1

Introduction

Requests and

offers have generally been treated quite separately, as constituting

independent and distinct actions, each with its own morphosyntactic

construction, sequential and interactional environments, habitus, and

conditions as a speech act (e.g. Searle, 1969; and for a critical review of

such conditions, Drew & Couper-Kuhlen, 2014). For instance, a distinction is

often made between them in terms of benefactives, with the speaker being

regarded as the principal beneficiary of a request whilst the recipient is

considered the beneficiary of an offer (Clayman & Heritage, 2014; Couper-Kuhlen,

2014). However, our initial explorations of the claim that requests are

preferred over offers (Kendrick & Drew, 2014) have resulted in our

beginning to conceptualise these as connected symbiotically as alternative

methods for the recruitment of assistance (Kendrick & Drew, 2016).

When someone experiences difficulty, for instance in opening the lid of a jar,

they may ask for another’s assistance – they may request it verbally or may

simply pass the jar to someone standing nearby. It may happen that the person

nearby does not wait to be asked but instead verbally offers to open the lid or

perhaps simply stretches out their arm to take the jar to open the lid (i.e.

without making a verbal offer).

In some situations, someone may anticipate that another person is about to

encounter difficulty: They may be on the verge of running into trouble, so that

assistance is rendered in such a way that the difficulty is averted. The recruitment

of assistance embraces the variety of embodied forms of conduct through which assistance

may be solicited or provided, through verbal, vocal, and non-verbal conduct, to

resolve difficulties that are experienced, manifest, or anticipated, which

disrupt the progressive realisation of practical (embodied) courses of action.

It is evident that recruitment of another’s assistance requires us to broaden

our analysis to understand how a wider range of linguistic and semiotic

resources are deployed and engaged – together with gesture, bodily movement,

gaze, and so forth – in a physical setting. This requires what we have

traditionally and colloquially termed ‘requesting’ and ‘offering’ (Drew &

Couper-Kuhlen, 2014; Floyd et al., 2014; Käkkäinen & Keisanen, 2012;

Keisanen & Rauniomaa, 2012; Rossi, 2014; Mondada & Sorjonen, 2016;

Stevanovic & Monzoni, 2016).

A fuller account of the theoretical importance of recruitment as underpinning

social cooperation and cohesion – in part through shared practices for

manifesting or expressing trouble, for recognising or anticipating that another

is experiencing or is likely to experience difficulty, and for soliciting or

providing assistance to remedy those troubles – is beyond the scope of this

report. So too is a consideration of how recognition or anticipation of

another’s difficulty and the provision of assistance to resolve this difficulty

are key forms of pro-social altruism (on anticipation, see Enfield, 2014). The

central matter in this report is the conduct through which a difficulty is made

manifest or expressed in such a way that another may recognise that assistance

might be needed. Here we amplify our initial observation that embodied displays

of trouble constitute a central method for the recruitment of assistance

(Kendrick & Drew, 2016) and examine one coherent set of such embodied

displays in detail: visibly searching the environment. When one person,

Self, displays that he or she is searching for something, Other may recognise

that Self’s conduct manifests a difficulty he or she has. It happens quite

regularly in interaction that participants display, through visibly searching,

that they are having trouble finding a symbol on the computer keyboard, finding

a teapot, finding their fork (at the dinner table), locating their piece on a

game board, or finding an object in the kitchen. In some respects, this is akin

to or parallels studies of the embodied practices involved when speakers search

for words (Goodwin & Goodwin, 1986; Hayashi, 2003).

In

this report, we explore, from a conversation analytic perspective, how

participants’ conduct manifests that they are having trouble finding something,

through their visibly searching for something. Our analytic focus is on how

‘searching’ is performed in such a manner as to be understood or recognised by

others as searching and thereby as manifesting difficulty e.g. finding or

locating something.

