2018 VOL. 1, Issue 1

ISSN: 2446-3620

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7146/si.v1i1.105497

Social Interaction

Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality

CONFIGURING MATERIALITY, MOBILITY, AND MULTIACTIVITY: INTERACTIONS WITH OBJECTS IN CARS

Maurice Nevile[a]

Department of Design and Communication, University of Southern Denmark

Abstract

This paper explores how material objects feature within social interaction in the car. Objects in the car commonly include phones or other technologies, food, bags and carry items, body care products, written materials, clothing, and toys. The paper considers two examples to show how participants’ interaction with objects can be occasioned and conducted. In the first, driver spontaneously initiates involvement with the object to materially support an already-developing course of social activity (singing to passenger). In the second, driver prepares an object as a new focus of social activity with passenger (an envelope containing photos and a thank-you card). In both cases, we see especially how driver and passenger, as both vehicle occupants and social participants, organise the demands of attending to and handling objects with the dynamic demands of driving, and relative to the car’s movement in the external environment. We see how driver, in particular, embodiedly orients to objects (gaze, handling) so that driving is treated as the primary activity in a multiactivity setting. This study therefore highlights interaction in cars as a site for configuring materiality, mobility, and multiactivity. Data examples are from a corpus (27 hours, 90 journeys) of video recordings of ordinary car journeys in Australia. The language is English.

Keywords: cars, driving, materiality, mobility, multiactivity, objects, participation

1. Introduction

This paper examines how material objects feature in social interaction in cars, using as data video recordings from ordinary journeys. By considering two examples in detail it highlights how participants (driver and passenger) occasion and organise their involvement with objects, especially relative to the demands of driving and the circumstances of the mobile driving environment. The first example shows how an object (drink bottle) features spontaneously and contributes to a social action already underway; the second example shows how an object (envelope with papers inside) is prepared and then features as itself the focus for social activity.

The car’s role beyond mere transport, as a site for personal, social, and work life is typically considered by sociologists and social geographers, especially within studies of automobility and mobility(ies) (e.g. Featherstone, Nigel, & Urry, 2005; Cohen, 2006; Hagman, 2006; Huijbens & Benediktsson, 2007; Redshaw, 2008; Ferguson, 2009). These mostly draw upon surveys, interviews, or statistical or other documentary records or provide ethnographic, conceptual, historical, or theoretical discussions. They are predominantly concerned with noting the car’s significance, role, and impact for groups, locations, populations, or purposes and in and for wider societal and cultural constitution and change.

However, when we go inside the car and video record drivers’ and passengers’ conduct during ordinary, naturally occurring journeys, we can see precisely how they create cars as sites of social life, in situ and moment-to-moment. Drivers use cars to get from A to B, but they also often share the drive with others, and as social participants, drivers and passengers interact to, for example, manoeuvre and navigate to their destination, conduct personal and social activities (e.g. as family, friends, colleagues), or get work done (see collection Haddington, Keisanen, & Nevile, 2012; and earlier e.g. Laurier, 2004, 2005). Interaction also enables teaching/learning driving itself (De Stefani & Gazin, 2014). Social interaction occurs either for driving, serving the driving activity and its goals, or with driving, merely featuring alongside the driving activity (Nevile, 2012, p. 173). Participants interact relative to practices of driving and the car’s movement within external physical surroundings, so realising “the intertwining of multiple modalities of language, the body, and artefacts of the material world of the car” (Haddington, Nevile, & Keisanen, 2012: p. 102).

We see too that cars are usually populated with material objects like food and drink, bags (handbags, briefcases, shopping), technical devices (phones, tablets), clothing and grooming items, toys, wallets and payment cards, and printed matter (books, envelopes, maps etc.). Some objects might be there temporarily, brought along for the journey, but others are present more or less permanently, cluttering seats, floors, storage places, or any available space. So, this paper furthers studies of interaction in cars by focussing on the sociality of objects, how they come to feature in interaction between driver and passenger. Examples show how and when objects can come to be talked about, gazed at, touched and handled, passed from person to person, retrieved and placed, and how participants conduct and organise the demands of attending to and handling objects with the demands of driving in a mobile environment.

The paper builds directly on three areas of rising research interest in conversation analysis studies of social interaction, evidenced by recent collections.

1.1 Materiality/objects (see Nevile, et al., 2014a): Objects feature within and can shape courses of social activity, for example, as used, touched, handled, perceived, understood, appreciated, requested, shared, categorised, selected, instructed or learned, planned, created or transformed, invoked or imagined—or otherwise as relevant for whatever social action is underway. Nevile et al. (2014b) distinguish between two potentials for objects-in-interaction, as either practical accomplishments, emerging as the outcome of processes of interaction, or as situated resources, somehow involved in and even enabling whatever it is participants are doing.

