Social Interaction.

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality.

2019 VOL.2 , Issue 2

ISBN: 2446-3620

DOI: 10.7146/si.v2i2.118041

Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Encouragement in videogame interactions

Heike Baldauf-Quilliatre (Lyon 2 University, ICAR laboratory)

Isabel Colón de Carvajal (ENS of Lyon, ICAR Laboratory)

Abstract

This paper explores how participants encourage each other in videogame interactions in private settings. It aims to contribute to a better understanding of encouragement as multimodal practice in videogame interaction. In the paper we focus especially on a comparison of encouragements and instructions and argue that they are used differently: encouragements show another sequence structure than instructions, occur in particular contexts and are characterized by a specific turn design. We consider two types of encouragements. First we analyze encouragements occurring after a display of demotivation and projecting indices of re-motivation of the co-participant. Then we show encouragements produced to incite the encouraged player to continue his ongoing gaming action. This type of encouragements occurs when the instructed action is already going on and it is characterized by lexical repetition and a particular rhythmicity. Our study draws on a corpus of 21h video recorded mostly multiplayer videogame interactions in French.

Keywords: videogame interactions, instruction, encouragement, action ascription, multimodality

1. Introduction

Video gaming constitutes a very popular social activity. Playing a video game involves a large variety of mediated digital interaction (Arminen, Licoppe & Spagnolli 2016) on a game console, a tablet, a smartphone, a computer or similar digital object. On the one hand, a single player can play alone or interact online with other participants. On the other hand, people can play together, similar to a board game, collaboratively or competitively, offline or online. Although research on videogames is abundant, ethnomethodology or conversation analysis has only recently taken an interest in the field. Whereas much prior research is focused on online videogames, analysis of interaction between (physically) co-present players who play side by side on one or more screens is less frequent (for a summary see Reeves, Greiffenhagen & Laurier 2017).

With regard to conversation analysis and its interests, previous studies have focused on the formation and ascription of actions in this particular participation framework, especially on assessments and instructions. They have shown the particular turn design of instructions or assessments in order to claim or reject agency, responsibility or expertise on the one hand (Mondada 2011, 2012, 2013) and to construct participation frameworks on the other (Baldauf-Quilliatre 2014a). They have explained how actions in the game have to be taken into account for explaining the sequential organization, as for instance responsive action to an instruction or a directive (Mondada 2012, 2013) or as choral co-productions (Colón de Carvajal 2011). They have also underlined the importance of temporality (Mondada 2011, 2013).

In our paper we would like to discuss a type of instruction (as NOW-directives; Vine 2009) whose main purpose is not to instruct a co-participant, but to encourage him. These actions are rather particular with regard to their turn format as well as to the structure of the sequence: they are produced when the instructed action is already being carried out (and not before the instructed action), they do not primarily show expertise or attribute responsibility and they are characterized by repetition and rhythmicity. Looking more closely, we have found similarities with fan chants in a football stadium (Brink 2001, Khodadadi & Gründel 2006, Brunner 2009, Burkhardt 2009), encouragements from a coach (Schilling 2001) or incitements described during powerlifting (Reynolds 2017a and b).

In an EMCA perspective, instructions are not single actions, but part of an instruction sequence which is characterized by the adjacency pair ‘instruction’/‘instructed action’ (Garfinkel 2002). Early work on instruction sequences dealt with its sequential, local and praxeological construction (e.g. Mehan 1979). With the development of workplace studies and the analyses of classroom interaction, new questions arose, concerning namely epistemics, agency or the negotiation of responsibility (e.g. Mondada 2012, Keevallik 2017, Rauniomaa 2017) as well as the temporal organization of the instruction sequence (Mondada 2013, 2017). A growing interest in multimodality and multi-activity puts the focus on non-verbal practices of instructing and/or accomplishing the instructed action (e.g. Keevallik 2010a, Tolins 2013). But in nearly all cases, the instruction systematically precedes the instructed action,[1] and analyses of interactions within a very high temporality (such as car racing, Mondada 2017; driving lessons, de Stefani & Gazin 2014; surgery, Mondada 2014a) have shown the finely tuned coordination between instruction/request and the instructed/requested action even in these “urging” sequences.

By contrast, the “instructions” we are interested in occur in a different sequence position and are not treated in the same way by the participants. Without a doubt, participants give instructions very frequently: they indicate what another player and/or avatar has to do in the game (task-setting requests, according to Deppermann 2015: 74) or, with regard to the avatar’s performance, indicate how the player could improve his avatar’s actions (corrective instructions). However, in other cases, it is not so much a matter of "what to do," or of "how to complete the task," but of motivating and encouraging the co-participant, whose main task is therefore not to complete the instructed action in a specific way. The general target of the action is to achieve an outcome in the game and the co-participant’s main objective is to carry this out; how, and to some extend if, he really gets there is secondary.

In this paper we will first present the data on which we base our analyses as well as the methodology we adopt (section 2). Then we will describe two types of encouragement as part of the players’ in-game interaction (Mondada 2012) which are related to onscreen events (section 3).[2] Our data show that encouragements can be used (a) to incite the co-participant to show more engagement and (b) to confirm the co-participant’s ongoing action. In both cases, the action projects displays of (re)engagement. In the last section we discuss encouragements as actions and explain why we consider them as different from instructions (section 4). Our argumentation is based on differences in epistemic stance (Heritage 2012), differences in the interactional project and therefore differences in sequence development.

The study aims to contribute to the understanding of videogame interactions on the one hand and to the understanding of action formation/action ascription on the other.

2. Data and Methodology

The video data used in this paper are part of two research projects conducted within the ICAR research laboratory in Lyon (France). The data consist of 21 hours of mostly multiplayer videogame interactions in families or peer groups which have been video-recorded with at least two different camera views: one on the players and the other on the screen. Since there is no camera focused on the controller, access to manual inputs on the controller is only partial. We therefore sometimes use an inferential interpretation with regard to our knowledge of the game and/or with regard to what is displayed on the screen.

In this study we adopt the fieldwork methodology as well as the analytical mentality developed in the fields of conversation analysis (Sidnell & Stivers 2012) and of interactional linguistics (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting 2001; 2017). Conversation analysis aims to capture audio and video data in order to make available, and thus analyzable, linguistic, multimodal and situational resources (gazes, gestures, movements, actions, objects, physical settings) which are relevant to the recorded interaction (Groupe ICOR 2006). It therefore allows the observation of the precise evolution in time and space of one or more gaming sessions, of the social and spatial interactions that are co-constructed by the players, and of the players’ actions in the game.

3. Instruction and Encouragement

Instruction sequences within an EMCA framework have been studied mostly, but not exclusively in the context of educational settings: in classrooms (Macbeth 2004; Jakonen 2018), in medical training settings (e.g. Svensson et al. 2009; Zemel & Koschmann 2011), in driving lessons (e.g. Deppermann 2018a and b), in sports interactions or training (e.g. Okada 2018; Simone 2018), in music or dance lessons (e.g. Keevallik 2010a; Tolins 2013; Stevanovic & Kuusisto 2018), in cooking courses (Mondada 2014b) or in knitting tutorials (Heinemann & Möller 2016). Less frequently, research has also been conducted in the context of workplace interactions (Goodwin 2003; Svensson, Heath & Luff 2007) or leisure activities (Mondada 2011).

