Social

Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality.

Social

Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality.

2018 Vol. 1, Issue 2

ISBN: 2446-3620

DOI: 10.7146/si.v1i2.110039

Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Why Multimodality? Why Co-Operative Action?

Charles Goodwin

University of California, Los Angeles

Transcribed by Johanne S. Philipsen

This paper is based on a keynote presentation by Charles Goodwin at the 3rd Multimodality Day conference in Copenhagen, Oct 2017. He started the talk in the following way: “Just one thing I want to say before I begin: it is an honor and a pleasure to have spent my life in this field and this community. Doing work that is not trying to make machines of war but to try to find out what it is to be human. And the other side is that I feel very strongly that one of the best things about our lives is that we are in the midst of these intergenerational transmission processes. And one of the great things for me has been all the students and all the colleagues I have had, and the opportunity to share these things.”

1. Multimodality and Human Sociality

What I want to talk about today is: why multimodality? It is a term I do not use all that much because at times the way people talk about multimodality makes it seem as a side thing, and focusing on the language or the action as the core phenomena. However, what I want to argue is that the way human action is built is by bringing different kinds of meaning-making resources together. In fact the only way we can really understand the uniqueness of language is by embedding it within this larger ecology of historically-sedimented meaning-making resources. In terms of alternative approaches, there is a lot of work in for example CA that basically looks at formal action types. As Labov said a long time ago:

“Sequencing rules do not appear to be related to words, sentences, and other linguistic forms, but rather form the connections between abstract actions such as requests, compliments, challenges, and defenses” (Labov & Fanshel 1977:25)

With this approach, however, you move from the details of what is actually in talk, to the form of action types. It is a bit like Gulliver's Travels, where you have people down below actually acting in the world, and then another level on top consisting of these formal types. But what I want to argue is that the structure is actually in the details of what is being done. And also the question of how you go to types is in fact an interesting question - though not just action types, but the kind of types that animate our discourse and our science.

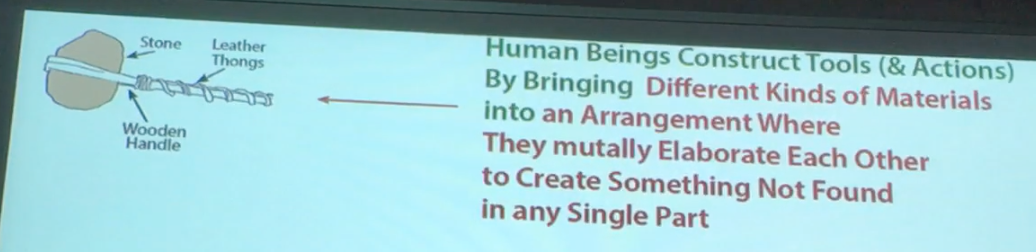

The central argument is that human beings construct both tools and actions by bringing together different kinds of materials into arrangements where they mutually elaborate each other to construct something that is not found in any single part. A simple example: this is an old stone axe from Chile.

Figure 1

It consists of a stone, a wooden handle and thongs that are tying it together. If you disassemble it you cannot find “the axe” in any one of those pieces. It is only when it is brought into this larger arrangement that each of these pieces can properly function in this way. The same is true for language and how it is embedded within a multimodal semiotic ecology.

Some of my earliest work was showing how a sentence is constructed through the simultaneous work of both a speaker and a hearer (Goodwin, 1979, 1980). I showed that when speakers find they don't have a hearer they produce a restart in their talk and that gets a hearer to look. Thus, the original work presented it as a sequential phenomenon, but I think that looking at this within a narrow sequential framework distorts its importance. The crucial thing was that the utterance is constructed through the simultaneous work of different participants occupying different structural positions and contributing to it by using different materials to constitute what they are doing. In other words: yes, you have got the talk of the speaker; but you also have the embodied orientation of the hearer. Through and through we are social creatures. In fact, what I want to argue is that the key transformation that made us human was not in the first instance a change in the brain or new psychological states, but instead a transformation in the nature of human sociality. And that is partially what I want to look at today: We inhabit each other’s actions.

In my early work I introduced the distinction between knowing and unknowing participants (Goodwin, 1979, 1981, 1987). This has now become a major research topic in terms of epistemics, and I am very sympathetic to this work. But the way that conversation analysts investigate epistemics, is largely people's claims to knowledge. However what I was looking at, originally, was the ontological constitution of different kinds of actors through the actions they were engaged in. One of the things this paper showed was that when a knowing speaker moved to a knowing recipient, they displayed uncertainty; they had to reshape themselves. It was this action-relevant constitution of different kinds of actors that at least initially was the crucial point of this distinction between knowing and unknowing participants, or as it is now sometimes called K+ and K-.

2. Lamination: Layers of Diverse Semiotic Fields

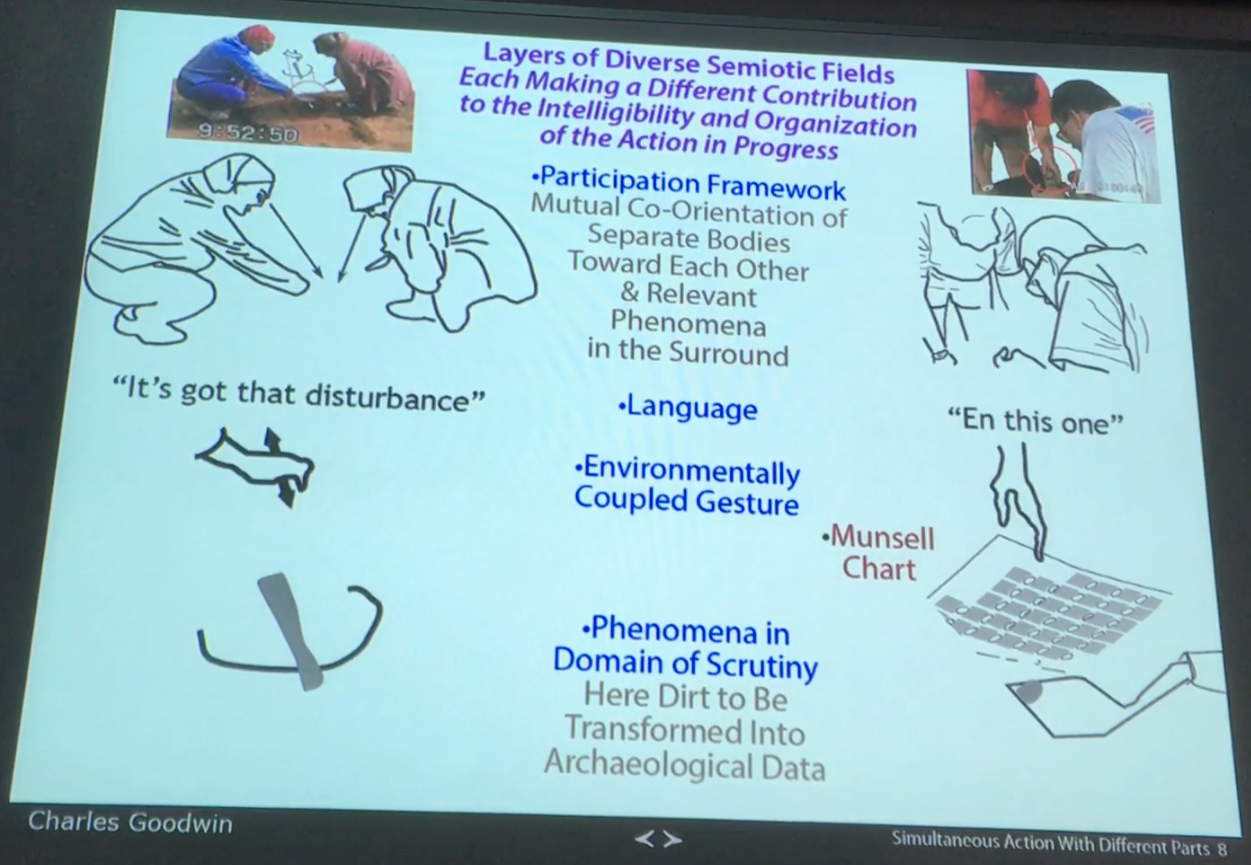

One way of getting a clear picture conceptualizing how actions are built from different things is what I talk about as lamination. A first example of this is one of my favorites and I use it way too often: The Munsell chart (e.g. Goodwin, 1994, 2000b, 2013). These two archaeologists have to classify color by using this Munsell chart, something I call an architecture for perception.

Figure 2

This action is built through the multiple usages of all of these different resources. We have the participants' bodies creating a shared focus of orientation towards each other and towards the things they are working on. We have language. We have what I will look at in a moment as an environmentally-coupled gesture. We have the Munsell chart. And the thing that I will pick up on in a different way later in this talk is that the Munsell chart was not created by these people. It is an historically structured architecture for perception. It was created by others, but it can suddenly be slotted into this immediate local action. In these ways, even in the midst of our local action, we are building upon the resources that we have inherited from our predecessors. And last, finally, there is the dirt itself that they are trying to inspect.

