2018 VOL. 1, Issue 1

ISSN: 2446-3620

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7146/si.v1i1.105499

Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

LEARNING TO SAY GRACE

Tim Greer[1]

Kobe University

Abstract

Based on a detailed analysis of four naturally occurring dinner-table conversations video-recorded over a period of three weeks, this study uses longitudinal Conversation Analysis to track an outsider's growing involvement in the family ritual of praying before each meal. Through a detailed turn-by-turn account, the analysis demonstrates how the visitor moves from peripheral observation to more active participation, suggesting that his involvement in learning to say grace was one way he adapted his interactional and cultural practices to align with those of the host family. The analysis also considers the role of other family members in inviting participation and reprimanding non-normative behaviour.

Keywords: interactional competence, development, homestay, mundane L2 talk, prayer, learning in the wild

1 Pre-meal prayer as a speech event

Praying before eating is a common practice in many religions and cultures around the world and typically involves giving thanks for the meal and blessing the food. In English-speaking Christian cultures, this prayer is usually known as saying grace or giving the blessing. While some families recite the same short grace each time, others formulate the prayer differently on each occasion by taking into account the audience and context. Other families do not say grace at all or do so only on special occasions.

Interactionally speaking, the grace becomes part of the opening to the meal, signifying that the meal has begun, and the participants are allowed to eat. Ochs and Shohet (2006) note that grace is also one way in which adults culturally structure the socialization of children into mealtime interaction, while Capps and Ochs (2002, p. 45) point out that such socialization involves practices of readiness and maintenance of the appropriate “kinesic and linguistic inflections of prayer,” such as closing one’s eyes, refraining from eating, and closing the grace with the word ‘Amen’.

Children are therefore socialized into the family practices of grace, but how does this socialization take place among adult novices to the host culture? This study uses longitudinal conversation analysis to track one Japanese homestay student's acculturation into the cultural ritual of saying grace as it is practiced by his host family, an immigrant Mexican family living in Australia. Based on a detailed analysis of four video-recorded dinner table conversations, the study demonstrates how the homestay student moves from peripheral observer to a more active participant in this cultural ritual. The analysis also considers the roles of other family members, including the socialization of a child who is a relative novice to the practice, and the family's accommodation of the Japanese visitor into its daily mealtime routines.

2 Longitudinal conversation analysis

Recent years have seen a growing interest in longitudinal Conversation Analytic studies, particularly those in which evidence for the development of interactional competence is established by comparing sequences of interaction over an extended period of time (e.g., Greer, 2016, 2017; Brouwer & Wagner, 2004; Hall, Hellermann, & Doehler, 2011; Hellermann, 2007; Ishida, 2009; Lee & Hellermann, 2014; Markee, 2008; Nguyen, 2012). However, such research also presents epistemological challenges, including the question of whether changes in an interactional practice are due to a participant's developing competence or changes in the local context (Hall & Doehler, 2011). This study adopts the viewpoint that interactional competence is co-constructed, and thus any developments must be understood not only as changes in the behaviours and practices of the novice learners, but also as changes among the entire group of participants. It is not just that a learner gets better at understanding and delivering a given action, phrase, or turn design; those around the learner also become aware of the learner's developing competence and therefore deliver future iterations of the practice in ways that treat the novice as increasingly competent. The analysis in the current study thus concerns both the novice language learner and the host family, who are positioned as relative experts with regard to the English language. The family’s recognition of the learner's growing competence with regard to the cultural practice of saying grace becomes publicly available through the interaction in the final video when they ask him to say the prayer.

3 Background to the data

The data come from a series of dinnertime conversations that were recorded in a house in Brisbane, Australia in February and March 2015. Although he is by no means the most active speaker, the focal participant is Ryo, a 19-year-old university student from Japan, who was taking part in a three-week study abroad tour at an Australian university. The homestay hosts are immigrants from Mexico who speak both Spanish and English in the home. The family consists of Mum, Dad, and their two sons Axel (11) and Luis (6). In the first recording, there are also two visitors, Grandma and Dad’s brother, Juan.