The variety of settings has clearly shown that instructions as well as its responsive actions can be realized in very different ways. Keevallik, (2010a) for instance, describes body quotations in dance lessons which “serve to give the students access to their own performance and establish a ground for adjustments” (ibid.: 424). Tolins (2013) remarks in a similar way on quotations in music lessons: “These sorts of depictions do not index or reproduce previously experienced music, but rather stand as both a model of and a request for a following production by the student.” (ibid.: 57). Stukenbrock (2014) outlines the embodiment of instructive actions by analyzing how instructors demonstrate “best practices” within instruction sequences. Embodied demonstrations or quotations therefore focus on the “howness” (ibid.: 88) of the instructed action.

On the other side, responsive actions can be embodied as well. Recently, Keevallik (2018) presented different settings where participants respond without using language or using alternatively verbal and embodied actions: in some types of situations, such as during surgery, dance/music lessons or in the cockpit, the instructed action has to (or at least can) be realized manually or bodily.

Additionally, instructions have been analyzed with regard to the temporality of the activity and/or the instructed action (e.g. Mondada 2013, 2014b, 2018) as well as to the mobility of the participants during the instruction sequence (e.g. Broth & Lundström 2013; Keevallik & Broth 2014). Keevallik & Broth (2014: 16) argue that “responsive action can be prepared during the evolving directive, displaying understanding of the general activity structure”, in other words, instruction and instructed action can be accomplished nearly simultaneously.

In videogame interactions as well, instruction sequences have been studied from different points of view, considering mostly their timely unfolding and their embodiment (e.g. Mondada 2011, 2012; Reeves et al. 2015).

However, in our data, certain sequences are different, either because the instructed action is designed as “now directive” (Vine 2009), or because the responsive action is not produced directly after the instruction (without creating any trouble in the ongoing interaction), or because the instructed action has already started before the instruction. We will analyze these sequences as encouragements and, according to the differences we have just pointed out, will distinguish two types of encouragements: re-motivation encouragements (3.1) and encouragements to continue (3.2).

3.1 Re-motivation encouragements

The first type of sequence we will examine shows instructions which are characterized as follows:

· The instructed action cannot be identified precisely. However, this is not treated as problematic in the ongoing interaction.

· The turn design indicates an urging character (for instance by NOW-directives, emphatic prosody etc.), but the responsive action does not follow immediately. And again, this is not treated as problematic.

· The instruction appears in a very specific gaming situation: The addressed player(s) show(s) their disengagement in the ongoing game.

In the following section we will detail this type of sequence more precisely. We are drawing on a single extract which is part of a game session where five participants play, for five hours, different games in different configurations of players. In this excerpt, Celestin (Cel) and Benoit (Ben) are playing Dragon Ball Z (on the Playstation console) against each other, while the other three participants are non-players (Xavier, Rodrigue, Maxime). The excerpt takes place after about 10 minutes of gameplay. Figure 1 shows the two views of the participants as well as the screen which is split down the middle. Each player has his own half of the screen that represents the fight from his avatar’s perspective.

Figure 1

Excerpt 1: “vas-y benoit” (Dragon Ball Z)

01 *(1.3) scrC *8 punches, 8640 points 02 BEN $+je déteste ce gorille I hate that gorilla benG $knits his brows Aben +twists on the opponent’s blows 03 +#(0.6) Aben +jumps and marks time, punches the air -->7 scrC *6 punches, 3170 points 04 ROD *allez vas-Y benoit c'mon go benoit scrC *number of punches rises quickly from 1 to 6 05 XAV +*[fais carré=enfoncé ]fais carré=enfoncé press square press square benG +moves the torso backwards 06 %(0.2) Acel %attacks Aben’s avatar 07 BEN *moi/ me scrC *number of punches rises quickly from 1 to 7 -->11 08 (0.7) 09 XAV +non non (xxx) pour rien no no (xxx) for nothing Aben +attacked and punched by opponent 10 (0.6) 11 XAV **#joli nice scrC *7 punches, 3160 points scrB *square button im #112 (0.6) 13 XAV va à son niveau et fais carré enfoncé go up to him and press square 14 $(0.4) rodG $moves the head and looks towards XAV 15 ROD j` pense qu'il faut aider benoit plutôt I think we should help benoit 16 (0.4) 17 BEN non mais j'ai pas besoin d'aide %moi c'est ce perso de MERde no but I don’t need help it's this damn character Acel %reaches maximum power 18 là: *il est NUL he is a wimp scrC *super explosive wave option 19 XAV *oui::: (xxxx) yes (xxxx) celG *raises left arm 20 ROD il est mort #là\ he is dead here scrR #1180 points 21 (0.4) 22 XAV +(xxxx)/ *#fait juste carré enfoncé (xxxx) just press square Aben +punches scrB *defense, 380 points im #223 *(3.0) scr *Acel knocks out Aben

At the beginning of the game, Cel and Ben choose their avatars. Each avatar has its own properties, fighting techniques, weapons etc. Ben has chosen the Great Ape which is a rather slow fighter[3]. Very quickly, Ben loses points in the fights and starts complaining about the avatar, who, according to him, is not strong enough, not fast enough, and does not have the right skills to attack. Prior to this excerpt he shows over several minutes different indices of disengagement in the game: he complains about the avatar, does not take advantage of occasions to attack the enemy, does not use the skills and weapons of his avatar properly, does not defend himself properly against his enemy’s attacks, and so on. The beginning of the excerpt illustrates some of these indices in detail. In line 2, after an on-screen message appears on the screen concerning the high level of Cel in the game (“8 punches 8640 points”), Ben complains about his avatar with a negative assessment (“I hate that gorilla”), accompanied by eyebrow movements (he knits his brows, line 2). At the same time, his avatar on the screen does not counter-attack, but twists on the opponent’s blows and punches the air (lines 2 and 3). Ben therefore indicates that he is in trouble not only locally, but in a more general way: the avatar is positioned negatively as somebody who is not just “not collaborating with” the player, but, in contrast, making it impossible to win. It is therefore not worth trying further. In line 3, a new informing occurs on Cel’s screen concerning the ongoing attack against the avatar of Ben “6 punches 3170 points”.

Rod answers in line 4 to this display of difficulty. He produces a directive (“c’mon go”) which does not refer to a particular action to accomplish in the game. He answers to the more general display of disengagement and projects a more general action in the sense of “keep on playing, you can do it”. Simultaneously, Xav coaches Cel, telling him how to use the controller. In line 5, Xav produces a directive addressed to Cel[4] (“press square”) which refers to a very specific action to accomplish: press one specific button on the controller. Ben treats this turn as addressed to himself and initiates a self-correction in line 7 (“me”): From his point of view, Xav answers to Ben’s local difficulties in the game and instructs a particular action to accomplish immediately. By pressing the square button, the avatar will fight with his fists (the triangle button makes the avatar fight with his feet).