3. Prosody and the distributed speaker

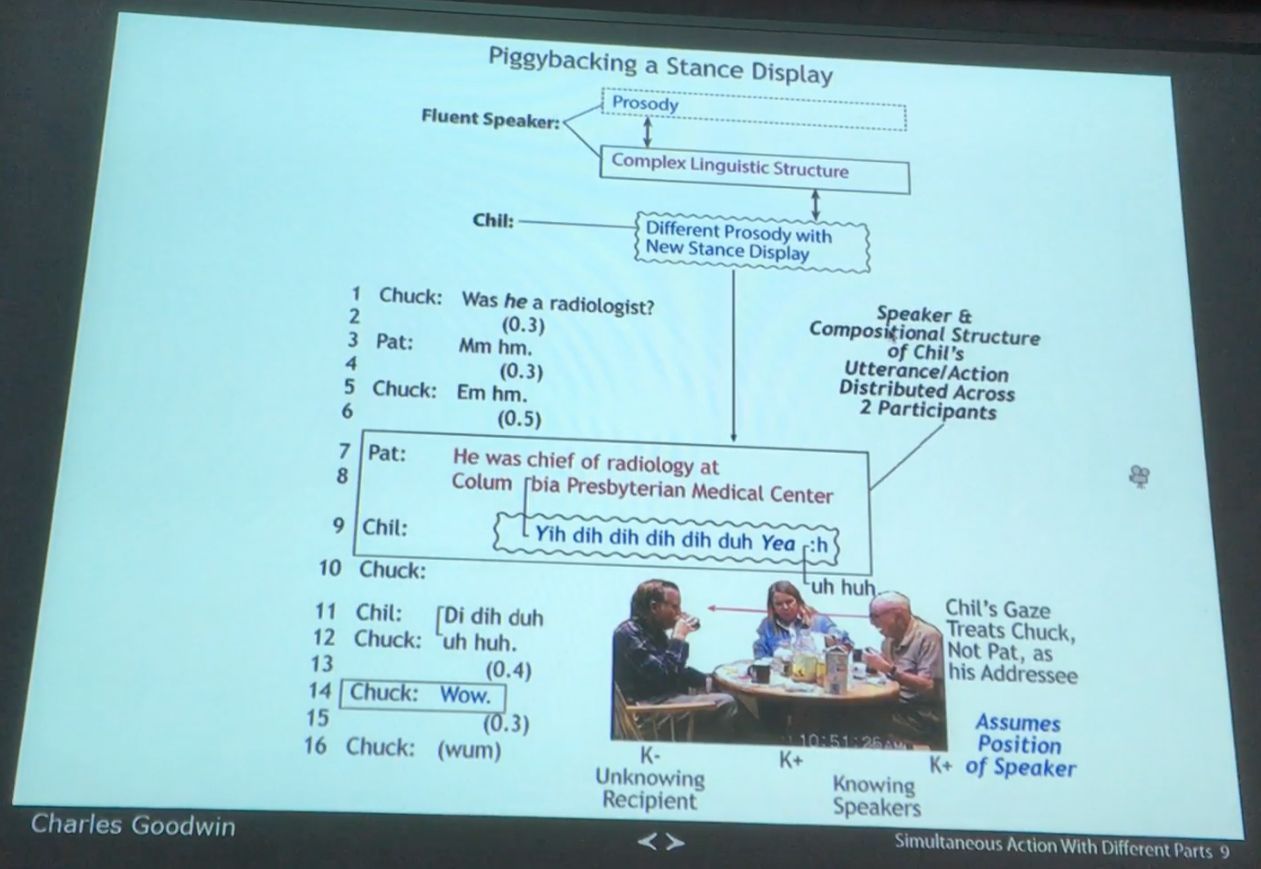

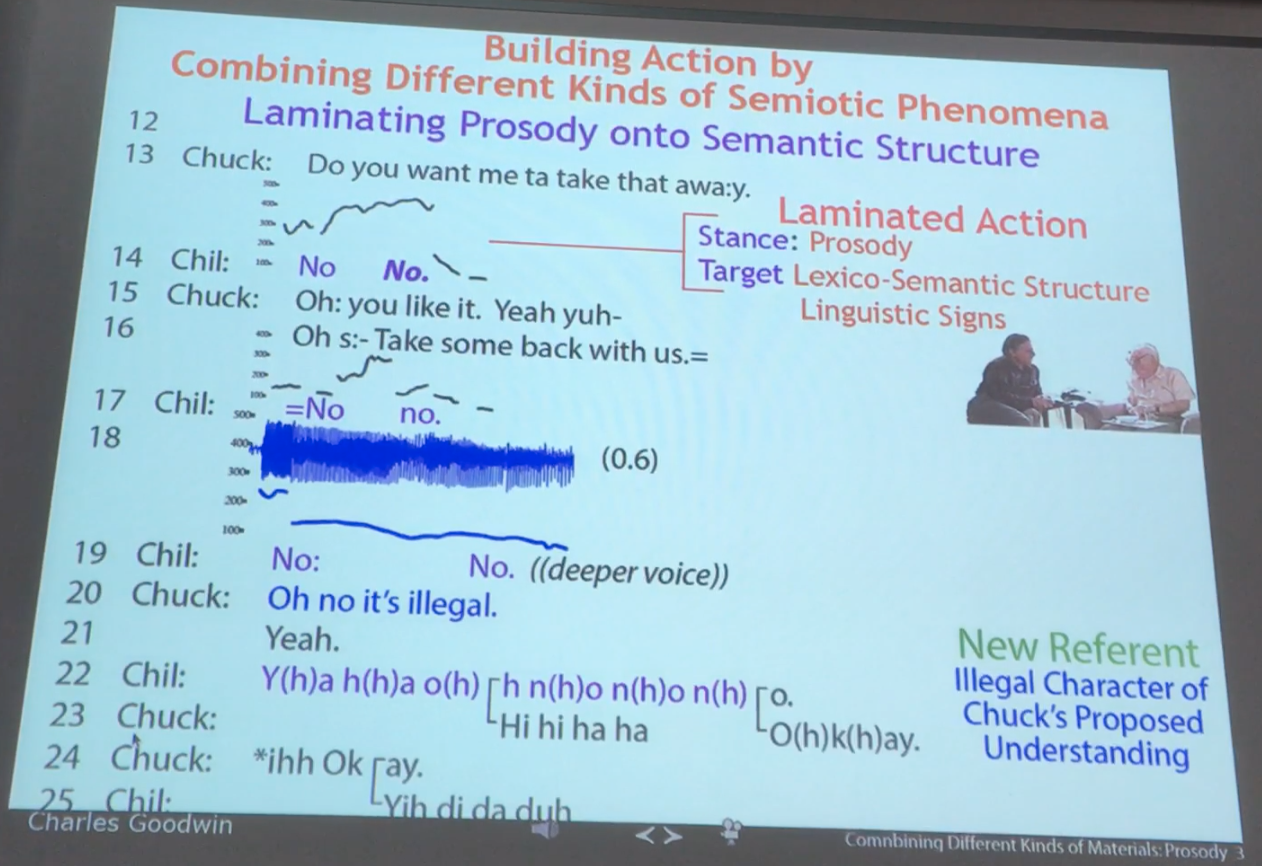

Here is a second example. Chil was my father and he could only say three words after a stroke, but he was a very rich speaker (Goodwin, 2000a, 2004, 2010, 2013). What we see here is how utterances are built through different resources.

Figure 3

Among the most basic resources in talk are lexical structure, or language structure, plus prosody. In this example we had been sitting and talking and I finally recognized that someone he was trying to talk about was one of his friends, and I said “Was he a radiologist?”. At that point my sister Pat came in and said, “Yeah, chief of radiology at Colombia Presbyterian Medical Center” which is a big hospital in New York. But she said it in kind of an ordinary way. Chil then came in and said, “Yih dih dih dih dih duh Yeah”. With this he was saying, through his prosody, that this was a kind of big, exceptional guy. And I in fact respond to that in the end, not to what my sister Pat says, but with saying “wow”: I respond to the inflection he is giving it by transforming the prosody. By doing this, Chil has delaminated Pat's talk by replacing her prosody with his own.

This example reflects a main thing that Chil did, and how he managed to be a powerful speaker. He got other people to produce the rich language structure he needed, and he appropriated, re-used with transformation, indexically incorporated their rich language structure so that he could make complicated utterances with almost minimal words.