The family is Christian and active in their local church. They begin each meal with a prayer that appears to follow a set structure, although it is not delivered in exactly the same words each time. In the first two recordings, it is Dad who says grace, in the third video Luis says it, and in the fourth and final recording Ryo is asked to deliver the prayer. This permits comparison of how these two relative novices accomplish this speech event. The analysis begins by examining how Dad performs the grace on the first two occasions, in which Ryo is still new to the family and therefore very much an observer with regard to this cultural practice.

Ryo is a Buddhist and does not usually begin his meals by praying. In Japan, however, people do customarily begin a meal by saying itadakimasu (“I humbly receive”), though this is generally directed toward the food preparer/provider (and by extension, the farmer who produced the ingredients) rather than any particular deity. Ryo does, however, have some general knowledge of Christian customs. He went to a Christian kindergarten as a child, and although he does not know the prayer that Dad recites, he is able to recognize its ending and produce a timely “Amen”, to signify that he recognizes the prayer has ended.

The transcripts are based on the conventions developed by Mondada (2012), with the onset and completion of embodied action by each participant denoted relative to the talk with the following symbols:

Ryo |

Mum {

Dad ^

Axel *

Luis ◊

Juan ‡

Figure 1. The family seating arrangement during the T2 recording

The dataset is part of a more extensive corpus of homestay dinner table conversation, but this section consists of four conversations of approximately 20 minutes each, recorded on four occasions and totaling approximately 1hr 18min.

4 Analysis

The remainder of this paper tracks the openings of each of the four meals in order to examine how Ryo becomes increasingly familiar with the grace ritual. By the third week, Ryo is asked to say the prayer for the family, and this provides evidence of his understanding of how this interactional practice should normatively take place.

4.1 Observing a violation of the practice

We begin with the opening of the first meal, which took place on Ryo’s third evening in Australia. Although he does not play a central role in the grace, Ryo is watching and observing. Of particular interest here is how the younger brother, Luis, is reprimanded for not maintaining an appropriately respectful stance throughout the prayer.

Video 1. T1, Tuesday, 24 February.