Even if these two turns are addressed to different players (Ben vs Cel), Ben treats them as potentially addressed to him. Both turns are NOW-directives, but they differ with regard to the environment they refer to, the type of action they project, the temporality of the instructed action and the epistemic stance displayed by the instructor. Xav refers to a local display of difficulties, and Rod to a general display of disengagement. Xav asks for a specific action to accomplish in order to overcome the difficulties, whereas Rod asks to face the choice of the avatar as well as the difficulties in the game and not give up. Xav projects an immediate accomplishment of the instructed action, and Rod projects a more general display of engagement over time. Finally, Xav shows an epistemic access to technical information and positions, whereas Rod does not show any asymmetry in knowledge or access to knowledge.

Let us take a closer look at the way Ben responds to these turns. He does not press the square button in order to accomplish the instructed action; rather, he does not have time because Cel’s avatar attacks Ben’s avatar (line 6) and knocks him out. But in line 7, after having been attacked again by his opponent in the game, he initiates a self-correction by asking to whom the instruction might have been addressed (“me/”). He therefore displays understanding of Xav’s turn as instruction and non-understanding with regard to the addressee of the instruction. In the subsequent turns, Xav does not produce the repair initiated by Ben, but rejects it, thus displaying that his instruction had not been addressed to Ben. Then, he continues coaching Cel.

How does Ben respond to Rod’s turn? Since “go” is a rather vague indication of what to do and the gaming context does not give more precise information, it is difficult to discern whether or not Ben accomplishes what is asked of him. He is not producing a verbal turn in response to Rod, but slightly changing his posture by moving his head backwards. Neither is he producing a particular action in the game, although no particular action has been requested. Nevertheless, nobody addresses this absence of a responsive action. In the following turns, Ben again blames his avatar (lines 17-18), but in spite of the growing strength of Cel’s avatar he nevertheless starts defending himself. When Cel and Xav already claim victory for Cel’s avatar (line 19), Ben does not give up: his avatar stands up, punches his opponent and hereby starts earning points (line 22, im. #2). It is particularly interesting that he thereto uses the square button, as indicated in Xav’s instruction as well as on his screen (line 11, im. #1). Even if Cel’s avatar wins the duel (line 23), by defending himself in a rather hopeless situation, Ben shows traces of re-engagement in the game.

Simultaneously, Xav produces different instructions and assessments which can now be identified as addressed to Cel (lines 11, 13, 19, 22). Rod therefore asks Xav to help Ben who is visibly in greater trouble than Cel (line 15). Ben rejects this request for help in his favor (line 17). With the rejection of help, he clearly rejects (technical or strategical) instructions, but not necessarily an encouragement.

Ben’s answers illustrate the differences between the two actions and action sequences: one is treated as an instruction which has to be accomplished immediately (and if not, it has to be shown why); the other one is treated as an encouragement device which calls not for immediate accomplishment of a specific instructed action but for a general display of engagement. According to these sequence structures, we can distinguish two types.

The instruction sequence can be described as follows:

A: locally shows difficulties in the game

B: imperative as NOW-directive: precise instruction claiming differences in epistemic access and epistemic status

A: instructed action directly after the instruction [or another responsive action related to the instruction]

The encouragement sequence shows the following sequence structure

A: displays disengagement and general difficulties

B: imperative as NOW-directive: opaque instruction not claiming any differences

in epistemic access and epistemic status

A: no specific instructed action can be accomplished, absence of a responsive turn.

Hence, the absence of an instructed action (and a response to the instruction-turn) does not mean that participant A does not respond to B’s turn. He responds to the encouragement by displaying re-engagement. In contrast to the instructed action in the instruction sequence which occurs directly after the instruction-turn, the display of engagement cannot be shown by one single turn or by one single action. It needs to be produced across a certain timespan which covers different turns and different actions in the game. We try to visualize the structure in the figure 2 below.

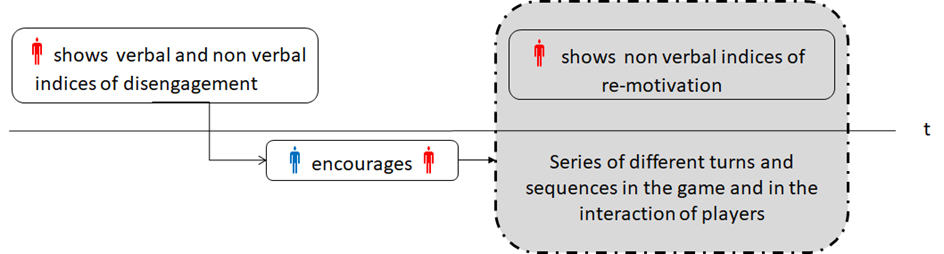

Figure 2

A participant R (red colour) displays a

lower engagement in the game over a certain timespan (first part). At one

point, another participant B (blue colour) is encouraging him (second part).

The projected answer to this type of encouragement is to show (re-)motivation

and to persevere (third part). This

(re-)motivation needs to be shown over time; the following turns should

therefore show fewer or weaker indices of disengagement.

In the excerpt 1 (“vas-y benoit”), Ben does not answer to Rod’s encouragement by a single action in the game, accomplishing a precise action in the game. But he does not stop playing, and after the instruction sequence initiated by Xav directly after the encouragement turn, Ben changes his way of playing, his avatar becomes more feisty, he starts defending himself, and he earns points.

3.2 Encouragement-to-continue

The second type of sequence we will look at is rather frequent in our data and is characterized as follows:

· The instructed action can be identified precisely, but it has already started before the instruction. This is not treated as problematic by the participants.

· The turn design indicates an urging character and is characterized by repetition and rhythmicity.

· The sequence appears in moments of heightened tension in the game: the player is going to win something, progress to a higher level, lose something, or find himself in danger.

We will detail these specificities in the next extract. Excerpt 2 is an example from another setting: Four players are sitting on the sofa, side by side and playing New Super Mario Bros on the Wii console. They are together on the same team and progress together in the game world. Figure 3 shows the avatar that each player controls.

Figure 3

In this excerpt, the avatars of Luc and Dom are dead. Luc’s avatar has no more life points; he will not return immediately to the game. Dom’s avatar, in contrast, still has still life points remaining and is waiting to be able to play again. Both players are thus momentarily non-players of the ongoing actions (but they are still members of the team). At the beginning of the extract, all four participants are sitting on the sofa, gazing at the screen. Lea and Vero hold their controllers with both hands, ready to quickly press the buttons, whereas Luc and Dom hold their controllers with only one hand (im. #3).