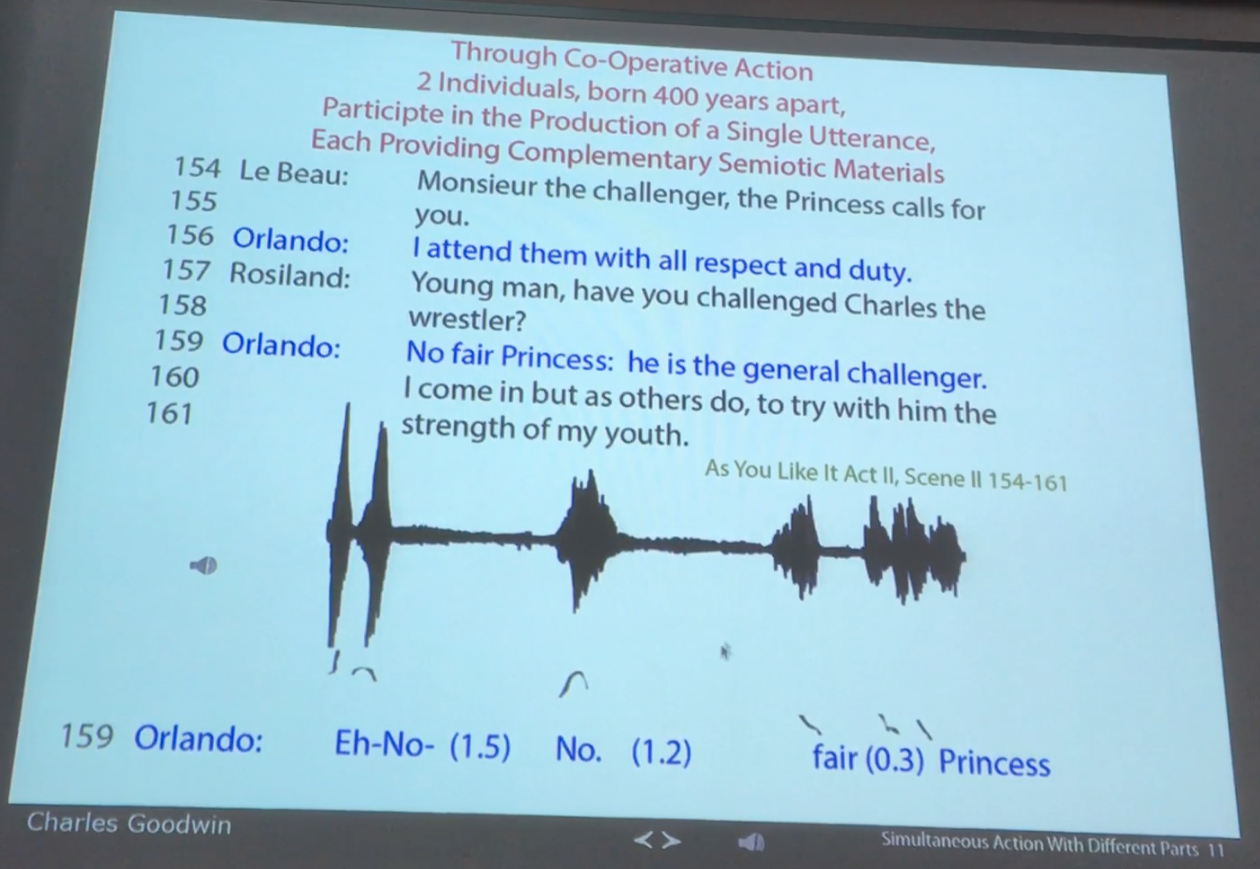

Figure 4

A third example, demonstrating how this spans hundreds of years. This is a line by Shakespeare from As You Like It, and what is going on in this play is that this is the moment when Orlando meets Rosaline and they fall madly in love. It is crucial they fall madly in love - but that is not in the text. The audio is from a BBC radio recording of the play and what I want to indicate is that the actor creates the action of falling in love through the prosody through how he speaks the words that were written by Shakespeare four hundred years ago. Just as I am trying to argue that actions are built from different parts, in this case we have two actors living four hundred years apart producing a single action that each contributes something different to that action in the local moment.

Coming back to Chil, first of all this is another example of an action that is built by laminating prosody on top of lexical structure. Another thing that we see in this sequence is that Chil was using exactly the same lexical items - “No-no”, several times. But with each one, he produced a whole bunch of different actions (Goodwin, 2013). In this example, we had just eaten some grapefruit and he was trying to get me to do something. He pointed down at the bowl and then pointed straight forward and then repeated these two points several times. It was clear to me that he was trying to get me to do something - and I could not figure out what it was.

Figure 5

One point that I want to make is I could not understand any of the other “no-no’s”. All the other “no-no’s” were about what he wanted me to do and I did not get that. Then, through the shift in prosody, I could recognize that he was now talking about what he had just said, making the point that it would be illegal to bring fruit back with us into California. I could in fact recover that action, and that was done with the prosody. As a result, he had actually constructed a whole bunch of different actions with this same lexical item by putting different prosody on them.

So how did Chil make meaning? He had a really limited lexicon, but in addition to that he had the rich prosody, and with that he was able to produce composite laminated utterances. Also, he made use of what I call indexical incorporation of other people's talk. In this example, you don’t hear “no-no” in isolation. What you hear him say here is “no, don’t take that away”. So by operating on someone else’s talk, he was able to incorporate their words and in that way fill his limited language structure with their rich language.

Now an important point I think the models we have in the field of Conversation Analysis is kind of a punctual model. We think of both the speaker and the utterance as being located at discrete places at discrete points in time, when in fact I think that much more generally the things that construct an utterance and even a speaker are distributed across multiple bits of talk and across multiple actors. The proper notion is not the individual action but an interactive field that is sustained through the co-operative action of different kinds of actors and which is unfolding through time.

In addition to what he was doing with the prosody, Chil also has complex gesture, which we will look at in a minute, and then he has got interlocutors who are actively making sense out of the thing he is doing. So I see human action as a knot of diverse, intertwined resources.

4. How did types emerge in the natural world?

Human action is constructed by co-operatively combining unlike materials. We will look at what I mean by that in more simple examples, but basically we perform operations on other materials, typically materials we have inherited from earlier actors, either prior speakers or predecessors – like the people who made the Munsell charts – to perform simultaneous and sequential structure-preserving transformative operations on a local, public substrate. A key fact about language in this regard is not that it is private and mental, but that it is public. However this does not in any way diminish its complex status and the complexity of the semiotic field.

So separate actors participate in different ways in the construction of each other’s actions. Looking a little bit more in detail at Chil’s pointing, I want to ask the following question: how did types emerge in the natural world? Going all the way back to Darwin and Wallace, you have the question of human exceptionalism. Wallace thought that human beings were in some sense exceptional: Darwin was arguing that it all had to be the same natural biological processes. I think they are both right, and I am going to try to show it. Human beings are really unique. We have taken over the planet – and essentially, we are destroying it. There are ways in which we are radically different. One of the things that seems to be radically different is language. I will argue there are some other things that are also quite different.

Just as a side line: if you want it to be biological, you can ask did anything like that ever happen before in the history of life? The answer is yes, but only once: the development of Eukaryotes, a type of cell that engulf another one without destroying the other cell. All of a sudden you have a complex structure built from different parts, and these different parts could do all sorts of different things. That transition was the basis of all multicellular organisms. This complex of cells being built from different parts only happened once in the history of life and it took several billion years. So it is an earlier example of something being novel and special, but through natural resources.

The thing that interests me is that you have got the symbiotic organization between these different kinds of parts that allow you to do all sorts of complicated things. And I think that one of the amazing things about human action is the kind of contingent ways actors can suddenly grab different resources at the moment and pull these resources in to do the things that they want. So I want to ask the question: how could this have happened in the natural world?

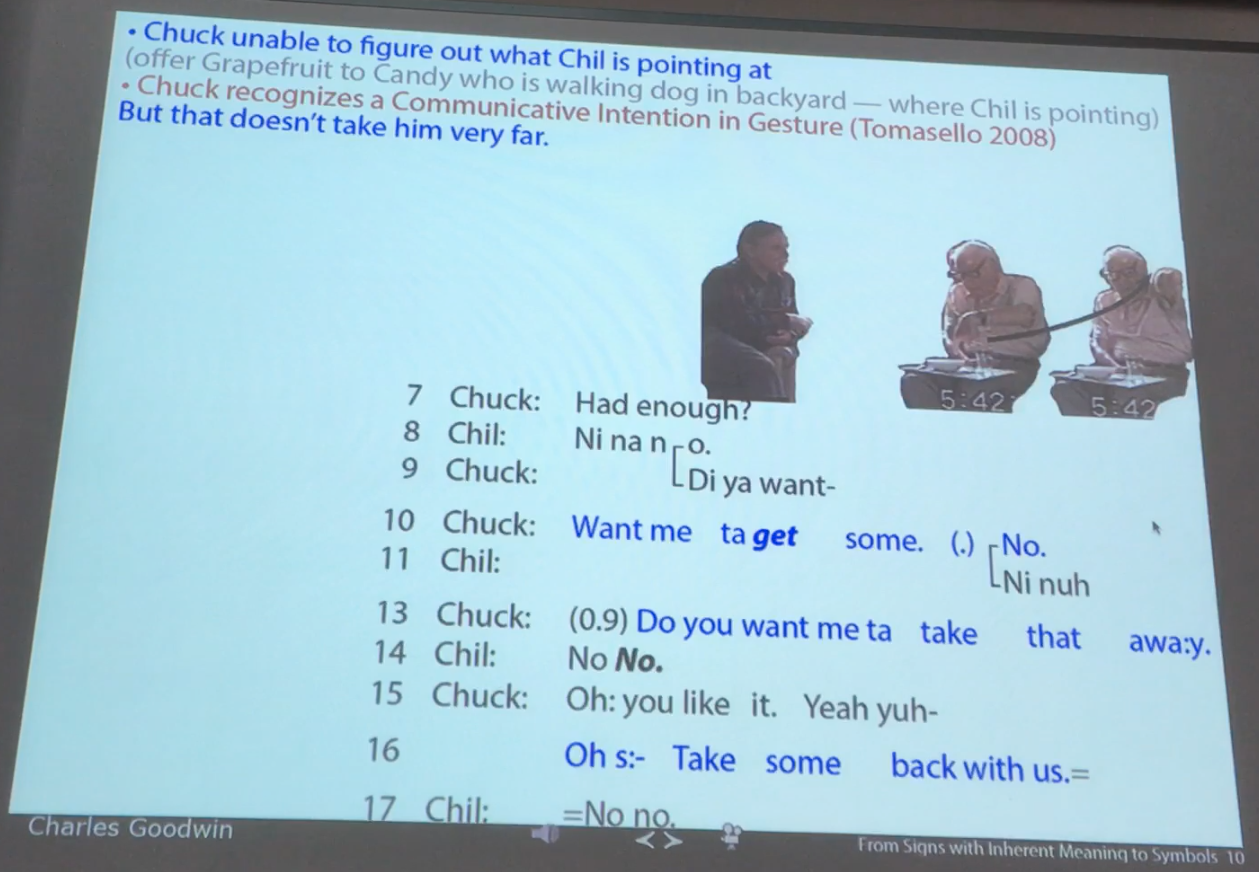

Going back to Chil’s gestures, he is doing two things. He is pointing down at this bowl with the grapefruit in it in front of him and then he is pointing off in this other direction in front of us.