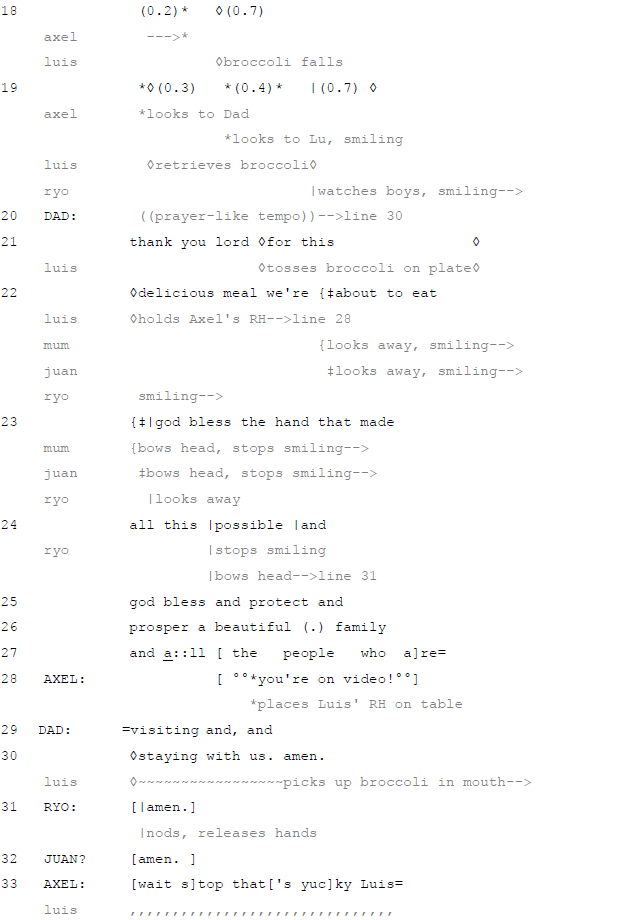

Excerpt 1. T1, Tuesday, 24 February

Gif 1

Gif 1

Gif 2

Gif 2

The grace itself is an opening to the meal, but in order to begin the prayer, there must be a pre-expansion (Schegloff, 2007 , p. 28) to establish the necessary conditions that allow the grace to commence. In this instance, those conditions involve Juan, Ryo, and Axel setting the video camera (lines 1-2) and Dad checking that everyone is ready (lines 3, 7, and 9). Once the family members have physically aligned themselves in an appropriately respectful manner, in lines 7-9 Dad initiates a pre-grace expression of appreciation to those who prepared the meal. Since it is directed at co-present members rather than a deity, this is not hearable as part of the prayer proper; however, it does have some similar qualities, such as giving thanks, recognition, and respect, and the family treats it as an unremarkable part of their pre-grace routine. However, the younger son, Luis, does not immediately take up this respectful pose, leading to an incident in which he drops some broccoli onto his chair (lines 14-22).

Gif 3. Luis drops some broccoli just prior to the prayer

Gif 3 shows the moments just prior to the start of the prayer, in which Dad is calling the group together. The family generally complies by joining hands and adopting a somber stance, but the broccoli in Luis’ hand prevents him from taking hold of Axel’s hand properly, and this eventually leads to the broccoli falling onto Luis' chair. Of interest here is not the behaviour per se, but the way in which the three adults observe it. Mum, Ryo, and Juan are all watching the broccoli incident unfold (lines 14-23), and at this point in the talk their gaze direction could be seen as a potential warning to the boys. They are not openly smiling, though when the broccoli falls, it does seem that Mum and Juan are holding in a smile (line 22). Ryo on the other hand does not refrain from smiling at all—he gives a big grin while looking directly at the boys. As Dad has started to pray, in line 23, Mum and Juan turn away from the boys, adopting a suitably reverent pose, but Ryo maintains his gaze and smiles with his eyes open for just a moment longer, perhaps indicating that he does not realise the grace has started, or that he is expecting further acknowledgement of the misdemeanor. In short, Ryo’s timing is just a little slower than that of Mum and Juan, indicating that it takes him a little longer to judge the situation. As an adult, he does not join in the childish antics of Luis and Axel, but as an outsider to this community, we can see him still feeling his way forward with respect to the timing of this interactional event.

Dad signals the end of the prayer with “amen” (line 30), and Ryo repeats this, displaying his understanding that the prayer is over (line 31). Although Axel does not say amen, he does tacitly acknowledge the end of the grace by returning to his normal volume in line 33 and rebuking Luis for his behaviour during the prayer. As an observer of this admonishing, Ryo has experienced one way in which the routine expectations have been violated and how both public and tacit reactions to that play out. Axel’s rebukes are swift and straight, but the other adults have seen them and ignored them.

In the post-prayer slot and in overlap with Axel’s admonishment, in line 42 Mum chooses to direct her attention instead to Ryo, thanking him for his help and complimenting him on his efforts. Ryo acknowledges this and responds with his own positive self-assessment “I’m happy” (line 44). This sequence seems to signal the transition back to non-prayer talk by personalizing the sort of message that has just been delivered more formally and more routinely during the grace itself. Although Mum never says the grace in these recordings, she does deliver this sort of post-grace compliment, and in this instance she seems to be using them to avert, or at least ignore, any conflict that might be brewing between the brothers. From Ryo’s perspective though, he has witnessed ways in which a respectful attitude is both preserved and violated, as well as the consequences of the latter. In other words, he has been afforded an opportunity for socialization as a peripheral observer.

4.2 An expert formulation of the prayer

My analysis of the second excerpt focuses on how Dad formulates the grace, addressing part of the blessing specifically to Ryo. Dad's prayer here and in Excerpt 1 provide a baseline of what can be considered the normative practice for delivering the prayer in this family, both for us as analysts and for Ryo in real-time. In Excerpt 4, we will compare this with the way in which Ryo formulates his version of the grace.