Excerpt 2: “la pièce la pièce la pièce” (New Super Mario Bros)

01 DOM #@ouh ça sent l` piège\ vas-y tape %(0.2) tape @

oh this seems like a trap come on hit it (0.2) hit it

Aver @jumps twice on the square to retrieve the coin @

Adom %reappears inside a bubble

im #im.3

02 (0.4)

03 VER [ben oui/ ]

well yes

04 DOM [tape ]

hit it

05 LUC la [pièce/ @la pièce/ la ] @[pièce/ ]

the coin the coin the coin

06 DOM [saute/ et libère la pièce vers le bas/]

jump and free the coin

Aver @jumps once on the square to drop the coin@

07 VER [ben #@@c’est] c` que j`@

well that‘s what I

Aver @jumps once @

ver @looks at her

controller-->09

im #im.4

02 (0.4)

03 VER [ben oui/ ]

well yes

04 DOM [tape ]

hit it

05 LUC la [pièce/ @la pièce/ la ] @[pièce/ ]

the coin the coin the coin

06 DOM [saute/ et libère la pièce vers le bas/]

jump and free the coin

Aver @jumps once on the square to drop the coin@

07 VER [ben #@@c’est] c` que j`@

well that‘s what I

Aver @jumps once @

ver @looks at her

controller-->09

im #im.4

08 @fait/ @

did

Aver @does a spin@

09 LEA @doudou t` es rev`nu dans l` jeu hein\@

doudou you respawned eh

Aver @falls on the square and wins the coin

ver -->@

10 (0.4)

08 @fait/ @

did

Aver @does a spin@

09 LEA @doudou t` es rev`nu dans l` jeu hein\@

doudou you respawned eh

Aver @falls on the square and wins the coin

ver -->@

10 (0.4)

In this excerpt, Vero tries to collect a coin: her avatar jumps twice on the brick to retrieve the coin (line 1). While Vero‘s avatar jumps on the brick, Dom offers an evaluation of the situation (“this seems like a trap”) and an instruction (“come on hit it”) addressed to Vero and her avatar. The turn starts simultaneously with Vero‘s action and focuses on the way to deal with the brick: “hit it”. This is exactly what Vero‘s avatar is doing. Vero therefore answers in line 3 by acknowledging Dom’s turn and aligning to the action he suggests accomplishing. Her avatar continues jumping on the brick (line 6).

In lines 5 and 6 Luc and Dom refer again to the action of Vero‘s avatar. Both produce instructive actions: Luc focuses on the object she is trying to win (“the coin the coin the coin”, line 5) and Dom on the actions she has to accomplish (“jump and free the coin”, line 6). It is interesting that those two turns are produced at a moment when Vero‘s avatar has already jumped twice on the brick and is preparing for a third jump. In other words, Vero’s avatar has already been accomplishing the action of jumping for a while.

Luc’s turn in line 5 specifies the object which must be found. He does not directly indicate an action that has to be accomplished and takes into account the fact that Vero’s avatar is already jumping on the brick. The turn rather focuses on something that Luc knows thanks to previous, nearly identical situations in the game. The turn is characterized by a clear rhythmicity and a triple repetition.

Self-repetition with regard to similar types of turns has already been studied in conversation analysis. Keevallik (2010b) describes “syntactic reduplication” and shows that “reduplicated imperatives urge the prior speaker to do something he/she just talked about” (2010b: 821). De Stefani & Gazin (2014), who analyze Italian driving lessons, show that by formulating short turns, the instructor “displays that the complying action has to be accomplished in a narrow time frame” (ibid.: 68). And the combination of minimal units and their (multiple) repetitions “allow INS [the instructor] to exhibit and STU [the student] to recognize that the action has to be executed urgently.” (ibid.) Reynolds (2017b) analyzes incitement sequences in US powerlifting training sessions. He finds roughly the same type of turns which he relates to Keevallik’s (2010b) description of “syntactic reduplication” but with three or more items. Baldauf-Quilliatre (2014b) studies encouragements which are based on instructive or evaluative turns and shows that the encouragement-turns are generally composed of one single lexical unit which is repeated several times. The repeated elements are produced in immediate succession by one speaker in a single intonation contour and form one TCU. In all of these analyses, the display of urgency seems to be the most important function of the repetitions. This is also the case in excerpt 2: the triple repetition of “the coin” urges the co-participant to accomplish the indirectly instructed action (retrieve the coin).

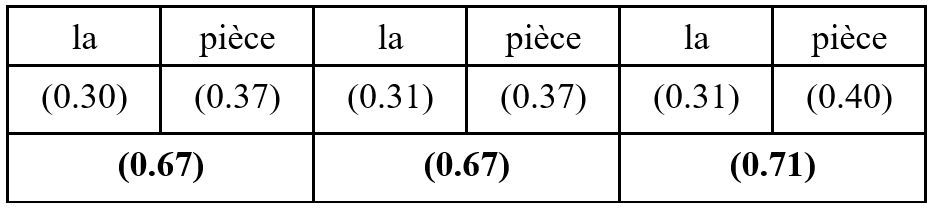

Another important aspect in this turn is its rhythmicity. The repeated lexical items can be produced as “multiple sayings” (Stivers 2004), that is, under a single intonation contour, or as different units, grouped through rhythmicity. In this excerpt, the turn in line 5 is composed of the nominal phrase “la pièce” (determiner + noun), repeated twice. Each noun phrase has its own pitch movement and therefore represents its own intonation unit. It starts with a high onset on the determiner and ends with a larger downstep on the noun. The pitch movement is the same for all three units but the pitch level is lower on the second and third ones.

Besides the pitch movement, rhythmicity is also visible in terms of duration and accent: Luc’s turn is characterized by a “markedly high density of accentuated syllables” and a “rhythmic organization with markedly short isochronous cadences” according to Selting’s (1994: 404) constitutive cues for emphatic speech style. Skutella et al. (2014: 5) show that for “motivation-turns” in indoor cycling, accents “occur in immediate precedence” and “sometimes [...] on conjunctions and particles”. In Luc’s turn, each lexical item has a prominent accent, even the determiner “la”. However, in contrast to the findings of Skutella et al. (2014), it is not new information that is marked; the accents are used to structure the turn and to create rhythmic beats. The following lines show a transcription of the rhythm and the pitch accents of Luc’s turn.

/ ↑↑`lA / (0.30)

/ ↓↓´`PIEce / (0.37)

(..)

/ ↑↑`lA / (0.31)

/ ↓↓´`PIEce / (0.37)

(..)

/ ↑↑`lA / (0.31)

/ ↓↓´`PIEce / (0.40)

speech rate: 0.39 words per second

The three lexically identical units (“la pièce”) last 0.67 seconds for the first two and slightly longer (0.71 seconds) for the third one. When looking at the two lexical items in each unit (the determiner “la” and the noun “pièce”), each determiner and each noun has the same length — 0.30 to 0.31 seconds for the determiner, and 0.37 to 0.40 seconds for the noun.

Table 1

Dom’s instruction in line 6 is different. By using NOW-directives which indicate a specific action to be accomplished by the avatar in the game (“jump”, “drop the coin”), he signals precisely what the player Vero and her avatar have to do (task-setting request, Deppermann 2015; 2018b). The turn clearly brings in an epistemic stance (Heritage 2012): Dom positions himself as somebody who possesses specific knowledge (concerning the most suitable action of Vero’s avatar at this moment) and as having the right to possess and to express this knowledge. He thereby suggests that Vero is not performing the “right action” (or not performing it properly) at this moment and positions her as the one who needs to be instructed. At the same time, he acts as the one who knows and who has the right to convey information (in form of an instruction) and who does not.

Where Dom displays expertise, Luc shows support. His turn is not based on a difference in expertise concerning the avatar’s actions. Moreover, he indicates that he has understood what Vero is doing — she is already accomplishing the right action and therefore does not need somebody else to tell her what to do. He therefore positions himself as Vero’s “equal” and as a participant who is engaged in what she is doing.

In contrast to excerpt 1, both turns respond to the same action in the game: the avatar jumping on the brick. But they show some differences concerning the turn design and the epistemic stance they display. Let us now have a look at Vero’s answering turn in order to understand the action it projects.