2

Looking vs. searching

Gaze direction

is a fundamental resource for action in interaction (see Rossano, 2013). To

begin with, for our purposes, it is worth distinguishing between, on the one

hand, someone’s look across a space (a look followed by another look towards

its possible or likely object) and, on the other hand, Self’s conduct, which is

understood as looking for something, as searching for something that

Self is having difficulty finding (for a different though related treatment of

the relevance of gaze and the affordances for recruitment of sight lines in an

environment, see Backhouse & Drew, 1992). In other words, among the various

gazing actions that participants perform (see e.g. Kidwell, 2005 on ‘mere look’

vs. ‘the look’), there is a difference between looking and visibly searching. Whereas

looking does not seem to indicate or manifest trouble, the embodied conduct

associated with searching exposes to public view that Self is having trouble

locating something.

For

instance, in this first example in which three women are sitting together, the woman

in the middle – Self (Marie) – looks across and downwards to her right. She

does so in a slightly delayed response to having been asked by her friend on the

right, Rachel, do you have to leave soo:n (.) for a cla:ss? The friend

sitting on the left, Lex, then follows Self’s gaze down towards an object on

the floor close to her (i.e. to Lex), which turns out to be a cell phone. Lex

checks the time then displays or passes the phone to Self in such a way that

she can see the time for herself. The recruitment of assistance resulted from Lex

having followed the direction of Self’s gaze and discerned what Self was looking

at even though that look did not indicate any particular trouble or difficulty

on Self’s part. Lex simply anticipated Self’s need to know the time, in order

perhaps to be able to answer Rachel’s question about when she has to leave.

Extract 1.

[GB07_76]

It should be

noted with respect to Self’s glance having occasioned a recruitment that,

whilst the look did not signal or express trouble, there are nonetheless

intimations of something akin to a difficulty in Self’s conduct. First, as

noted above, Self does not respond immediately to Rachel’s question. At the

first possible completion of the question, Self averts her gaze (line 2), which

projects a dispreferred response and occasions an increment by Rachel (cf. Kendrick

& Holler, 2017). Self then utters a click (Ogden, 2013) and says “u::hm” (line

6), both of which are further indications of trouble in responding (Kendrick &

Torreira, 2015), as she turns her head to gaze towards the ground to her right.

Note also that Self looks across at something she knows or anticipates will be

in that location; the certitude embodied in her look contributes to the

recruitment of assistance from Lex.

In

other cases though, Self does much more than look. In Extract 2, Self (Anne)

visibly searches for an object, through first peering over her computer, in

what is evidently a search for something she cannot see or find.

Extract 2.

[RCE14

00:00]

Whilst Self’s

searching is embodied primarily in her head movements and associated gaze,

these are accompanied by her enquiry about the tea stewing (line 4), which

follows a first full scan of her immediate environment, presumably to find the

teapot. During the focal phase of her action, Other looks to his right, away

from Self. Self asks ‘s the tea been stewing long enough?,

then reaches for her mug. So whilst her enquiry does not directly indicate that

the teapot is not visible to her, it nonetheless serves to account for her

visible bodily action, specifying ‘teapot’ as the object of her search.

It is

evident that Self does more than glance or look; she embodies and thereby enacts

looking. Through her head movements, she displays that she is searching for

something. This is also evident in the next example, in which Self (Kelsey),

the one right of centre with her back to the camera, displays that she is

searching for something on the dinner table.

Extract 3

[LSIA

Never 52:26]

In contrast to

the previous example, Self’s visible search alone effectively recruits Other to

offer assistance (what’d you need at line 18). A visible search of the

environment thus creates a systematic opportunity for Other(s) to give or offer

assistance even though it does not guarantee this outcome. We continue our

analysis of this example in the next section.