Video 2. T2, 2 March

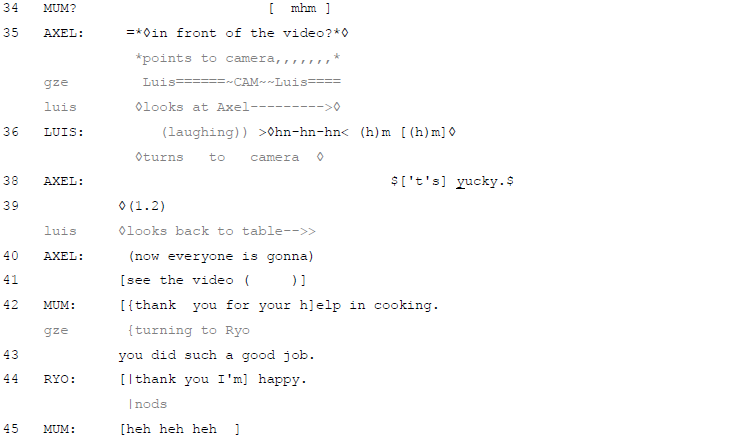

Excerpt 2. T2, 2 March

Pre-meal prayers are often routinized, taking the same form from day to day, although in some families they can also be totally unscripted. In this case, it seems that Dad uses a base prayer but ad libs it somewhat by formulating it for this particular audience. He begins in line 19 by thanking God for the food and seeking blessings for the family. The speed of his talk and the prayer-like tempo in which it is delivered help set the grace apart from the surrounding talk, and this adds to the impression that this is a regular routine or ritual. We will return to this point in Excerpt 4.

After saying “and prosper beautiful family” in line 25, Dad adds another incremental clause that is physically and hearably directed to Ryo: “and for homestay student family as well” (lines 26-28). While affiliative, this formulation locates Ryo outside the family membership categorization device. Dad ends the prayer with Amen then looks pointedly at Ryo, and there is a brief gap of 1 second in line 39, where it seems Dad could be waiting for some sort of response or acknowledgement from Ryo. However, Ryo's acknowledgement is minimal and does not go beyond the brief nod in line 29, and Mum goes on to transition back to mundane talk, explaining how to eat the dish before them (line 34). This may suggest one aspect of Ryo’s interactional competence that is not fully developed at this stage—the ability to acknowledge the sentiment expressed in the blessing in a timely manner.

4.3 A novice formulation of the prayer

In the third video, Dad selects Luis, the younger brother, to say the grace. The prayer that Luis says is inappropriately short, and this does not go unnoticed in the pursuant talk, leading to an opportunity for socialization for Luis and by extension for Ryo.

