Social Interaction.

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality.

Social Interaction.

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality.

2018 VOL. 1, Issue 2

ISBN: 2446-3620

DOI: 10.7146/si.v1i2.110037

Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

Objectivation practices[1]

Kenneth Liberman

Professor Emeritus, University of Oregon

Linkages between the early interactionist sociology of Simmel and Garfinkel’s ethnomethodology are explored, using illustrations drawn from the author’s research on coffee tasting, the debates of Tibetan scholar-monks, and players of board games. Garfinkel’s inquiries into the neglected objectivity of social facts are specified with concrete illustrations, and a model is developed to guide the investigation of some seminal topics in ethnomethodology. Discounting rational choice theory, voluntarism, and individualist models, this study offers an account of the objectivation practices that parties routinely employ when they collaborate in setting up an orderliness for their local affairs.

1. Introduction

Sociology is accustomed to acknowledging three founding fathers – Durkheim, Marx, and Weber. Whenever a fourth founder is mentioned, that fourth person is usually Georg Simmel. In many ways Simmel is the thinker whose original contributions to sociology have had the most pertinence for the inquiries of ethnomethodology, and this is because he recognized that the mundane affairs of everyday life are foundational practices for society. Simmel (1959a: 315) calls the activity by which individuals find themselves operating cooperatively “sociation,” and he considers it to be a topic that is both fundamental and intractable (Simmel 1959: 324): “There is no perfectly clear technique for applying the fundamental sociological concept itself (that is, the concept of sociation).” Simmel’s idea of sociation can guide us so long as we recall Garfinkel’s (2006: 161) caution that a “rough statement doesn’t tell us what we’ve found; it tells us what to look for.”

What is this thing “sociation”? Simmel (1959a: 315) writes, “Sociation is the form (realized in innumerably different ways) in which individuals grow together into a unity.” How do people develop or discover a unified canvas for, in, and as their mundane social interaction? It is this collaborative search-and-discovery project that is the topic here. Under what conditions and to what extent are members able or unable to affect things? I am especially interested in inquiring about whether anybody at any time knows just what they’re doing. In other words, to what extent are persons engaged in sociation “actors” in the sense that they are able to control affairs in a deliberate fashion, and to what extent are they limited to responding to emerging patterns and rhythms that temporarily surface in the hubbub that surrounds them? Simmel (1959b: 342) cautions us that the real action of sociation “does not consist of cognitions but of concrete processes and actual situations.” While much social science is preoccupied with concepts and cognitions, ethnomethodology has turned its attention to the most concrete, immanent things of the world.

It is for certain that I do not want to proceed by defining sociation and then to proceed from that definition. Sociation is too deeply embedded in our lives to be treated in a heavy-handed way; instead, it requires being discovered just-as-it-is and then specified “from itself in the very way in which it shows itself from itself” (Heidegger 1962: 58). Simmel only named it; he himself did not yet know what it was. Consider what he said about the obscure “minor” social forms that are at work in sociation, which he contrasts with the “major” or more macro social forms[2] that have captured the attention of most social scientists: [2]

"On the basis of these major formations – which constitute the traditional subject matter of social science – it would be entirely impossible to piece together the real life of society as we encounter it in our experience… It is really these minor forms that bring about society as we know it.” (Simmel 1959: 327)

I accept that these minor social forms are ethnomethodology’s fundamental data.

Phenomenology has informed these inquiries from the outset, and we should recall that Edmund Husserl and Georg Simmel were friends and read each other’s works carefully.

These well-used books authored by Simmel, which today sit on the shelves of Husserl’s books at the Husserl Archives in Leuven, demonstrate that Husserl took Simmel seriously and allow us to deduce that while ethnomethodology has learned a good deal from phenomenology, it can also be said that the sociological interest, and most importantly the interest in studying sociation that was later sustained and expanded by ethnomethodology, had some influence upon phenomenology. We should also not forget that Simmel is correct that these mundane social forms are obscure and that it is not easy to capture the details of these “everyday formations.” Ethnomethodology has made capturing these concrete local details into a discipline.