Figure 6

I cannot figure out what he wants. I can figure out he wants me to do something, but I cannot figure it out. And if we look at what he has done, I recognize the communicative intention, but that does not take me very far. A lot of the work where people are looking at what makes us human at least in the contemporary world it is conceived of as in some sense psychological or neurological. A common thing would be the work of Tomasello and in different ways Searle (e.g. Searle, 1969; Tomasello, 2008, 2009). In different ways, they point to some mental state that would allow for human communication, such as recognition of a communicative intention, or collective intentionality. But they start from the perspective of psychology and as a result the addressee remains pretty much a figment of the speaker’s imagination. I want to argue that it is first of all a transformation in the nature of sociality, not psychology. What I am going to argue is that we, as a distinctive aspect of human sociality, have co-operative actions. This means that we have to build action in concert with others. We inhabit their actions. As a result, we have got to figure out what they are going to do every time we make an action. The fact that this is a pervasive social task makes that the locus for making inferences about what people are trying to do together. This provides the relevant environment for the emergence of what are glossed as ‘communicative intentions’ (ibid.).

What I am arguing for is an inherent sociality as the basis for these processes rather than some sort of transformation, psychologically. A second point related to that is the observation that unlike the Chomskyan idea of a single mutation, it can be incremental changes. I argue for a series of smaller changes that can be sustained because everybody has got to participate in it, making it a gradual incremental process sustained through sociality. Tomasello argues that gestures such as pointing are immediately obvious: one just points and you know what that person wants you to look at. He writes:

“Human beings [...] find such gestures as pointing and pantomiming totally natural and transparent: just look where I am pointing and you will see what I mean” (Tomasello, 2008: 1)

Well clearly that is not the case, as we just saw from this issue with Chil’s pointing. When Chill points, Chuck interprets the pointing in several ways. Sometimes, he is interpreting it as indicating the grapefruit, other times he is interpreting it as the bowl. Sometimes he is interpreting what is being pointed at as the kitchen, where you are going to take the dishes or get more grapefruit. Sometimes he is interpreting it as California. So you have got these massively different interpretations including being unable to recognize this close (Chuck points down in front of him very close to the table, eds.) what is being pointed at. Basically, and we only found that out later, Candy (Marjorie H. Goodwin, eds.) is walking our dog back in the yard behind the house, and he wants me to offer some grapefruit to Candy. I never got that, but the whole thing makes sense if you know that.

The problem I see with the theories proposed by scholars like Tomasello is that there is a whole theory that language might have emerged from gesture. And basically that theory takes a starting point in the observation that you have got all this meaning in gesture - so that would be the basis of language. I think there is a big problem with this, because there is a surplus of meaning in iconic and indexical signs, and so you have always got to figure out what each of those means in that occasion of use. The trick, then, is not to build from meaning, but rather go to the question of how do humans bypass inherent meaningfulness in order to move rapidly to a next action. Because what we find here is a range of meaning - it could be the grapefruit, it could be the bowl - that systematically delays the progression to a next action. This is not a problem in the same way with simpler forms of social action, like my dog wants to go take a leak and he stands by the door - and I can immediately figure it out. But with incremental development of co-operative action, the crucial thing is we have got to figure it out because we are building complex action in concert with others. This means we are beginning to get a whole bunch of contingencies, and then that more simple system starts to fall apart. It is a crisis, the crisis of surplus of meaning. And how could that crisis be resolved?

This brings us back to the question: how did Piercian symbols emerge in the natural world? Well, symbols are things that are recognized through convention or agreement. They can have resemblance, if you look at, for example, sign language. But basically you recognize them not because of their inherent meaningfulness, but because you have got a shared convention within a community. Once that is the case, and I say something like “sparkling water”, then you immediately know what I am talking about and we do not have to work it out. The result then is the possibility for immediate movement to a next action. So, going back to the grapefruit example with Chil: if he could have said something as simple as “Candy”, the whole sequence would not have been necessary. The point I am arguing is that an emerging framework of co-operative action provides an environment that would systematically lead to the emergence of a new form of semiosis: what we would call Piercian symbols. Or you could call it “types”.

5. Co-operative action promotes the emergence of semiosis

It is a new form of semiosis in the natural world. Moreover, because of the vast increase in the power of action with cooperative action, and because you can talk about things in the past and so on, once you have got symbols, then it would be sustained. And I actually think that the crucial problem in the evolution of language is the emergence of types. In a variety of ways, syntax follows rather rapidly once you have got types. Related to these questions there are experiments by people like Kirby etcetera. But I think the big question is, how do you get types in this sense?

Most central to the question of types, as I see it, is that they function in a community and by convention. You have got to have both parties operating on that bit of sound or whatever it is, in order to make the emergence of types possible. As Volosinov argues:

“Word is a two-sided act ... a bridge thrown between myself and another ... One end of the bridge depends on me, the other depends on my addressee” (Volosinov 1973:86)

In other words, you have got multiparty participation. Each party is operating on each other’s actions. If you are able to understand me, even though I realize that I am speaking fast, it is because you can recover some meaningfulness from the signs I am producing. And that is constitutive of a symbol. So what does that mean? Co-operative action sits at the center of human language, and symbols are essentially co-operative structures in which one party is operating on another. Another aspect of this is that everything is lodged within different communities, so you suddenly have the emergence of all sorts of diversity in the world. Which is another crucial feature.

What I have been arguing is that co-operative action provides an environment that would systematically promote the emergence of Piercian symbols and language in the natural world and then sustain them within the new forms of action they make possible. Let us look at another really simple example. This is again Chil, and here I got him some bagels.

Figure 7

Here Chil gives this prosodic thing and he points to the bagel. It’s like a proposition, like an utterance constructed through things. You have got the referent over here (Chuck points to the bagel) and then a statement about the referent. The statement is done iconically and indexically through the prosody. But I (i.e. Chuck in the video) have to go through a statement of saying “oh, you like it”. All that would be required within this framework is to put a word in there like “like” or “good” or the like. It could be any senseless thing. And because you have got this framework of co-operative action, you would already have the system for working out meaning between people through things like Schegloff talked about, like third turn repair (Schegloff, 1992). This is an environment in which signs can be developed and recognized through forms of agreement.

Next, let us just take a look at these two kitchens.

Figure 8

We are always inheriting resources: the left kitchen is in Chiapas Mexico, and I am deeply indebted to our colleague Lourdes de León who has worked her whole life with this community in Mexico. And the other one is Chil’s kitchen. Like scientific labs, these kitchens are sedimented resources for accomplishing an activity. The very fact that we are inheriting resources from our predecessors structures the way we use them. In Chil’s kitchen there is a whole bunch of stuff we recognize like stoves and packages and so on. In the Mexican kitchen you have a fire, you have a circular device for making a different kind of food – tortillas – and you have a different cohort: the women in the family here are all working together. These kitchens show us two different solutions to a common task. Both of them are re-using, with transformation, resources inherited by predecessors. So we have then accumulation through path-dependent change of co-operative action. This systematically creates an unfolding diversity of settings, languages, and cultures. If all of these are different - like I don’t speak Danish, I don’t speak Finnish or Swedish - but every time you have got one of these communities, every community is systematically faced with the task of building skilled, knowing members. There is this continuous process of constructing new skilled members, new skilled inhabitants, of a community. The question then is, how is that accomplished? Once again I think it is the compositional structure that does it.