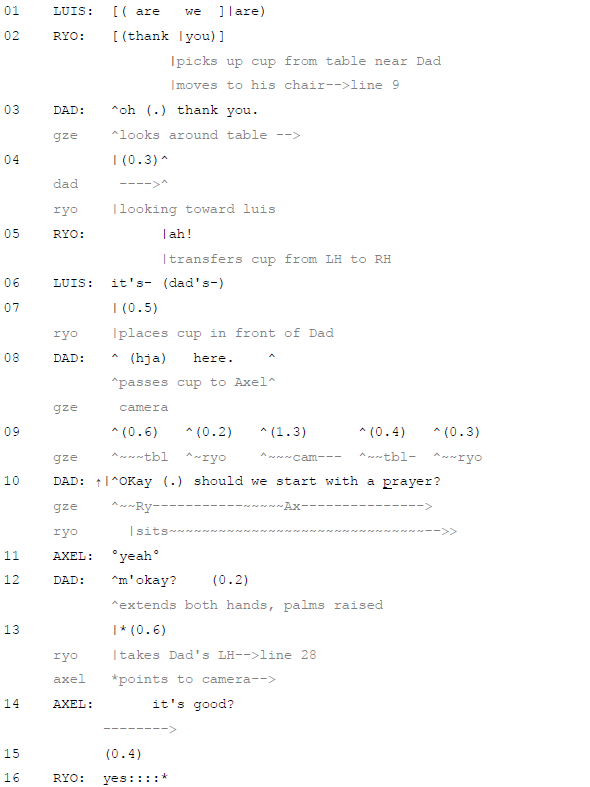

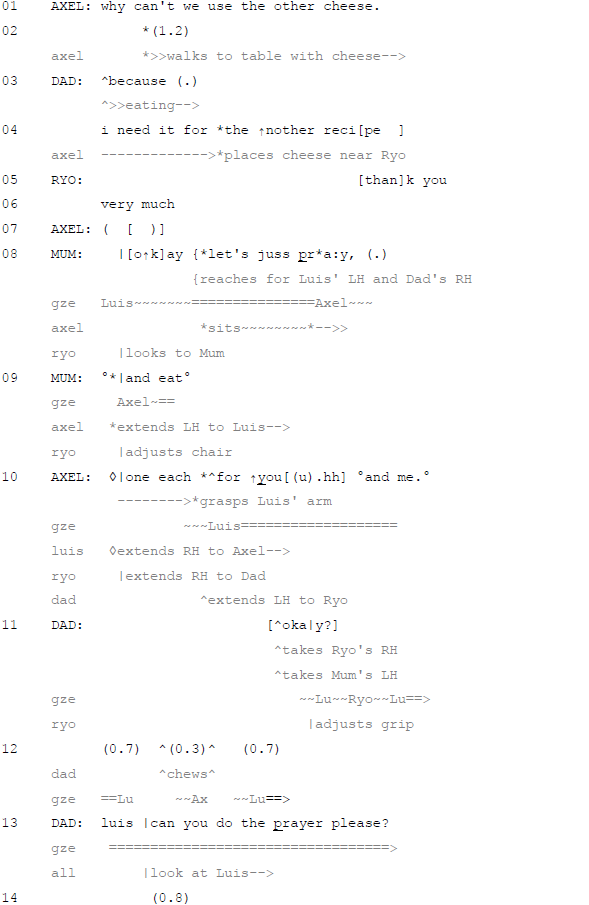

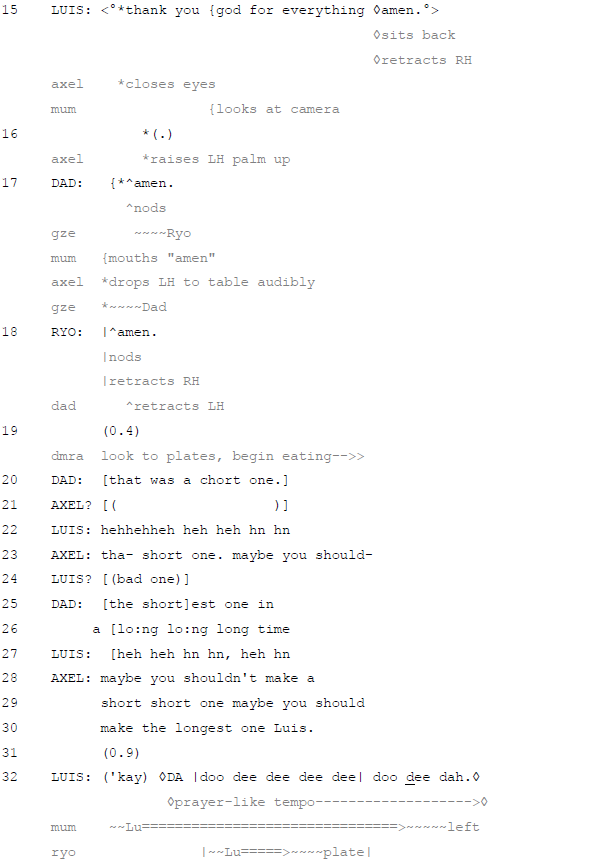

Excerpt 3. T3, 4 March

Axel has been off-camera looking for cheese in the refrigerator.

This episode begins in a sequential context in which the older son, Axel, has delayed the start of the meal by more than 5 minutes while searching for cheese in the kitchen. Lines 1-7 are part of that sequence, and Mum overlaps her turn in line 8, “Okay let’s just pray,” with Alex's talk in line 7, using the start of one activity to cut off another and orienting to the discussion between Axel and Dad as preventing the rest of the family from eating. Note at this point that although the family have been picking at their food, Ryo has not started eating, perhaps demonstrating his attention to the family’s meal rituals.