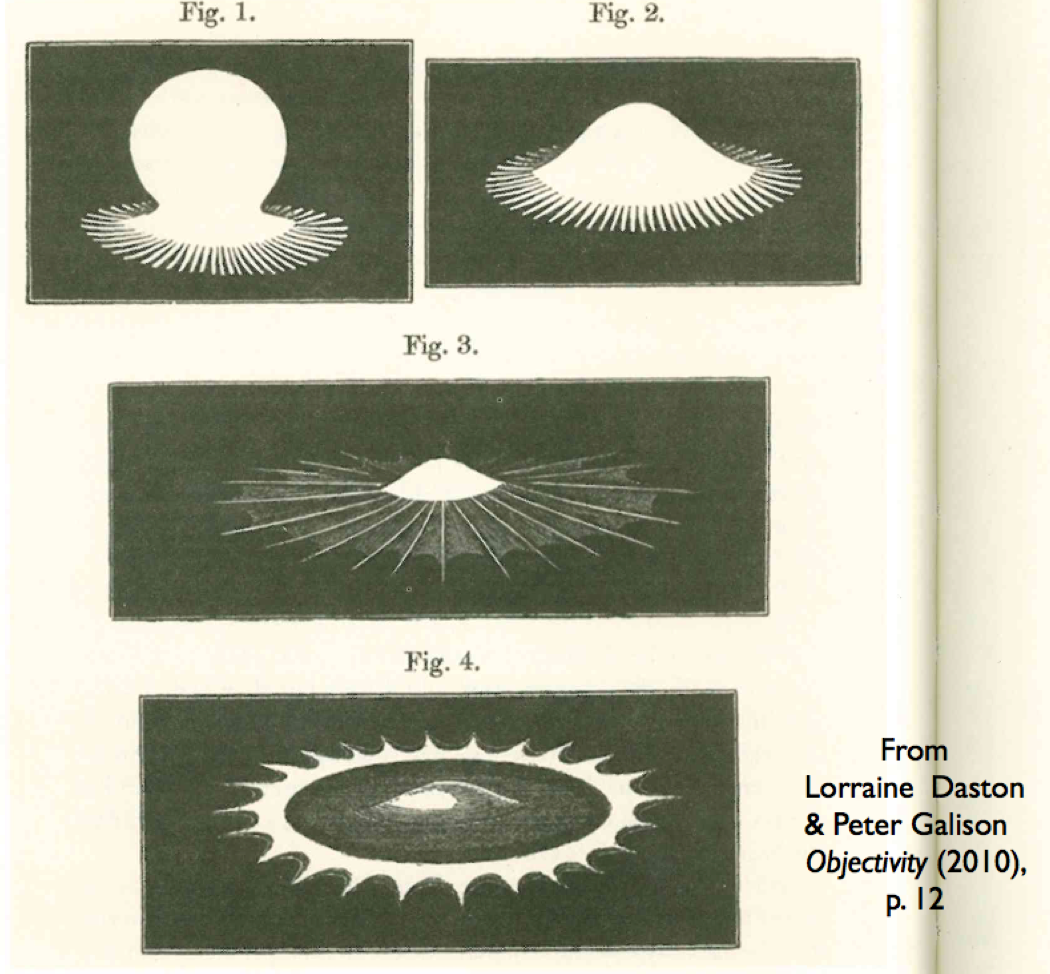

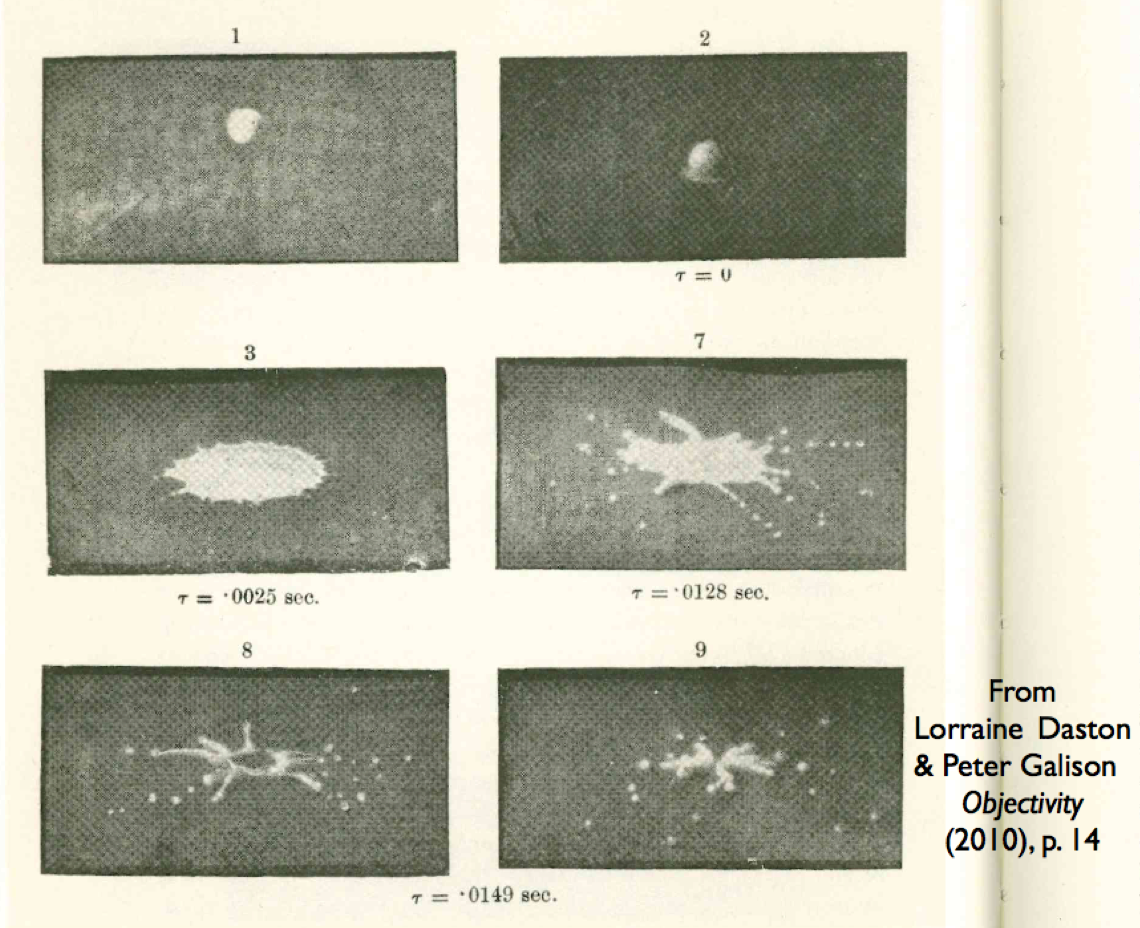

For the most part mainstream sociology has been disappointed with, and even resistant to, the messy but real details identified and described by ethnomethodological researchers. Daston and Alison (2010) located in 19th-century physics an illustration that is paradigmatic for our dilemma. From 1875 to 1894 a conscientious physicist, Arthur Worthington, had been making careful drawings of how different liquid media splatter when they hit a hard surface. In 1894, Worthington attempted to use the new art of photography to capture the details of how drops of various liquid substances splatter, because he believed that with photography he could capture those precise details even more perfectly. Much to his surprise, the real splattering was more disorganized and less coherent than what was presented by his ideal depictions. Daston and Alison (2010: 12 & 14) present the contrasting representations. First, here are the sketches of liquid media:

And then, the photographs of liquid media:

Worthington was disappointed that the real world offered less order than did his ideal representations in much the same way that mainstream sociology is dissatisfied with the results of ethnomethodological research.

2. Real-world phenomena

In the context of a Simmelian outlook, let us consider the aphorism invoked frequently by Garfinkel (1967: 33), “The policy is recommended that any social setting be viewed as self-organizing.” What does Garfinkel mean? In effect, it is a criticism of cognitivism in social science. Intersubjective affairs are unpredictable, and in spite of the many social scientists who imagine that our lives are more rationally motivated than they really are, events largely run themselves. This is an important change of perspective, and a postmodern one. As Garfinkel used to say, we have moved beyond rationalist just-so stories. The “reciprocal stimulation” that occurs (Simmel’s term, 1959a: 328) in intersubjective affairs is so dynamic that much of the time the participants gaze upon the affairs in wonder, barely able to anticipate where things might go next but keen to learn where that is, as soon as it happens. According to Simmel (1959b: 343) there is a necessary incompleteness to each situation, and this keeps participants anticipating.

Events are continuously in flux, and there are no time-outs. The flux of ordinary affairs keeps confounding us by exceeding our efforts to render those affairs orderly. And new rules are born every minute as part of our efforts to tame the situation or turn it to our advantage. As Simmel (1959: 328) tells us, “At each moment such threads are spun, dropped, taken up again, displaced by others, interwoven by others. These interactions among the atoms of society are accessible only to psychological microscopy, as it were.” It is ethnomethodology’s interest to provide microscopic scrutiny and to identify the endless entanglements of these recurring dislocations, which in ethnomethodology go by the following names: “no timeout,” “first time through,” “authochthonous,” “in vivo,” and my favorite, “the endless, ongoing, contingent accomplishments.”

In the 1960s and early 1970s some mainstream British sociologists dismissed ethnomethodology as a form of Californian subjectivism. This upset Garfinkel, first because never in his life did he think of himself as a Californian (in fact, he always hated the place); and second, because he was not a bit interested in subjectivity – already in his dissertation he had written about “the sterilities of subjectivity” (2006: 151). Instead, he called for ethnomethodologists to pay close attention to “the neglected objectivity” of social facts, and this is the principal clue that motivates the present essay.

Garfinkel (2002: 189) also proposed that, “Work-site practices are developingly objective and developingly accountable.” I am trying to elucidate just what is meant by “developingly objective.” In our efforts to tame our data, we must never lose the site of this “developingly,” and most probably even ethnomethodologists have yet to fully appreciate the actual flux of affairs. Like other people, ethnomethodologists are preoccupied with orderliness and with converting the flux of affairs into something more predictable, and this can lead them to proposing more order than is actually there. In everyday life most actors desire orderliness in their affairs, but they are unsure just how to accomplish it, and they end up stumbling into any ready-at-hand solution that presents itself in the course of their affairs. Moreover, people rarely seek a totalistic organization – they are not sociologists after all. Sometimes their interest in organization extends only as far as being able to cross the street.

As Garfinkel has taught us, members pick up from the looks of the world a method for organizing local affairs, and then they display for each other how such a method (a rule, a place in line, an opinion…) can be used to accomplish some orderliness. In other words, ethnomethods are instructable matters: people teach them to each other. But it is important to emphasize that in most cases these methods are stumbled upon, spotted serendipitously amidst the spectacle of the world. Only rarely are they planned with foresight; or, if they are planned such plans never quite work out in the way that is anticipated. That is the reason people to pay close attention to their mundane affairs, and it was this close attention that people pay that most captured Garfinkel’s imagination.

Even though these methods that people stumble upon and teach other assist them in organizing the orderliness of their local affairs, people still become entangled inside the local circumstances that these methods produce (Garfinkel 2002: 65). What has been astonishing in my research is to keep rediscovering that the ethnomethods lead the people rather than the people designing the methods by cognitive decision. Every line of communication becomes an entanglement, and yet the contingent circumstances set into play by these entanglements keep providing parties with further resources for organizing local orderlinesses by bricolage. Sometimes an ethnomethod can involve the use of any material thing that is at hand, which eases the task of organizing a local orderliness. By “a material thing” I mean things like blackboards, gameboards, Powerpoint, etc., but I also mean things like a phrase or a term that serves to get people onto the same page. Any device that is at hand can be made to serve the interests of cooperating parties in developing that unity of which Simmel is speaking.

3. An initial illustration

I offer the following illustration in order to make more clear this important point about ethnomethods leading the people rather than people leading the ethnomethods. Professional coffee tasters are faced with the naturally occurring task of rendering the wildness of the tastes of coffee more orderly and subject to remembering, recording, communicating, considering further, etc. They work to locate, identify and describe the principal tastes by developing a few taste descriptors that can carry their discoveries and effectively communicate them to other personnel in the coffee industry. The meaning of some of these descriptors is simple and obvious, such as “chocolate;” but others, like “balanced,” “round,” and “clean,” are not so well defined, and the descriptors function in part by collecting whatever a drinker is able to discover while examining the taste in a cup under the guidance of the descriptor. The sense and reference of these descriptors can expand and contract, and much of the important work of professional tasters is to tame the meaning of these descriptors so that they can be made reliable and assist the work of making taste more objective and precise.