First, we observe her avatar jumping on the brick for a third time during the second item of Luc’s “the coin” and right after the beginning of Dom’s turn. Vero then explicitly rejects Dom’s instruction as a kind of assistance that she does not need (“well that’s what I do”, lines 7-8). She thereby challenges his epistemic stance and his positioning of her as somebody who needs instruction. At the same time, she looks at her controller (im #4) and her avatar jumps on the brick for a fourth time. Looking at the controller at this very moment seems to be a notable action. On the one hand, looking away from the screen implies that the screen does not need all the attention: Vero’s avatar is not moving, he repeats an action several times and jumps on the spot — he (and the gaming environment) therefore does not need to be supervised and constantly controlled. On the other hand, directing his gaze to the controller implies that the controller is the element that now needs supervision. Vero’s avatar is already jumping, but she has not yet acquired the coin. To do so, she has to press two buttons simultaneously (button 2 + D-pad down). The avatar then spins around and the coin drops. But until this moment, Vero’s avatar does not spin, he just jumps and moves forwards which means that she pressed the right buttons, just not simultaneously. Looking at the controller might be a way to ensure that she really presses the two buttons at the same time. It could then be considered as responding action with regard to the instructive turn of Luc and the action requested by Dom (“drop the coin”). By focusing only on the object, Luc confirms the action of Vero’s avatar (jumping on the brick). Vero now confirms Luc’s turn by continuing the confirmed “right action” and by indicating with a change of gaze that she is trying to find a way to double her effort (by pressing the two buttons simultaneously). Once the avatar has jumped for the fourth time, he completes the spin and the coin drops out (line 9); the sequence is now closed.

Dom’s and Luc’s turns both occur at a moment when the instructed action is already going on. They differ considerably in the turn design, thereby displaying different stances. Furthermore, they do not project the same action. Whereas Dom’s turn projects an action which is presented as differing from what Vero’s avatar is doing (corrective instruction), Luc’s turn projects a continuation. Vero’s responsive actions give evidence for these differences: she rejects Dom’s instruction by arguing that she is already doing what he has instructed her to do (namely, jumping) and she confirms Luc’s turn by continuing her ongoing actions and by displaying an effort to increase her avatar’s performance (by looking at the controller, she shows that she intensifies her effort of pressing the buttons simultaneously). Both turns do not project the same type of answer and are not responded to in the same way. While Dom produces an instruction which is treated as such (rejection as irrelevant, not useful), Luc produces an encouragement which projects a “display of effort” (Reynolds 2017a). This “effort” is accountable: the co-participant must show that he continues accomplishing the action he has started and that he is doing everything in his power to increase his chances of success. As Reynolds (2017a) states, the co-participant has a moral obligation to display effort. In excerpt 2, Vero displays effort by making her avatar jump a third and a fourth time on the brick and by directing her gaze to the controller in order to assure a better coordination of her controller inputs (pressing the buttons simultaneously).

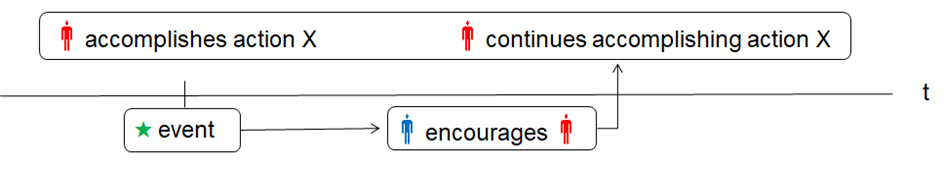

As in the first excerpt, Luc’s turn is treated as an encouragement device which does not ask for immediate accomplishment of the instructed action. But in contrast to excerpt 1, the turn does not occur after a display of disengagement and does not project a display of re-engagement. We consider it as encouragement to continue which asks for displays of effort. The sequence structure is visualized in the figure 4 below.

Figure 4

A participant R (red colour) is accomplishing an extra-linguistic action in the game. At some point, generally when the participant R has either nearly accomplished the action or, on the contrary, is going to fail, a co-participant B (blue colour) produces an encouragement turn. The turn has the form of an instruction, but does not primarily account for the instructed action (which is already going on). The participant R responds to this encouragement by continuing to accomplish the action and by displaying effort in doing so. He has the moral obligation, lest he be considered a “bad player”.

Two other features occur in our data which merit our attention for the description of the action: First, the turns used to encourage a co-participant are generally “corrective” and therefore take into account the fact that the action is already going on. Second, it is possible that these turns are addressed to one’s own avatar. The player positions himself as a spectator of his avatar’s actions and the avatar as a participant who can respond/react and who holds responsibility (para-interaction, see Baldauf-Quilliatre & Colón de Carvajal 2015 and 2019). Research on para-interaction has shown that participants can consider somebody locally as a co-participant even if they know that he/she will not be able to respond (this has been shown for instance for the para-interaction of television viewers with characters or personae on the screen; Holly & Baldauf 2001). But it seems curious to address a corrective instruction to such types of “co-participants” who, in fact, are unable to correct their own actions.

4. Discussion: Instruction? Incitement? Encouragement?

In the previous section we have shown two particular types of instruction sequences and we have analyzed them as encouragements. In this section we will argue more generally for a difference between instructions and encouragements in videogame interactions.

Our argumentation is based on different claims that we detail below:

(1) They occur in particular situations in the game and in the gaming interaction.

(2) They “instruct” an unspecified action (3.1) or an action which is already going on (3.2).

(3) They show a very specific turn design (3.2).

(4) They display different epistemic stances.

(5) They do not primarily project the accomplishment of the instructed action, but a display of effort — to re-engage in the game (3.1) or to continue the ongoing action (3.2).

First, the previously analyzed sequences occur in two particular situations and answer to specific displays. Mondada (2011), who studied directives in videogame interactions, shows the importance of timing by analyzing the moment-by-moment unfolding of the sequence, “orienting to the temporality of the current action and of the mobile context” on the one hand and to the directive’s “emergent format being reflexively adapted to the evolving circumstances” on the other (ibid.: 35). Yet her analyses do not specify a particular moment for the initiation of instructive actions; she only draws on their placement with regard to the current action and to the configurations within the game. This is different for our examples. The “re-motivation encouragement” responds to a general display of disengagement in the game, the encouragement-to-continue occurs in a particular “dangerous situation” for the encouraged player and draws on this danger. As the excerpts have shown, this does not mean that instruction sequences cannot occur in similar situations. But in the case of general disengagement, an instruction responds to the local display of a specific problem, not to the general disengagement. In “dangerous situations,” instruction sequences can occur in the same way that encouragement sequences do. But instruction sequences can also occur elsewhere, whereas encouragement sequences do not.

