1 below). The transcript captures the teacher’s evaluation within one of the IRE cycles that is used to elicit suggestions for dressing a paper doll (line 1). In this case, the predominately nonverbal interaction between Max and the assistant teacher is more important than the talk-in-interaction.

Figure 3.1 The assistant teacher is seated next to the youngest student, Max.

Open in a separate window

Figures 3.2-3.4 Max reaches to the assistant teacher’s upper arm. As a consequence, they both direct their gaze to the contents in Max’s book.

During the pause that follows the teacher’s evaluation (line 2), Max uses his right hand to reach and tap the assistant teacher’s upper arm (Fig. 3.2). In response, the assistant teacher turns her gaze to Max (Fig. 3.3). As soon as Max attracts her attention, his gaze shifts again to the book, and he points to it repetitively (Fig. 3.4). The assistant teacher turns to the page and begins pointing at it (lines 3–4). When the primary teacher utters an assessment that further comments on the color of the first choice of clothing (l. 5), the assistant teacher straightens up, and makes a gesture of putting on a scarf (Fig. 3.5). Max responds to this pretend action by acknowledging it with a nod and making a pointing gesture to the page in front of him.

Figure 3.5 The assistant teacher pretends to put a scarf on.

The participation roles in excerpt 3 differ from those in the previous excerpts. A student initiates a complex multimodal gestalt to create a joint focus of attention that is relevant to the pedagogical interaction currently underway. Similar to other examples, here the CMG consists of a touch that draws the recipient’s attention that is further directed to the relevant pedagogical content, which is the textbook page in front of the student. By using touch to attract the assistant teacher’s attention, Max is able to initiate an overlapping participation framework during the teacher-fronted activity. In this particular situation, the overlapping action forms an embedded insertion subsequence (Schegloff 2007, 97-117) within the ongoing pedagogical activity. The student-initiated touch displays an intense orientation to the ongoing learning activity, as well as the student’s eagerness to present his skills. This sequence resembles previous cases in that it consisted of two parts. The first was touch, which was used as an attention-getting device, and the second is a gesture, which was used as a referring action to indicate the focal point of attention and establishes it in reference to the pedagogical content. This technique was used to achieve a pedagogical focus of attention.

5. Concluding discussion

We have examined a sequence initiated with touch that directs attention to an object of focus in a sequential context where a pedagogical activity was underway. The type of pedagogical formation varied: In excerpt 1, the task involved individual seatwork whereas in excerpts 2 and 3 there was teacher-fronted questioning based on the IRE sequences. Both teacher-to student (ex. 1 & 2) and student-to-teacher sequences were observed (ex. 3). The analyzed sequences consisted of at least two actions: The initial action prepares for the following action. Touch was used to draw the recipient’s attention, whereas a pointing gesture subsequently directed the attention towards the object. The pointing gesture located the pedagogical content in the environment to be attended to. As we argued, the configuration of touch and pointing gesture constitutes a complex multimodal gestalt (CMG). The observed sequential body technique fosters pedagogical activities and on-task behavior.

Depending on the contingencies of the moment, other resources in the studied sequences included the adjustment of bodies, talking and access to material artifacts. In excerpt 1, the teacher’s movement of her body to the location where the boy being addressed should be sitting and the tapping on the table were crucial. On the one hand, as in excerpt 1, the initiator of the multimodal configuration may also use verbal means. On the other hand, as in excerpt 2, the person who uses the touch and pointing CMG can work in concert with an unfolding verbal action that is conducted by another participant. During excerpt 2, the embodied means of directing a student’s attention were tailored to address the trajectory of the teacher’s verbal preface as well as the initiation of a question. As a local contingency, both in excerpts 1 and 2, the target student’s neglect of the pedagogical agenda was observable to a teacher’s professional vision (see Lachner et al. 2016): The teacher (or an assistant teacher) monitored the students and initiated the CMG to manage a student’s lack of attention. Finally, in excerpt 3, a student who was intensively attending to the pedagogical frame deployed the CMG to receive assistance from the assistant teacher sitting next to him.

The attention-directing touches cooperate with talking and their timing was designed to fit the trajectory of the ongoing sequence and its multiple participation frameworks. In excerpt 2, the timing of the assistant teacher’s approach, pointing actions and touching were particularly tailored to meet the primary teacher’s unfolding talking as well as the student’s orientation to the peer sitting next to her. This sequentially organized multimodal gestalt can also be achieved without talking, making it a useful resource in the ecology of managing parallel activities in multi-party interactions, such as interactions that occur in a classroom.