In this case, Dad selects Luis to say the grace (line 13), possibly because he is the only family member who has not been involved in the protracted discussion prior to this.[2] However, as we have seen, Luis is a relative novice to the practices of saying grace as well, if not in terms of language then certainly in terms of maturity. His six-year old version of the grace is very brief, as the other family members are quick to point out in the ongoing talk. Luis says only “Thank you God for everything amen” (line 15), formulating it intonationally as one sentence.

In line 20, Dad follows this with an assessment of the grace that is hearable as minimally critical. While Luis treats it as laughable in line 22, Axel goes on to formulate the criticism more directly, saying “maybe you shouldn’t make a short short one, maybe you should make the longest one Luis” (lines 28-30). Luis again treats this as only a mild rebuke, producing a second version of his grace in line 32 that maintains the intonation and tempo of a prayer without having any real content. While this is undoubtedly non-serious language play on the part of the family, some important lessons are available to Ryo as a peripheral observer of this interaction. First, the grace can be performed in different ways and with different words, although there are core elements to it—such as thanking God and finishing with Amen. Second, a grace that is too short can be seen as worthy of negative assessment. Finally, the prayer has a certain chant-like tempo that sets it apart from the surrounding talk. All these things come into play in the final clip in which Ryo himself is asked to give the prayer.

4.4 Ryo's formulation of the prayer

In the fourth and final clip, taken in the third week, Dad is not present, and Mum asks Ryo to say the prayer. In an interview with the author afterwards, Ryo confirmed this was the first time in his life he had ever said grace, so it is worth investigating how he formulates it and comparing it to the way Dad said the prayer in the earlier excerpts.

Video 4. T4, 10 March

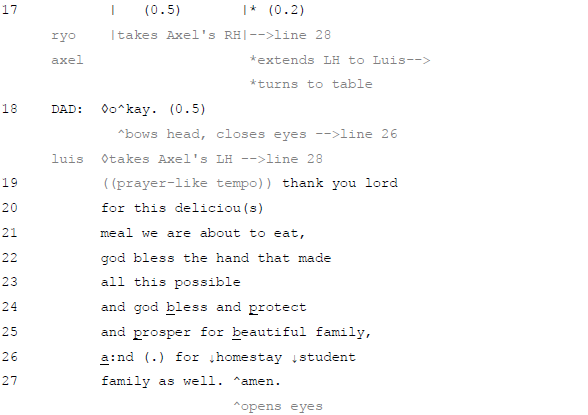

Excerpt 4. T4, 10 March

Dad is not present.

As Ryo walks to the table, Mum selects him to say the prayer in line 7 with the embodied completion request “can you do the” and a nod that serves as a multimodal completion (Mondada, 2015; Persson, 2017). By acquiescing in a timely fashion with “okay” (line 5), Ryo demonstrates (a) that he understands what Mum meant by her incomplete request and (b) that he has rightly projected the occurrence of grace in this sequential slot. He then launches into what is hearable as a secular version of the prayer: Between lines 9 and 12, he says, “Thank you very much for the great food and for this family, amen.” Note that this covers the key points that Dad’s prayer covers—food and family—but without specifically mentioning God. Moreover, as a peripheral witness to Luis’ version of grace (Excerpt 3), Ryo is aware that the grace does not have to be in the exact words as Dad’s and that even a novice version will be accepted. In fact, we see the family supporting Ryo with Axel providing candidate other-repair in line 11 and Mum giving a post-prayer positive assessment that works as a compliment in line 13.

4.5 Learning to hold hands: embodied readiness

As noted above, one key physical posture that distinguishes the prayer from surrounding talk is the fact that the family joins hands. This is no doubt a cultural practice to which is Ryo unaccustomed since holding hands at the table is unusual in Japan, even among family members. This section will explore the development of Ryo’s interactional competence across the four excerpts by focusing on Ryo's embodied action as the family joins hands at the start of each grace.

Figure 2. The family holds hands in the first recording

In T1, Ryo is spooning rice onto his plate when Dad prompts the group that the prayer is about to start by saying okay while looking at Ryo in particular. Dad takes Mum’s hand, and Mum reaches for Ryo’s. His right hand hovers momentarily above Mum’s hand before he takes it. At the same time, he looks to the other side of the table, first seemingly reaching for Juan’s hand, then retracting it and taking Gran’s, who is seated immediately to his left. In short, on this first occasion, it seems that Ryo is somewhat hesitant about the timing of joining hands for the mealtime prayer.