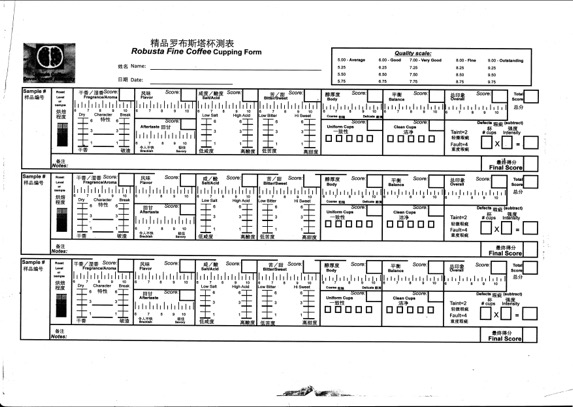

To aid them in such work, coffee tasters use evaluation charts that facilitate the translation of tastes into numerical, and thus hopefully objective, representations. These charts or schedules place something tangible in the hands of professional tasters, which they can then use to make their activities orderly, and I and my colleague Giolo Fele of the Università di Trento have spent several years studying how these charts are used, one sample of which is included here:

We used a simplified version of this chart to afford student lay tasters some focus for their evaluations. While our hope was that these charts would allow their thinking and discussion to be made more publicly observable to us and require them to verbalize their thinking so that we as researchers could follow their thinking more carefully, it did not work that way: instead of being used as a tool for exploring taste, the charts became a device for creating an orderliness that facilitated their being able to get on the same page in the social interaction that accompanied their tasting. The tasting itself and the flavors that the tasting identified, were relegated to a subsidiary status. In the end, the rating charts ended up governing the interaction not because it assisted their tasting but because it assisted them to organize a local orderliness for their social interaction and so render their interaction predictable and less risky. This is significant because it demonstrates that the cooperating parties’ immanent concerns with orderliness can have priority over the substantive objectives that their collaborative work was intended to address. Through a wide swathe of ethnomethodological and conversation-analytic research, what is most immanent in local interactional work supersedes more obvious items of business that may have motivated the social action in the first place.

Let us examine how this worked

here. The first of these five short clips shows the tasting forms being passed

out to the lay student tasters (not professional tasters) and displays their

initial examination of the charts:

The Numerators 1

With these forms in hand, the lay tasters proceed through the first of three rounds of tasting, one for each cup of coffee they are evaluating:

The Numerators 2

Despite their task, they discuss flavors only briefly. Given the tasting schedule, they quickly reduce their evaluation to a numeral for entry on their form. The form affords them the opportunity to render their interaction orderly and to quite literally arrive on the same page. As we can learn from The Numerators 2 clip, which does not require a translation, they quickly adopt a protocol of discussing only numbers. How does that come to be the accepted protocol? That is never discussed by the tasters, and no proposal about doing so is mentioned. The course of affairs themselves simply lead the participants into what is, practically speaking, a numeration-only ethnomethod for providing orderliness for their work of tasting, and their work quickly becomes reduced to the task of filling out the numeral-based form.

Even when their numerical

evaluations differ, they do not discuss those differences in terms of flavors:

they speak almost exclusively about numbers, and this is so even while they

are uncertain what is the meaning of those numbers. They are distracted

from the serious work of tasting by the apparent orderliness of numeration.

There is no calibration of these numbers, which is a necessary and vital step

in professional tastings, at least until the second round when the naturally

occurring comparisons between the first cup and the second cup allow their

numbers to acquire more specific meaning. In the second round they taste their

second coffee (The Numerators 3), and they numerate with more confidence, and it

seems that they appreciate the safety that hiding behind these numbers affords

them. Some categories that are given ratings, such as “balance,” are things

about which they have little understanding. Their assessments regarding

sweetness (dolcezza) and velvet texture (vellutato) display a

gross kind of evaluating, and the tasters generate their numbers with minimal

discussion, often nothing more than a “Si!” (yes). The Numerators 3 By the third coffee that is tasted

(The Numerators 4), the comparison practice has become more refined, and the robust

character of their practice of numeration is evident in the fact that they

discuss only numbers, and their growing confidence with their ethnomethod obscures

the fact that their method is facile.

The Numerators 4 The tasters have barely learned a thing

about the coffees. What is more, because they are not really discussing the

tastes they are locating, they are unable to teach each other anything either. Here

is a translation for part of their discussion in the final clip, “The Numerators 5” (5:16-27), during which they are assessing the “sweetness”

aspect of the coffee without ever considering what it can be for a drink like

coffee, which is characteristically bitter, to be sweet. Their numbers gain

some practical currency by virtue of contrasting the evaluations from the earlier

two rounds of tasting with the present coffee. They decide upon a number, and

then proceed directly to the next category: A Il primo era 5. The

first was 5. B E secondo? And

the second? A Secondo 9. The

second 9. C Un 7! A

7! A O.K. … “Vellutato”?

… The tasters have lost the phenomenon

(Garfinkel 2002: 264-67). Importantly, and as Garfinkel might have observed,

they have not lost the phenomenon in any which way, they have lost it specifically

because of their use, as an ethnomethod, of the “metrological” work (Garfinkel

2002: 284) of their numerating. By metrological Garfinkel is referring to the

use of measurement practices for providing a definitive characterization of the

inherent properties of the phenomena under examination and for providing an

orderliness for their practical work on any local occasion (Garfinkel 2002:

270). In the final clip, the tasters have even become satirists regarding the cavalier

character of their numerating: note that the rating of “seven” (“un sette!”)

is offered in the manner of self-satire. The Numerators 5 They have lost track of their agenda. They

may not even have had an agenda, but were simply engaged in looking to the

others and waiting for the situation to present them with an agenda. If we do presume

that they had an agenda, which was to evaluate the coffees they were drinking,

then they have lost track of that objective. They are caught up and become entangled

in the very metrological procedures that they are using for providing

orderliness to the local occasion. They have become “tangled in circumstantiality”

(Garfinkel 2002: 65). Examples of becoming tangled in

circumstantiality abound, and as soon as I noticed this phenomenon I have been

discovering it in nearly every bit of data I have collected during my various

research projects. Let me offer another case here: when people ask a passerby

for street directions it can happen that the reply includes many details that

are not helpful for learning the direction and that distract the parties who

are asking for directions so much (i.e. so entangle them in peripheral matters)

that they fail to talk about, and occasionally even fail to recognize

themselves, the inadequacy of the directions that were elicited. For instance,

in some case studies that my students and I collected in Buenos Aires, two

pedestrians walking across a part of the city asked a passerby, “How do we get

to Lezama Park?” The passerby replied, “Take the 168 or 64 bus from Pueyrredón Street.”

Instead of their replying, “But we’re planning to walk,” in order to elicit

advice that would be more pertinent to them, in an effort to be cooperative the

parties simply repeated the last few syllables of the passerby’s utterance, “en

Pueyrredón,” along with an accompanying nod of their heads followed by a friendly

“Gracias.” That is, they became caught up inside the agenda of the passerby and his reply, from which they were either unable or unwilling

to extricate themselves. One might say that they showed deference to the

autochthonic, emerging social structures of the occasion. Very many instances

of soliciting directions turn out this way: the response is a divergence from

what the parties intended to ask, and yet parties do not ask again, or try to reformulate

their inquiry. The immanent requirements of the conversation distract the parties

from the task of securing the needed information. Garfinkel studied under Parsons, who in his

sociological practice employed what had become sociology’s standard trope of

the homunculus: people were turned into puppets, and the only thoughts they were

allowed to have were those that the sociologist was able to stuff into their

heads. The direction away from individualism, and rationalism, that we have

been taking for three generations now has become clear. In contrast to Talcott

Parsons, Schutz was insistent upon not being satisfied with theorizing society

and turned to examining some of the lived realities of everyday life. In

contrast to Schutz, Garfinkel came to mostly avoid even phenomenological

theorizing and turned strictly to studies of naturally occurring activities for

direction, even to the point of being accused of being an empiricist (Attewell

1974). In place of “production practices” Garfinkel began to speak of scenes as

“self-organizing” (and there is an echo of Parsons in this), which are

situations in which no matter how skillful members may be, they are not really in

charge of things. Finding one’s path through the

complexities of our quotidian life requires considerable ability on the part of

members, and ethnomethodologists like to examine each one of these artful

practices, much in the way a bird-watcher is keenly observant and eager to

identify and describe each newly discovered aspect of avian behavior. But in spite

of their artful practices, members proceed myopically – their vision is local,

even more local than local. This “more local than local” is what Husserl intended

by his word “immanent” in the definition of phenomenology he offers in Ideas

(1962: 161): “a pure descriptive theory of the immanent formations of

consciousness”. We are constantly attempting to find our bearings, and much of

the time no one is in control. The ethnomethodological investigation

proceeds from the immanent looks of the world from the perspectives of the

members trying to find their way together. Here I investigate how events

organize themselves, and I try to appraise to what extent and under what

conditions members are able to affect things. Parsons presumed too much. Schutz

presumed too much. And on a few occasions even Garfinkel presumed too much. Since

we are academics, it is difficult for us to shed our rationalist blinders. In an unpublished 1962 paper,

in which Garfinkel first laid out his plan for Studies in Ethnomethodology,

he said that he would “treat … methodological interests of the members of

society as objects of theoretical sociological inquiry” (Psathas 2004). To what

extent do people really have deliberate, planned ahead of time, “methodological

interests”? They can have them, to be sure, but my studies reveal that

it is more common that they do not know what they are doing until a routine is

put into play as a collaborative and autochthonous event. In a 1965 version of the paper