Although touch is exceedingly clear in indicating an addressee, it does not require voice and is therefore less disruptive when another person is occupying the floor. This technique applies to the polyphony of parallel activities that typically occur in classrooms, and it enables the orchestration of these parallel actions and simultaneous participation frameworks. It is of note that in all the classes observed at least two adults were present: the primary teacher and one or two assistant teachers. In excerpt 3, the sequence formed a nonverbal and private two-party insertion into the whole class pedagogical action.

Attention-getting touches were directed to on relatively neutral parts of the receiving body, such as the elbow, upper arm or shoulder (also Heinonen et al. 2020; Suvilehto et al. 2015). The location of the touch was tailored to the availability of the interlocutors’ bodies. The exact location therefore appears to be dependent on the participants’ proximity and position. For example, in excerpt 1, the teacher gently stroked the student’s shoulder while passing by, and subsequently placed herself in a location visible to the student, allowing for the next pointing action. Excerpt 2 featured the assistant teacher, who directed the attention-getting touch to the recipient’s elbow, because the recipient was involved in another action that involved her raising her arm at the same time as the assistant teacher attempted to attract her attention. During excerpt 3, the student tapped the assistant teacher’s upper arm that is nearest to his hand.

The practice of attention-getting touch may originate from mundane interactions. Schegloff (1968) mentions it as one of the available practices to get a recipient’s attention. In comparison to sustained and strongly controlling teacher touches on students that hold a student’s attention (Cekaite 2016), the ones studied in this article were soft, especially when the teacher was the initiator. The softness of these touches, and their capacity to solicit a recipient’s attention, indicates that they are recognized as seeking attention. A similar conclusion was drawn in an earlier study where peer-to-peer touches leading to a recipient’s attention were described as a conventionalized method of getting attention (Karvonen, Heinonen & Tainio 2018).

The phenomenon of joint focus of attention is particularly relevant for instructional encounters. Forming a joint focus of attention is often a prerequisite for engagement in a pedagogic task. Thus, in order to involve students in learning activities, the teacher needs to direct the students’ attention to contents – be they spoken, written on a blackboard or whiteboard, or printed in a textbook. Also, a student may need to get the teacher’s attention to receive assistance, as in extract 3. Thus, managing attention is a necessary condition for a successful attempt to impact students’ encounters with pedagogical content. The achievement of a pedagogically relevant focus is a social and practical matter with touch constituting one of the useful techniques. Communicative resources such as touch, gestures and proxemics are used in pedagogically expedient ways, in line with verbal acts. According to Heinonen et al. (2020), a hand-on-shoulder touch is a resource for constructing a pedagogically relevant participation framework. Our analysis contributes to this line of research by further specifying how the touch is coupled with a pointing gesture. The CMG further specifies the focus of pedagogic concern of that moment. Additional research is needed on touch in school to determine useful pedagogic applications for pre-service and in-service teachers to enhance their awareness of touch in classroom interactions.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments that helped us to rewrite the article, and Matt Burdelski for his endeavors in discussing the details of study. The study was conducted as part of the project Touch in School funded by the Kone Foundation.

References

Ahlholm, M. & Karvonen, U. (2020). Episodes of touch between classroom assistant and student in preparatory education. Presentation in NERA 2020, Rethinking the futures of education in the Nordic countries. University of Turku, 4.3.2020.

Albert, S., Heath, C., Skach, S., Harris, M., Miller, M., & Healey, P. (2019). Drawing as transcription: how do graphical techniques inform interaction analysis? Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v2i1.113145

Bergnehr, D. & Cekaite, A. (2018). Adult-initiated touch and its functions at a Swedish preschool: controlling, affectionate, assisting and educative haptic conduct. International Journal of Early Years Education, 26(3), 312-331. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2017

Burdelski, M. (2010). Socializing politeness routines: Action, other-orientation, and embodiment in a Japanese preschool. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(6), 1606–1621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.11.007

Burdelski, M. (2020). Embodiment, ritual, and ideology in a Japanese-as-a-heritage-language preschool classroom. In M. J. Burdelski & K. M. Howard (eds.), Language socialization in classrooms: Culture, interaction and language development (pp. 200-223). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Burdelski, M. & Mitsuhashi, K. (2010). “She thinks you’re kawaii”. Socializing affect, gender and relationships in a Japanese preschool. Language in Society, 39, 65–93. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404509990650

Cekaite, A. (2010). Shepherding the child: Embodied directive sequences in parent–child interactions. Text & Talk: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Language, Discourse & Communication Studies, 30(1), 1-25.