3

Recognisability of searching

We have

described searching as embodying and thereby enacting and displaying ‘looking

for something’ that Self has trouble locating. The embodied conduct through

which Self implements a search is precisely what enables Other to recognise

that Self is having trouble, in response to which Other may be recruited to help

resolve the trouble, that of locating whatever it is for which Self is

searching. What, then, are the physical properties of Self’s conduct that

enable it to be recognised or understood as ‘doing searching’? In this section,

we document a set of practices that Self employs in visibly searching. We have

arranged these bodily practices in terms of those involving the head + neck, those in which the arms + hands (manual search) are the

primary ‘perceptors’, and those involving the body

+ torso (adjusting body position) as well as whole body movements such

as walking. Although we focus on each of these embodied ‘zones’ of conduct

separately, we often or even generally find that more than one zone is involved

in any given example. That is, whilst we may focus on head movements in one

example, hand gestures (second zone) may also contribute to the enactment of

searching. Actual cases thus involve complex multimodal gestalts (Mondada, 2014a)

in which multiple articulators across a range of embodied zones are combined in

displays of searching for what Self is having trouble finding. The various embodied

practices that enact visibly searching do not constitute different types of searches

per se but instead reflect local contingencies of the physical

environment in which the search takes place, Self’s position within that

environment, and the nature of the object being sought (e.g. its size or

visibility). The examples given below have been selected to foreground

particular practices of embodied action associated with particular zones of the

body that contribute to the recognisability of searching.

3.1 Searching through head and neck

movements

3.1.1 Visual sweep

Returning to Extract

3, we can see that Self begins her search when she extends her right arm,

seeming to reach for something. She then raises her arm so that her hand

remains stationary for an instant. The suspension of an embodied action, which

halts its progressive realisation, can itself indicate trouble (Lerner &

Raymond, in press). Self glances briefly to her right, then over to her left, retracts

her hand/arm, then whilst rubbing her hands together turns her head more

distinctly from (her) left to right – thereby performing a visual sweep across

a portion of the table in front of her. She reaches with her left hand to

slightly lift a packet that is just in front of her. As she lifts the packet,

she leans to her left in such a way that her head is positioned so as to enable

her to peer under the packet.

The trouble

she is evidently having in finding whatever she is looking for, as manifest in

her sweep and peering, is recognised by Other (facing camera, wearing a stripy

top), who asks what do you need?, which is the first step in the

recruitment of Other’s assistance, which resolves Self’s difficulty.

This

visual sweep in Extract 3, also evident in Extracts 6 and 7 below, is common in

our data and is sometimes accompanied by a ‘thinking face’ (see Kendrick &

Drew, 2016: 12, Goodwin & Goodwin, 1986). However, the visual sweep is only

one aspect of Self’s conduct that results in recruitment of Other’s assistance;

another aspect of Self’s conduct is that she leans forward and to her left,

thereby (literally) closing in on – or ‘zooming’ in on – whatever she might be

looking for. We explore zooming in the next section.

3.1.2 Zoom

In some of our

cases, Self zooms in on a quite restricted search domain, a specific

domain of scrutiny (Goodwin, 1994), thereby reducing the distance between the

sense organ (eyes) and the objects in the environment. This occurs in the next

example.

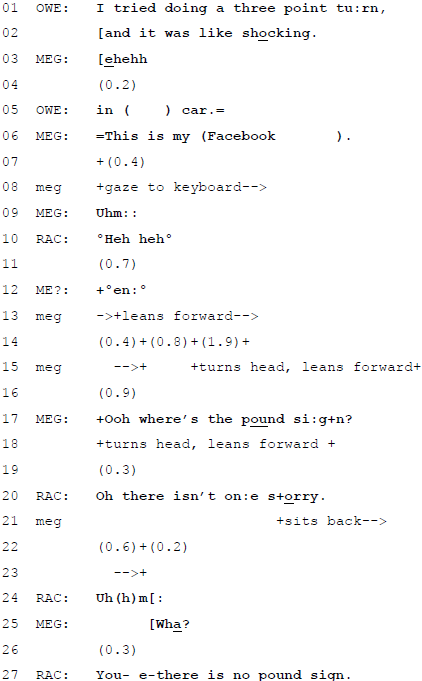

Extract 4.