(typescript), which was delivered at the University of Oregon, Garfinkel said,

“Persons, in the ways in which they are members of ordinary

arrangements, are engaged in the artful accomplishment of the rational

properties of indexical particulars.” At that early stage of ethnomethodology I

think we possibly idealized what was rational activity. It turns out that

rational activity is not nearly as rational as we were thinking at the time.

The notion “members” already undoes some of the individualist, deliberate,

controlling aspects of rational activity, in that it is an admission that

people are acting as a collective. Deliberate, voluntarist, rational planning

is not unknown, but mostly the events move too fast for planning to be very

effective, a phenomenon that always impressed Aaron Cicourel (1974), who

insisted in his field research that the basic structures of interaction were

always in the process of emerging. Once Garfinkel became absorbed

in studying scenic practices, i.e. in “studies,” he came to rely less upon

social phenomenological idealizations of decision-making and sense-assembly and

to emphasize more the authochthonous and tendentious nature of those affairs.

In the last year of his life, when he once casually used the phrase “production

practices” in a conversation with me at his home, I criticized the term

“production” by suggesting that it was too voluntarist. I said that yes an

orderliness gets produced, but much of the time no one is in charge, and the

orderliness that ends up governing affairs can be one that no one had in mind

in advance, so “produced” is not always an apt term to describe what is going

on. Garfinkel replied thoughtfully, “Yes, you’re right. Perhaps we need to give

up on the term ‘production.’” Even at an early stage Garfinkel (2006 (1948),

156) intuited this: “One runs the risk of

assuming a rational actor, and we wish to avoid this assumption;” and in the

same study he downplays “purposeful calculation” (160). So then he asked me

what term I would use instead. I replied that there is “congregational

work oriented to finding an orderliness,” but that we have yet to identify it or

describe it adequately. This essay is my attempt to move the ball further down

the field. 5.1. Intersubjectivity Aron Gurwitsch, a student of Edmund Husserl who was

brought to the US by Gurwitsch’s colleague Alfred Schutz, wrote about

“intersubjectively concatenated and interlocking experiences,” (Gurwitsch 1966:

432) but this too is only a phrase and not yet a specification. While

ethnomethodology has learned a great deal from Husserl’s theory of

intersubjectivity (elaborated for the social sciences by Schutz and Gurwitsch),

ethnomethodology has also learned that most of these intersubjective activities

are not necessarily planned, or necessarily conceptual. All three of these

phenomenologists acknowledged the importance of signs, but their reading of the

work of signs, while seminal, is perhaps too logical and conceptual to fully capture

the role played by the brute materiality of the signs that come to be possessed

in common by interacting parties, and that get used by parties to organize the

local orderliness of their affairs. Careful studies of micro-interaction have

revealed that these interconcatenations can occur before the meaning of

the signs being shared by parties is settled. Social phenomenological

perspectives that presume that a meaning always comes first, individual

consciousness by individual consciousness, and only then comes to be “shared”

or “negotiated” are mistaken. In fact, the meaning may never get

settled, should not get settled, and in most instances cannot get settled. Innumerable

social interactions take place during which parties operate with different

understandings of the same signs, or even with no understanding at all. This

situation is commonplace. It is our lives. How do the objective structures

of social interaction get worked out before those structures receive

their contents? Merleau-Ponty (1962: xx) offers us a clue: “Sense is revealed where my own and other

people’s paths intersect and engage each other like gears.” It seems that the course of affairs

serendipitously guides the participants to the competent coordinated social

interaction they seek. Ethnomethodology and conversation analysis share the

common aim of tracking just how these gears engage each other, that is, how the

microstructures can lead the parties to their solutions. In this sense, intersubjectivity

is more objective than it is subjective, and so perhaps a new name for

the phenomenon should be sought. The important point here is that the events

lead the way, and parties must continuously adapt to local structures that are always

emerging, with no timeouts. This perspective is not in any way a resurrection

of treating parties as judgmental dopes; rather, it proposes a specification of

what it is that artful practices consist of. The importance of members’ work is

not being diminished, but the idea that members always fully cognize just what

they are doing is discounted. Members are not Robinson Crusoes who know, as

individuals, each next step of what they are doing. The artfulness of their

organizing an orderliness is to be found in how they apply the tools that get

objectivated during the natural course of interaction and how they place them into

service for the local tasks of providing for intelligibility, order,

predictability, efficacy, and every other contingency of coordinating their

activities: it is not that they always know these ahead of the “inside-with”

tendentious life of their work. 5.2. Tendentiousness The “artful accomplishment” and artful practices that

were the focus of Garfinkel’s studies are not always highly planned doings;

rather, they involve members’ keen but opportunistic watchfulness for any

object that can be rigged to work for structuring the local affairs, or even

more basically, that can help them stay out of trouble, which is frequently the

first priority of parties on any occasion. In the early days of

ethnomethodology, we used to speak of society as “a floating crap game,” an

image that captures well the flux of our quotidian affairs. A social event

leads itself, and situations

are continuously in flux. Proust (2002: 60), observing the ever-changing and

fluid rules of warfare during his account of the First World War, writes, “War

is no exception to good old Hegel’s laws. It is in a state of perpetual

becoming,” and even today our generals complain that we are always fighting the

last war, which leaves us unprepared for fighting the present one. Like that,

“rules” are not as stable as sociologists once imagined them to be, and each

application of a rule happens first-time-through. More than to principles (which

operate as resources, much the way that rules do), peoples’ sight extends to

what is “next” and not much further than that. Our sight is myopic. Things may tend

toward a direction, but usually that direction is neither clear nor distinct. This

is its tendentiousness. It is such a “close-in” phenomenon that careless social

analysts can miss it. This can also go by the name of “the looks of the world.” In the Boston Seminars[3] Garfinkel spoke of “the

phenomenon as the interior course of its own production.” In other words, an

event drives itself with its own momentum; however, it may not be clear where an

event is heading. It is not that the people are not involved, but society moves

in accord with its own momentum. This is closely related with the “inside-with”

that Garfinkel speaks of in Ethnomethodology’s Program (2002: 271). People

can only work with the practical objectivities that emerge within each

occasion, and one thing leads

to a next. In our absorption inside the local circumstances of each occasion,

memories are short. Doug Macbeth, from who I learned to better appreciate this

notion of tendentiousness, informs me that, “It is heard in a first

which second is called for, and every present turn instructs what it calls for

next.” It is this “nextness” and the horizon of this nextness that identifies

the tendentiousness of affairs, and this is related to the flux of social interaction

that I am describing. Put in a different way, people

pattern after each other, and they pick up ways of formulating and ways of

knowing that follow from the previous speakers. However, they frequently misread

a previous speaker and so inadvertently carry affairs off to a new hinterland

that was not anticipated by anyone. The “floating crap game” aspect is that people

must pay attention to these new hinterlands that keep arriving on the scene. Macbeth also reminded me of a

passage from an important essay by Michael Moerman and Harvey Sacks (1988: 180-186),

“On Understanding,” where they are emphatic that turn-taking systems work “one utterance at a time.”