Cekaite, A. (2015). The coordination of talk and touch in adults’ directives to children: Touch and social control. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 48(2), 152-175. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2015.1025501

Cekaite, A. (2016). Touch as social control: Haptic organization of attention in adult-child interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 92, 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2015.11.003

Cekaite A. & Kvist Holm, M. (2017). The comforting touch: Tactile intimacy and talk in managing children´s distress. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 50(2), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2017.1301293

Deppermann, A. (2013). Multimodal interaction from a conversation analytic perspective. Journal of Pragmatics, 46(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.11.014

Freebody P. & Freiberg, J. (2000). Public and pedagogic morality: The local order of instructional and regulatory talk in classrooms. In Hester S. & Francis D. (Eds.), Local educational order. Ethnomethodological studies of knowledge in action (pp.141–162). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Charles, C. (1994). Professional vision. American Anthropologist, 96(3), 606-633.

Goodwin, C. (2000). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 32, 1489–1522. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00096-X

Goodwin, C. (2007). Participation, stance and affect in the organization of activities. Discourse and Society, 18(1), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926507069457

Goodwin, C: (2013). The co-operative, transformative organization of human action and knowledge. Journal of pragmatics, 46(1), 8-23.https://doi-org.ezproxy.utu.fi/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.09.003

Goodwin, M. H. (2017). Haptic sociality. In C. Meyer, J. Streeck & J. S. Jordan (Eds.), Intercorporeality: Emerging socialities in interaction (pp. 73–102). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goodwin, M. H. & Cekaite, A. (2018) Embodied family choreography: Practices of control, care, and mundane creativity. London: Routledge.

Heinonen, P., Karvonen, U. & Tainio, L. (2020). Hand-on-shoulder touch as a resource for constructing a pedagogically relevant participation framework. Linguistics and Education, 56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2020.100795

Hepburn, A., & Bolden, G. B. (2013). The conversation analytic approach to transcription. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.) The Handbook of Conversation analysis (pp. 57–76). Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Jakonen, T. (2016). Managing multiple normativities in classroom interaction: Student responses to teacher reproaches for inappropriate language choice in a bilingual classroom. Linguistics & Education, 33, 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2015.11.003

Jakonen, T. (2018). Professional embodiment: Walking, re-engagement of desk interactions, and provision of instruction during classroom rounds. Applied Linguistics, 0/0, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amy034

Karvonen, U. Heinonen, P. & Tainio, L. (2018). Kosketuksen lukutaitoa. Konventionaaliset kosketukset oppilaiden välisissä vuorovaikutustilanteissa. In L. Lehti, P. Peltonen, S. Routarinne, V. Vaakanainen & V. Virsu (Eds.) Uusia lukutaitoja rakentamassa. Building New Literacies (pp. 159–183). AFinLA Yearbook, 75(1), Jyväskylä. https://doi.org/10.30661/afinlavk.69257

Karvonen, U., Tainio, L., Routarinne, S. & Slotte, A. 2015. Tekstit selitysten resursseina oppitunnilla. Puhe ja kieli, 35(4), 187-209. Retrieved from https://journal.fi/pk/article/view/55388

Karvonen, U., Tainio, L. & Routarinne, S. 2018. Uncovering the pedagogical potential of texts: Curriculum materials in classroom interaction in first language and literature education. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 17, 38-55. https://doi-org.ezproxy.utu.fi/10.1016/j.lcsi.2017.12.003

Kidwell, M., & Zimmerman, D. (2007). Joint attention as action. Journal of Pragmatics, 39(3), 592–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2006.07.012

Kääntä, L. (2010). Teacher turn-allocation and repair practices in classroom interaction: A multisemiotic perspective. Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities, 137, Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

Kääntä, L. & Piirainen-Marsh, A. (2013). Manual Guiding in Peer Group Interaction: A Resource for Organizing a Practical Classroom Task. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 46(4), 322-343. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2013.839094