[RCE22b

10:28]

The woman in

the back left of the frame, Self (Megan), is using a laptop belonging to her

Canadian friend, the woman sitting next to her. Self is evidently looking for

but cannot find the British pound sign (£) on the keyboard. Before she verbally

articulates her difficulty finding this symbol, she leans in slightly towards

the computer, then does the slightest (her) right-left visual sweep, following

which she leans forward and extends her head even closer and downwards to peer

at the keyboard, saying as she does so ooh where’s the pound si:gn?,

in so doing specifying the source of her difficulty. The relevant visual domain

is restricted to the keyboard, for which the zoom – produced by the forward

extension of the head together with the lean – is the most effective visual

means of displaying Self’s difficulty, though that difficulty is also expressed

by her “uhm:” in line 9 and the suspension of her turn. This difficulty is

resolved when Other, to whom the laptop belongs, explains that it does not have

a pound sign (because it is a North American laptop).

3.2 Searching through arm and hand

movements

3.2.1 Searching gestures

The next

bodily ‘zone’ employed in search displays or enactments is the hands and thus

necessarily also the arms. We saw in Extract 3 that Self reached out across the

table at the beginning of her search, then at a later stage stretched out her

other arm, using her hand to lift the packet sufficiently for her to peer under

it. Stretching out an arm and displaying ‘searching’ through the use of the

hand/digits is particularly visible in this next example. In this excerpt, the participants

are playing a board game (Monopoly), and Self (Nick), the man to the left of

the screen, has just thrown the dice. Self searches for his piece so that he

can move it a certain number of spaces forwards along the board.

Extract 5.

[GB07-2]

Self stretches

his arm out diagonally to the right, as though to alight on his piece, which

evidently is not at the location to which his hand moves. Instead his hand

hovers over the area on the far right of the board, and he wiggles his fingers

in a gesture of ‘searching’. The gesture indicates that a search is in progress

and thereby accounts for the disruption in the progressive realisation of his

course of action.

When

reaching for an object, one has that object in view (either in direct sight

line or metaphorically ‘in view’, such as when one reaches behind to take

something out of a bag, without looking where one is reaching). Here, however,

Self does not have the object in view when he reaches and thus encounters

trouble. His finger wiggling, accompanied by his visual search, render his

conduct visible as ‘searching for’ his piece in this restricted search domain,

i.e. the game board. It might be noted parenthetically that both of the Others

are recruited to assist, each by pointing at the ‘missing’ piece, though the

point from one Other, on the right, is a kind of ‘post recruitment’ (i.e.

recruitment of assistance after resolution of the trouble) since Self is

already holding his piece and has begun moving it by the time this Other

points.

3.2.2 Tactile sweep

In a final

example to illustrate how conduct involving arm/hand movement visibly enacts

searching, an Italian family is sitting down to dinner when the boy on the

right, Self, discovers that he does not have a fork with which to eat his food,

a difficulty that he announces in no uncertain terms. However, immediately

before he verbalises the trouble, the missing fork, he begins a visual sweep,

moving his head from left to right. As he does so, he holds his knife in his

right hand, whilst concurrently with the trouble report hei ma io non ce l’ho la forchetta ‘hey but I

don’t have the fork’ (line 3), he sweeps his right hand around and just under

the rim of his shallow dish, in a tactile search to determine whether the fork

might be hidden under/behind his bowl (line 4). As his hand sweeps around the

bowl, his gaze follows his hand movement.

Extract 6.

[9OAW_IT_10]

Self’s visual,

verbal, and embodied (manual) displays of searching for a fork that he cannot

find (the trouble) promptly occasion the recruitment of his mother sitting to

his right, who picks up a fork that was to the (right) side of her dish and

passes it to him (line 6).

3.3 Searching through torso and leg

movements

3.3.1 Leaning

In most of the

previous examples, it is evident that alongside visual sweeps and zooms, manual

sweeps and verbal reports of the trouble, Self quite regularly makes

adjustments to her/his corporeal deportment or body position. Generally, such

body movements bring Self closer to the presumed location or zone of the

sought-after object. For instance, compare the body position of the boy in the

previous example as he begins to say hei ‘hey’ with his position a

little over a second later as he passes his right hand around and under the rim

of his dish (figure 1).