The immanence of local affairs always presses upon one, and what is most proximal

is the thing that grabs our attention. We are oriented to a “next,” but there

is only one “next” at a time! This limits the opportunities for longer-term

organizing, and solutions can become restricted to what is close at hand, to what

is immanent, without the bigger aims of social science always playing the

principal role. In short, we are overwhelmed by the swarm of the quotidian

events that keep heading our way. When Moerman’s essay was republished in his 1988 book, Moerman had in the end come to recognize

that understanding was not as straightforward as they had been assuming. That

is to say, even two of the most brilliant of ethnomethodologists had been

over-rationalizing intersubjectivity. Reconsidering his title during a brief

“1987 Introduction,” Moerman recommended changing the wording of “understanding,”

which had already become “what is called ‘understanding’,” to the more accurate

“the events that pass or fail to pass as understanding,” which offers us a much

more open representation of affairs, in the very way that the affairs are

open for the participants. In making this move, Moerman acknowledges that

understanding can fail, and that it is not rational in the strict way that we may

like to assume and in the way that the “decision sciences” would have it today. Ordinary matters can be left

up in the air, with no one certain, which is why parties keep themselves

oriented to that next. Because utterances occur one at

a time, the activities that serve

to organize local orderlinesses also occur one at a time, which results in

everyone having to remain oriented to what next may be impending. In the

immanence of this experience, people become myopic in their preoccupation with

that next next that must be handled, to the point that larger-scale

interests are lost sight of and even forgotten. (One only needs to recall how

quickly we are able to lose the focus that motivates one of our own Google

searches.) While macrosociologists are looking for the big picture in the way Simmel

describes, and the phenomenologists are looking for the big theories, the

parties themselves are preoccupied with not much more than looking for that

next next, since that is what they need to survive in the interaction.

While that may be too mundane for macrosociologists and phenomenologists to become

motivated to invest much of their attention to such a topic, because it is

critical for parties it is critical for ethnomethodologists. The tendentiousness is the immanent

traction that people procure on matters, often guided by what appears to be most

readily communicable, i.e. by what can cause people to find themselves able to

operate on the same page. It is important to note that operating on the same

page is not necessarily the same thing as understanding meanings. Garfinkel

always insisted that accounts were “vague” and that they were subject to

“indefinite elaboration” (the etcetera principle). Here we must recall

Garfinkel’s often repeated warning: “There is nothing hidden inside of our

heads but brains.” The world is there in front of us, in the spectacle

we are sharing, and that is why thinking is mostly a public activity. “Tendentious,”

which I believe is a term Garfinkel did not use until the 1980s, is a way to

repair our being too cognitivist in our studies. It is an appreciation that

things run along to wherever they are heading, on their own, and we mostly are

left to discover them after the fact. This is not to suggest that we never try

to bring our focus to bear upon events, it is only to observe that much of the

time we do not yet have a comprehensive grasp of what we are doing. To assist us in our efforts to examine the

intricacies of this peculiar situation, at once curious and unavoidable, I

offer the topic of what I am calling “Objectivation,” after Husserl (1969: 34;

1970: 358-61; 1973: 199), Schutz (1967: 133-34), and Garfinkel (2006: 135). Objectivation

is the work of turning our thinking or activities into objects that are

publicly available for people to use for organizing the local orderlinesses of

their affairs. These objects can be notions or they can be actual physical

objects, or both. They have a materiality that allows them to sit there in the

spectacle, permitting parties to use them as focal points for their

collaborative attention, i.e. for getting everyone on the same page so that

they can commence the work of making their affairs orderly. They are the basic tools

at hand with which the participants can work cooperatively. Most importantly, one of my

discoveries is that people do not “construct” or “produce” these objects;

rather, the objects find their way to centerstage on their own. Even when

people do try to plan for them, parties are surprised by what they end up

becoming, even though it is typical that parties will avoid displaying any

surprise. By working “on their own” I mean that they have a ubiquitous temporal

sequence that works like this: Account → Confirmation → Objectivation → Disengagement There is not the space here to offer a

detailed theoretical explanation of accounts.[4]

This is a longstanding topic in ethnomethodology, although it is not always

fully understood, and much has been written about it. Instead, I will take

advantage of the multimedia aspect of this journal and offer some demonstrations

of naturally occurring interaction that illustrate what accounts are and how

they work in local occasions. Accounts only come to be adopted when they

are confirmed by the parties who are present when the account is

uttered, and this phenomenon seems to be well understood. Objectivation is

equally important for the social work that parties face (that is, for the

“sociality,” to use the term suggested by Simmel), even though the topic has

not been given the same attention that accounts and confirmation have received.

According to Simmel (1959b: 337), our subjective impressions “become objects as

they are transformed into fixed regularities and into a consistent picture.” Objectivation

is part of the way that parties come to produce the social “facts” about which

Durkheim spoke and which is still considered to be one of the principal topics for

sociological research.[5]

This stage of this temporal sequence serves to point us toward objectivation as

a radical phenomenon, by which I mean the endless, in situ work of

parties to provide themselves with the tools necessary for organizing an

orderliness for their situation. Especially, the gloss “objectivation” is

intended to emphasize the communicative work of producing a Durkheimian thing. It

should not be allowed to stand in for a study of that work but should help to guide

the analyst to just where that work is taking place. Absent the identification

and scrutiny of this collaborative public work, in its specifics, this step of

the model is good for nothing. Ignore the model, but do look for the local work

of producing the public object that affords a cohort of persons a means for

coordinating their actions. Disengagement involves a degree of social

amnesia that is applied to what has been objectivated. It is the activity by

which parties are able to render themselves unaware that the “facts” they have

adopted emerged within (“inside-with”) social processes in which they just had

a hand. This amnesia is necessary for the objectivated tool, thing,

ethnomethod, result, etc. to possess the moral status that is required if it is

to compel conformity. Nevertheless, the apparent cohort independence of what is

objectivated usually depends upon provision of some acknowledgement or public

ratification of this elevated status; disengagement contributes to providing

for the independence of what has been objectivated and for the “immortal”

character of the social facts, as Durkheim described. It permits parties to

sustain the illusion that the reality, as they acknowledge it, has fallen out

of the sky (perhaps not simultaneously with the Ten Commandments but shortly

thereafter) without their intimate participation, in just the way that my grade-school

librarian always managed to do with her rules (giving me the opportunity to

make many early studies of this phenomenon). Three illustrations of the model: Utilizing the resources of this multimedia

forum, video clips of three diverse cases of naturally occurring social

interaction are presented in order to specify, by way of illustration, each of

the first three of the components of my model.[6]

These short “studies” include Play in a Game-with-Rules, Tibetan Philosophical Debating

at a Buddhist university, and an Espresso-Tasting Session guided by a master

roaster. 6.1 Play in a Game-with-Rules The first illustration involves the

formulation and objectivation of a rule of play during a game called Aggravation.

The players are four students who had never played the game before. They are

completing their reading of the rules and are about to commence play. The

rules, of course, are unable to cover everything, and in our clip the players

deliberate what to do about dice that accidentally roll off the table and onto

the floor: The player on the

right (Player D) observes that the player who is rolling the die is shaking and

rolling the die with considerable energy, so she raises the matter of what to

do if the die should roll off the table. This is important because it can

happen that a player who likes the number on the die will accept that number as

the roll, but may try to re-roll if that number is not to the player’s liking. To

Player D’s question, the player second from the left (Player B) offers a

tentative assertion that carries the implication that if it is offensive there

should be a policy for handling the situation. Player D commences an account,

to the effect that such a person should be required to re-roll the die, and

Player B quickly (in fact, almost simultaneously) confirms that account.