Second, different studies have drawn on the embodiment of instructions and on the finely tuned coordination between instruction and instructed action (e.g. the different papers in Sorjonen/Raevaara/Couper-Kuhlen 2017). We therefore argue that we should look carefully when we have doubts concerning the coordination in instruction sequences as well as the “instructiveness” of the action. Directives responding to a general display of disengagement are very vague and “non-instructive”; they generally occur, as in excerpt 1, after specific local problems, but they do not allow for the resolution of these problems. Encouragements to continue, in contrast, are very specific, but in this case the instructed action is already going on. Two explanations could be considered in this case. A) They could be a particular kind of instruction sequence where the instruction starts nearly simultaneously with the responsive action, as described for instance by Broth & Keevallik (2014) and Keevallik (2018) for dance classes or Pilates lessons. Keevallik (2018: 9) shows for Pilates lessons that the instructed action occurs directly after the turn initial particle produced by the teacher; “the descriptive ‘upward” emerges partly as a responsive approval of their bodily action.” But a fine-grained analysis shows that the “responses” in our data start before the “instruction” which is different and questions the instructiveness of the action. B) They could be “corrective instructions” and as such occur during an ongoing action in order to correct it. Corrective instructions “are dealing with how to perform the task” (Deppermann 2015: 74). To some extent, encouragements are corrections: “They explicitly formulate individual steps of the larger sequence […], and they immediately respond to the emerging local contingencies of the student's actions […]” (ibid.). But they are not based on improvement; they do not indicate that the co-participant has to improve his action. To the contrary, they validate the co-participant’s action, encourage him to continue and show their support.

Third, in both types of sequences, the “instructive” turn shows a particular turn design, especially in the encouragement-to-continue. Drew (2013) has highlighted the interconnection between the way a turn is designed and the prior turns to which it is related, between the design of a turn and what the turn is doing (the action it accomplishes), as well as between turn design and its (intended) recipients (recipient design). Stivers & Rossano (2010) argued for a new consideration of turn design with respect to the features that mobilize responses. Based on these analyses we will argue that the particular turn design has to be taken into account for the description of the action. It is less spectacular in the re-motivation encouragement: in our data, the turn is always composed of a directive in the semantic field of “go” which does not always take into account the recipient (the plural form “allez” is sometimes used even for one single recipient) and an address term, but there are only a few examples and we can easily imagine that there are other possibilities to form these turns. In contrast, encouragements-to-continue turns present a very specific design: they are characterized by multiple repetitions of short (generally mono- or disyllabic) lexical items which are either produced under one single intonation contour as one intonation unit (as described by Stivers 2004 for “multiple sayings”) or which are grouped through rhythmicity. In the latter case, rhythmicity appears because of similar pitch movements in the grouped items, a nearly equal duration of each, and numerous similar types of accents. Rhythmicity in instructive actions has already been described as a device for “establishing the necessary rhythm” for the instructed action (Broth & Keevallik 2014: 12). Similar functions have been described for indoor cycling, with a special regard to prosody (Skutella et al. 2014). But this is not the case in our examples. In excerpt 2 (as in all the other occurrences in our data), for instance, the rhythmicity of the turn is not related to the “instructed” action. We therefore argue that the rhythmicity (as well as the repetition) participate in the construction of the sequence as cheering and as not instructive.

Fourth, in contrast to instruction sequences, encouragement sequences do not display differences in epistemic status. Mondada (2014b) shows very thoroughly for cooking courses that “the instructions’ progressivity and format […] are shaped by the orientation toward the knowledge attributed to the recipients – their epistemic status (Heritage 2012)” (ibid.: 207-208). In contrast to teachers, trainers and other instructors who can rely on an institutional claim of knowledge, there is a priori no such claim in videogame interactions[5]. Participants therefore have to construct asymmetry without any institutionalized claim, only by showing their expertise and thereby displaying that the co-participant(s) do not have the same. Mondada (2011) has analyzed how directives are used in a football video game. She argued that directives “can locally highlight asymmetries, impositions, authority and the right to evaluate and dictate the other’s conduct” and that these relationships “are implemented by the way in which directives are locally produced, particularly formatted, finely responded to and assessed by the participants in specific contextual configurations.” (ibid.: 47). Drawing on these findings, we can assume that directives and more generally instructions locally claim epistemic authority and knowledge and attribute different epistemic statuses (lesser knowledge) to the co-player. They are formally responded to either by an acceptance or a rejection of these epistemic stances. However, the “instructive actions” in which we are interested do not claim differences in epistemic status. They display symmetric knowledge, align to the action in the game chosen by the co-player and confirm its “efficiency”. For this reason, the epistemic stance they display is never rejected or questioned in our data (and neither is the action itself).

Fifth, encouragements do not primarily

project the accomplishment of the “instructed” action. Reynolds (2017a), who

analyzes incitement sequences among powerlifters, states that incitement “is an

action of encouraging lifters during a lift. Further, incitement proposes an

increase in the intensity of action on the part of the incited party. That is,

that if someone is inciting you with ‘go go go’ or similar a lifter should increase

the intensity of their lift.” (ibid.: 111). The projected action, then, is

“effort”. This seems to be similar in our data even if the notion of “effort”

has to be adapted: addressees of encouragements in videogame interactions

display other types of effort than powerlifters. The addressee of a

re-motivation encouragement has to show that he is re-engaging in the game. Not

only does he have to locally accomplish an instructed action, but he also needs

to display engagement within a certain timespan. The addressee of an

encouragement-to-continue must pursue his ongoing action in the game and show

that he is honestly trying to accomplish it, independently of the actual

effectiveness of the action in the game. Encouragements as we understand them

are rather similar to incitements. They project effort and are used in a

certain sense to “cohort the team” (Reynolds 2017a). But videogame players form

a different kind of “team” than powerlifters. They act together in the

game — every player’s action has consequences for the co-players.

Additionally, games generally go on, even if the players do not move. As in

other multi-activity settings (e.g. Haddington, Keisanen & Mondada 2014),

the different activities may have different temporalities. In other words, at

least certain types of actions (assessments, encouragements) do not suspend the

progression of the non-linguistic activity. For videogames, Mondada (2012) has

shown that “in the game”, players comment on-screen actions/events or instruct

co-players, while more complex sequences like negotiations of responsibility or

discussions of strategies are placed “outside the game”. Encouragement are part

of these “in-the-game-on-screen-comments” in that similar to powerlifters, nobody

suspends their current activity in order to engage in the encouraged ongoing

action. Furthermore, videogame “teams” are unaware of institutionalized roles such

as coaches or seniors, and with their encouragements, the participants do not assume

the role of experts. To the contrary, as mentioned in the previous paragraph,

encouragements are rather used as displays of symmetry of knowledge. For these

reasons we prefer to use the term “encouragement” instead of “incitement” to

describe these action sequences.

Our discussion aims to outline some particularities of encouragements and therefore to argue in favour of considering them as a proper type of action. In so doing, we have focused on one special kind of encouragement: directives as “in-the-game-on-screen-comments”. This might provide a reductionist vision of encouragements. We are aware of the fact that encouragements do not always look like instructions; they are produced in very different ways according to the different types of sequences and situations in which they occur. Our paper and argumentation make no pretense of covering all of these sequences and situations, but show some of the particularities of encouragements for a very specific type of interaction and a very specific sequence. This section therefore focuses only on the opposition between encouragements and instructions and does not take into account the whole array of encouragement sequences.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we have argued for considering encouragements as a type of action, by focusing particularly on the differentiation between instruction and encouragement sequences. We have showed that even if they seem to be similar prima facie, they are in fact characterized by several important differences: differences concerning the previous actions to which they are connected and the actions they project, differences concerning the epistemic stance displayed in the encouragement or instruction turn, and differences concerning the turn design. These differences should not been neglected.