Figure 1:

The boy leans forward as he begins his search in Extract 6.

In the second

still, he is clearly leaning forward, in contrast to his upright posture in the

first still. Similarly, in Extract 2, Self leans forward and to her right in

her recognisable search for the teapot.

Figure 2:

Anne leans forward as she searches for the teapot in Extract 2.

In Extract 3,

Self leans forward and to her left as she reaches out to move and look under the

packet on the table in her search for whatever she is looking for.

Figure 3:

Kelsey (third from left) leans forward and to her left as she searches the

table in Extract 3.

In each of

these and other examples, the participants are sitting down, to dinner, to play

a board game, at a table, or at desks discussing a presentation. Their body

movements are thereby restricted to leaning forwards or sideways as well as possible

body torques from the waist. They are, though, pretty much rooted to their

chairs or to whatever they are sitting on.

3.3.2 Exploring

Participants

in a natural environment, however, readily move around that environment. They

get up out of their seats to fetch something, they move around a kitchen whilst

cooking, they stand, walk about, and so on. Such body movements constitute

conduct providing some of the most vivid embodied displays of searching,

through participants exploring their environment in search of something

missing (searching for the trouble). Extract 7 illustrates the combined forms

of conduct through which someone may visually sweep and explore a space in such

a way as to be visibly, recognisably searching for something.

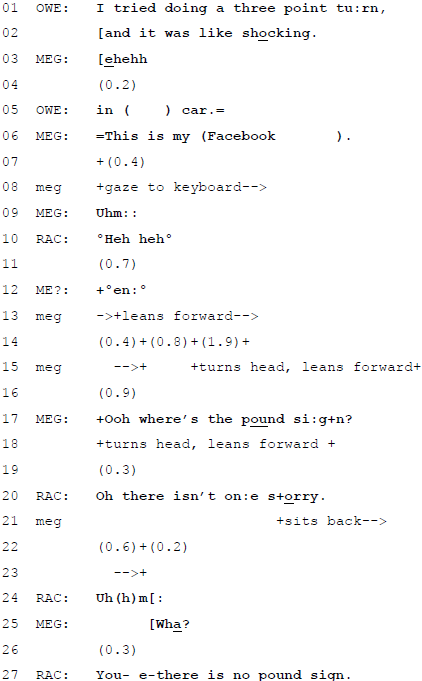

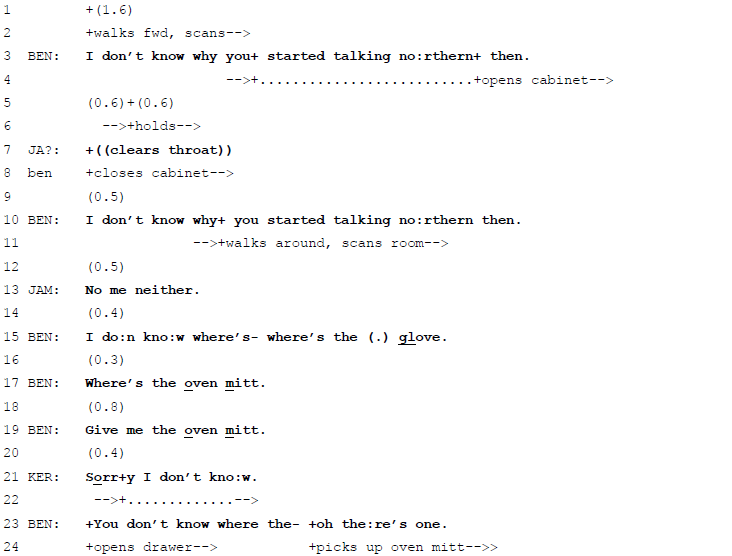

Extract 7.