1.2. Mobility (see Haddington, et al., 2013): Participants can interact when on the move from one location to another, for example simply by walking, or by using a mode of transport such as riding a bike, onboard an aircraft or maritime vessel, or on the road in a bus, or commonly, as here, in a car. In diverse ways, participants’ actions orient to the demands or opportunities of mobility and to the dynamic surrounding environment, perhaps to coordinate nature or direction of movement, to notice or act on something, or even to accomplish mobility itself. Mobility might also be subject to certain constraints. Here we see that the car seats driver and passenger side-by-side, facing forwards in the direction of travel (cf. the airline cockpit, Nevile, 2004, 2010; car passengers can also be behind the driver), and driving is subject to road boundaries and markings; controls such as traffic lights, signage, and formal rules-of-the-road; and the conduct of other traffic.

1.3. Multiactivity (see Haddington, et al., 2014): Participants in social interaction can make relevant and undertake two or more concurrent activities—in short, do more than one thing at a time. Participants orient to and coordinate the timing, order, and performance of multiple activities, for example, in parallel shifting from one to the other or by suspending and later resuming one activity. This paper extends interest in the car as a multiactivity setting (Mondada, 2012; Nevile, 2012) by examining interaction beyond talk and gesture to include material objects (see Nevile & Haddington, 2010).

Investigations relative to these three areas reflect a growing appreciation (Nevile, 2015) of social interaction’s order and accomplishment as inherently embodied, situated, and realised within the characteristics and circumstances of the physical surrounding environment (especially after C. Goodwin, 1981).

2. Data

Data are video recordings of drivers and passengers during ordinary, real-world journeys, collected in Australia for a study of in-car distractions and their impact on driving activities (Nevile & Haddington, 2010). The language is English. The full data set is approximately 27 hours of video recordings, representing 90 journeys varying in length from 4 and half minutes to over an hour. Most journeys were conducted within city and suburban confines, with a couple to neighbouring towns and one intercity trip. Cameras were mounted and operated by participants, under instruction from researchers, and captured the driver’s actions and usually also the actions of the front seat passenger as well as some details of the external environment. All journeys had a front-mounted camera (i.e. facing occupants), and 15 also had a rear-mounted camera (i.e. behind occupants). Both examples feature a driver and a front seat passenger, and in both cases the participants are a couple. Note that in Australia the traffic drives to the left, so driver sits to the right.

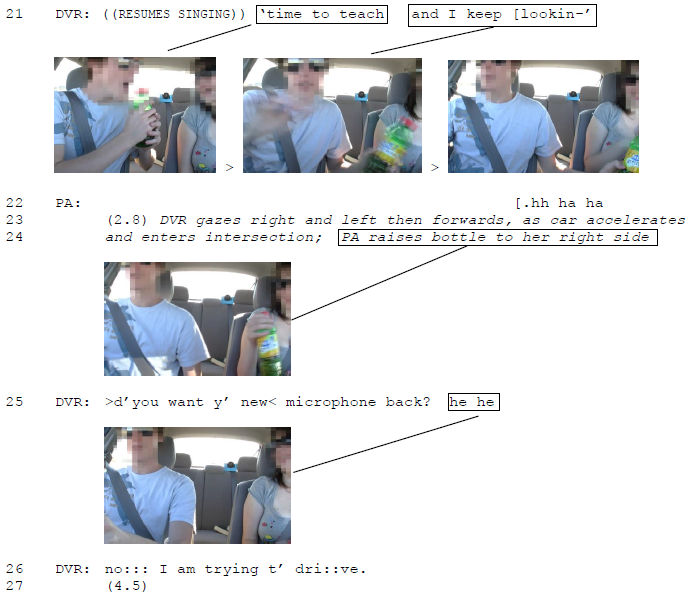

The transcriptions use two ways to indicate embodied conduct and its timing relative to emerging talk: 1) with italics and forward slashes (/, //); 2) with video stills and highlight boxes (participants’ faces have been anonymised). Details of the driving situation are in small caps, for example to show that the car slows for a red light. The second example first presents a timeline to indicate only embodied conduct.