In our data we observed two different types of encouragement sequences which we called “re-motivation encouragement” and “encouragement-to-continue”. Re-motivation encouragements respond to a display of disengagement in the game and project a display of re-engagement therein. The answer they propose is not a single action, but a display of engagement over time through different actions (in the game and/or in the players’ interaction). Encouragement-to-continue turns respond to a challenging situation in the game. They validate an ongoing action of the co-player as “good” and show support. The co-player has to respond by pursuing this action and by increasing effort. Encouragement-to-continue turns are characterized by a particular turn design including multiple repetitions of lexical items and rhythmicity. In both types of encouragements, the turns do not display asymmetries in knowledge and do not attribute different kinds of expertise to the participant who encourages and to the co-participant who is encouraged.

Although the focus of our paper was clearly centered on the description of encouragements in contrast to instructions in videogame interactions, we are aware that this binary categorization does not take into account the complexity of the closely related actions. It is therefore not only necessary to investigate more “complex cases” in order to describe the ambiguity between related actions in this data, but it also seems relevant to extend our analysis of instructions and encouragements to other types of sequences related to simultaneous on- or off-screen events. A comparison of sequence organization and of the multimodal turn design needs to be accomplished in order to understand and explain the complexity of this “family of actions”.

6. Conventions of transcription

6.1. ICOR Convention used in excerpts 1 and 2

http://icar.univ-lyon2.fr/projets/corinte/bandeau_droit/convention_icor.htm

Text in bold translation

Text in grey information concerning events on the screen,avatars’ or players’ actions

[ ] Overlapping talk

/ \ Rising or falling intonation

° ° Lower voice

::: Lengthening of the sound or the syllable

p`tit Elision

trouv- Truncation

xxx Incomprehensible syllable

= Latching

( ) Uncertain transcription

(( )) Comments

& Turn of the same speaker interrupted by an overlap

(.) Micro-pause

(0.6) Timed pause

6.2. Multimodal convention (Mondada 2018)

$ $ Gestures and descriptions of embodied actions are delimited between

two identical symbols (one symbol per participant) and are

§ § synchronized with corresponding stretches of talk

£ £

* screen events, is indicated with a specific symbol showing its

position within the turn at talk

# image (screenshot), is indicated with a specific symbol showing its position within the turn at talk

--> The describes action continues across subsequent lines

-->> The described action continues after the excerpt’s end

6.3. GAT 2 convention used for the rhythmic transcription (Couper-Kuhlen/Barth-Weingarten 2011)

↑` small pitch upstep to the peak of the accented syllable

↑↑` high pitch jump to the peak of the accented syllable

↓↓´` low pitch jump combined with a rising falling accent

↑↑`´ high pitch jump combined with a falling rising accent

´`COURS rising falling accent of the accented syllable

Acknowledgments

We are deeply indebted to Kristian Mortensen, Edward Reynolds and an anonymous reviewer for their comments to a previous version of the paper.

We are also grateful to the Labex Aslan (ANR-10-LABX-0081) of Université de Lyon, for its financial support within the program ‘‘Investissements d’Avenir’’ _(ANR-11-IDEX-0007) of the French government operated by the National Research Agency (ANR).

7. References

Arminen, I., Licoppe, C. & Spagnolli, A. (2016). Respecifying mediated interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction 49, 290-309.

Baldauf-Quilliatre, H. (2014a). Formate knapper Bewertungen beim Fußball-Spielen an der Playstation. In C. Schwarze, C. Konzett (Eds.). Interaktionsforschung: Gesprächsanalytische Fallstudien und Forschungspraxis (pp.107-130). Berlin: Frank & Timme.

Baldauf-Quilliatre, H. (2014b). Multiple Sayings: répétition et encouragement. Semen - Revue de sémio-linguistique des textes et discours 38, 115–135.

Baldauf-Quilliatre, H. & Colón de Carvajal, I. (2015). Is the avatar considered as a participant by the players? A conversational analysis of multi-player videogame interactions. PsychNology Journal 13(2-3), 127-148.

Baldauf-Quilliatre, H. & Colón de Carvajal, I. (2019). Interaktionen bei Videospiel-Sessions: Interagieren in einem hybriden Raum. In K. Marx, A. Schmidt (Eds.). Interaktion und Medien. Interaktionsanalytische Zugänge zu medienvermittelter Kommunikation (pp. 219-254). Heidelberg: Winter.

Brink, G. (2001). Zieht den Bayern die Lederhosen aus …“ Fußball-Fangesänge – Ein Thema für den schulischen Musikunterricht? Musik und Unterricht, 44–51.

Broth, M. & Lundström, F. (2013). A Walk on the pier. Establishing relevant places in a guided, introductory walk. In P. Haddington, L. Mondada, M. Nevile (Eds.). Interaction and mobility (pp. 91-122). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Brunner, G. (2009). Fangesänge im Fußballstadion. In A. Burkhardt, P. Schlobinski (Eds.). Flickflack, Foul und Tsukahara. Der Sport und seine Sprache (pp. 194-210). Mannheim: Dudenverlag (Thema Deutsch, Band 10).

Burkhardt, A. (2009). Der zwölfte Mann - Fankommunikation im Fußballstadion. In A. Burkhardt, P. Schlobinski (Eds.). Flickflack, Foul und Tsukahara. Der Sport und seine Sprache (pp.175-193). Mannheim: Dudenverlag (Thema Deutsch, Band 10).

Colón de Carvajal, I. (2011). Les énoncés choraux: une forme de segments répétés émergeant dans les interactions de jeux video. In H. Ter Minassian (Ed.). Les jeux vidéo comme objet de recherche. Collection Lecture > Play. (pp. 149-166). Paris : Questions théoriques.

Couper-Kuhlen, E. & Barth-Weingarten, D. (2011). A system for transcribing talk-in-interaction: GAT 2. Gesprächsforschung–Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 12, 1–51.

Couper-Kuhlen, E. & Selting, M. (2017). Interactional Linguistics: An Introduction to Language in Social Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Couper-Kuhlen, E. & Selting, M. (2001). Introducing interactional linguistics. In M. Selting, E. Couper-Kuhlen (Eds.). Studies in interactional linguistics. (pp. 1-22). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

De Stefani, E. & Gazin, A.-D. (2014). Instructional sequences in driving lessons: Mobile participants and the temporal and sequential organization of actions. Journal of Pragmatics 65, 63-79. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2013.08.020

Deppermann, A. (2015). When recipient design fails: Egocentric turn-design of instructions in driving school lessons leading to breakdowns of intersubjectivity. Gesprächsforschung–Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 16, 63-101.

Deppermann, A. (Ed.). (2018a). Instructions in driving lessons. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, special issue, 28(2).

Deppermann, A. (2018b). Instruction practices in German driving lessons: Differential uses of declaratives and imperatives. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 28(2), 265-282.

Drew, P. (2013). Turn Design. In J. Sidnell, T. Stivers (Eds.). The Handbook of Conversation Analysis (pp. 131-149). Malden, Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

Goodwin, C. (2003). The Body in Action. In J. Coupland, R. Gwyn, R. (Eds.). Discourse, the body, and Identity (pp. 19-42). New York: Palgrave MacMillian.

Groupe ICOR (2006, August 18). La démarche ethnographique. Retrieved from http://icar.univ-lyon2.fr/projets/corinte/recueil/demarche_ethnographique.htm.