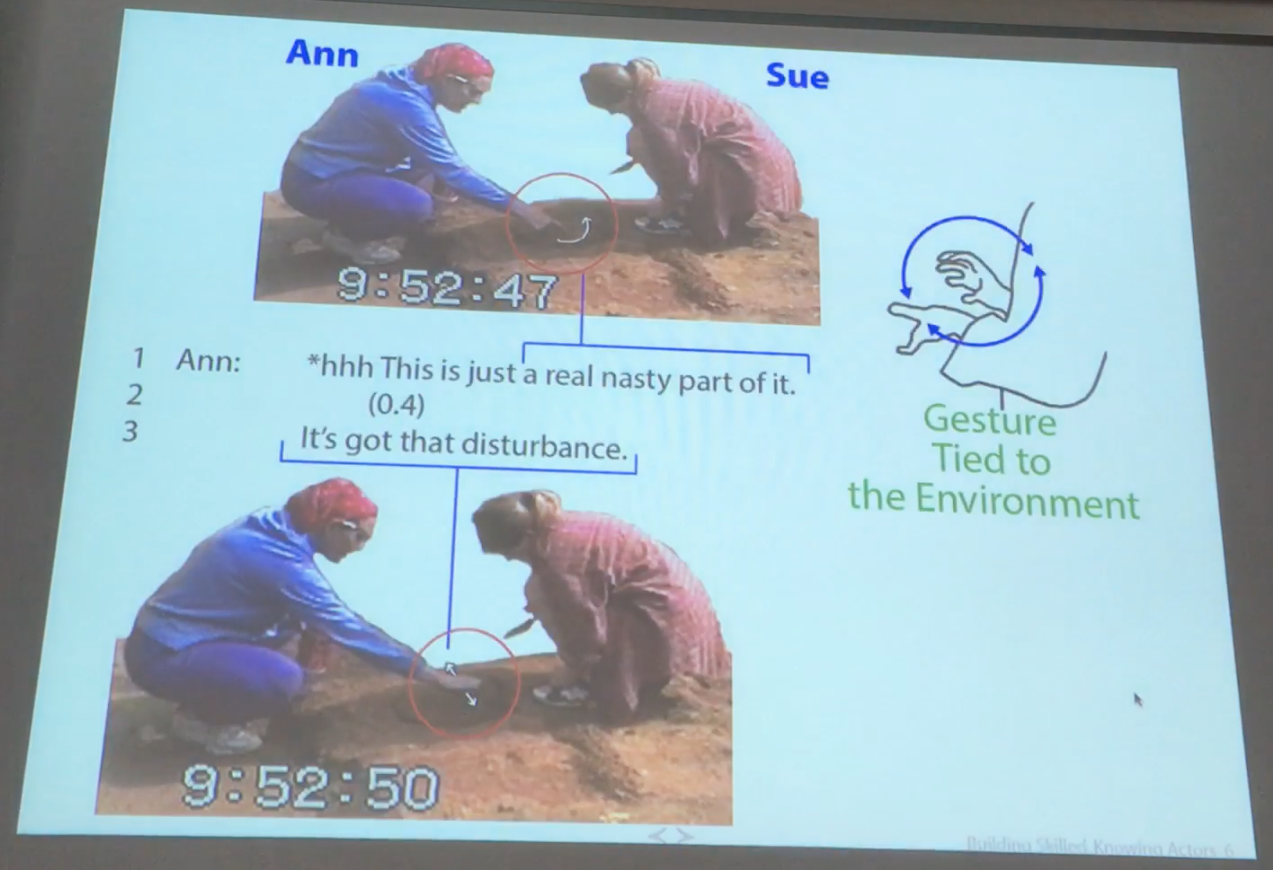

6. Building new skilled members: Environmentally coupled gestures

How do you make the distinctive phenomena that animate the life world of the community relevant to each other within situated courses of action? Here (see figure 9 below) is an archaeologist. Ann is the senior archaeologist and it is one of the very first days of the field school for this junior archaeologist, Sue, and she has to learn how to outline structure in the soil. There are all these marks in the dirt: one of these was probably an old hearth or maybe a post mold, but these shapes are visible only as color differences. What they have got to do is make a map, because they are going to destroy that pattern of dirt in order to get at what is underneath it. Now in order to make a map, you do something called defining a feature. You get a trowel and you outline the shape in the dirt. Then you transport it to the map, and that is what this student is in the process of learning.

Figure 9

During both “nasty part of it” and “disturbance” she runs her hand over the stripe in the dirt. It’s an action that is constructed simultaneously through language, through the gesture and through the meaningful materials that are being inspected and analyzed in the dirt. This next example is an utterance that was recorded with the Sloan Project (Center on Everyday Lives of Families, UCLA, eds.).

Figure 10

With the sound playing only, what you hear is, “so she sold me this but she didn’t sell this or that.” And we don't understand what is being talked about, even though we have all the language. If we add the gestures, we still don't understand it. But as soon as we see the object, we can immediately understand what he is talking about. It is a single action that is constructed through the simultaneous co-articulation of these different meaning-making resources. And it is the same thing that is going on with the archaeologists. What this tells us is that individual sign systems are partial. The meaning is constructed through the way in which each of them operates on the others. So the sense and relevance of individual signs are shaped through their participation in this larger package of meaning-making resources.

Now how is that relevant to the issue of building new members? When environmentally-coupled gestures bring together categories like “disturbance” or “post mold”, the dense phenomena are being categorized as part of the consequential activities that make up the life world of the setting. The issue at stake is how do we move from objects? How do we move from the dense materiality of the world into the types that organize the discourse of a profession? It is not just the signs. It is not just that you have got a semiotic system with types. You have this process of constantly negotiating the commerce between the world that we inhabit with all of its materiality and the types. And we have got to be able to negotiate our simultaneous use of both - and the commerce between them.

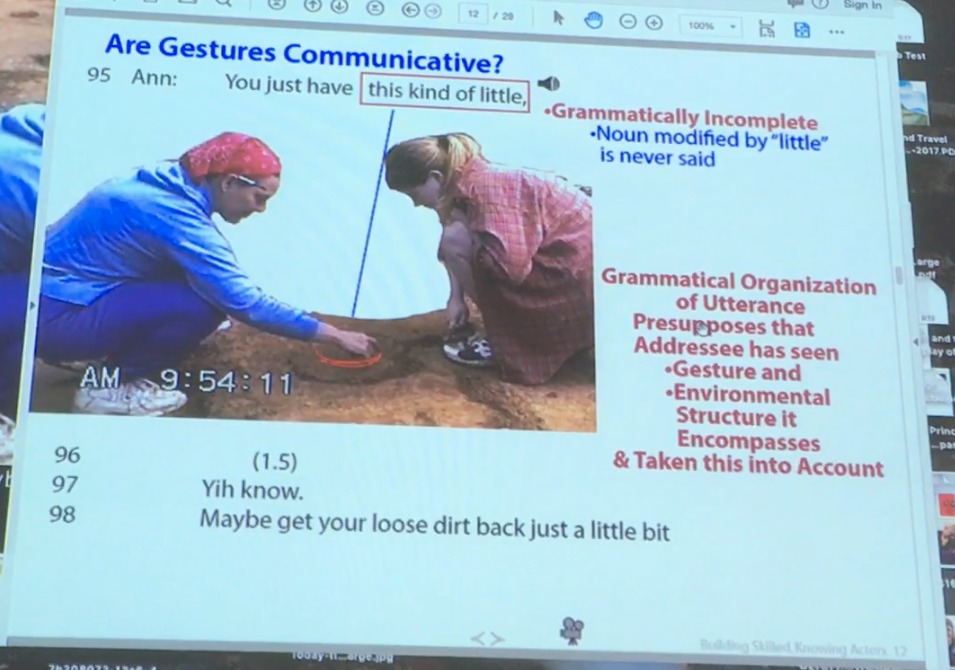

A second part of this is that people have argued that gestures aren’t communicative. If we look at the archaeologist again, she says “you just have this kind of little”.

Figure 11

“Little” is an adjective in English, so it requires a noun. But the noun never occurs, and this is not in any way treated as problematic. Quite obviously the student can see what the “little” is by virtue of looking at the dirt that is being gestured at. So the grammatical organization of the utterance presupposes that the gesture and the environmental structures it encompasses has been seen and taken into account. Kendon has called this shared orientation an F-formation (Kendon, 1990), and it is similar to what Candy and I call participation framework (e.g. Goodwin, 2007): they have got this embodied mutual orientation towards each other that then creates a framework within which other kinds of sign exchange processes or other kinds of meaning-making like gesture, talk and so on, can occur. In terms of embodiment, there are really structurally different kinds. Embodiment is a complex collection of very different kinds of meaning-making resources that are typically used together to build action. There is the way in which we are displaying our orientation: that is one kind. And then there are the things and actions that are being done within it as well as the prosody. That is another kind.

Archaeologists gesture all the time. Sometimes they also trace the outline of shapes (as in figure 12 below). If she lowered the trowel just an inch she would put it into the dirt, and as she did that gesture, she would leave a mark in the dirt. Then she would have made an inscription.

Figure 12

What are the consequences of making an inscription? It makes a more durable trace, one that can turn into the beginning of a permanent record of what that shape was. The big issue I want to get to here is: you have got a new student. How can you check whether she sees the world appropriately? How can you know whether she has got the proper professional vision, if in fact all you are dealing with is her private perception? One of the things that happens is that the inscription gives her seeing precise shape within a public domain. As I argued earlier, one crucial thing about language is that it is public and this is also a way of making things like perception public. At this point in time the line in the dirt is a liminal object. It contains a categorization: a precisely human-made shape. But it has not yet been removed from this very same field that it is categorizing - that it signifies.