[RCE09

13:34]

In this example,

Self (Ben), the man in a white shirt, who begins in the middle of this kitchen

scene, begins by walking across to a cupboard. He opens the cupboard door (line

4), looks inside, and evidently does not find whatever he might have been

looking for (i.e. he closes the door without having retrieved anything from the

cupboard at line 8). He then turns as though to move to his right but turns

again to his left, then back to his right, all whilst in a relatively stable

(standing) position. He then takes two steps forward, in the direction of the

sink, and as he finishes his second step asks, loudly, where’s the (.) glove

(0.3) where’s the oven mitt. (0.8) give me the oven mitt

(lines 15-19) – thereby nominating and requesting the object for which he is

searching. He moves to his left, and with knees slightly bent and a forwards-leaning

posture, opens a drawer from which he takes an oven mitt (line 24). The

recruitment is completed after Self has explored his environment (i.e. part of

the kitchen) in evident search for the oven mitts. Through his conduct (his

body movements and gaze, including looking into a cupboard), he enacts

searching for something.

4

Discussion

We have distinguished

between two kinds of gaze, looking and searching. When someone gazes

at something or in a certain direction, another person may understand that

person as looking at something. The Other may furthermore infer that

Self (the one gazing) is looking at something he or she needs for a course of

action to progress. A look in a certain direction conveys knowing that

something or someone is to be found in the direction of the gaze. By contrast,

when a participant visibly searches for something, they may be

recognised as having trouble knowing where something is, having trouble

finding something. On occasion, this trouble may be verbalised by Other in

response to Self’s glance, as in Extract 3 when Other asks what’do you need?.

Alternatively, the trouble may be verbalised by Self, as Ben does in Extract 7

when he accompanies his searching conduct with the request where’s the oven

mitt? Across the collection it is generally the embodied display of

trouble that precedes such verbalisations (cf. Kendrick & Drew, 2016). Recognising

Self’s difficulty, Other may assist in some way to resolve the difficulty, in

which case they are recruited to assist, and the course of action in which Self

is involved can move forward. At the heart of what we have investigated here is

that searching enacts having trouble finding what one is looking for and

thereby manifests trouble in an embodied display.

In

some respects, searching might be considered an exaggerated way of looking for

something (cf. Kendrick & Drew, 2016: 16). We have preferred instead to

describe this as enacting having trouble finding what one is looking for or as

a version of ‘doing looking for’ in which one is accountably, recognisably, or

visibly having difficulty finding something. In this study, we have identified

the practices in participants’ (Self’s) embodied conduct through which they

enact or display trouble. Through such conduct as visual sweeps, zooming,

tactile displays of searching, adjusting one’s body position to bring one

closer and hence reduce the search domain, and exploring the environment both

visually and through movement, Self manifests their difficulty in finding what

they are looking for. In this way searching is one of the key practices in the recruitment

of assistance.

Acknowledgments

We would like

to thank Galina Bolden, Renata Galatolo, and Erika Vassallo for their permission

to use specific examples in this report. We are also grateful to Leah Wingard

for the Language and Social Interaction Archive (2014), from which data have

been drawn for this research.

Conventions for

multimodal transcription

Embodied

actions are transcribed according to the following conventions, developed by

Mondada (2014b).

|

* *

+ +

|

Gestures and descriptions of embodied

actions are delimited between ++ two identical symbols (one symbol per

participant) and are synchronized with correspondent stretches of talk.

|

|

*--->

--->*

|

The action described continues across

subsequent lines until the same symbol is reached.

|

|

>>

|

The action described begins before

the excerpt’s beginning.

|

|

--->>

|

The action described continues after

the excerpt’s end.

|

|

.....

|

Action’s preparation.

|

|

,,,,,

|

Action’s retraction.

|

|

ali

|

Participant doing the embodied action

is identified when (s)he is not the speaker.

|

|

fig

#

|

The exact moment at which a screen

shot has been taken is indicated with a specific sign showing its position

within turn at talk.

|

References

Backhouse,

A., & Drew, P. (1992). The design implications of social interaction in a

workplace setting. Environment and Planning B, 19, 573-584.

Clayman,

S., & Heritage, J. (2014). Benefactors and beneficiaries: Benefactive

status and stance in the management of offers and requests. In P. Drew & E.