Player B adds an observation that such a policy is in fact a rule made up by

themselves, to which the female player next to him (Player C) chuckles, implying

cooperation. Player A at the far left, the potentially offending player, comments

upon what has transpired by jesting that the policy has become a “house rule,” at

which Player C laughs. The transcript picks up the interaction from 0.19

seconds, approximately halfway through the clip: A “house rule” is more common in

cardplaying than it is in boardgame playing, and it is a rule that is not

included in the formal rules or rulebook but is required by what Garfinkel

(1974) has called the game-furnished conditions and is adopted by the casino or

house at which the game of cards is being played. It more or less enjoys the

same status as a rule in a rulebook or instructions. While in this clip it is

an artful jest, a bit of humor that contributes to the players’ enjoyment of

the play, it also is a move that effectively objectivates the policy so

that it stands as a fact of their play beyond the reach of any individual

player. This had consequences for their play later when a player who attempted

to move the piece in conformity with the number on a die that had rolled onto

the floor was overruled by this objectivated policy. 6.2 Tibetan Philosophical Debating The debating

is in Tibetan, and viewers will need to consult the transcript of the

interaction for the English; the transcript can be coordinated with the video

by consulting the timings. In what is typical for these Tibetan dialectics, the

account provided by the debater who is standing is offered first in a positive

form, then in a negative form, and once again in a positive and conclusive

form. This repetition is used for multiple reasons: to make the issues at stake

readily visible and hearable for everyone who is present, to possibly catch the

Defender in an error or a confusion, and to contribute to setting a rhythm or

pacing for their live dialectics. In this clip, the defenders confirm both

positive accounts and disconfirm the negative form of the account: … In order for the parties to promote the

result of their philosophical collaboration to the level of a social fact, not

only do they need to provide a public account and secure confirmation

for it, that account must be objectivated; that is, it must be turned

into a social object that is able to stand in front of the parties

independently of their talk. There are many practices that co-participants use

to achieve objectivation. The debaters here use a different practice for

objectivating the account than the ones found in our Game-with-Rules

illustration, but it accomplishes the same purpose. In this case the confirmed

account is objectivated by Defender 2’s assertion that “We say …,” which places

the facticity of the matter out of the hands of any of the individual actors, and

also by the Challenger’s rhythmical repetition of the account (which is much the

way an auctioneer will accomplish it). It becomes a fact-in-hand, from which the

parties will be able to proceed securely. This too conforms with our temporal model: Account → Confirmation → Objectivation With their “intersubjective thought object” (Schutz 1971: 12) in hand and “given equally to all” (Schutz 1967: 32), these Tibetan debaters can

proceed with a course of rigorous philosophical dialectics. 6.3 Espresso-Tasting Session The third illustration of the model is

extracted from a Coffee-Tasting Session in Italy guided by a master roaster, and

the parties are speaking Italian; an English translation is included with the

transcript. These lay tasters are offering their assessments of the flavors

they find in the espresso blends they are sampling. They are not doing blind

tasting, since these tasters collaborate about each flavor descriptor, and also

because their assessments are being subjected to review by the master roaster

who has designed blends of several coffees, and roasted and prepared them

according to a certain plan of his own. The parties still need to coordinate

what they will accept to be facts, which they do in the manner of our model, but

this is an occasion where claimed expertise does play a role in directing the

discussion: This illustration presents us with yet

another practice for objectivating an account. Although at first there was some

contestation on the part of C, the tasters confirm the appropriateness

of “dark chocolate” as a proper account for the taste, and that account

is expanded by the taste descriptor “peanuts.” The master roaster (C) combines

those two descriptors into the single descriptor “an oily seed,” and when his

summary account receives confirmation, C consolidates the authority of that

descriptor by objectivating it, which he accomplishes by giving it a universal

name (“the Italian extraction”) that suggests

widespread knowledge about it along with general acceptance of its veracity as

a definitive account. Following this, none of our tasters who wishes to appear

competent will contest that taste descriptor, and so it stands as a new fact of

life in the parties’ work of sensory evaluation. Although in each of our illustrations the parties employ

a different practice of objectivation, all three cases conform to the suggested

progressive sequence: Account → Confirmation → Objectivation Let me be clear about how I am treating this model:

these events surely do not take place just because I have developed a model.

And in the spirit of Garfinkel, I beg the reader not to pay too much attention

to it, for the reason that it can blind one to the radical events that are

going on and diminish the openness of any examination. Under no circumstances

should these stages be substituted for the concrete identification,

observation, and specification of the constituent activities. Even so, my

students in ethnomethodology have found this temporal description helpful for guiding

their inquiries regarding some of the more interesting aspects of ordinary

sociation. While much attention has been paid in the ethnomethodological literature

to accounts and to confirmation, less attention has been given to objectivation

practices, even though they are critical for the establishment of social facts.

The point of this exercise is to remedy this lacuna. In his studies of accounts and “formulations,”

Garfinkel observed that accounts require confirmation by others, and that any

formulation of local affairs was always “subject to review by others.” Accounts

are the corporate means by which candidate understandings become public objects.

Objectivating something, which means to construct a unity for it so that

it can be shared, retained, and communicated, is a topic that Edmund Husserl persisted

in examining from the period of Logical Investigations, in 1899, until

his final lectures in 1936, including “The Origin of Geometry.” In “The Origin

of Geometry,” Husserl (1970: 360) emphasized the importance of how concepts are

objectivated in the social world: “In the unity of communication among several

persons, the repeatedly produced structure becomes an object of consciousness,

not as a likeness, but as the one structure common to all.” For Alfred Schutz this objectivation

was key to his tracking of intersubjectivity, and he explained that it involves

the public work by which something is given equally to all. According to Schutz

(1971: 12) an intersubjective thought object is formulated by and for the

parties in order to facilitate the work of their sociality, and this was an

early clue for Garfinkel. For Schutz, who was the first to speak of production

in this way, the “objective meaning” refers to “the already constituted

meaning-context of the thing produced whose actual production we meanwhile

disregard” (Schutz 1967: 133-34). This “disregard” is the social amnesia, the

disengagement. One of Garfinkel’s discoveries was that parties are not

motivated by the meaning of an account as much as they are motivated by the

demand that they render their local affairs orderly. One way by which people learn just-what

they mean is to objectivate their notion and then observe what that

objectivated notion accomplishes, that is, just-what it comes to mean during

the course of their interaction. Once some understanding is discovered, that

is, as something begins to be played out in local affairs in a way that is

evident, that understanding can be displayed to everyone who is present,

and in that way an understanding can be made an objective fact that stands

independently of the people who staff the course of affairs. In the technical words

of Husserl, which were adopted and extended by Garfinkel, parties gradually

work to substitute “objective expressions” for “essentially subjective and

occasional expressions,” and this is work that is done collaboratively. Husserl did not investigate

extensively the local contingencies of this substitution, and Garfinkel (2002:

204-5) took that up as a principal topic for ethnomethodological research. In

undertaking these studies, Garfinkel and his students discovered something

fantastic: this local work can include situations where words, glosses, and

categories exist as objects for everyone before their practical

intelligibility is fixed. In fact, using the glosses in order to fix

their sense and reference is part of the work that a local cohort of actors

routinely performs when organizing the objective intelligibility of an

occasion. The part that is fascinating about this, and the part that is arational

about it (and here I do not mean non-rational, for the reason that rationality

can consist of precisely this), is that agreements can occur before people

understand just what they mean; but despite the blind into which a cohort is

willing to enter headfirst, from the outset the confirmed and objectivated account

is binding upon everyone, even before its sense and reference has been

fully determined. Let me specify this, using another example that involves lay

coffee tasters: “Bold” A It’s

definitely bold. B It’s

a very bold coffee. A I

definitely agree with the boldness … A It

was really sour, bitter, too strong. But bold. Interviewer:

What do you mean by “bold”? A He

was the one that said “bold.” How is bold? Here the first taster offers the original, albeit indeterminate

taste descriptor of “bold.” Possibly his immanent preoccupation was with

getting through the task without appearing dumb, but he did closely attend to

the coffee before offering his descriptor, a descriptor with which Taster B

agrees. Taster B’s agreement leads Taster A to double-down on his account. But

then the interviewer asks Taster A to explain to her just what this descriptor

means. At this, Taster A pretends that he was not the one who proposed the

descriptor. His gambit makes it evident that he did not possess a clear

understanding of the meaning of his descriptor. Since probably Taster B also lacked

a clear understanding about just what was intended by the account he was

confirming, when the two tasters consolidated their affirmation of the

descriptor, they were validating an account that lacked specific content. In my

coffee-tasting data, specification of such content is a matter that is sometimes

left to subsequent tasting and discussion. In this case the Interviewer’s

question exposes the vacuity of the tasters’ formulation of the coffee’s flavor.

