Publiceret 15.12.2012

Citation/Eksport

Copyright (c) 2012 Tidsskriftet Kirkehistoriske Samlinger

Dette værk er under følgende licens Creative Commons Navngivelse – Ingen bearbejdelser (by-nd).

Resumé

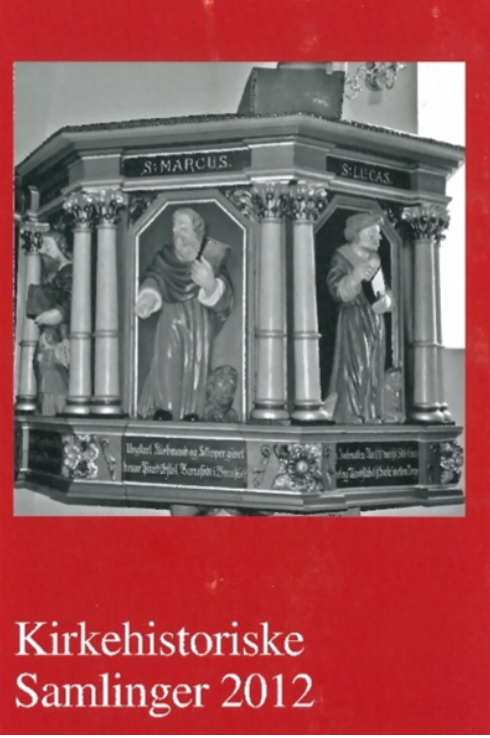

Epitafier er type af gravminde, der har sin storhedsperiode i mellem reformationen og slutningen af 1700-tallet. Tilsyneladende er epitafier ikke altid blot markeringer af grave eller skrevne lovtaler over de døde. Epitafier kan anskues som en del af en donationskultur, der kan manifestere sig på flere måder: enten ved at et kirkemøbel fremstilles med epitafiefunktion eller ved, at epitafier benyttes som en slags offentligt synlige, retsgyldige dokumenter. De kan henvise til eksistensen af stiftede gaver og ydelser. I den sidste del af epitafiets historie er det den ædle følelse, det almene sociale sindelag, der fremhæves. Epitafiets private karakter opløses til fordel for almennytten.

Summary

Deceased with deeds

About the ambiguous forms and functions of epitaphs

The article discusses the term and the concept epitaph in Denmark between Reformation and Enlightenment. An epitaph in its original form is a deed, a written or painted message stating that a grave has been paid for, and it is a warning not to dig into any existing tomb or vault. It seems that the nobility in some instances chose to combine epitaphs with pieces of ecclesiastical furniture. Thus altar tablets may have been donated to a church with the secondary purpose of marking the burial place of the donator himself. Pews, pulpits and even baptismal fonts donated by wealthy burghers of the 17th Century occasionally turn out to be markers of donations as well as and graves. How then to distinguish between votive tablets, epitaphs, and deeds? Memories for people dead at sea seem to pinpoint this problem. During the 18th Century it becomes customary to publish the deceased’s wills by means of huge inscriptions on tablets in the churches – or to refer to the existence of deeds existing in the chests or archives of the dioceses or magistrates. It has to be made obvious to anyone that money have been invested in order to maintain the donator’s graves until the second coming of Christ, or that capital has been invested for the needs of the families of the deceased or for the common good. As an example a huge tablet I Western Jutland states, that amounts of money have to be paid to people in need, and that Bibles and other books be brought to the poor at certain seasons of the year – not to forget money for the maintenance of the local fire station. So the purposes of epitaphs and of donator’s tablets in some instances seem to be similar. Both aim at memorizing the dead and setting a good example within the frames of the Lutheran concept of vocation. The Enlightenment however seems to have stressed the actual charity in the

wider society on account of the pursuit of eternal security and hope of the deceased donators themselves and the upholding of their noble but vain graves in the pretty local milieu. The epitaphs of the later 18th Century are more concerned with the common good.