Couper-Kuhlen (Eds.) Requesting in social interaction (pp. 51-82). Amsterdam:

John Benjamins.

Couper-Kuhlen,

E. (2014). What does grammar tell us about action? Pragmatics, 24,

623-647.

Drew,

P., & Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2014). Requesting – from speech act to

recruitment. In P. Drew & E. Couper-Kuhlen (Eds.) Requesting in social

interaction (pp. 1-34). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Enfield,

N.J. (2014). Human agency and the infrastructure for requests. In P. Drew &

E. Couper-Kuhlen (Eds.) Requesting in social interaction (pp. 35-51).

Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Floyd,

S., Rossi, G., Enfield, N.J., Baranova, J., Blythe, J., Dingemanse, M.,

Kendrick, K.H., & Zinken, J. (2014). Recruitments across languages: A

systematic comparison. Presented at the 4th International Conference on

Conversation Analysis, University of California at Los Angeles, CA.

Goodwin,

C. (1994). Professional vision. American Anthropologist, 96(3), 606-633.

https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1994.96.3.02a00100

Goodwin,

M.H., & Goodwin, C. (1986). Gesture and coparticipation in the activity of

searching for a word. Semiotica, 62, 51-75.

Hayashi,

M. (2003). Language and the body as resources for collaborative action: A study

of word searches in Japanese conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction,

36, 109-141.

Kärkkäinen,

E., & Keisanen, T. (2012). Linguistic and embodied formats for making

(concrete) offers. Discourse Studies, 14(5), 587-611. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445612454069

Keisanen,

T., & Rauniomaa, M. (2012). The organization of participation and

contingency in prebeginnings of request sequences. Research on Language

& Social Interaction, 45(4), 323-351. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.724985

Kendrick,

K., & Drew, P. (2016) Recruitment: Offers, requests, and the organization

of assistance in interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction,

49, 1-19.

Kendrick,

K.H., & Holler, J. (2017). Gaze direction signals response preference in

conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 50(1), 12-32.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2017.1262120

Kendrick,

K.H., & Torreira, F. (2015). The timing and construction of preference: A quantitative

study. Discourse Processes, 52(4), 255-289. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2014.955997

Kendrick,

K., & Drew, P. (2014). The putative preference for offers over requests. In

P. Drew & E. Couper-Kuhlen (Eds.) Requesting in social interaction (pp.

87-114). Amsterdam: John Benjamins:.

Kidwell,

M. (2005). Gaze as social control: How very young children differentiate ‘the

look’ from a ‘mere look’ by their adult caregivers. Research on Language and

Social Interaction, 38(4), 417-449. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327973rlsi3804_2

Language

and Social Interaction Archive. (2014). Available from San Francisco State

University. http://www.sfsu.edu/~lsi/

Lerner,

G.H., & Raymond, G. (in press). Body trouble: Some sources of interactional

trouble and their embodied solution.

Mondada,

L. (2014a). The local constitution of multimodal resources for social

interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 65, 137-156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.04.004

Mondada,

L. (2014b). Conventions for multimodal transcription. Available from https://franz.unibas.ch/fileadmin/franz/user_upload/redaktion/Mondada_conv_

multimodality.pdf

Mondada,

L., & Sorjonen, M.L. (2016). Making multiple requests in French and Finnish convenience stores. Language

in Society, 45(5), 733-765. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404516000646

Ogden,

R. (2013) Clicks and percussives in English conversation. Journal of the

International Phonetics Association, 43, 299-320.

Rossano,

F. (2013). Gaze in conversation. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.) The handbook

of conversation analysis (pp. 308-329). Malden: Blackwell.

Rossi,

G. (2014). When do people not use language to make requests? In P. Drew &

E. Couper-Kuhlen (Eds.) Requesting in social interaction (pp. 303-334).

Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Searle,

J. (1969). Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Stevanovic,

M., & Monzoni, C. (2016). On the hierarchy of interactional resources:

Embodied and verbal behaviour in the management of joint activities with

material objects. Journal of Pragmatics, 103, 15-32.