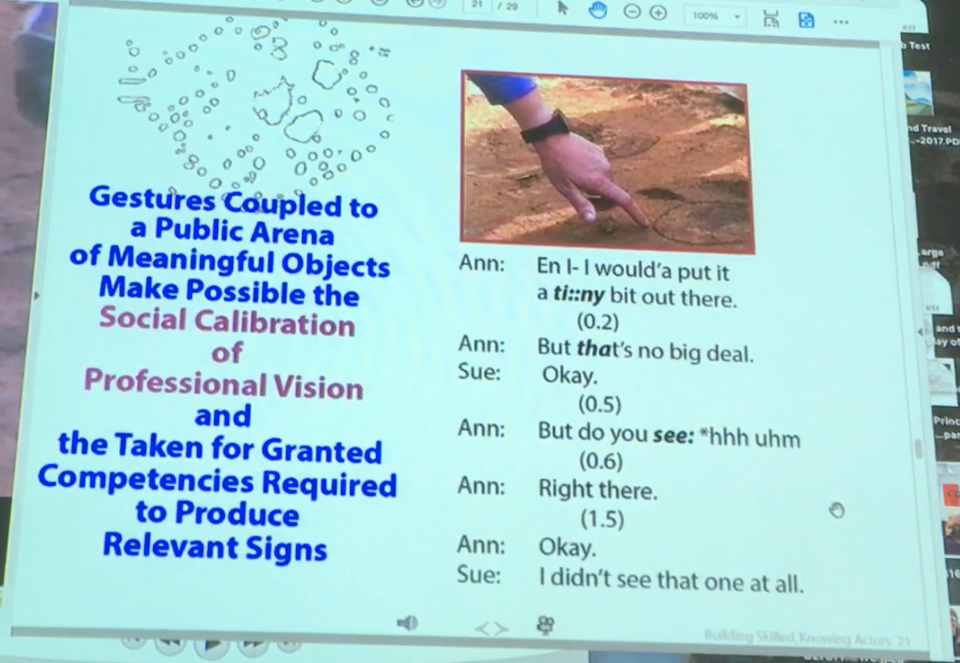

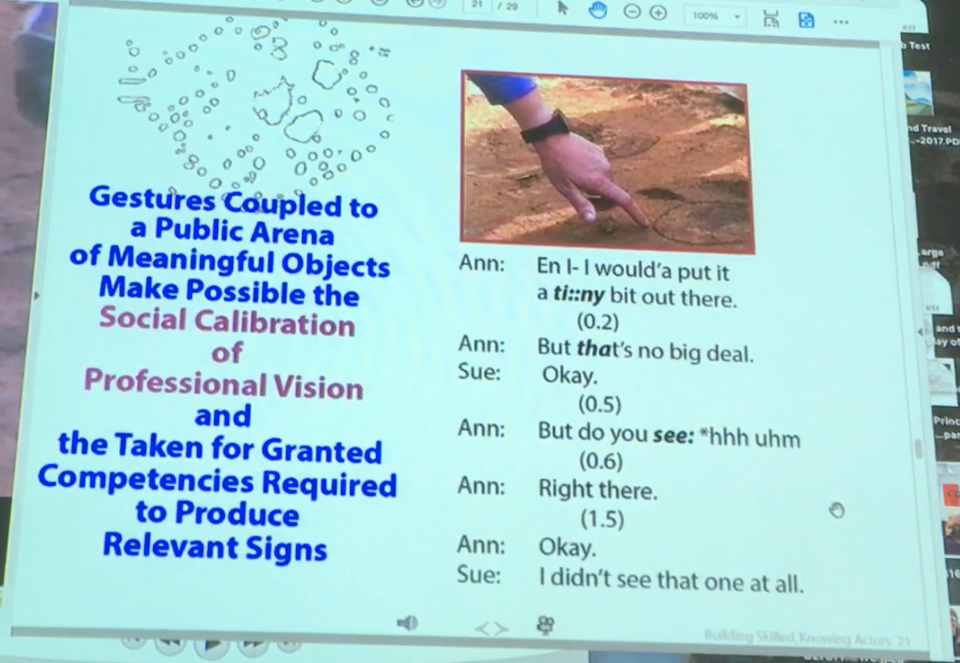

Figure 13

In the example, the student makes her mark, and then the professor says, “en I- I would’a put it a ti::ny bit out there” and draws a second line in the dirt, right next to the first. Again, co-operatively operating on what the student has done - but now you have this public calibration of seeing, a calibration of professional vision. The next thing is something that is found in a lot of good grad students in science: they do not just accept what their professors say.

7. Building new skilled members: Embodying the phenomenal categories of a community

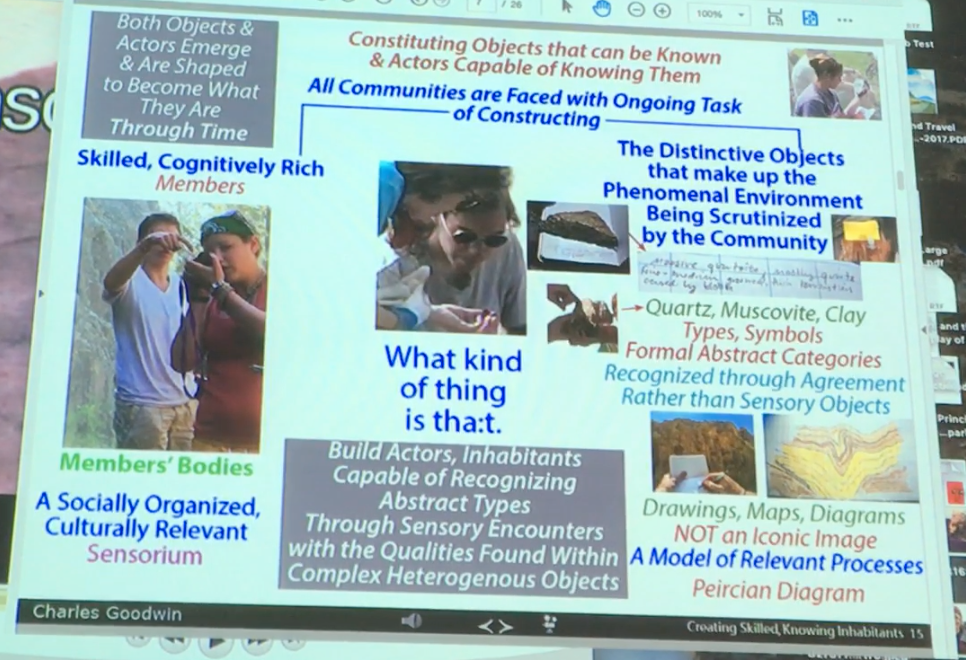

Now I want to look at a similar and more elaborate example. This is a group of geologists. A big problem in both geology and archaeology - and I have done a lot of work more recently with geology - is a basic question. It is actually - I love this question - what kind of thing is that? It is a basic kind of question.

Figure 14

In field schools you are systematically trying to create new competent members by working with a senior archaeologist or geologist. All communities are faced with the ongoing task of creating the distinctive phenomenal object that animates their discourse and action. In geology, they can be categories like Muscovite, or they can be these maps for the archaeologists. They can be types and symbols and forms of categories. But at the same time they are simultaneously faced with the task of creating skilled, cognitively rich members. Coming back to the question of epistemics, there really is this prior question: every community is faced with the task of building simultaneously both the phenomenal objects that organize its discourse (like in conversation analysis the adjacency pairs), but you have also got to build actors that are capable of recognizing and working with those phenomena in just the ways that animate the discourse of their profession. Most of these young geologists and archaeologists go off alone and somebody comes back with a map. As a senior archaeologist or geologist, I have to be able to trust the map they have made as I am not seeing the original thing anymore.

As a consequence, you have got to build actors capable of recognizing abstract types like the category Muscovite through sensory encounters with the qualities that make up complex heterogeneous objects. What I am trying to figure out is: then how do you organize the movement from individual qualitative experience up into the socially recognized categories that animate discourse on the level of types? I want to argue that - and this is an old phenomenological argument - both objects and actors are shaped and become what they are through time.

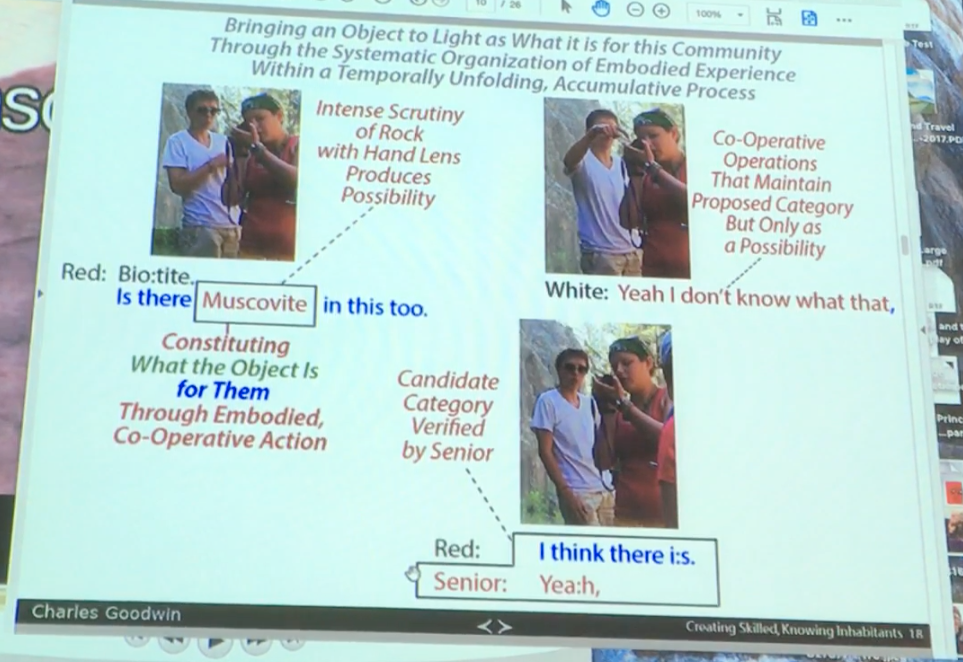

For the next example, some geology students are inspecting rocks. We are going out looking for rocks in the middle of Yellowstone, way in the back-country, and we have walked for miles. They do not know what the rocks are, but they have been looking for Muscovite, among other things, because Muscovite would mark kind of a boundary. So here is a student, and she is proposing this might be Muscovite.