Figure 3. The family holds hands for grace in the second recording

In the second clip (Figure 3), when Dad initiates the grace by reaching out his hand and saying “Should we start with the prayer?” (Excerpt 2, line 10), Ryo first looks briefly at Mum and Dad’s joined hands then immediately takes Dad’s other hand.

Figure 4. The family holds hands for grace in the third recording

In the third clip (Figure 4), taken at the end of Ryo’s second week living with the family, Dad is eating and talking with Axel when Mum initiates the grace fairly abruptly with “Let’s just pray” (Excerpt 3, line 8), and this time Ryo holds out his hand to Dad, who is still eating, suggesting that he is able to predict and even initiate the interactional routines for beginning the meal. Note also that Ryo has not started eating at this point, unlike in the first excerpt.

Figure 5. The family holds hands for grace in the final recording

Finally, in the last clip (Figure 5), Ryo sits down and reaches out his hand to Mum even before she selects him to say the prayer. In short, a comparison of these four instances of embodied action suggest that Ryo has become accustomed to the practice of holding hands over the three-week homestay and is eventually able to adopt this physical stance at the appropriate point in the interaction, suggesting that he can project the onset of the prayer. This in itself provides evidence of the development of a micro-interactional competence constituent to this particular speech event.

5 Concluding discussion

Studying abroad brings opportunities for learning that go beyond just language and enter the realm of interculturality. This paper has used longitudinal conversation analysis to track the focal participant's increasing involvement in the family ritual of praying before each meal. Through a detailed turn-by-turn account of the interaction, the analysis demonstrates how the homestay student moves from peripheral observer toward a more active participant role, suggesting that his involvement in learning to say grace was one way in which he adapted his own cultural practices to align with those of the host family. As a form of opening sequence, we witnessed how Ryo became progressively more proficient at projecting the onset and completion of the grace and was able to time his participation accordingly. When he was called upon to lead the grace, he incorporated key features of the wording into a secular version of his own. At a micro-level, we can therefore see his development as part of a suite of multimodal and interactional competences—turn taking, word choice, hand-holding, co-completion—that combine to display his expanding participation in this speech event and the increased intercultural competence that accompanies it. Although this stance is reminiscent of Lave and Wenger's Communities of Practice (1991), that model was not intended as a starting point for the current study, and no attempt has been made to generalise the findings beyond the available data set. Instead, I have aimed to demonstrate how learning on the periphery occurs in the here-and-now of actual conversations (Larson, 1996; Okada, 2010).

However, this development is not due to Ryo's efforts alone. One of the major differences between interactional competence and Hyme's notion of communicative competence (Hymes, 1972) is that the former is seen as co-constructed by all the participants, rather than as residing in the learner alone (Young & Miller, 2004). Over the three weeks of Ryo's homestay visit, the family members were also adjusting their understanding of his communicative proficiency and adapting their own interactional practices, as exemplified in the series of meal openings in this paper. In his discussant comments in a panel at the Interactional Competences and Practices in a Second Language (ICOP-L2) conference in Switzerland, Eric Hauser (2017, p. 3) noted that we should see changes in interactional competence as “as a change in the resource participants draw on to co-construct themselves and one another as interactionally competent, change in the practices that they engage in as they participate, and, possibly, change in what is expected of a particular participant in order for his or her participation to be considered competent.” In the earlier meals, the family members displays their expectation that Ryo's participation in the prayer need only involve adopting an appropriately respectful mien, but by the third week Mum shows her expectation of Ryo’s ability to participate more actively by calling on him to deliver the prayer. In short, developing interactional competence is a concern for both novice language learners and the experts who host them.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded in part by JSPS Grant 24520619.

References

Blum‐Kulka, S. (2008). Language socialization and family dinnertime discourse. In P. Duff, & N. Hornberger, (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education (pp. 87–99). New York, NY: Springer.