3. Analyses: Object opportunities in the car

3.1 Example 1. Spontaneous object opportunity: Driver sings with bottle microphone

In the first example, driver (DVR) spontaneously appropriates a drink bottle as a microphone, with which he ‘serenades’ the front seat passenger (PA), his girlfriend, to music playing on the car’s entertainment system. As the excerpt begins, the car is stopped at a red traffic light. A previous topic of conversation has ended, and after a few seconds of silence, PA comments on the music with “it’s really like dancing” (line 02), “you could dance to this.” (line 04). DVR treats this literally, by beginning to tap on the steering wheel, moving his upper body to the music, and then singing along while turning his head towards PA. She treats this as a form of serenade, “is tha- (.) is that you serenading me?” (lines 11-12) and offers a challenge for him to do ‘better’ (line 15, “>can y’< give it a better attempt.”). As his response, DVR grasps a plastic bottle and sings into it. The example ends as DVR relinquishes the ‘microphone’ to the PA as the traffic light changes to green, and he must again drive. I will look first at how the bottle-as-microphone is relevantly and socially occasioned, and then consider how it is handled relative to the emerging demands of driving.

Extract 1a.

As he sings along to the music, DVR alternates his gaze between PA and forwards to the road and traffic, maintaining an ongoing orientation to the need to react when the light changes to green. When PA makes her challenge for DVR to make a ‘better attempt’ at his ‘serenade’, DVR responds by resuming singing, turning his head and gaze towards PA and clasping his hands together to simulate a microphone (line 18). Almost immediately, he reaches for a plastic drink bottle stored at the central console and lifts it to his face to replace his hands-only ‘microphone’ with a material one (line 18). He treats the bottle as physically and visually more equivalent to an actual microphone, in that he can hold and sing with it. So, DVR opportunistically transforms the bottle, as an available physical object, from its intended and usual function for drinking to something relevant for a specific social action in the moment—a microphone—to ‘better’ perform his serenade (see e.g. Streeck, 1996). As an actual simulated object, the bottle is an upgrade from merely clasping hands together as if holding a simulated object. However, DVR retains an orientation to driving. At the end of phrasing for a line in the song, and as PA laughs (line 20), DVR stops singing and holds the bottle in his right hand while with his left he manipulates the gear stick (apparently, we soon see, to engage first gear).

Most generally, we see how PA and DVR treat the break in demands of driving, being now stopped at a traffic light, as allowing them to engage in social activity involving resources beyond talk. They gaze towards each other, and DVR removes both hands from the wheel, orients his upper body left, and finds and handles a material object to ‘serenade’ his partner. In short, in the car DVR and PA are not just occupants, sharing a journey, but with a bottle-as-microphone they share an activity as a couple within the car’s confines of seatbelts and side-by-side seating.

Extract 1b.

Having manipulated the gear stick, DVR resumes singing with his bottle microphone, again holding it in both hands, and turns to face PA. However, he stops singing when he notices a change in the surrounding environment, likely traffic moving off as evidence of the light changing to green, and he quickly reorients his body and gaze to fully forwards, while simultaneously seeking to relinquish the bottle by holding it in front of PA, as an offer, who then accepts it.So both DVR and PA treat the bottle as incompatible with the demand to resume driving, allowing DVR to use both hands for the gear stick and to control the steering wheel. The once-microphone is again merely a bottle, and the impromptu serenade is over. DVR looks right and left to check for traffic as the car accelerates into the intersection, and although PA offers to return the microphone (line 25, “d’you want y’ new< microphone back?”), she presents this as non-serious by laughing and lowering the bottle to her lap before DVR can respond (lines 25-26). His response makes salient the bottle as now inappropriate, and his own role and accountability as driver, with “no::: I am trying t’ dri::ve.” (line 26).

3.2 Example 2. Prepared object: Driver shares photos and a card

The second example is longer, and we see a different couple, driving home at the end of a working day. Again, the one passenger is seated in the front. The object’s involvement is not occasioned spontaneously within a developing course of interaction. Instead, DVR prepares access to the object in advance so that she can present it as a focus of social activity. The object is an envelope containing two photos and a thank-you card and is not readily available to her in the driving seat. While PA tells a story about his working day, DVR retrieves the envelope from a carry bag, which she locates at the rear of the car, and places it in her lap. Presented first is a summary timeline highlighting her preparatory embodied conduct, covering 25 seconds. Then follows a transcription of interaction as DVR introduces and shares the envelope’s contents with PA. She handles, shows, and passes the written items, and repeatedly gazes to monitor PA’s responses while primarily directing her gaze forwards to monitor the road and traffic ahead (note: PA is the author and is wearing sunglasses).

DVR accesses an envelope in preparation for sharing: Summary timeline (showing elapsed time in seconds)