In Taster A’s defense it should be observed that according to the way that

social facts are produced, and to how accounts are objectivated, the propriety

of an account is very much the result of a collaboration among the parties, and

so it might be said that Taster B had as much to do with the objectivation of

the account as did Taster A. What is vital for the success of the interaction

is that the parties provide some order to their assessment and are able to operate

on the same page. Their adoption of an account before it acquired its content

was how they accomplished that. Here is another instance of persons

who agree with a formulation before they know what it means. It comes from my

data on games-with-rules: "Okay" Bill:

[Reading rules] “You may trade resources with other players for using

maritime trade.” Linda: Okay. Bill: Which we don’t know what

that is. Linda: ’Kay. Bill:

[Summarizing rules] You may build roads, settlements, or cities. And/or buy

development cards. You may also play one development card any time during your

turn. After you’re done, pass the dice to your left, who then continues the

game by repeating what we just did. Linda: So

I can like roll and get settlement cards or I mean like resource cards and then

I can like do stuff? Bill: Yep. In the case of this interaction, which

depicts gameplayers collaborating in the task of working out what the rules for

gameplay are supposed to mean, we know that they have agreed upon a gloss for

some gameplay without knowing what they have agreed to because one of the

parties observes publicly, “We don’t know what that is.” This does not deter the parties from

continuing to review the rules in such a manner. It is common for parties to

read rules that are not intelligible; in fact, when the reading is divorced

from some gameplay, rules frequently are not intelligible, and so it is rare

for gameplayers to read all the rules of a game before they commence play. Too

much reading of unintelligible material can render a local social interaction

absurd. For this reason, Linda offers her gratuitous cooperation, and that is

not an unimportant step in allowing the parties to proceed with organizing

their understanding, but that understanding lies ahead of them in the

interaction and so is part of what Schutz and Garfinkel have called the

prospective and retrospective sense of understanding, which has played an

important role in ethnomethodological analyses. Bill’s “Yep” in the final line

of the transcript is probably gratuitous as well. John Heritage and Geoffrey

Raymond (2005: 15) suggest, “Within the general framework of agreement on a

state of affairs, the matter of the terms of agreement can remain,” and

Heritage (2013: 383) tells us, “In the midst of agreeing with one another,

speakers are still addressing the terms of agreement.” Heritage and

Raymond emphasize there can be a “raw affiliation” (2005: 17) that lacks any content

and amounts to merely “a simulacrum of agreement.” These raw affiliations are

fascinating and deserve further study because they help to reveal the brute

sociality of our lives. Even though an agreement lacks

content and does not yet mean very much, that the local cohort has already

accepted an account serves to assist the account in winning the moral authority

of a social fact in the way that Durkheim has elaborated. In fact, all three

stages of our model can be fulfilled without there being much content behind

the material expression of an account. A good deal of what makes conversations

interesting, even exciting, is that the meaning of an interaction is often left

unresolved, presenting participants with the highly engaging task of resolving

matters, at least for practical purposes. Here I am not at all speaking about

how individual understandings get “negotiated.” More commonly, no one knows

what is going on, and parties discover only serendipitously, inside-with the

emerging affairs, some way to get on the same page. And it does not necessarily

have to really be the same page, it can be that the parties only think it is

the same page. Situations like that are hardly rare. It is possible to become

capable of better recognizing them when we abandon our practice of believing

our own social mythologizing; however, there are practical benefits in

organizing the local orderliness of some social interaction by working out a structure

and using it to coordinate the interaction before the participants themselves

have recognized the meaning and consequences of what they have accomplished. In

fact, it is difficult to imagine social life without this. 7.1 Anonymity and moral compliance The immortality of social facts was an orientation Durkheim

developed by considering Montaigne, who spoke of the mystical authority of the

law. What are the origins of this “mystical authority”? To some extent it must be

rooted in a sense of responsibility for others’ expectations; but why is there

a sense of responsibility for other’s expectations? Here we discover a second

sense of “accountability.” The first sense of accountability is how the intelligibility

of emerging affairs can be summarized in an account, as I have been describing,

and the second sense of the term is how we can be oriented to the expectations

of others and so are “accountable” to others for affirmation of the

appropriateness of our behavior. Commonly, others’ expectation is that we will be

cooperative, and this is an expectation that can be easily read on the face of the

other. Moreover, in many circumstances our very first objective is to stay out

of trouble and we are eager to be cooperative, even though we may not yet know

what it is we need to do in order to be cooperative. Garfinkel (1967: 35) begins his

“Studies of the Routine Grounds of Everyday Activities” – which remains the

name for our “studies” even today – by discussing Kant, for whom there were two

“mysteries,” the stars in the heavens and the moral order within: “For Kant the

moral order ‘within’ was an awesome mystery; for sociologists the moral order

‘without’ is a technical mystery.” Here we are examining this moral order “without,”

and the responsibility about which I am speaking is anonymous. That is

to say, it is any member’s practice. Let’s have a closer look at it. "Devo dire?" A Here Italian lay tasters are doing their

best to comply with the protocols of proper coffee-tasting, but they are

handicapped by the fact that they do not really know what those protocols are.

They were given a form on which to note some taste descriptors and to offer a

few numerical evaluations of some categories of flavor. Taster A commences her

summary by reading off her sheet: A Allora, io he escrito, va ben,

amaro. E noce especiato, ho cerchiato, però poi ho scritto “poco corposo.” Here she pauses in order to read how her contribution

is being received by the others, and she pays particular attention to the young

bearded man at the end of the table who is facing her (see clip) and who is the

organizer for the tasting session. Gazes like this are opportunities for

parties to solicit what their account has come to mean and also for

monitoring their satisfactory compliance with what is expected. In this way her

gaze services both senses of the term “account.” She hesitates here because she

is uncertain about just what she is supposed to do next. So she asks of the

session organizer, “Am I supposed to say the numbers too?”: "Devo dire?" B A Devo dire anche i

numeretti? B Si, se vuoi si. A Va ben. Aroma 6,

corposità 3, equilibrio 5, dolcezza 5, vellutato 3, e retrogusto 7. What is noteworthy about this this clip is that B, the organizer of the

session, does not really have a preference regarding how A reports her sensory

evaluation. In fact, he is deferring to her even as she is deferring to him (note

particularly B’s facial gestures at second 0.04 in the “Devo dire?” B

Clip). Such an “After you, Alphonse” / “No, after you” routine is a comedy that

is common in our interactional affairs. Taster A is ready and willing to comply

with any rules that are in force; her problem is that she does not yet know what

those rules are. In this clip the situation is even worse than this, since no

rules have been established. The openness of the structure for interacting can sometimes

become paralyzing, so A proceeds with one way to accomplish her reporting,

which, by the time the other tasters take their turns, becomes the authorized

way to do it, presenting us with one more case of an event organizing itself. What

is occurring is that each participant is attempting to locate a local structure,

and the parties’ desire in general for a structure, any structure, is more

important than the particular structure that they adopt. Such a situation is responsible

for many follies in our everyday lives. For instance, a first person can

suggest an account, and that account can elicit a confirmation by a second

person; however, it can (and does) happen that a second person misunderstands

the meaning of the account given by the first person and so confirms something that

the first person did not intend. It can also happen that the first person will

decide not to correct the second person, even when the first person recognizes

that the account has been misunderstood (cf. Liberman 2017: 171-215). How can

this happen? One way it can happen is that a third person, who does not

understand the sense or reference of the account but who does recognize that

the first person and the second person are in agreement about it, will nod his

or her head and confirm the account gratuitously. It could be that the first

person may have been ready to correct the second person until the third person

offers the additional gratuitous confirmation. The additional confirmation can

cause the first person to choose to remain silent, first because the immanent

local work of undoing a confirmed or objectivated structure can become a

complicated matter, and second because it appears that a satisfactory communal

agreement has been reached and there may be some reluctance to disrupt an

established harmony, even when the harmony is only apparent. It is possible

that the first person thinks that the second and third persons understand what

they have agreed about. All of the parties (including a fourth party who

remains silent, and confused) can even act on the basis of an account confirmed

this way. For the sake of giving some flesh to our example, let us say that the

topic was about the group going to a movie, and the first person suggests a

currently playing movie that stars Denzel Washington, who is presently starring

in two movies; the second person thinks only of the current movie that was not the

one that the first person had intended. In the way described, the four of them can

head off to watch a movie that none of them had a desire to see. Moreover,

that no one wanted to see the movie can remain opaque to each of the parties.