Figure 15

The student (in pink) raises it as a possibility that it is Muscovite, and then another student comes in and says, “yeah I don't know what that is”. One issue here is they have to constitute what the object is, and this second student is constituting it as an object, while maintaining this as only a possibility. As a result, the object has a liminal status. And that is something I have looked at a lot with archaeologists, that they do not just jump to a categorization. They do a lot of work to hold an object in a liminal state until they have actually got the evidence for an appropriate categorization. This goes on with their drawings of maps, as well as with their categorizations. So they hold it in that liminal state. Now, white comes in and she says “yeah, I think there is.” At this point the senior guy comes in and he says “yes”. So now it is accepted that in fact yes, that is Muscovite.

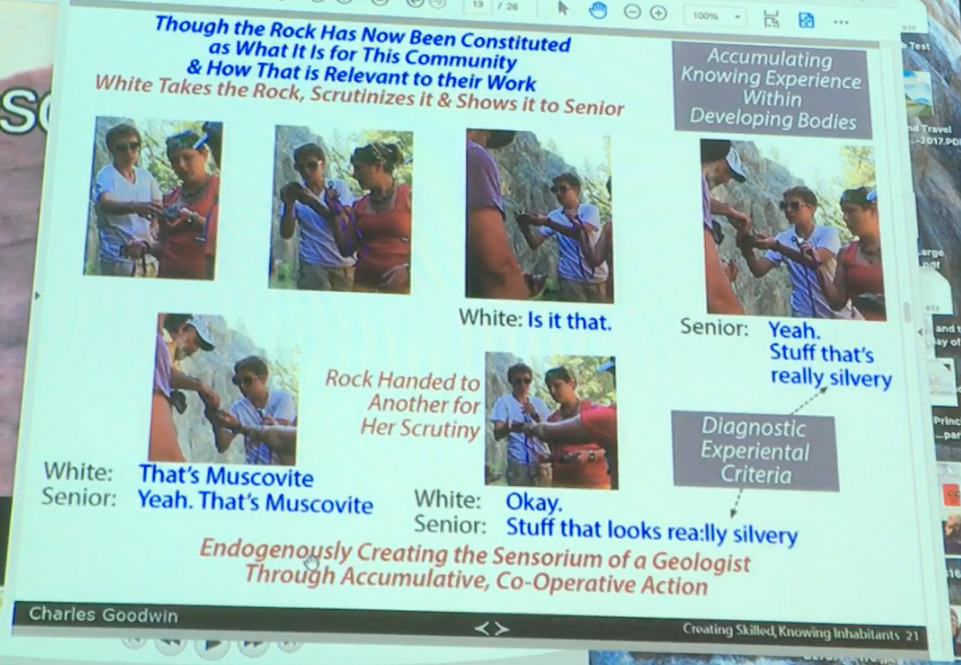

What is the action relevant category and what does it mean to make a category? In fact this has consequential meanings for what you are going to do next. If it is Muscovite, they are going to take a station (that is what it is called) – which is a big deal. If they take a station, they are going to have to cut up rocks and they are going to have to carry heavy rocks all the way back with them and so on. In other words it is relevant to their course of action through the categorization. They are not just recognizing an object in the abstract, they are doing it as part of these activities. At this point someone else comes and goes and grabs it and asks again, “is that Muscovite?”

Figure 16

Now that they have got a proper example of Muscovite, the others are using their own bodies to really learn how to recognize it. In this way, they are sedimenting the skilled practices required to properly recognize the object within a developing body and they do this within the framework of teaching with a more skilled actor.

8. The historical emergence of the co-operative ecology of meaning-making practices

What you are doing in both archaeology and in geology is that you are creating a sensorium that is public. Usually a sensorium is talked about in terms of our individual, private sensory experience. But here you have to create a public one, so that I can trust your qualitative experience to be mine - and this is the process we are looking at. In this way, what you are getting is not a single object but a general type. In order to do this you have to work out the token that counts as proper instantiation of that type through the public practice of a community. Again, what you have got once you have the emergence of symbols and once you have co-operative action is this accumulative diversity. That means that now you have got to develop new members as a systematic task in all communities. It is not lodged within the psychology of the individual but instead within a world of perception that is shared with other inhabitants. This is the more general argument concerning human action.

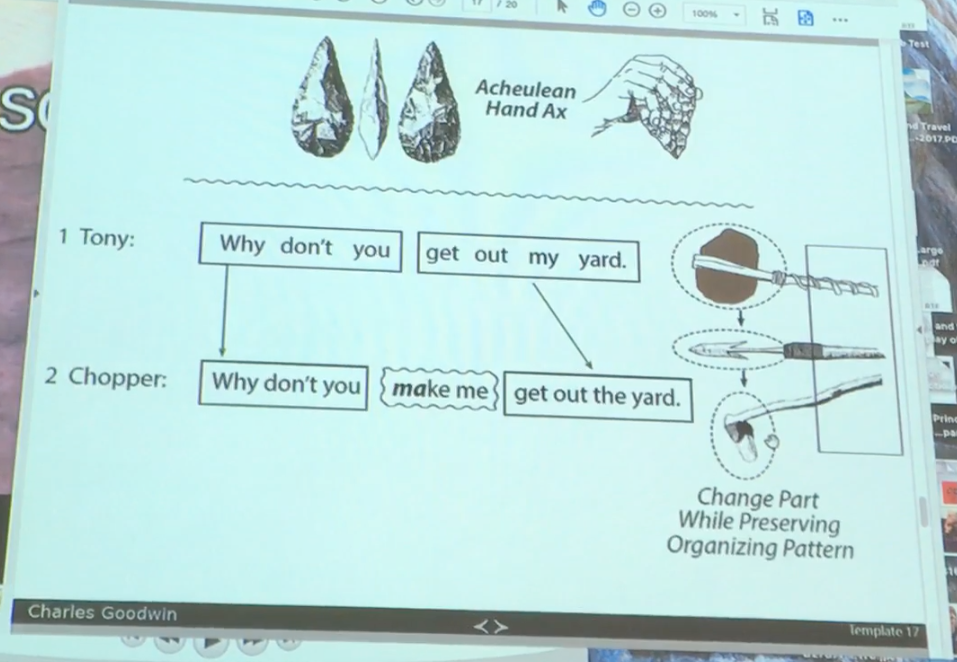

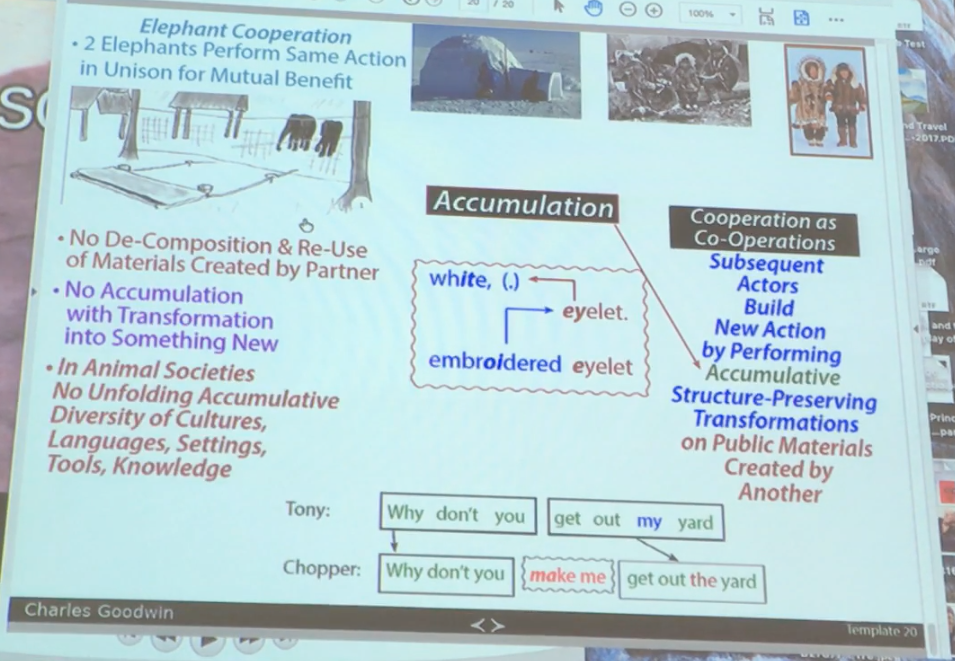

This next example above is from Candy’s data of the kids on the street. Great data: I love this stuff.