Haddington, P., Keisanen, T., Mondada, L. & Nevile, M. (Eds.) (2014). Multiactivity in social interaction. Beyond multitasking. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Heinemann, T. & Möller, R.L. (2016). The virtual accomplishment of knitting: How novice knitters follow instructions when using a video tutorial. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 8, 25-47.

Heritage, J. (2012). Epistemics in Action: Action Formation and Territories of Knowledge. Research on Language & Social Interaction 45, 1-29. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.646684

Holly, W. & Baldauf, H. (2001). Grundlagen des fernsehbegleitenden Sprechens. In W. Holly, U. Püschel, J.R. Bergmann (Eds.). Der sprechende Zuschauer. Wie wir uns Fernsehen kommunikativ aneignen (pp. 41-60). Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Jakonen, T. (2018). Professional Embodiment: Walking, Re-engagement of Desk Interactions, and Provision of Instruction during Classroom Rounds. Applied Linguistics, amy034. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amy034

Keevallik, L. (2018). What Does Embodied Interaction Tell Us About Grammar? Research on Language and Social Interaction 51, 1-21.

Keevallik, L. (2017). Negotiating deontic rights in second position: Young adult daughters’ imperatively formatted responses to mothers’ offers in Estonian. In M.-L. Sorjonen, L. Raevaara, E. Couper-Kuhlen, E. (Eds.). Imperative Turns at Talk (pp.271-295). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Keevallik, L. (2010a). Bodily quoting in dance correction. Research on Language and Social Interaction 43, 401-426.

Keevallik, L. (2010b). Social action of syntactic reduplication. Journal of Pragmatics 42, 800-824. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.08.006

Keevallik, L. & Broth, M. (2014). Getting ready to move as a couple: Accomplishing Mobile Formations in a Dance Class, Space and Culture 17(2), 107-121.

Khodadadi, F. & Gründel, A. (2006). Sprache und Fußball- Fangesänge 30. Retrieved from http://www.linse.uni-due.de/linse/esel/pdf/Fussball_und_Sprache.pdf

Macbeth, D. (2004). The relevance of repair for classroom correction. Language in Society 33(5), 703-736.

Mehan, H. (1979). Learning Lessons: Social Organization in the Classroom. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple Temporalities of Language and Body in Interaction: Challenges for Transcribing Multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction 51(1), 85-106.

Mondada, L. (2017). Precision timing and timed embeddedness of imperatives in embodied courses of actions: Examples from French. In: M.-L. Sorjonen, L. Raevaara, E. Couper-Kuhlen, E. (Eds.). Imperative Turns at Talk (pp. 76-101). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Mondada, L. (2014a). Instructions in the operating room: How the surgeon directs their assistant’s hands. Discourse Studies 16, 131–161. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445613515325

Mondada, L. (2014b). Cooking instructions and the shaping of things in the kitchen. In M. Nevile, P. Haddington, T. Heinemann, M. Rauniomaa (Eds.). Interacting with objects: Language, materiality, and social activity (pp. 199-226), Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Mondada, L. (2013). Coordinating mobile action in real time: the timely organization of directives in video games. In P. Haddington, L. Mondada, M. Nevile (Eds.). Interaction and Mobility (pp. 300-341). Berlin, New York: de Gruyter.

Mondada, L. (2012). Coordinating action and talk-in-interaction in and out of video games. In R. Ayass, R., C. Gerhardt (Eds.). The appropriation of media in everyday life (pp. 231-270). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Mondada, L. (2011). The Situated Organisation of Directives in French: Imperatives and Action Coordination in Video Games. Nottingham French Studies 50, 19-50. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3366/nfs.2011-2.002

Okada, M. (2018). Imperative Actions in Boxing Sparring Sessions. Research on Language and Social Interaction 51, 67-84.

Rauniomaa, M. (2017). Assigning roles and responsibilities: Finnish imperatively formatted directive actions in a mobile instructional setting. In: M.-L. Sorjonen, L. Raevaara, E. Couper-Kuhlen, E. (Eds.). Imperative Turns at Talk (pp. 325-355). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Reeves, S., Greiffenhagen, C., Flintham, M., Benford, S., Adams, M., Row Farr, J. & Tandavantij, N. (2015). I’D Hide You: Performing Live Broadcasting in Public. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’15. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 2573-2582. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702257

Reeves, S., Greiffenhagen, C. & Laurier, E. (2017). Video Gaming as Practical Accomplishment: Ethnomethodology, Conversation Analysis, and Play. Topics in Cognitive Science 9, 308-342. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12234

Reynolds, E. (2017a). Description of membership and enacting membership: Seeing-a-lift, being a team. Journal of Pragmatics 118, 99–119. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2017.05.008

Reynolds, E. (2017b). Incitement in the gym: Using intonation as a resource. Ms.

Schilling, M. (2001). Reden und Spielen. Die Kommunikation zwischen Trainer und Spielern im gehobenen Amateurfußball. Stauffenburg: Tübingen.

Selting, M. (1994). Emphatic speech style: with special focus on the prosodic signalling of heightened emotive involvement in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics 22, 375-408. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(94)90116-3

Sidnell, J. & Stivers, T. (Eds.) (2012). The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Malden, Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

Simone, M. (2018). A situated analysis of instructions in paraclimbing training with visually impaired athletes. SHS Web of Conferences, 52. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20185203001

Skutella, L.V., Süssenbach, L., Pitsch, K. & Wagner, P. (2014). The prosody of motivation. First results from an indoor cycling scenario. In R. Hoffmann (Ed.). Elektronische Sprachsignalverarbeitung (pp. 209-215). Dresden: TUD Press.

Sorjonen, M.-L., Raevaara, L. & Couper-Kuhlen, E. (Eds.) (2017). Imperative Turns at Talk, Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Stevanovic, M. & Kuusisto, A. (2018). Teacher Directives in Music Instruction: Activity Context, Student Cooperation, and Institutional Priority. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. Retrieved fromC:\Users\Isabel\AppData\Local\Temp\ https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2018.1476405

Stivers, T. (2004). “No no no” and Other Types of Multiple Sayings in Social Interaction. Human Communication Research 30, 260-293. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2004.tb00733.x

Stivers, T. & Rossano, F. (2010). Mobilizing Response. Research on Language and Social Interaction 43, 3-31.

Stukenbrock, A. (2014). Take the words out of my mouth: Verbal instructions as embodied practices. Journal of Pragmatics 65, 80-102.

Svensson, M., Heath, C. & Luff, P. (2009). Embedding instruction in practice: contingency and collaboration during surgical training. Sociology of Health and Illness 31(6), 889-906.

Svensson, M. Heath, C. & Luff, P. (2007). Instrumental action: the timely exchange of implements during surgical operations. in: ECSCW 2007 (pp. 41-60), London: Springer.

Tolins, J. (2013). Assessment and Direction Through Nonlexical Vocalizations in Music Instruction. Research on Language and Social Interaction 46, 47-64.

Vine, B. (2009). Directives at work: Exploring the contextual complexity of workplace directives. Journal of Pragmatics 41, 1395-1405. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.03.001

Zemel, A. & Koschmann, T. (2011). Pursuing a question: Reinitiating IRE sequences as a method of instruction. Journal of Pragmatics 43, 475-488.