Lachner, A., Jarodzka, H., & Nückles, M. (2016). What makes an expert teacher? Investigating teachers’ professional vision and discourse abilities. Instructional Science, 44(3), 197-203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-016-9376-y

Lindwall, O. & Ekström, A. (2012). Instruction-in-interaction: The teaching and learning of a manual skill. Human Studies, 35(1), 27-49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-012-9213-5

Macbeth, D. (1990). Classroom Order as Practical Action: the making and un-making of a quiet reproach. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 11(2), 189–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142569900110205

Margutti, P. (2011). Teachers’ reproaches and managing discipline in the classroom: When teachers tell students what they do ‘wrong’. Linguistics and Education, 22(4), 310–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2011.02.015

Mehan, H. (1979). Learning lessons. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mondada, L. (2006). Participants’ online analysis and multimodal practices: projecting the end of the turn and the closing of the sequence. Discourse Studies, 8, 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445606059561

Mondada, L. (2009). Emergent focused interactions in public places: A systematic analysis of the multimodal achievement of a common interactional space. Journal of Pragmatics, 41(10), 1977-1997.

Mondada, L. (2014a). Pointing, talk, and the bodies. In M. Seyfeddinipur & M. Gullberg (Eds.). From gesture in conversation to visible action as utterance: Essays in honor of Adam Kendon (pp. 95-124). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Mondada, L. (2014b). The local constitution of multimodal resources for social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 65, 137-156.

Mondada, L. (2016). Challenges of multimodality: Language and the body in social interaction. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 20(3), 336-366. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.1_12177

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85-106. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.141387

Mortensen, K. (2009). Establishing recipiency in pre-beginning position in the second language classroom. Discourse Processes, 46(5), 491-515, https://doi.org/10.1080/01638530902959463

Mortensen, K. 2012. Conversation analysis and multimodality. In J. Wagner, K. Mortensen & C.A. Chapelle (Eds.) The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics (pp. 1061–1068). Malden MA: Wiley-Blackwell. DOI: 10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0212

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696–735. https://doi.org/10.2307/412243

Sahlström, F. (2002). The interactional organization of hand raising in classroom interaction. The Journal of Classroom Interaction, 47-57.Schegloff, E. A. (1968). Sequencing in Conversational Openings. American Anthropologist, 70(6), 1075-1095.

Schegloff, E. A. (1998). Body torque. Social Research, 65(3), 535-596.

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence Organization in Interaction. A Primer in Conversation Analysis. Cambrindge: Cambridge University Press.

Seedhouse, P. (2004). The Interactional Architecture of the Language Classroom. A Conversation Analysis Perspective. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Streeck, J. (2013). Interaction and the living body. Journal of Pragmatics, 46(1), 69-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.10.010

Suvilehto, J., Glerean, E., Dunbar, R., Hari, R., Nummenmaa, L., & Suvilehto, J. (2015). Topography of social touching depends on emotional bonds between humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(45), 13811–13816. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1519231112

Tainio, L. (2007). Miten tutkia luokkahuoneen vuorovaikutusta keskustelunanalyysin keinoin? [How to do Conversation Analysis in the Classroom?] In L. Tainio (ed.) Vuorovaikutusta luokkahuoneessa: näkökulmana keskustelunanalyysi (pp. 15-58). Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Tainio, L. (2016). Kiusoittelun kielioppi: nuorten elämää luokkahuoneessa. In A. Solin, J. Vaattovaara, N. Hynninen, U. Tiililä & T. Nordlund (Eds.) Kielenkäyttäjä muuttuvissa instituutioissa. Language user in changing institutions (pp. 20-42). AFinLA Yearbook 74. Retrieved from https://journal.fi/afinlavk/article/view/59718

Tanner, M. (2017). Taking interaction in literacy events seriously: a conversation analysis approach to evolving literacy practices in the classroom. Language and Education, 31(5), 400-417, https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2017.1305398

Tomasello, M. (2010). Social cognition before the revolution. P. Rochat (Ed.) Early Social Cognition. Understanding others in the First Months of Life (pp. 301-314). New York: Taylor & Francis.

Tulbert, E., & Goodwin, M. H. (2011). Choreographies of attention: Multimodality. In: J. Streeck, C. Goodwin & C. LeBaron (Eds.) Embodied interaction: Language and body in the material world (pp. 79-92). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.