Figure 17

Tony gets up and says “why don't you get out my yard.” Now the thing about this is that it is built from different parts. We all accept that, being users of language or maybe even linguists. In the reply, Chopper says “why don't you make me get out the yard.” Now in order to do this, he has performed systematic operations on something that has been created by somebody else. I think it is a big problem with linguistics to just look at sentences as though they exist in isolation. Much more typically sentences are produced by operating on earlier talk. What is the nature of the operation? He tears the utterance apart and reuses some of it. He adds new stuff to it. But in doing that, he transforms it into something new. So you build new actions by performing accumulative transformations on a public substrate constructed through the work of prior actors: predecessors. Thus you are working within a framework of resources used by others. We inhabit each others’ actions while building a position that is uniquely our own.

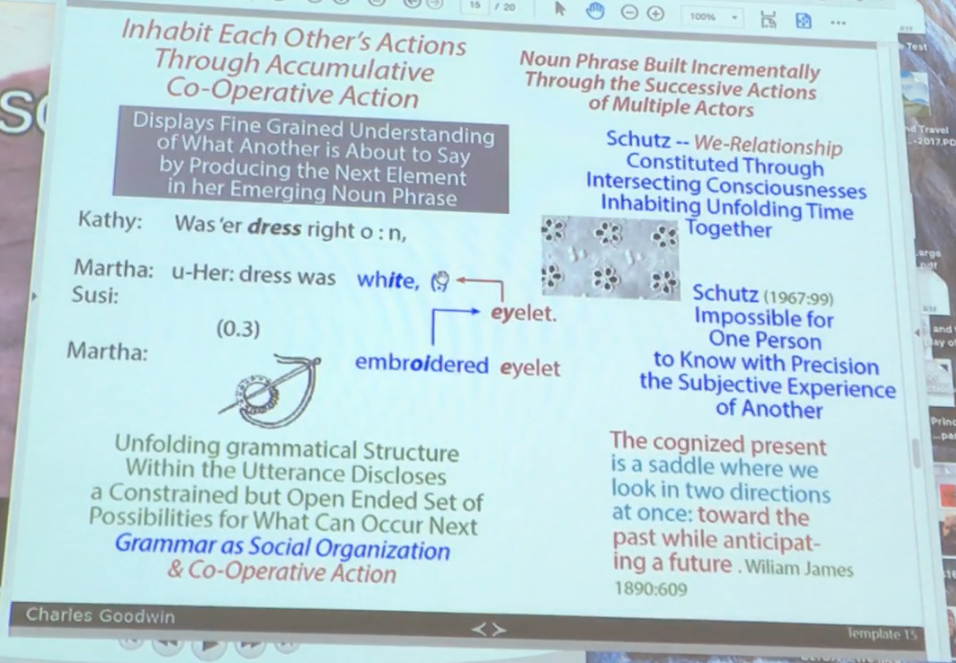

In this next example a family has gone to a wedding and Kathy, one of the daughters, was not able to go. She asks her mother, “Was’er dress right o:n,”. Martha says: “u-Her: dress was white” then hesitates. Then another daughter who did go to the wedding cuts in and says “eyelet”.

Figure 18

The unfolding grammatical structure within this utterance discloses a constrained but open-ended set of possibilities for what might come next. And what we are doing - and I think there is a major difference once we get language - we are inhabiting a punctuated version of the world that is constantly emerging and opening up horizons of new possibilities. William James argued that “the […] cognized present is […] a saddle-back […] from which we look in two directions into time” (James, 1890: 609). We can see that in this example. They look to the talk so far, and anticipate what could possibly become next. Now James is mainly talking about individuals. Schutz says we have got a we-relationship that is constituted by the intersecting consciousnesses of inhabiting unfolding time together (Schutz, 1967), and we see that: somebody else cuts in. These are people - again - in a public domain; their consciousnesses are intersecting and they are understanding each other through emerging language. But he also says it is impossible for one person to know with precision the mind of another person (Shutz 1967:99). Now Martha comes back and says "embroidered eyelet". The word she was looking for was not eyelet, but embroidered eyelet. The point I want to make is we have a single-noun phrase here that is constructed incrementally through the separate contributions of two actors. And moreover, that it is done through what I call Co-Operative Action. You are building upon the past that was there and visible in the unfolding grammar in order to construct possible next elements. As I argued also in the beginning, I don't see that this applies just to the language. It also applies to human tools.

Figure 19

Now the most successful tool in human history was the Acheulean hand axe. Forget the iPhone: it existed for a million years and it basically did not change. What I think, my proposal as to why it did not change, is that it was not built from parts so you did not have the possibility of progressive accumulation. I was having a good talk yesterday with a wonderful archaeologist from Aarhus, Denmark [Niels Nørkjær Johannsen, eds..], and we are both very interested in the emergence of humanity. And it seems you had incredible stuff going on at the Middle Stone Age that from my perspective was Co-Operative Action. You all of a sudden had a whole bunch of composite tools. You had a diversity of different cultures. You were exploiting different environments. You had a whole bunch of complicated stuff like bows that required particular arrows. Then the suggestion is that you also had to train new members - and you also had the emergence of language. But I do not think that it was simply language per se: it was this whole ensemble of practices that made us into modern humans. The thing about language is, it has got this grammatical structure, yes. But the whole thing is that language exists within a semiotic ecology of meaning-making practices. And that is what gives it its power. The real unit then is not language per se, but this ecology of meaning-making practices that I am trying to account for, that both accounts for the emergence of language and then the ways in which it can constantly have these new meanings – not just as a self-contained system (even though it has a certain kind of self-containment), but in the way it draws upon other things.

9. Why the hyphen in Co-operation?

Now why am I talking about this as accumulation and co-operation? Biological anthropologists say that two of the things that really make us distinctive as human beings are accumulation and cooperation, and I am trying to re-situate these. They try to look at these as a genetic metaphor; I am trying to re-situate these within individual practices. I am trying to say that it is a property of human action in general. And very quickly, when I am looking at it, it's not just cooperation. Within studies of cooperation it is defined in several ways - among others that it is meant for mutual benefit. But just take this classic study (Boyd & Richerson, 1988).

Figure 20

In the study we have these two elephants, and they have got some food in some cups, but the only way they can get the food is if both of them pull at the rope at the same time. If one of them pulls at the rope then the food does not get there. So they find out that they can do it, and the experiment shows that the elephants will do it together in consistent ways and it is argued to be an instantiation of cooperation. However, neither one of those animals is reusing with transformation the thing that was done by the other. Instead they are doing the same thing in unison. Then what you do not get, and what you do not get with animals in general, is an accumulative diversity of different cultures. You may have particular practices like washing potatoes, but that is that. So I think that the crucial thing that differentiates us from animals is Co-Operative Action.

References

Boyd, R. & Richerson, P. J. (1988). Elephants know when they need a helping trunk in a cooperative task. Culture and the Evolotionary Process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Goodwin, C. (1979). The interactive construction of a sentence in natural

conversation. Everyday language: Studies in ethnomethodology, 97-

121.

Goodwin, C. (1980). Restarts, Pauses, and the Achievement of a State of Mutual

Gaze at Turn‐Beginning. Sociological inquiry, 50(3‐4), 272-302.

Goodwin, C. (1987). Forgetfulness as an interactive resource. Social psychology

quarterly, 115-130.

Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional vision. American anthropologist, 96(3), 606-633.

Goodwin, C. (2000a). Pointing and the collaborative construction of meaning in aphasia. Paper presented at the Texas Linguistic Forum.

Goodwin, C. (2000b). Practices of color classification. Mind, culture, and activity, 7(1-2), 19-36.

Goodwin, C. (2004). A competent speaker who can't speak: The social life of aphasia. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 14(2), 151-170.

Goodwin, C. (2007). Participation, stance and affect in the organization of activities. Discourse & Society, 18(1), 53-73.

Goodwin, C. (2010). Constructing meaning through prosody in aphasia. Prosody in interaction, 373-394.

Goodwin, C. (2013). The co-operative, transformative organization of human action and knowledge. Journal of pragmatics, 46(1), 8-23.

James, W. (1890). The principies of psychology. Nova York: Holt.

Kendon, A. (1990). Spatial organization in social encounters: The F-formation system. Conducting interaction: Patterns of behavior in focused encounters, 209-238.

Labov, W. and Fanshel, D. (1977) Therapeutic discourse: Psychotherapy as

conversation. Academic Press.

Schegloff, E. A. (1992). Repair after next turn: The last structurally provided defense of intersubjectivity in conversation. American journal of sociology, 1295-1345.

Schutz, A. (1967). The phenomenology of the social world: Northwestern University Press.

Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language (Vol. 626): Cambridge university press.

Tomasello, M. (2008). Acquiring linguistic constructions. Child and adolescent development, 263.

Tomasello, M. (2009). Constructing a language: Harvard university press.

Volosinov, V. N., Matejka, L., & Titunik, I. (1973). Marxism and the Philosophy of Language.