There is no way that social scientists could gauge how many decisions are set

into motion in just such a fashion, so intricate is the interaction. What I am

describing is ubiquitous, and it can involve a matter as simple as when parties

laugh together heartily without knowing what it is they are laughing about. The responsibility that people

feel to comply with others’ expectations operates in the midst of the

objectivation practices. In

the transition from the article, “Studies of the Routine Grounds of Everyday

Activities” that appeared in Social Problems in 1964, to the second chapter

by the same name of his 1967 Studies in Ethnomethodology, Garfinkel

omitted the first paragraph of his “Concluding Remarks,” which read, “The

expectancies that make up the attitude of everyday life are constitutive of the

institutionalized common understandings of the practical everyday

organization…” (Garfinkel 1964: 249). Part of the motive for objectivating accounts or institutionalizing

common understandings is that any compliance with what is expected needs to be

organized, and what behavior it is that can constitute correct compliance must

be something that everyone present is able to recognize, since this knowledge

must become a public possession. Moreover, when people act in compliance they do

not act as individual actors but as sort of a local “anyone,” as an anonymous

“member.” Accordingly, part of the local work of parties is to provide for the public

recognizability of the methods and agreements that are set into play. The work

of making them recognizable (that is, “instructably observable and instructably

reproducible” (Garfinkel 2002: 148)) is collective, and such work is not

usually undertaken on one’s personal behalf but is done anonymously. I have observed that each party

is preoccupied with figuring out what must be done “next” before the time to do

it arrives. Since events can move very fast (there are no “timeouts”), strange

things can happen. These strange things can become an embarrassment for social

scientists who take their “Just So Stories” seriously. My argument here is that

we need to abandon some of the social mythologies of rules,

laws, negotiated agreements, etc., which render our lives more deliberate

and rational than they in fact are,[7]

and pay closer attention to the granular details of social interaction

turn-by-turn and move-by-move. Let us learn from the real world of which we

speak. Surely this aspiration is a

component of what comprises the study of “sociality” that Simmel recommended. Simmel

(1959: 328) writes, “Perhaps this sort of insight will do for social science

what the beginnings of microscopy did for the science of organic life.” I

certainly hope so. Indeed, the fine-grained, turn-by-turn analyses of

ethnomethodology involve just this kind of microscopy. Attewell, P. (1974)

“Ethnomethodology Since Garfinkel.” In Theory and Society 1: 179-210. Daston, Lorraine, and Peter

Galison 2010 Objectivity. NY: Zone Books. Cicourel, A. (1974) Cognitive Sociology: Language and Meaning

in Social Interaction Garfinkel, H. (1964) “Studies of the Routine Grounds of Everyday Activities.” In Social Problems 11:

225-250. Garfinkel, H. (1967)

Studies in Ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, MJ: Prentice-Hall. Garfinkel, H. (1974)

Soc 149 Class Lectures given at UCLA’s Department of Sociology. Garfinkel, H. (2006)

Seeing Sociologically: The Routine Grounds of Social Action. Boulder,

Colorado: Paradigm Publishers. Gurwitsch,

A.

(1966)

Studies in Phenomenology and Psychology, Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern

University Press. Heidegger, M. (1962)

Being and Time. Trans. by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson. NY:

Harper & Row. Heritage, J. &

Raymond, G. (2005)

“The Terms of Agreement: Epistemic Authority and Subordination in

Talk-in-Interaction.” In Social Psychology Quarterly 68 (1):15-38. Heritage, J. (2013)

“Epistemics in Conversation.” In The Handbook of Conversation Analysis,

eds. Jack Sidnell and Tanya Stivers. Oxford: Blackwell. Husserl,

E.

(1962)

Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology. London:

Collier-Macmillan. Husserl, E.

(1969)

Formal and Transcendental Logic. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. Husserl, E.

(1970)

“The Origin of Geometry,” Appendix I in Edmund Husserl, The Crisis of the

European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology. Evanston, Ill.:

Northwestern University Press. Husserl,

E.

(1973)

Experience and Judgment. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press. Liberman,

K. (2004)

Dialectical Practice in

Tibetan Philosophical Culture. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. Liberman,

K. (2013)

More Studies in

Ethnomethodology. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. Liberman,

K. (2017) Understanding Interaction in

Central Australia: An Ethnomethodological Study of Australian Aboriginal People Macbeth,

D. (2011)

“Understanding Understanding as an Instructional Matter. Journal of

Pragmatics43 (2): 438-451.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962)

Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge. Moerman,

M. & Sacks, H. (1988)

“On ‘Understanding’ in the Analysis of Natural Conversation.” In Moerman, Talking

Culture, Ethnography and Conversation Analysis. Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press, pp. 180-86. Proust, M. (2002)

Finding Time Again. London: Penguin

Books. Psathas, G. (2004)

“The Correspondence of Alfred Schutz and Harold Garfinkel.” In H. Nasu, L. Embree, G. Psathas and I. Srubar (eds.), Alfred

Schutz and His Intellectual Partners. Konstanz: UVK Verlagsgesselschaft

mbH, pp. 401-434. Schutz,

A.

(1967)

Phenomenology of the Social World. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern

University Press. Schutz,

A.

(1971)

Collected Papers, Vol. I. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. Simmel, G. (1959a)

“The Problem of Sociology,” in Essays on Sociology, Philosophy and

Aesthetics. NY: Harper & Row, pp. 310-36. Simmel, G. (1959a)

“How Is Society Possible?” in Essays on Sociology, Philosophy and Aesthetics.

NY: Harper & Row, pp. 337-56. [1] This paper is

based upon a plenary address delivered at the 12th Conference of the

International Institute for Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis

(IIEMCA), held at the University of Southern Denmark in August of 2015. Two

earlier and primitive versions of that address were given, one in 2014 as the

keynote at the Annual

‘BrainFood’ Conference, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark, under

the title “Some Arational Bases of Rational Activities;” and the other as a talk in 2015 to the Facoltà di

Sociologia at the Università di Trento and published in their departmental

papers (“Studying

Objectivation Practices,” in Quaderni del Dipartimento di Sociologia e Ricerca Sociale, Università di Trento,

Italy, New Series (Electronic), No. 2, 2016, pp. 1-22). [2] By major or macro social

forms Simmel (1959: 326-27) is referring to “superindividual

structures”: “Great organs and systems like states, labor unions, priesthoods,

family forms, economic systems, military organizations, guilds, communities,

class formations, and industrial divisions of labor, seem to constitute society

and therefore appear to be the subject matter of the science of society.” [3] “The Boston Seminar,” 6/24/75. This is available

online at the EMCA-Legacy website (http://emca-legacy.info/garfinkel.html). [4] Chapter 5 of Ethnomethodology’s

Program (Garfinkel 2002: 169-93) is as good a place to begin as any other. [5] An initial

explanation, along with a case study, is available in Liberman 2004: 92-106. [6] The fourth

component, Disengagement, awaits fuller specification. [7] For a brief

expansion of this ethnomethodological perspective on rules, visit “Le Regole di

Surf: Intervista a Kenneth Liberman SurfinSalento.it,” available at times

31:34-35:00 (the only portion of the interview that is in English) on the video

that is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WpOjNm4AbTw&feature=youtu.be

OK.

… “Velvet texture”? …

4. Excursus: Some historical perspective

5. Congregational work

6. Objectivation

D:

What do we do if the die rolls on the floor?

B:

Well if it’s offensive.

D:

/Re- //Re-roll

-Account

B:

/ // Re-roll.

-Confirmation

C:

Hah.-

A:

House rule of Aggravation.

-Objectivation

C:

[Laughs while gazing at D.]

Challenger

The reflection of a face in the mirror in the continuum of

an ordinary person is posited by the mind as erroneous.

-Account

Defender-1:

It is. It is.

-Confirmation

Challenger:

It does not follow that the lack of accord between the

appearance of the reflection of the face in the mirror and its mode of being is posited. [Hand-clap]

9:04:53

-Negative-of-

-Account

Defender-2:

CHEE-CHEER [lit. “Because of what?” = No]

-Disconfirmation

Challenger:

So, the lack of accord between the appearance of

the reflection of the face in the mirror and its mode of being is posited. [Hand-clap]

9:04:55

-Repeat-of-

-Account

Defender-2:

Yes.

-Confirmation

Challenger:

It follows that the mind that has posited

the lack of accord between the appearance of

the reflection of the face in the mirror and

its mode of being is not complete, according to the Middle Way. [Hand-clap]

9:04:59

-Extension of

-Account

Defender-2:

We say it is not complete.

-Objectivation

A

Cioccolato /fondente

Dark chocolate

-Account

B

/Cioccolato

Chocolate

-Confirmation

C

Mm.

D