Brouwer, C.E., & Wagner, J. (2004). Developmental issues in second language conversation. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 29–47. Doi: 10.1558/japl.v1i1.29

Capps, L., & Ochs, E. (2002). Cultivating prayer. In C. Ford, B. Fox, & S. Thompson (Eds.), The language of turn and sequence, (pp. 39–55). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Duranti, A., & Black, S. P. (2011). Language socialization and verbal improvisation. In A. Duranti, E. Ochs, & B. Shieffelin (Eds.). The handbook of language socialization, (pp. 443–463). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Greer, T. (2016). Learner initiative in action: post-expansion sequences in a novice ESL survey interview task. Linguistics and Education, 35, 78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.linged.2016.06.004

Greer, T. (2017). L1 speaker turn design and emergent familiarity in second language Japanese. In T. Greer, M. Ishida, & Y. Tateyama (Eds.), Interactional competence in Japanese as an additional language, (pp. 369–408). Honolulu, HI: National Foreign Language Resource Center.

Hall, J.K., & Pekarek Doehler, S.P. (Eds.). (2011). L2 interactional competence and development. In J. Hall, J. Hellermann, & S. Pekarek Doehler (Eds.), L2 interactional competence and development (pp. 1–15). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Hall, J.K., Hellermann, J., & Pekarek Doehler, S.P. (Eds.). (2011). L2 interactional competence and development. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Hauser, E. (2017). Dialectical conceptualizations

of interactional competence. Discussant remarks on a panel on Longitudinal

IC at the ICOP-L2 Conference at Neuchetal University, 17 January. https://www.academia.edu/31003878/Discussant_Remarks_Panel_on_

Longitudinal_IC_ICOP_L2_Conference_Neuchatel_Switzerland_January

_2017

Hellermann, J. (2007). The development of practices for action in classroom dyadic interaction: focus on task openings. The Modern Language Journal, 91(1), 83–96. Doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00503.x

Hymes, D. (1972). Models of the interaction of language and social life. In J.J. Gumperz & D. Hymes (Eds.), Directions in sociolinguistics: The ethnography of communication (pp. 35-71). New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Ishida, M. (2009). Development of interactional competence: changes in the use of ne in L2 Japanese during study abroad. In H.T. Nguyen & G. Kasper (Eds.), talk-in-interaction: Multilingual Perspectives (pp. 351–385). Honolulu, HI: National Foreign Language Resource Center.

Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Larson, J. (1996). The participations framework as a mediating tool in kindergarten journal writing activity. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 7(1), 135–151.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lee, Y.A., & Hellermann, J. (2014). Tracing developmental changes through conversation analysis: cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. TESOL Quarterly, 48(4), 763–788. doi: 10.1002/tesq.149

Markee, N. (2008). Toward a learning behavior tracking methodology for CA-for-SLA. Applied Linguistics, 29(3), 404–427.

Mondada, L. (2012). Video analysis and the temporality of inscriptions within social interaction: The case of architects at work. Qualitative Research, 12(3), 304–333.

Mondada, L. (2015). Multimodal completions. In A. Deppermann & S. Günthner (Eds.), Temporality in interaction. (pp. 267–307). Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Nguyen, H.T. (2012). Developing interactional competence: a conversation-analytic study of patient consultations in pharmacy. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Ochs, E., & Shohet, M. (2006). The cultural structuring of mealtime socialization. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 111, 35–49.

Okada, Y. (2010). Learning through peripheral participation in overheard/overseen talk in the language classroom. In T. Greer (Ed.), Observing talk: conversation analytic studies into second language interaction (pp. 133–149). Tokyo, Japan: JALT.

Schegloff, E.A. (2002). Opening sequencing. In J. Katz & M. Askhus (Eds.), Perpetual contact: Mobile communication, private talk, public performance, (pp. 326–385) Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Schegloff, E.A. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction: A primer in conversation analysis (Vol. 1). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Waring, H.Z. (2013). ‘How was your weekend?’: developing the interactional competence in managing routine inquiries. Language Awareness, 22(1), 1–16. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2011.644797

Young, R.F., & Miller, E.R. (2004). Learning as changing participation: discourse roles in ESL writing conferences. The Modern Language Journal, 88(4), 519–535. doi: 10.1111/j.0026-7902.2004.t01-16-.x